The Arctic is a place that, for outsiders, is often perceived as an empty canvas on which one’s own ideas and imaginations can be painted. This is not only inaccurate as it disregards the lived reality of the people who live there, but it also can be dangerous if decisions were to be made on matters of safety and disaster risk reduction and response without taking into account the practical realities on the ground.

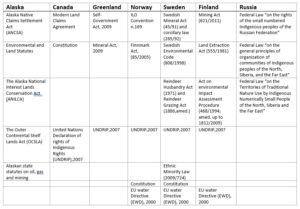

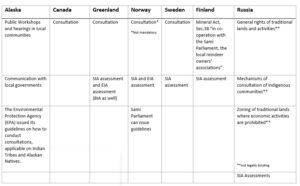

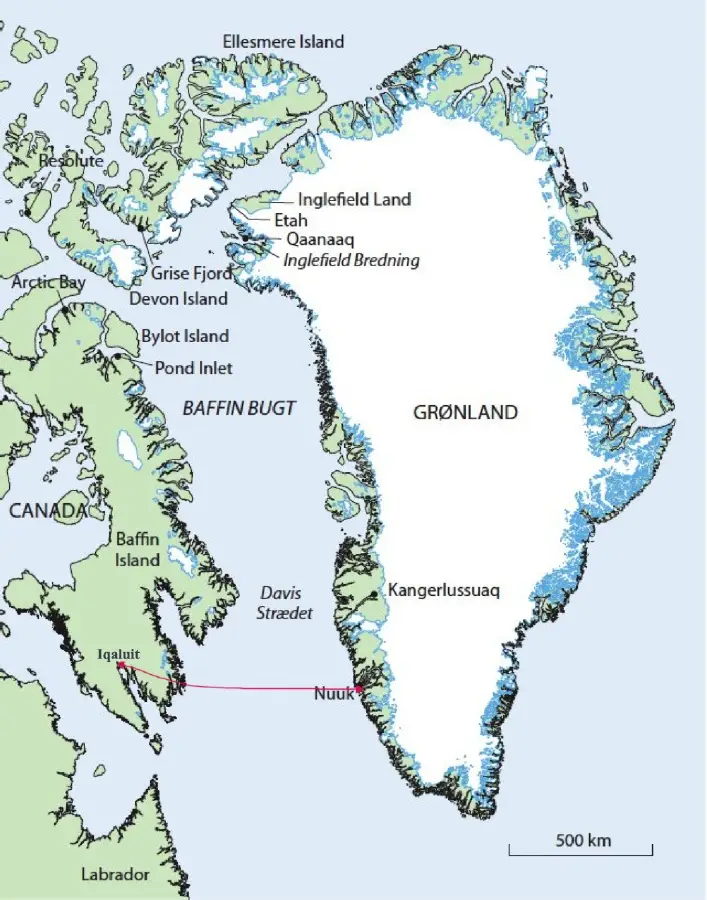

There is not one generally accepted definition of what constitutes the Arctic. For the purposes of this paper, the term “Arctic and Sub-Arctic” is used to describe the area that is comprised of the parts of the United States, Canada, Greenland, Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia that are located north of 60° N. In practice, the focus will be on the forested, taiga and tundra areas of the continental areas because the situation in Greenland, which had seen a wildfire in the far West in 2019,[1] and Iceland is rather different from the afore-mentioned regions.

From the outside, the Arctic and Sub-Arctic is often perceived as a rather cold and humid place, characterized by ice and water, lakes and marshes. The reality is, however, that many parts of the Arctic receive very little precipitation compared to e.g. central Europe (although precipitation in the Arctic is increasing significantly[2]), and such outside perceptions view can lead to underestimating the risk of wildfires in the region, when seen from the outside. Within the Arctic, though, the issue of wildfires has been a topic of increasing international concern for some time, notably at the Arctic Council. In recent years, the risk of wildfires has grown significantly: “Wildland fires across the Northern hemisphere have notably increased in frequency, severity and area across the Arctic over the past several years.”[3]

Due to climate change, thunderstorms and lightning strikes that used to be rare in the Arctic, have become more common,[4] and vegetation changes contribute to an elevated wildfire risk. Across the Arctic, wildfires are a growing threat.[5] A few years ago, Siberia was especially affected by wildfires,[6] but today this is a circumpolar challenge in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic.

Although the term wildfire might lead to the assumption that this is mainly a problem of rural and remote regions, fighting wildfires is also a particular concern for fire departments in urban areas such as Anchorage, Alaska,[7] or Yellowknife in Canada’s Northwest Territories (NWT), which had to be evacuated in August 2023.[8] Many urban areas in the boreal Arctic and sub-Arctic are like islands in an ocean of trees (similarly, other settlements often are experienced as islands in vast expanses of tundra, or, like at the coasts of Greenland, occupy small spaces between the sea and the ice). At the edges of these boreal Arctic cities, towns and settlements, urban, including residential, areas touch forest areas. Like low-lying islands are at risk of devastating flooding during storm surges, Arctic towns and neighbourhoods are at risk from wildfires. This requires urban firefighters to prepare for different kinds of disasters than the fires in built-up areas that they are usually trained to deal with.[9] Other challenges for fire departments in boreal Arctic cities include limited infrastructures, including limited road infrastructures in residential areas.[10] Transport infrastructure that is sufficient for everyday uses in thinly populated regions can quickly result in dangerous bottlenecks in case large-scale evacuations become necessary.[11] Such challenges can also be found elsewhere, and international cooperation between those tasked disaster response and prevention could use such practical commonalities as starting points.

In a single month, June 2019, Arctic wildfires caused the release of 50 megatons of carbon-dioxide into the atmosphere.[12] This is about the same amount that the entire country of Sweden emits of the course of a whole year.[13] In 2020, Russia’s Sakha Republic was the Arctic region that was most affected by wildfires, also other parts of Russia contributed significant greenhouse gas emissions from wildfires.[14] This problem is growing,[15] what was not long ago seen as “extreme fire seasons”[16] and has for all practical purposes become the new normal as “climate change and forest fires [form] a vicious circle”.[17] The 2023 wildfire season was particularly severe in the Arctic, especially in Canada,[18] which experienced “the worst wildfire season on record”.[19] In June 2023, smoke from wildfires in Canada caused dangerous levels of air pollution in major population centers along the East coast of North America, including in New York City.[20] Already by mid-October 2023, the NWT had suffered more than 180 wildfires.[21] In Quebec, the severity of wildfires in 2023 was “50% more intense, and seasons of this severity [are] at least seven times more likely to occur”[22] in the future. The 2023 wildfires in Canada raise serious issues in the context of the social and legal dimensions of disaster risk reduction as they “had disproportionate impacts on indigenous, fly-in, and other remote communities who were particularly vulnerable due to lack of services and barriers to response interventions”[23] These challenges can exist similarly in other parts of the Arctic that are also sparsely populated and lack infrastructure. But the effects of Arctic wildfires are not limited to the Arctic: “The consequences of the [2023 Canadian] wildfires reached far beyond the burned areas with displaced impacts due to air pollution threatening health, mobility and activities of people across North America.”[24]

In responding to the experiences of the dramatic 2023 wildfire season, the NWT’s Minister of Municipal and Community Affairs, Vince McKay, advised the residents to get insurance and emergency kits and to make sure that they are prepared for possible wildfires.[25] The NWT government stated that “climate change means the territory can expect more frequent and more severe wildfires and floods, and that while they can’t make exact predictions about wildfire and breakup seasons, they can take steps to prepare.”[26]

In the Arctic, due to limited human and material resources, preparing for such disaster risks requires international cooperation. Despite its shortcomings, the Arctic Council continues to be the most relevant international forum for international cooperation in the region. On paper, the Arctic Council remains the institution most prepared to facilitate cross-border cooperation between the Arctic states. Due to Russia’s departure from Arctic cooperation in 2022, in practice, cooperation is limited to the seven Western Arctic states, which are united in NATO. Today, Arctic cooperation is transatlantic cooperation. Based on its earlier work, the Arctic Council in 2023 accelerated its wildfire initiative[27] that aims at bringing different actors together and to facilitate disaster risk reduction and disaster response efforts in the Arctic.

There are clear human and social dimensions to Arctic wildfires. “Wildland fires are a critical environmental concern with far-reaching ecological, social, cultural and economic implications.”[28] Wildfires contribute to air pollution in the Arctic.[29] This, in turn, affects human health. Arctic wildfires are a global problem, too, because of the global health effects from wildfires: “Every year, there are an estimated 340,000 premature deaths from respiratory and cardiovascular issues attributed to wildfire smoke”.[30] Wildfires also lead to displacement and to the loss of homes.[31] Indigenous communities are particularly at risk from wildfires because of their particular dependence on an intact natural environment:[32] “Arctic wildfires can hit Indigenous Peoples’ lands particularly hard, destroying food and water sources and disrupting their livelihoods and culture practices”.[33] Indigenous communities might also be at a higher-than-average risk of adverse effects of wildfires because they might be overlooked by policies that focus on population-dense areas or that might be based on lack of information or even colonial stereotypes. This elevated risk for marginalized groups is a problem the Arctic shares with other parts of the world.[34] The same is true for the long-term effects as “[t]he effects of wildfires linger long after the flames die down, hitting public health and wellbeing far into the future”.[35]

In recent years, the fact that there is no longer a fire season but that wildfires are a permanent problem has gained mainstream attention.[36]

In the words of Canadian writer, explorer and environmental expert Ed Struzik, the Arctic is the “part of the world [which] is going to be hit hardest from an ecological point of view. Wildfire affects so many of the specialist species in the Arctic most notably caribou. The more the tundra burns, the more the lichen and the forest burn, the less likely caribou will make it over the hump [and it is thought that] there will be small, shadow herds in the future, but nothing like the great migrations that we’re seeing now. Once lichen burns, it takes 60, 70, 80 years before it comes back and it’s one of the primary components of [the] diet”[37] of rangifer tarandus. Already today, reindeer and caribou[38] are threatened by climate change. Wildfires will kill more iconic Arctic animals by starvation, thereby threatening not only polar biodiversity but also livelihoods and cultures of peoples across the Arctic region.

Indigenous peoples have long been seen as a concern for the Arctic Council.[39] Importantly, indigenous representative organizations are key actors within the Arctic Council system. The Arctic Council’s founding document, the 1996 Ottawa Declaration, and the subsequent practice of the Arctic Council give indigenous peoples an elevated (bis still relatively limited) role in the making of international law.[40] This makes the Arctic Council also particularly qualified to take into account indigenous rights in any attempt to reduce disaster risks. Given the rapid increase in wildfires in the Arctic, the perspectives of local communities in the region are particularly relevant.

But Arctic wildfires are not only a regional problem. Climate change increases the risks of wildfires:[41] “Climate change causes and accelerates Arctic wildfires in several ways as rising temperatures create drier conditions and increase the number of lightning strikes – leading to a future with more and larger fires that are both more intense and stretch over a prolonged fire season. In turn, this creates a dangerous feedback loop as black carbon and other emissions are released into the atmosphere. For people living in the Arctic, fires can quickly become a threat to life and property, alter available food sources and degrade the air quality with damaging effects on their health”.[42]

While in the northern hemisphere, many wildfires are the result of human action, including arson and negligence,[43] climate change is making wildfires more likely, Climate change means an increase in the likelihood of lightning,[44] it slows the jet stream,[45] causes longer heatwaves,[46] makes soil drier,[47] increases the risks of pests, such as bark beetles, and diseases that are harmful for trees.[48] As a consequence, trees are more likely to die due to these effects of climate change.[49] This leads to more dead wood, which in turn increases the risk of more wildfires.[50] There is a vicious circle connecting wildfires and climate change.[51] That the Arctic is particularly affected by climate change is well-documented – for example “the Canadian Arctic is about 10 degrees (Celsius) warmer than average”.[52] The increasing likelihood of wildfires are one effect of human-made climate change on the region.

“As the increasing effects of climate change and land-use change make wildfires more frequent and intense, it is estimated that we could witness a global increase in the occurrence of extreme fires of up to 14 per cent by 2030, 30 per cent by 2050 and 50 per cent by the end of this century.”[53] A significant part of this growth will hit the Arctic. According to the Director of the United Nations Forum on Forests Secretariat with the United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Juliette Biao Koudenoukpo, “Climate change, unsustainable land use and deforestation are among the key drivers of wildfires. Climate change exacerbates wildfire risk through increased drought, high air temperatures, low relative humidity, dry lightning and strong winds.”[54]

While climate change is not the only factor that drives wildfires, climate change in the Arctic means that the areas in the Arctic that is suitable for plant (e.g. shrub) growth is growing.[55] Shrubs have a local isolating effect, resulting in a warmer soil.[56] Similarly, climate change in the Sub-Arctic also means a change in vegetation which can have different effects on the likelihood and spread of wildfires.

Often, climate change means more wildfire. But wildfires can also mean more climate change: wildfires contribute to the expansion of shrubs in the Arctic.[57] Even on this simple level, even when not taking into account the dangers posed by the large amounts of methane that were trapped in the rapidly melting permafrost and other issues and that are released due to the warming, we can see a dangerous feedback loop. Climate change makes wildfires in the Arctic more likely. Wildfires accelerate the loss of permafrost in the Arctic,[58] and in this way contribute to the release of methane into the atmosphere, which further accelerates climate change. This is repeated all over the Arctic. Arctic wildfires are made more likely by climate change and Arctic wildfires contribute to climate change.[59]

Since the late 1970s, the Arctic has been heating up four times faster than the global average.[60] The effects of climate change on the Arctic and Sub-Arctic are manifold but one of the most dramatic ways in which climate change affects the people who live in the circumpolar north are wildfires. 2023 has been a particularly dramatic year in this regard. While the international community is taking note, it remains to be seen if future disasters can be prevented effectively. The Arctic Council’s efforts are notable, but they also need to translate into practical results that contribute to protecting local residents in the region, including marginalized groups and people living in rural areas.

Endnotes & references

[1] European Commission’s Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (2023). Arctic Region | Wildfires 2018-2023 – DG ECHO Daily Map | 14/11/2023, https://reliefweb.int/map/canada/arctic-region-wildfires-2018-2023-dg-echo-daily-map-1411202, last accessed 17 September 2024.

[2] J. E. Walsh, S. Bigalke, S. A. McAfee, R. Lader, M. C. Serreze & T. J. Ballinger (2023). “Precipitation”, Arctic Report Card 2023, DOI: 10.25923/hcm7-az41.

[3] Arctic Council (2023). Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires in the Arctic, 19 October 2023, https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[4] See Yang Chen, David M. Romps, Jacob T. Seeley, Sander Veraverbeke, William J. Riley, Zelalem A. Mekonnen & James T Randerson (2021). “Future increases in Arctic lightning and fire risk for permanent carbon”, in: 11 (5) Nature Climate Change, pp. 404-410, https://doi.org/10.1038/841558-021-01011-y, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[5] For an in-depth look at developments of Arctic wildfires in recent years see Jessica L. McCarty, Juha Aalto, Ville-Veikko Paunu, Steve R. Arnold, Sabine Eckhardt, Zbigniew Klimont, Justin J. Fain, Nikolaos Evangeliou, Ari Venäläinen, Nadezhda M. Tchebakova, Elena I. P arfenova, Kaarle Kupiainen, Amber J. Soja, Lin Huang & Simon Wilson (2021). “Arctic fire regimes and emissions in the 21st century”, 18 (1) Biogeosciences, pp. 5052-5083, https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-18-5053-2021, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[6] Davide Cotti & Zitta Sebesvari (no year). Arctic Heatwave, Technical Report, Interconnected Disaster Risks 2020/2021, https://s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/interconnectedrisks/reports/Research/Arctic_Heatwave_TR_210906.pdf, last accessed 11 March 2024, at p. 9; The Associated Press (2020). “New NOAA report finds vast Siberian wildfires linked to Arctic warming”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 9 December 2020, https://rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2020/12/09/new-noaa-report-finds-vast-siberian-wildfires-linked-to-Arctic-warming, last accessed 11 March 2024; see also I.V. Canosa, R. Biesbroek, J. Ford, J.L. McCarty, R.W. Orttung, J. Paavola, D. Burnasheva, “Wildfire adaptation in the Russian Arctic: A systematic policy review”, in: 39 Climate Risk Management, article number 100481, DOI: 10.1016/j.crm.2023.100481.

[7] The Associated Press (2023). “Wildfires in Anchorage? Climate change sparks disaster fears”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 2 May 2023, https://rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2023/05/02/wildfires-in-anchorage-climate-change-sparks-disaster-fears, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[8] See e.g. Dustin Jones (2023). “Out-of-control wildfires in Canada force all 20,000 residents of Yellowknife to flee”, in: NPR, 27 August 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/08/17/1194388692/wildfire-yellowknife-canada-evacuation, last accessed 28 September 2024; Ian Austen (2023). “After 3 Weeks of Wildfire Exile, a City of 20,000 Returns”, in: New York Times, 6 September 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/06/world/canada/wildfire-yellowknife-evacuation-return.html, last accessed 18 September 2024; Pat Kane (2024. “Yellowknife’s Wildfire Evacuation Was Tailored for the Privileged”, in: The Walrus, 16 August 2024, https://thewalrus.ca/yellowknifes-wildfire-evacuation-was-tailored-for-the-privileged/, last accessed 18 September 2024.

[9] The Associated Press (2023). “Wildfires in Anchorage? Climate change sparks disaster fears”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 2 May 2023, https://rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2023/05/02/wildfires-in-anchorage-climate-change-sparks-disaster-fears, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.; see also Mike Rudyk (2023). “Yukon government to review this summer’s wildfire evacuations in Mayo, Old Crow”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 23 November 2023, https://recinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2023/11/23/yukon-government-to-review-this-summers-wildfire-evacuations–in-mayo-old-crow/, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[12] Arctic Council (2023). Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires in the Arctic, 19 October 2023, https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative, last accessed 11 March 2024; see also Gloria Dickie (2022). “Insight: Why Arctic wildfires are releasing more carbon than ever”, Reuters, 8 September 2022, https://reuters.com/business/environment/why-arctic-wildfires-are-releasing-more-carbon-than-ever-2022-09-08, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[13] Arctic Council (2023). Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires in the Arctic, 19 October 2023, https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[14] No author named (2020). Summer Wildfires in the Arctic Circle Set New Emissions Record, 3 September 2020, WWF, https://wwf.mg/?749191/summer-wildfires-record, last accessed 5 March 2024.

[15] See Even Jeffries & Catherine Perry (2020). “Fires, Forests and the Future: A Crisis Raging out of Control?, Gland & Boston: WWF & BCG, https://wwwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_fires_forests_and_the_future_report.pdf, last accessed 5 March 2024.

[16] Ibid., p. 9.

[17] Ibid., p. 10.

[18] Clair Barnes, Yan Bonlanger, Theo Keeping, Philippe Gachon, Nathan Gillett, Jonathan Boucher, François Roberge, Sarah Kew, Olivia Haas, Dorothy Heinrich, Maja Vahlberg, Roop Singh, Manon Elbe, Sajanika Sivanu, Julie Arrighi, Maarten van Aalst, Fredi Otto (2023). Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada, 21 August 2023, http://doi.org/10.25561/105981, last accessed 4 March 2024, pp. 2-3; on the 2023 fires in Canada’s North West Territories see Barry Scott Zellen (2024. “The Arctic Aflame: Intensifying Arctic Wildfires Present a Sobering Reminder that Climate Change Remains a Grave and Gathering Threat to the Arctic”, The Arctic Institute, 20 February 2024, https://thearcticinstitute.org/arctic-aflame-intensifying-arctic-wildfires-present-sobering-reminder-climate-change-remains-grave-gathering-threat-arctic, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[19] Nicole Martillaro (2023). “This has been the worst wildfire season on record. What could 2024 have in store?”, in: CBC News, 27 September 2023, http://cbc.ca/news/science/2024-wildfire-season-el-nino-1.6978559, last accessed 4 March 2024.

[20] The Associated Press (2023). “Smoke from Canadian wildfires forecast to reach Norway”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 8 June 2023, https://rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2023/06/08/smoke-from-canadian-wildfires-forecast-to-reach-norway, last accessed 11 March 2023.

[21] Center for Disaster Philiantrophy, 2024 North American Wildfires, no date, http://disasterphilantrophy.org/disasters/2024-north-american-wildfires/, last accessed 4 March 2024.

[22] Clair Barnes, Yan Bonlanger, Theo Keeping, Philippe Gachon, Nathan Gillett, Jonathan Boucher, François Roberge, Sarah Kew, Olivia Haas, Dorothy Heinrich, Maja Vahlberg, Roop Singh, Manon Elbe, Sajanika Sivanu, Julie Arrighi, Maarten van Aalst, Fredi Otto (2023). Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada, 21 August 2023, http://doi.org/10.25561/105981, last accessed 4 March 2024, p. 2.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Vince McKay, cited by Natalie Pressman (2024. “N.W.T. minister urges emergency preparedness ahead of ‘high-risk’ wildfire season”, in: Eye on the Arctic, 9 February 2024, http://rcinet.ca/eye-on-the-arctic/2024/02/09/n-w-t-minister-urges-emergency-preparedness-ahead-of-high-risk-wildfire-season, last accessed 4 March 2024.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Arctic Council (2023). Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires in the Arctic, 19 October 2023, https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[28] Ibid.

[29] See in detail Steve R. Arnold, Heiko Bozem & Kathy S. Law (2023). “Arctic Air Pollution”, in: Hayime Akimoto & Hiroshi Tanimoto (eds.), Handbook of Air Quality and Climate Change, Singapore: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2527-8_19-2, last accessed 25 March 2024.

[30] Even Jeffries & Catherine Perry (2020). “Fires, Forests and the Future: A Crisis Raging out of Control?, Gland & Boston: WWF & BCG, https://wwwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_fires_forests_and_the_future_report.pdf, last accessed 5 March 2024, p. 12.

[31] Ibid., p. 11.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid., p. 12.

[36] See e.g. Susie Nelson (2020). “‘Zombie’ fires smoldered beneath Arctic ice all winter then reignited, causing one of the region’s worst fire seasons in history”, in: Business Insider, 9 September 2020, http://businessinsider.com/zombie-wildfires-in-siberia-smoldered-beneath-ice-reignited-2020-9, last accessed 7 March 2024; On the phenomenon of so-called zombie fires see Shelly Sommer (2020). “The Arctic is burning in a whole new way”, Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, 28 September 2020, https://colorado.edu/instaar/2020/09/28/arctic-burning-whole-new-way, last accessed 11 March 2024; Alejandra Borunda (2021). “‘Zombie fires’ in the Arctic are linked to climate change”, in: National Geographic, 19 May 2021, https://nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/zombie-fires-in-the-arctic-are-linked-to-climate-change, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[37] Gloria Dickie (2017). “Answering Some Burning Questions About Arctic Wildfire”, in: The New Humanitarian, 5 September 2017, https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/arctic/community/2017/09/05/answering-some-burning-questions-about-arctic-wildfire, last accessed 8 March 2024, quoting Ed Struzik.

[38] Disregarding small artificially introduced herds, rangifer tarandus are referred to as caribou in North America and as reindeer in Europe and North Asia. While forming several sub-species, the dietary needs of reindeer are similar across the circumpolar north.

[39] See Edward Alexander & Evan T. Bloom (2023). The Arctic Council and the Crucial Partnership Between Indigenous Peoples and States in the Arctic, Polar Points No. 21, 27 July 2023, http://wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/no-21-arctic-council-and-crucial-partnership-between-indigenous-peoples-and-states-arctic, last accessed 7 March 2024.

[40] Timo Koivurova & Leena Heinämäki (2006). “The participation of indigenous peoples in international norm-making in the Arctic”, in: 42 (2) Polar Record (2006), pp. 101-109, doi: 10.1017/S0032247406005080.

[41] Clair Barnes, Yan Bonlanger, Theo Keeping, Philippe Gachon, Nathan Gillett, Jonathan Boucher, François Roberge, Sarah Kew, Olivia Haas, Dorothy Heinrich, Maja Vahlberg, Roop Singh, Manon Elbe, Sajanika Sivanu, Julie Arrighi, Maarten van Aalst, Fredi Otto (2023). Climate change more than doubled the likelihood of extreme fire weather conditions in Eastern Canada, 21 August 2023, http://doi.org/10.25561/105981, last accessed 4 March 2024.

[42] Arctic Council (2023). Norwegian Chairship Launches Initiative to Address Wildland Fires in the Arctic, 19 October 2023, https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-arctic-wildland-fires-initiative, last accessed 11 March 2024.

[43] Even Jeffries & Catherine Perry (2020). “Fires, Forests and the Future: A Crisis Raging out of Control?, Gland & Boston: WWF & BCG, https://wwwfeu.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/wwf_fires_forests_and_the_future_report.pdf, last accessed 5 March 2024, p. 5.

[44] Ibid., p. 10.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Danielle Bochove (2023). “How Arctic ice melt raises the risk of far-away wildfires”, in: Phys.org, 13 Junue 2023, http://phys.org/news/2023-06-arctic-ice-far-away-wildfires.html, last accessed 7 March 2024; see also On the feedback loop between climate change and Arctic wildfires see Kat Kerlin (2022). “Unprecedented Arctic Wildfires Fuel Climate Warming Cycle”, UC Davis, 8 November 2022, https://ucdavis.edu/climate/news/unprecedented-arctic-wildfires-fuel-climate-warming-cycle, last accessed 11 March 2024; Eric Reston (2021). “Arctic Fires Are Melting Permafrost That Keeps Carbon Underground”, in: Bloomberg, Green-Energy & Science, 13 December 2021, http://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-13/arctic-fires-are-melting-permafrost-that-keeps-carbon-underground, last accessed 22 March 2024.

[52] Prof. Julienne Stroeve cited by Danielle Bochove (2023). “How Arctic ice melt raises the risk of far-away wildfires”, in: Phys.org, 13 Junue 2023, http://phys.org/news/2023-06-arctic-ice-far-away-wildfires.html, last accessed 7 March 2024.

[53] Juliette Biao Koudenoukpo (2023). “As Wildfires Increase, Integrated Strategies for Forests, Climate and Sustainability are Ever More Urgent”; in: UN Chronicle, 31 July 2023, https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/wildfires-increase-integrated-strategies-forests-climate-and-sustainability-are-ever-0, last accessed 22 March 2024.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Yanlan Liu, William J. Riley, Trevor F. Keenan, Zelalem A. Mekonnen, Jennifer A. Holm, Qing Zhu, Margaret S. Torn (2022). “Dispersal and fire limit Arctic shrub expansion”, in: Nature Communications 13:3843, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1048197/v1, last visited 25 March 2024, p. 2.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid., p. 4.

[58] See also Diana Yates (2021). “Study: Fire hastens permafrost collapse in Arctic Alaska”, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign News Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/852889507, last accessed 8 March 2024; Yaping Chen, Mark S. Lara, Benjamin M. Jones, Gerald V. Frost & Feng Sheng Hu (2021). “Thermokast acceleration in Arctic tundra driven by climate change and fire disturbance”, in: 4 (12) One Earth, pp. 1718-1729, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.11.011, last accessed 8 March 2024.

[59] No author named (2020). Summer Wildfires in the Arctic Circle Set New Emissions Record, 3 September 2020, WWF, https://wwf.mg/?749191/summer-wildfires-record, last accessed 5 March 2024. See maps on this correlation at Flavio Justino, David H. Bromwich, Vanucia Schumacher, Alex da Silva & Sheng-Hung Wang (2022). “Arctic Oscillation and Pacific-North American pattern dominated modulation of fire danger and wildfire occurrence”, in: 5 npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, Article number 52 (2022), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00274-2, last accessed 8 March 2024, p. 5.

[60] M. Rantanen; A. Y. Karpechko; A. Lipponen, A. et al. (2022). “The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979”, 3 Nature Communications Earth & Environment 168, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3, last accessed 18 September 2024.