Legal Guarantees for Freedom of Religion

The legal provisions in force in Poland set up standards for respecting freedom of and from religion. These provisions apply to all persons who find themselves within their territorial reach, regardless of whether they are citizens of Poland or other states or stateless persons residing in Poland. The standard of religious freedom is also not affected by the gender, ethnicity, race and age of a person. So it can be stated that the Polish national law and the international legal system serve as the basis for protecting the human right to freedom of religion and for exercising this freedom in educational settings.

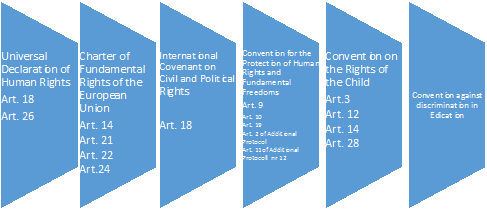

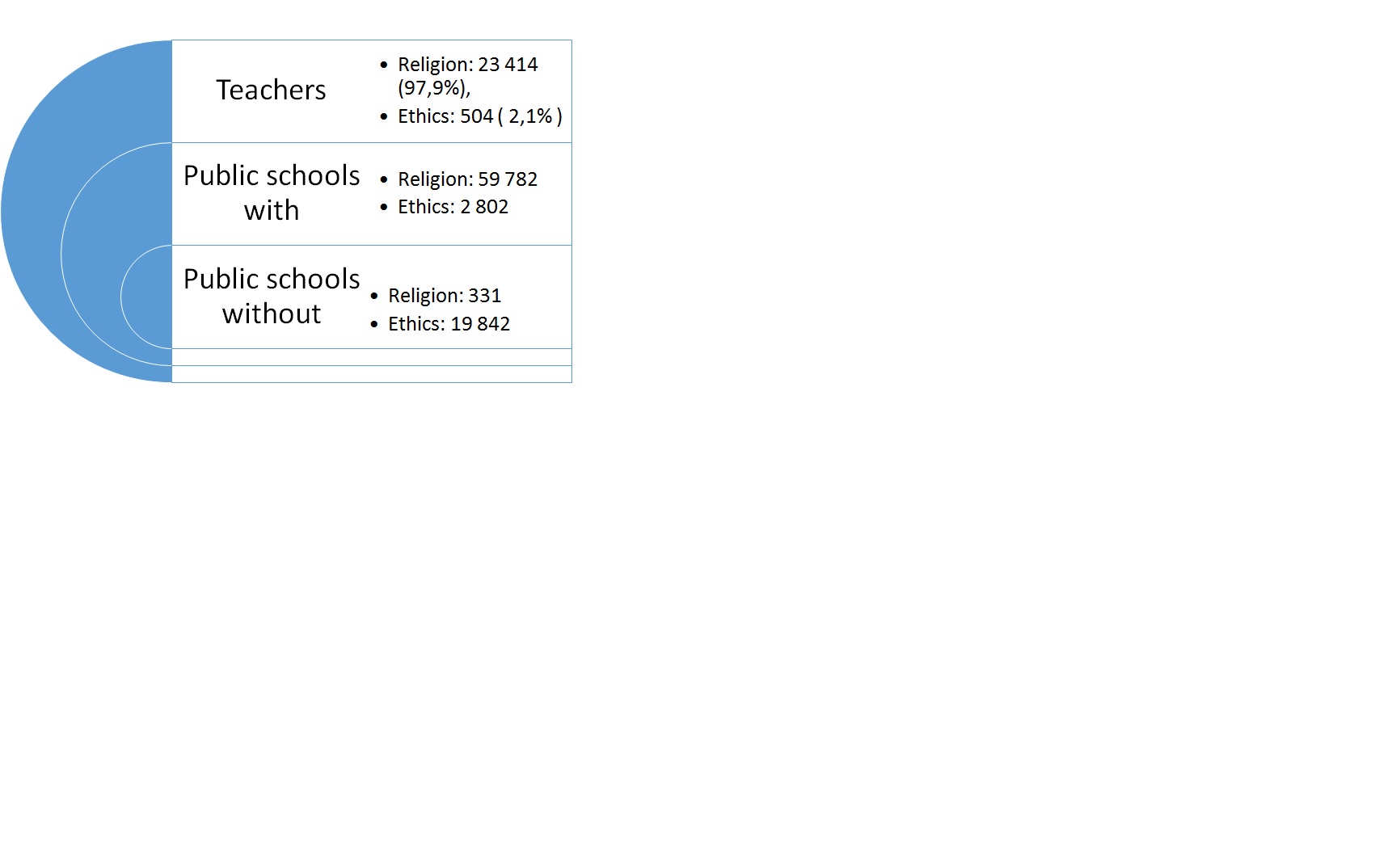

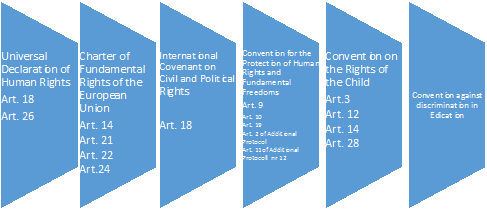

The provisions of international law, to which Poland is a party, establish legal guarantees as to religious freedom, especially the freedom of worship and religious practices. Regarding the relation between education and people’s opinions about religion or in particular the lack of such; quite apart from the provisions applicable to all people regardless of their age, the regulations of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and articles 14 and 24 of the European Charter of Fundamental Rights are of special importance.

Fig. 1 The international legal system safeguarding the freedom of religion and from religion in Poland

The system of national law in Poland guarantees the freedom of religion and the freedom from religion, yet the analysis of the legal system leads to the conclusion that Catholicism is the religion of the majority, which brings about particular consequences and risks for the human rights sphere.

The Polish Constitution fully respects the international standards of human rights protection as regards the freedom of belief and religion. This includes prohibiting the public authorities from commanding a person to disclose their philosophy of life, religious convictions or beliefs. The right to freedom of and from religion is guaranteed by Article 53, para. 1 of the Constitution, which states that “freedom of conscience and religion shall be ensured to everyone”. As stated in para. 2 of the same article, “freedom of religion shall include the freedom to profess or to accept a religion by personal choice as well as to manifest such religion, either individually or collectively, publicly or privately, by worshipping, praying, participating in ceremonies, performing of rites or teaching”. What is more, according to para. 6, “no one shall be compelled to participate or not participate in religious practices” and “no one may be compelled by organs of public authority to disclose his philosophy of life, religious convictions or belief” (para. 7).

Moreover, Article 25 of the Constitution places on the public authorities the obligation to remain impartial in matters of personal conviction, whether religious or philosophical, or in relation to outlooks on life.

Legal Regulation of Matters of Belief in the Spheres of Education and Upbringing

The Polish constitution guarantees the right of the parents to ensure their children a moral and religious upbringing and teaching in accordance with their convictions, while taking into account the freedom of conscience and belief of their children. As stated in art. 48, para. 1 of the Constitution,”Parents shall have the right to rear their children in accordance with their own convictions. Such upbringing shall respect the degree of maturity of the child as well as his freedom of conscience and belief and also his convictions”. In addition, according to Art. 53, para. 3, “Parents shall have the right to ensure their children a moral and religious upbringing and teaching in accordance with their convictions”. Parents thus have a subjective right towards the state with regard to their views on religious or lay upbringing of their children, although this right is limited and counterbalanced by the child’s right to have their religious convictions and beliefs respected.

There is, however, one provision in the Polish Constitution, which allows religion to be taught at school. According to Art. 53, para. 4, “the religion of a church or other legally recognized religious organization may be taught in schools, but other people’s freedom of religion and conscience shall not be infringed thereby”. The Catholic religion is not mentioned explicitly, but the Constitution states that the provision applies to a religion that is legally recognized. At present, there are 178 registered operational religious communities in Poland.

As follows from the case law of the courts, the right of the parents to raise children in the spirit of a particular worldview does not mean that the knowledge transmitted at school will be consistent with this worldview. Such an opinion was expressed by both the Polish Constitutional Court (Judgement of the Constitutional Court of 27 May 2003, on the provisions of section 97 paragraphs 3 and 4 of Act No. 127/2005Wyrok Trybunału Konstytucyjnego z dnia 27 maja 2003 r., ref. K 11/03, OTK-A 2003, No. 5, pos. 43) and the European Court of Human Rights (Judgement by the ECHR of 7 December 1976 in the case of Kjeldsen, Busk, Madsen and Pedersen v. Danemark application No. 5095/71, Judgement by the ECHR of 13 September 2011 in the case of Dojan and Others v. Germany, application No. 319/08). The case becomes more problematic; however, when children only learn about one religious worldview at school, something which comes close to indoctrination, or when it actually takes the form of intentional indoctrination where religious knowledge is passed on while participating in the religious practices of one particular tradition and faith.

The provisions that have significant bearing on the issue of human rights in education as regards the problem of religion at schools are mainly affected by the Concordat – an agreement signed in 1993 between the Republic of Poland and the Vatican. Poland has pledged that public schools and kindergartens will organize classes in Catholic religion and grant the Church the right to decide on its teaching programs, textbooks, and the persons teaching religion – including secular catechists, priests, monks and nuns, who have been granted permission to teach by the diocesan bishop.

The anti-discrimination provisions and the provisions securing the rights of the followers of other religions within the educational system and beyond are also in effect. Discrimination on religious grounds in Poland is forbidden according to the provisions of the Constitution and international law. However, victims of discrimination are not able to benefit from the legal measures provided by the Act implementing EU regulations, pertaining to equal treatment and the pursuit of compensation on its basis. This Act only prevents unequal treatment in education on account of race, ethnic origin or nationality (Art. 7).

It can be concluded that the Polish law introduces the standards of religious freedom, but it should be considered whether this standard is not a façade which hides the lack of equality. Because justice is not a dictate of the majority, the effectiveness of anti-discrimination instruments and the actual existence of response mechanisms for possible instances of minority discrimination need to be scrutinized and evaluated.

Dilemmas Pertaining to Teaching Religion in Public Educational Institutions

The main issue to consider when analysing the relation between education, religious matters and ethical principles is whether religion and ethics should be taught at schools and if so, how. Related questions are, first of all, whether teaching religion should also include participating in religious practices. The second question is whether the State should be neutral in terms of worldview and whether ethical issues should be taught through the lens of the legal protection of human rights. And the third question is whether religious matters should be discussed from the anthropological standpoint so that children could learn about the various belief systems that exist in the world.

It seems that these issues have long been resolved in the “old” European Union countries. Nevertheless, Poland is a peculiar state in which, after almost 30 years of teaching religion in public schools, we begin to ask these difficult questions anew. Poland is relatively uniform in terms of cultural and religious convictions and practices. There is a strong and increasingly stronger dominance of Catholic discourse in the Polish culture and public life. But the matter here is not so much about the numbers than it is about one of the most important issues in democracy. It is about honouring the rights of the minority to be respected in their beliefs and values and modes of social functioning. An analysis of the influence that religion and ethics have had on the society is difficult because everybody has a different value system. Values are part of human identity. The objective assessment of these problems is difficult in the actual circumstances. From the point of view of protecting human rights, it seems fit to evaluate the case of teaching religion in the context of law, which reflects certain universal values, developed and cultivated by the previous generations who had to find solutions to these problems before.

How Religion, Especially Catholic, entered into the Polish Education Institutions

The current regulations allow for teaching any religion that is registered in Poland, but originally the only religion taught in schools and later also in pre-schools was Catholicism, which found its way there due to pressure from the hierarchy of the Catholic Church. In order to fully understand the impact of the compulsory lessons in religion have had on the issue of human rights protection, the cultural and political circumstances behind the introduction of religion into the educational system need to be explained first.

Before religion became a school subject, children of the Roman Catholic faith could attend such classes at their parishes. These lessons were held in the so-called small classrooms, which looked like traditional classrooms, but were located either in the presbyteries or one of the parish buildings. Children from different religions either took non-institutional lessons or no lessons at all. Ethics was partially covered in the civic education course. But according to my experience, ethical dilemmas were discussed broadly in literature lessons while studying the Polish literary canon.

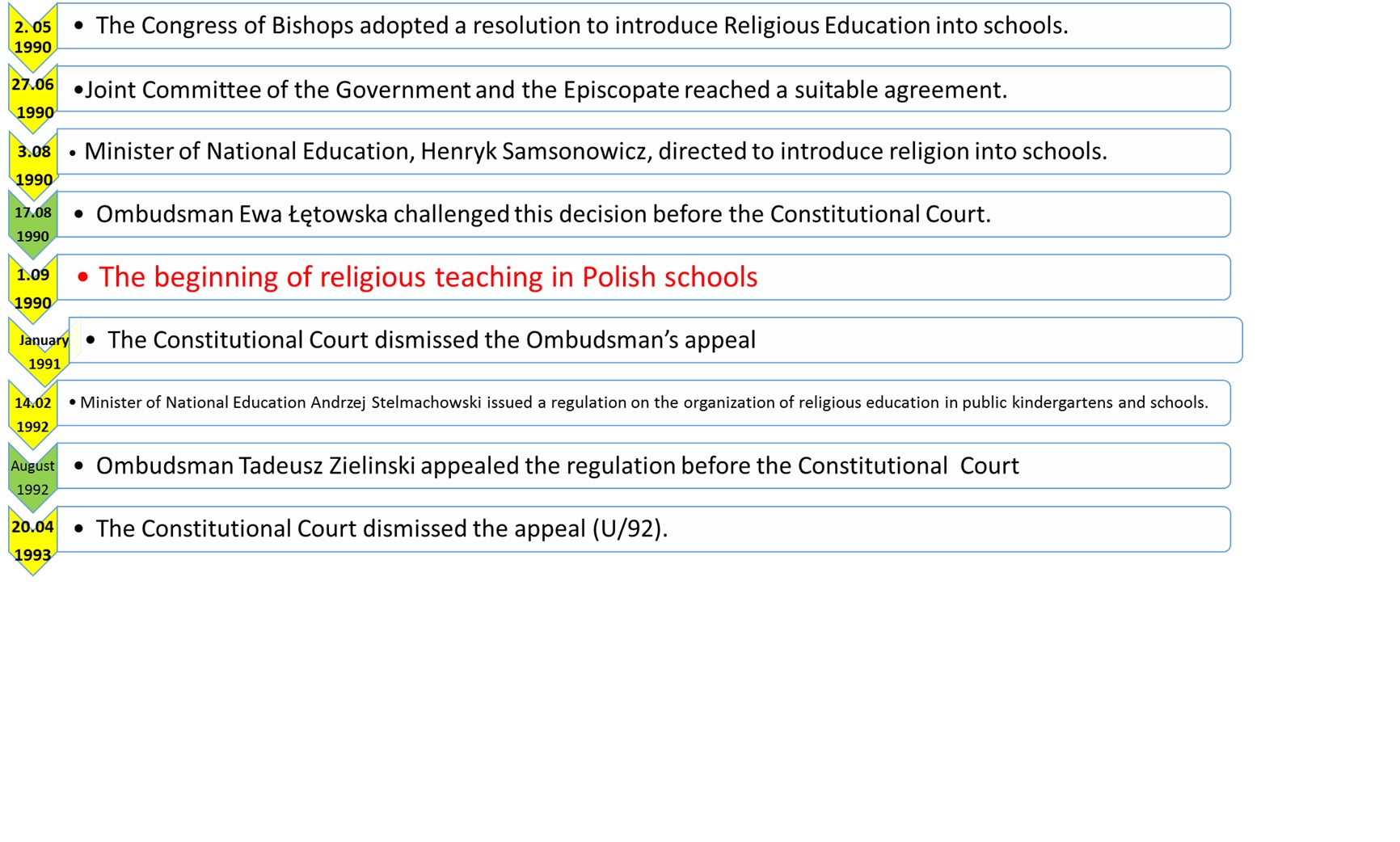

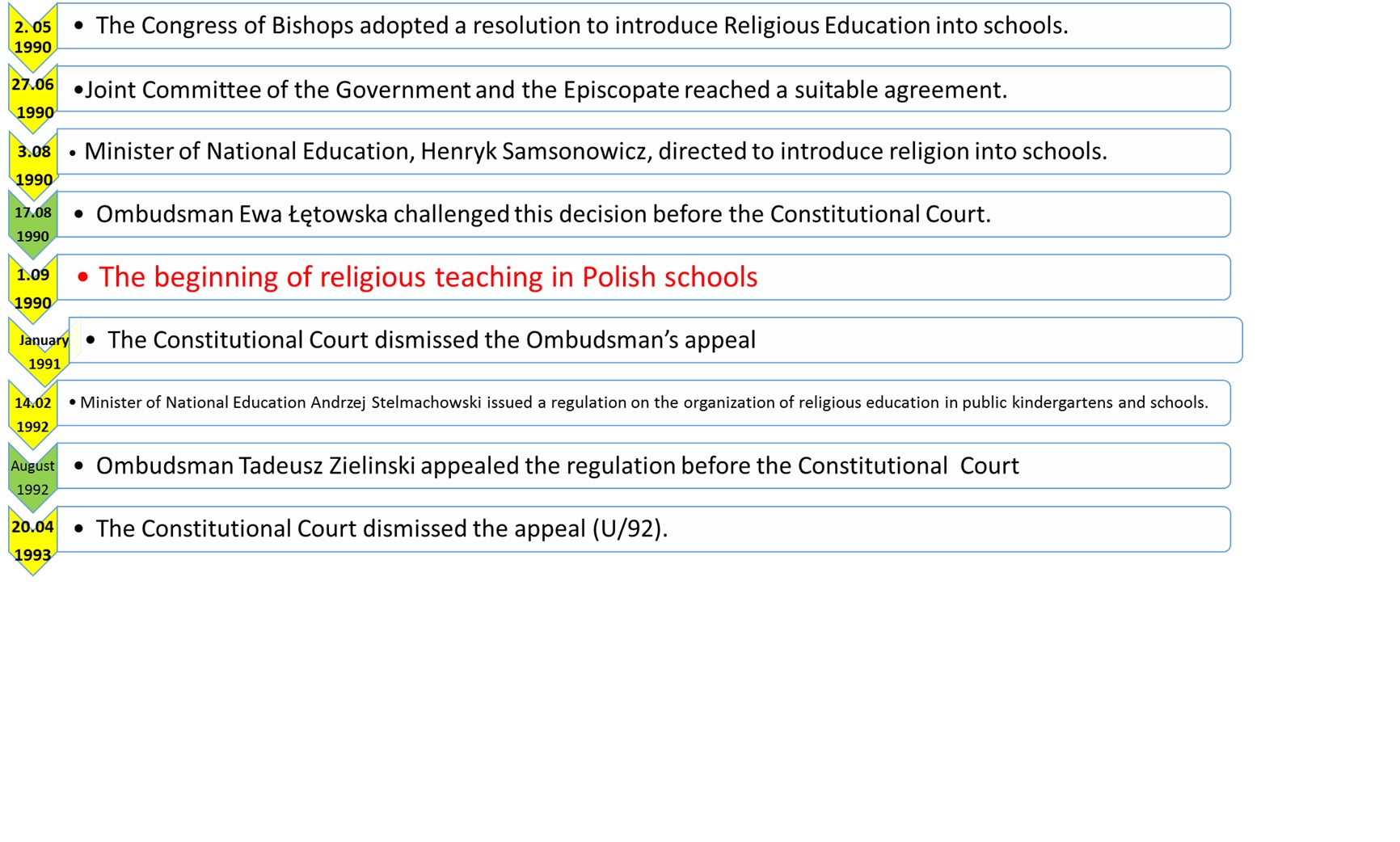

Religion was introduced into the Polish school system in September 1990, by virtue of a directive issued by the Minister of National Education on the 3rd of August 1990. At the time the act was illegal – as it would be illegal today. This was done at the express request of the bishops, who passed an official resolution regarding the matter at the Polish Bishops’ Conference and they threatened the Government to take legal action and organize social protests.

We should remember that Poland was in a very difficult situation at the time. The legislative power was held by a special constitution of the Sejm called the “contract Sejm”. It was made up in half from the Communists peacefully giving up power and in half of the Deputies chosen in a free election. The hyperinflation was raging. The Soviet Army was still stationed in Poland. The government wanted to defuse the social situation and was afraid of riots on religious grounds – even more so than in the Socialist period, the Church was heavily involved in the resistance against the Soviet Union and the Communist regime. It was at this moment the stereotype of the Polish-Catholic patriot was solidified. The Government took the opportunistic stand. They wanted to prevent further destabilization of the State and ensure a win in the upcoming parliamentary elections, so the blackmail happened to be effective.

One of the Government officials at the time, Jacek Kuroń, admitted: “I thought that we had avoided a religious war. But I was wrong. At once, critical voices were raised about trying to make Poland a religious state, which was all the more valid since we had broken the law – we, who talked so loudly about making the new Poland a state of the law!” (Kuroń and Żakowski 1997: p 182). It is often claimed that religion was sneaked into schools through the back door (e.g. Agnosiewicz 2002, Słowik and Beczek 2015). Introducing religious education classes were not approved by everybody and from the beginning it stirred many doubts related to civil liberties and human rights. This chart presents the formal stages of introducing religion into Polish schools (fig. 2 Chronology of educational curricula):

The decisions of the Government met with formal objections from the Ombudsman. Ewa Łętowska objected to the violation of the law, including the Constitution, provisions concerning the freedom of worship and laws regarding education. This was to little avail, as the Constitutional Court did not react accordingly. It stated, for example, that “the secular and neutral nature of the State” may not be a justification for teaching religion in public schools, but it also cannot be a justification for not allowing it to be taught. Legislative measures to introduce religion into schools were undertaken in 1992. Again, the Ombudsman raised an objection, which again was dismissed by the Court. In the end, grades for religious education began to appear on the school-leaving reports.

While the actions that led to the introduction of religion into schools in 1990 could be described as a blitzkrieg because they came as a sort of shock to the society, soon afterwards a heated debate began, which continues pretty much until today. Below are some exemplary quotes from the statements made by the Church officials and their supporters. These statements maintain the belief that religion is an expression of freedom from Communism and that Catholicism is linked to patriotism. As such, they stigmatize attitudes that do not adhere to the Catholic worldview. Jacek Kuroń cites the opinion of the bishops who commented on introducing religion into the Polish schools’ curricula. (Żakowski and Kuroń 1997: p.180 – 181.) In their opinion, ”Believers have the right to learn and develop their faith and since it is not possible to separate education from upbringing, schools are the right place for religious formation”. Moreover,”Return of religion to schools means the reparation of the harm the Polish society suffered under totalitarian rule that sought to banish God from people’s lives and to deprive Poles of their national identity”. The bishops also claimed that their fidelity to Christ’s teachings obliges them to preach and remind the entire world that schools are a natural place for evangelization. The matter was also commented upon by priests; the following is a representative example: “Freemasonry and other unbelievers, under the guise of freedom and neutrality, have suspended any relations with the living God” (Bartnik 1993, see: http://www.racjonalista.pl/kk.php/s,434).

Different argumentswere expressed by secular circles and those concerned about the “totalitarian” character of teaching just this one religion in schools. Some of these statements were made, for example, by the members of the Polish government at the time. They draw attention to the conflict-inducing nature of such actions and the threat that they pose to the freedom of persons who do not want to participate in religious education or who will only participate in them for fear of explicit or implicit discrimination and pressure.

Even then, technical problems as to the organization of these classes are signalled, which, as it turns out, has led to actual discrimination. Jacek Kuroń pointed to the negative implications of the fact that the state will teach religion under statutory coercion and he tried to salvage the situation of non-Catholics, stating that voluntary consent has to be a positive, not negative, decision for parents and pupils. He tried to substantiate his opinion with a claim that “introducing religion into schools threatens to create tensions and conflicts in many environments, not only between adults but also children”[1]. On the other hand, the then deputy minister, Anna Radziwiłł argued that universal Christian ethics should be part of education, but religion should not be taught as a school subject, because it is something greater. The representatives of the scientific and artistic circles and journalists then sent an open letter of protest to the Polish President, Prime Minister and The Minister of National Education, against the plans to introduce compulsory religious education in schools, in which they argued that “the initiative of the Ministry is aimed at turning state schools into denominational school which is the expression of undemocratic tendencies. They claimed, and rightly, as it turned out later, that ‘the choice: religion or ethics will be a false choice, given the Polish realities’.”[2]

Since 2007, grade in religion classes is placed on the school certificate and the Church has endeavoured to make religion one of the matura subjects(see: Wiśniewska 2016, see: http://wyborcza.pl/1,75398,20126283,religia-na-maturze-mozliwa-w-2021-r-kosciol-dogadal-sie-z.html?disableRedirects=true). Maturais a Polish state exam taken at the end of secondary school giving access to the University. Long-term observation of the political scene allows to conclude that the right-wing groups promised to acknowledge religion as one the matura subjects in exchange for the Church’s support for their candidates in the election.

The Importance of Catholic Religion in Poland

To understand the Polish case, one should be aware of how important the Catholic religion is in Poland as compared to other religions or atheism and what is the status of the ecclesiastical institutions in our country. Catholicism is very popular and, in a sense endemic here, as a worldview. Which is another reason why religious education (RE) has been taught at schools for about 30 years already.

The Catholic Church has an extremely well-developed and organized administrative structure, covering the entire Polish territory with a broad network of territorial units: parishes, dioceses, archdioceses and metropolies.

Fig. 3 The administrative structure of the Catholic Church in Poland and basic statistics. The Central Statistical Office of Poland Information note prepared in partnership with the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics SAC, Warsaw, 2017 (https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5500/7/1/1/struktura_administracyjna_kosciola_katolickiego_w_polsce.pdf)

Clearly, as far as human capital and organizational support are concerned, the organization of RE classes in public schools and kindergartens does not pose any problems to the Catholic Church, but given the situation, these classes could equally well be held at the parishes.

It is indeed difficult to assess how many Catholics there actually are in Poland, how many atheists and how many people of other beliefs. Official government statistics are based on data provided by religious associations, but other statistics are also considered. The authors of the report (cited below) observed a 3,2 million discrepancy in the number of Catholic Church followers, depending on the counting method. It should be noted that the Polish population is about 38 million.

According to the report, the statistics as of 2017 are as follows:

- 10 248 parishes,

- 30 925 priests.

- 33 214 800 believers – according to the Church.

- On average, there are 3241 followers in each parish and 1047 followers for one priest

The notion of a follower does not reflect fully the complex human relation to faith and religious duties. For this reason, the Church and public statistics do not indicate the actual number of practising followers, but rather the number of baptized persons. Thus, secular circles often allege that the official statistics, due to the opportunism of the Church officials, are highly inaccurate because they are based on the numbers provided by different religious denominations and their presentation is also not fully reliable.

In the general census, conducted in 2011,[3] 95% of respondents declared Catholic faith. As for other beliefs, 0,44 % of respondents declared the formal membership in the Russian Orthodox Church, 0,39% in the Jehovah’s Witness Association, 0,20% in the Evangelical-Augsburg Church, 0,9% in the Greek Catholic Church, 0,8% in the Pentecostal Church, 0,03% in the Mariavite Old Catholic Church, 0,02 in the Polish-Catholic Church and 0,2% in the Baptist Church. 0,12% respondents declared belonging to other religions and 2,41% declared themselves to be non-believers. These numbers have been obtained through a census that took into account only 20% of the households in Poland. What is more, 7% of the respondents refused to answer the question and for 1,6% it was impossible to obtain data. It is thus uncertain whether these statistics reflect actual social tendencies. What is also important here is that people who have been raised in some religion or just in certain social conditions, in which the existence of a higher power is implied, may not be able to declare atheism, even if they do not practice any religion at all. “They believe just in case, because you never know how it really is, and you wouldn’t want to mess with God.”

As a result, data showing that there is so great a domination of the Catholic worldview in Poland is not fully reliable. Still, the fact that it is presented in such a manner may lead to the occurrence of a phenomenon known as the Noelle-Neuman’s spiral of silence. According to this theory, people refrain from presenting their views when they believe that these views are not in agreement with the view of the majority (Noelle-Neuman 1974: p. 43-51).

Nevertheless, Catholic religion in Poland is dominant and this is visible in all spheres of social life. Many people go to church every Sunday. Baptisms, weddings, communions and funerals according to the Catholic rite are also common. This can be seen as an element of folklore, but also as the result of the strong, position of the church in Poland, which has been built over the last decades. Catholic priests are present during many state ceremonies and they bless newly constructed public buildings. Characteristic of the Polish landscape is spontaneously erected and maintained chapels. Not only in the villages, which were commonly conceived as the bastions of the traditional approach to life and religiousness, but also in the cities (cf. below: Pic.1 On the left is a rustic chapel in Bukowina, near Kudowa, on the right, a chapel in the Grochów District in Warsaw – the capital. Photo: M. Tabernacka).

It should also be noted that the Catholic Church receives considerable support from the public authorities. This support may be financial, organizational or institutional. An interesting example of this tendency is the Polish Post, the offices of which look like a combination of a devotional shop and a little rustic store that sells socks next to rosaries. Both pictures were taken in a Wrocław post office. Books that can be seen here are quite consistent in their subject matter. Some of them describe events from the history of Poland and the Polish people, but from a rather nationalist standpoint. There are also books written by priests and culinary books written by nuns and religious literature for children. Although “The Danish Way of Parenting” can also be spotted (cf. Pic.2. Photo: M. Tabernacka).

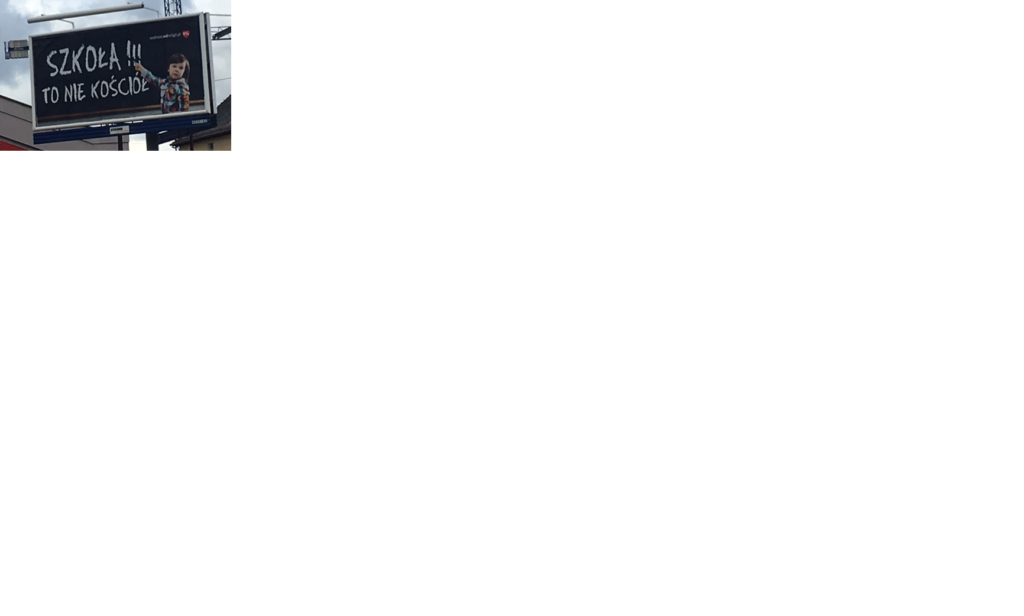

A certain counterbalance to these tendencies is provided by people with a secular outlook and non-Catholic religious beliefs and the actions they undertake in the public sphere. One example of such actions is the “School is not Church” social campaign run by the foundation called “Freedom from Religion”,[4] whose poster (with the same inscription) is shown on the photo below (Pic. 3. Photo: M. Tabernacka 2017).

The campaign’s authors insist on the secularization of the school and they are opposed to the domination of the Catholic religion, pointing out that the ever-presence of its symbols in schools is a symbolic violence that affects students from religious and non-believer minorities during the long years of education. The same foundation also promotes the freedom of worldview and the separation between the church and the state, which is guaranteed by the art. 25 of the Polish Constitution.

Both the Polish Constitution and a separate legislation ensure the separation of church and state. However, a number of legal regulations guarantees a privileged position to the Catholic Church and teaching religion in schools is just one of its consequences. About 30 years of publicly teaching RE in Poland may be one of the key factors determining the current escalation of xenophobic attitudes among young people who hide behind a specific perspective of patriotism that is closer to nationalism and religious ethnocentrism.

What Is the Teaching Practice of Religion in Polish Schools

According to Polish provisions, children can attend RE classes in all types of primary and secondary public schools. These can be in Catholic religion or any of the minority religion classes. Those who are not willing to be educated in religion can attend ethics classes if these are organized at their schools. If these are not organized, they can attend neither of the classes, at least according to the general principles derived from the law. But it is the practice of teaching religion in Polish schools that raises doubts about the preservation of human rights.

Legal regulations in Poland guarantee the freedom of religion and non-discrimination on the ground of religion. The problem lies, however, in the manner they are executed and in the specific social climate, which makes public authorities and certain individuals more inclined to opportunism towards the aspirations of the clergy and the Catholic community.

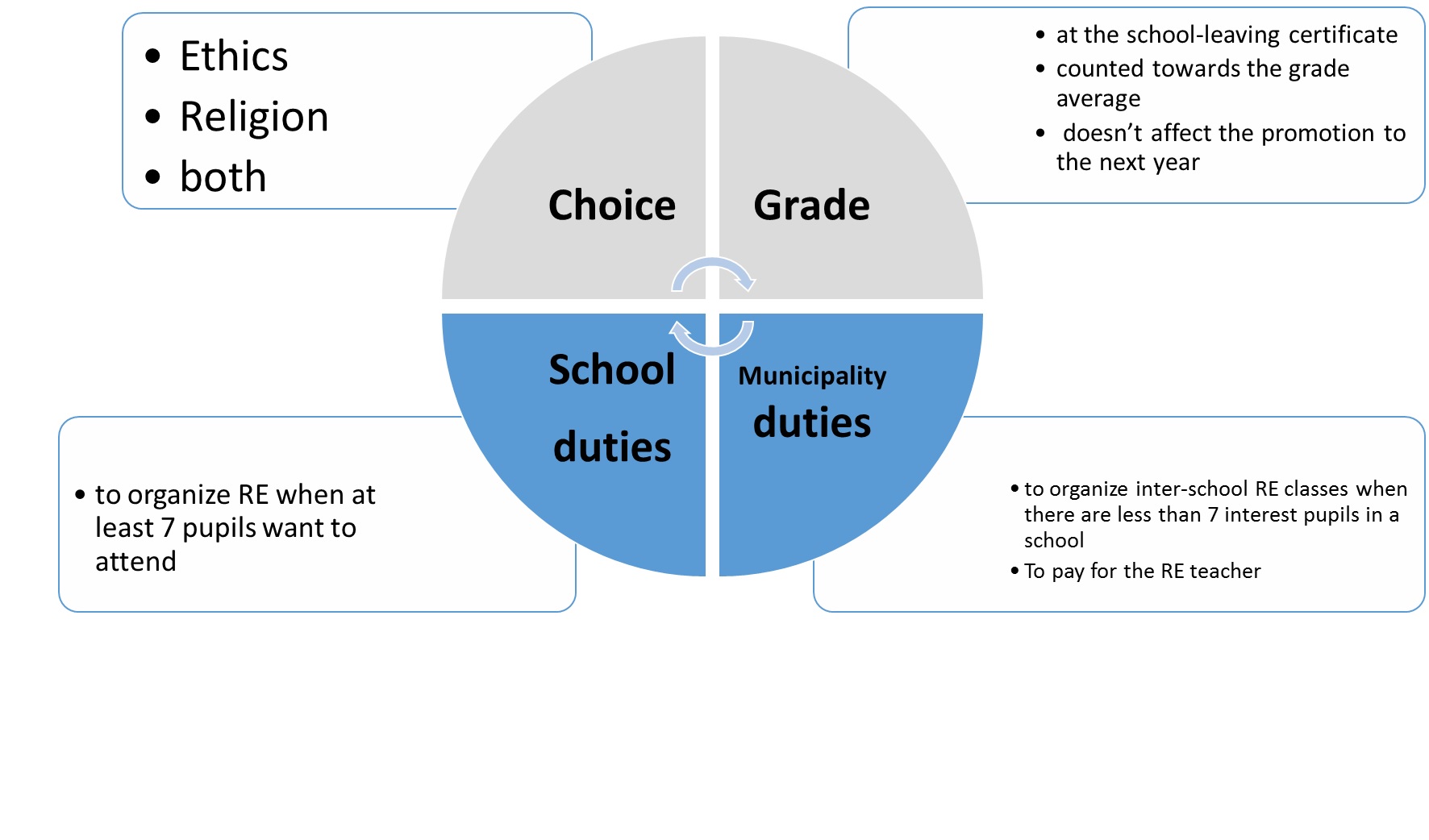

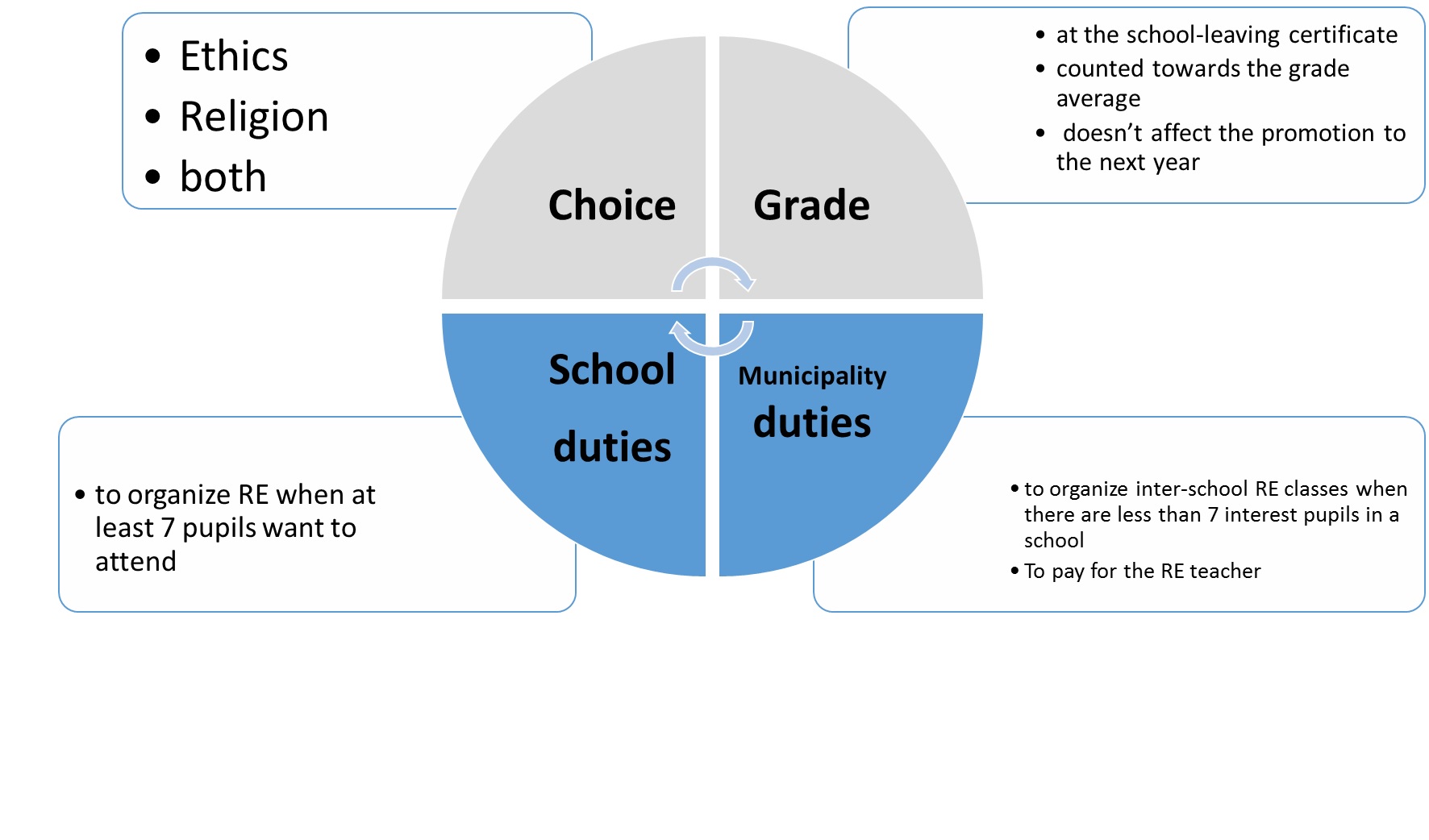

Attending or not attending RE has important implications for the Polish learners, because it affects the assessment of their overall school performance. The following diagram illustrates the specifics of organizing RE and / or Ethics in Polish schools in relation to the grades that learners can obtain (fig. 4 Organization of RE / Classes):

The organization of RE / ethics classes are regulated by the Regulation of the Minister of National Education of 14 April 1992 (Journal of Laws No. 36, item 155, as amended, the latest amendment of 1 December) regarding conditions and methods for teaching religion in public schools and kindergartens. According to this regulation, learners attending RE / ethics can get two grades, one grade or no grade at all. These grades count in the grade average, which makes them important for the assessment of the learners’ overall performance. If either ethics or religion are chosen, presence is mandatory just as for any other classes, so it may affect the grade for conduct.

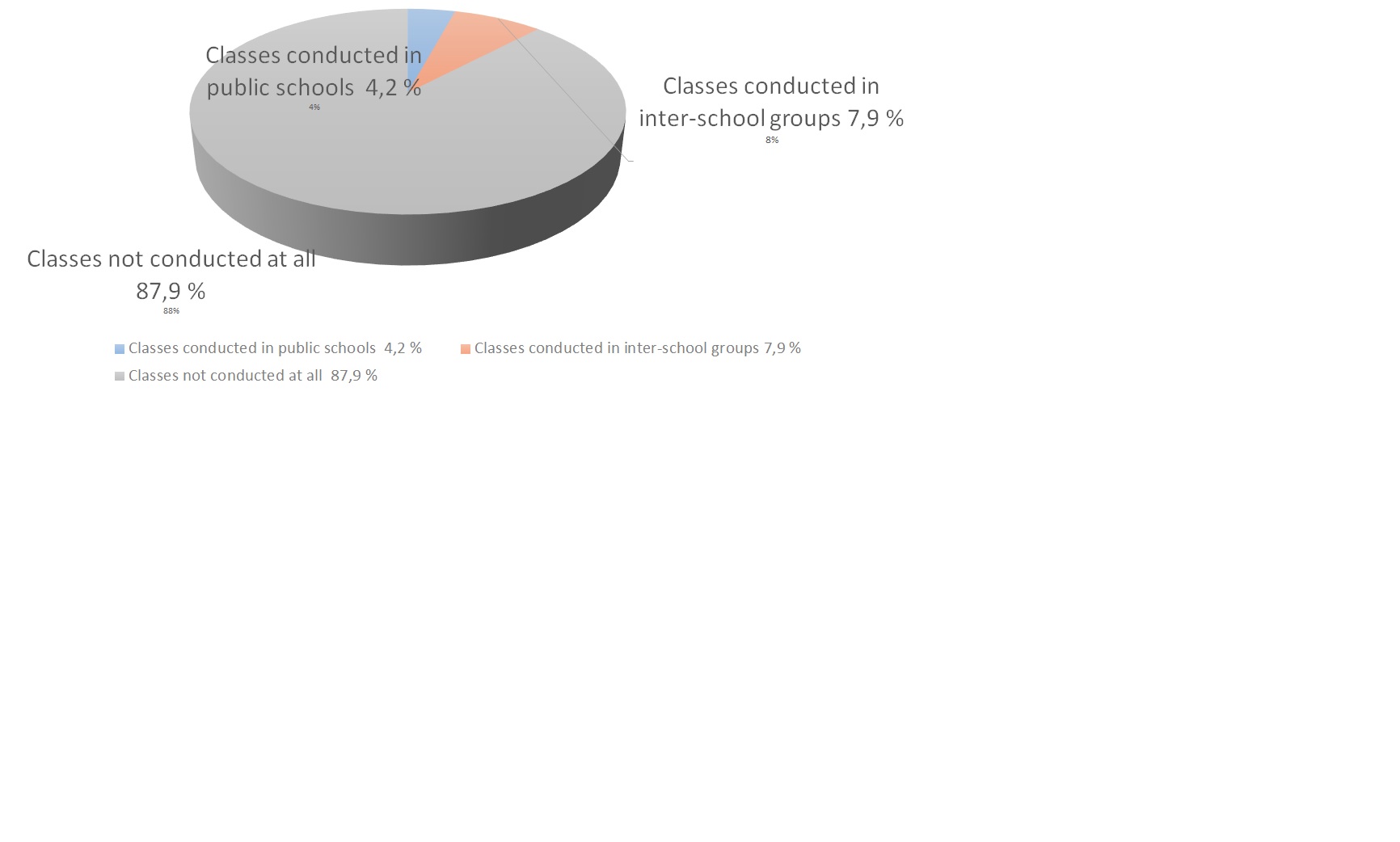

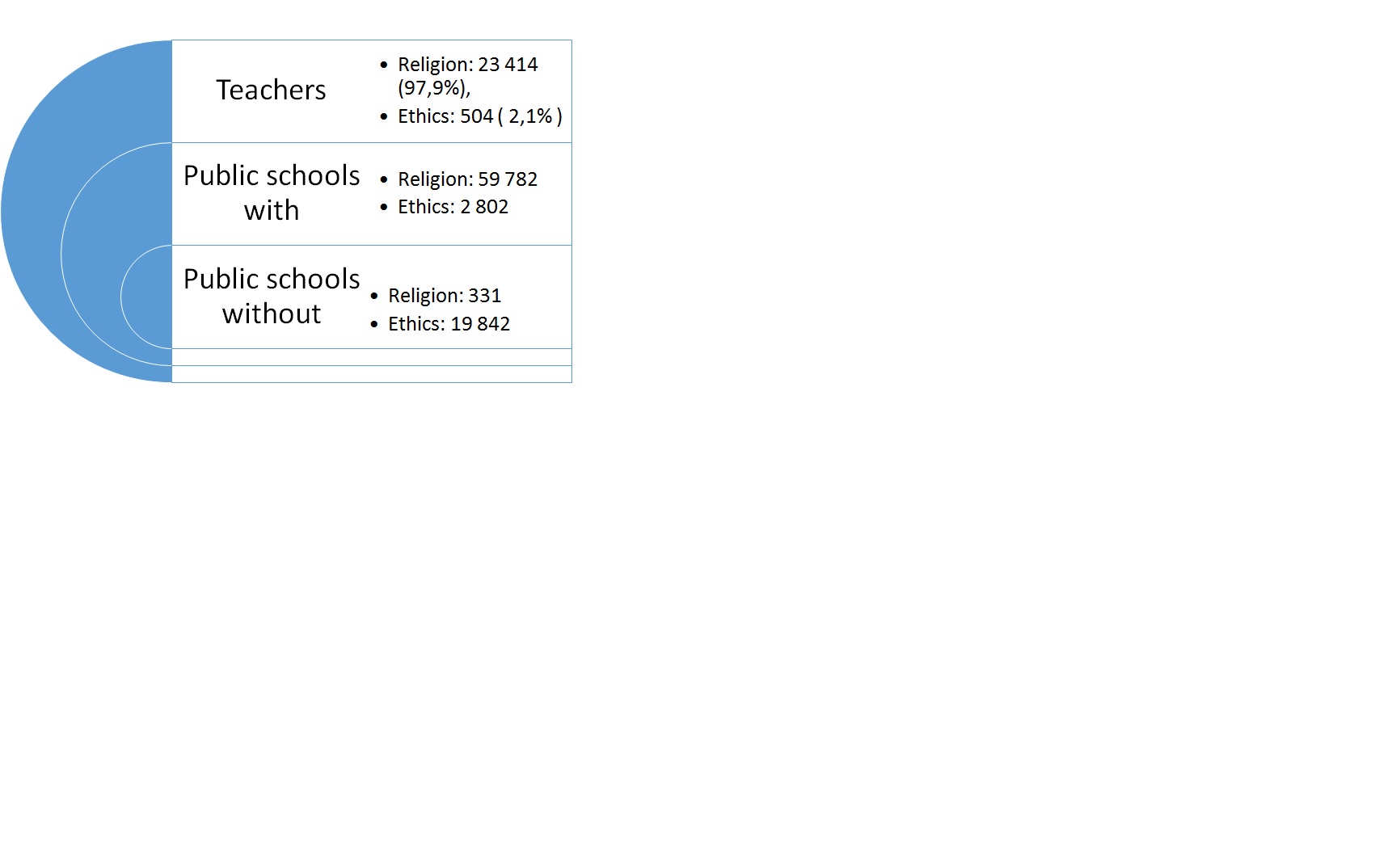

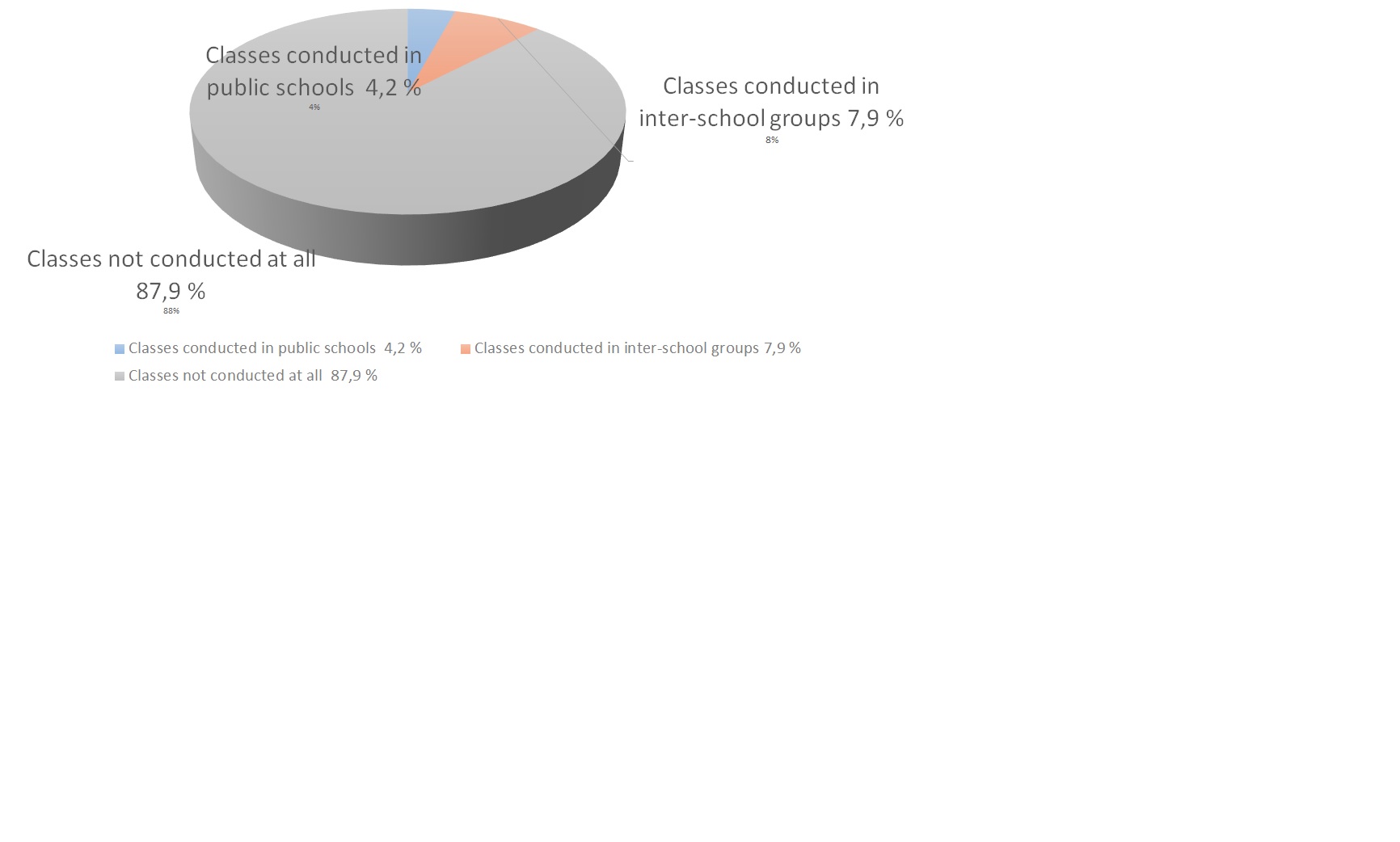

If there are 7 pupils in a school class or a kindergarten group who want to attend religion, the school or kindergarten is responsible for organizing such classes. If there are fewer than 7 pupils in a class or group, combined classes should be organized. If there are fewer than 7 pupils interested in attending RE classes in a school or kindergarten, the municipality is responsible for organizing classes for interschool or inter-kindergarten groups or at a religious education facility. The municipality is obliged to organize them even if there is just 1 such learner. The case is similar with ethics. In practice, the number of children attending ethics classes is small, even if it has increased in the last few years. The statistical data is presented below (fig. 5: Fig. 5, 2015 Annual Report of the Ombudsman. Source: M. Tabernacka):

Access to ethics classes in Poland was only taken seriously after the 2010 judgement of the European Court of Justice in Strasbourg in the case of Grzelak vs. Poland (Judgement of the ECHRights of 15 June 2010 in the case of Grzelak v. Poland, application No. 7710/02). The school authorities’ failure to organize ethics classes for a child who refused to attend RE classes was taken by the Court as an infringement of the articles 9 and 14 of the Convention. Nonetheless, even if ethics classes were formally guaranteed in schools, there were often doubtful cases from the standpoint of freedom of religion and conscience. There were some cases in Poland, where ethics classes were conducted by the same people who taught religion and on the basis of textbooks written by some Catholic priest or parents who opted for an ethics course were met with such proposals for these classes. Thus, when it comes to the actual safeguarding of human rights, the implementation of the provisions pertaining to teaching religion and ethics actually leads to the infringement of the standards for protecting human rights in Poland.

Teaching minority religions in Polish schools are, in fact, very rare. Under the current provisions in force public schools have the obligation to include the grade from any religion taught outside of the school system on the school-leaving certificate. The Ombudsman’s report showed that quite frequently the school authorities did not recognize such grades. The followers of minority religions who want to organize RE classes at schools often meet with a refusal by these authorities, their passivity or institutional obstacles, such as inconvenient hours (The 2015 RPO Report). The following chart illustrates the Polish educational practices for teaching minority religions (fig. 6):

The presence of the Catholic religion in schools goes far beyond the scope of an ordinary school subject in what regards the substance and organization.According to the law, two classes in Catholic religion should be held each week, or if it is only one, then the local bishop should give his permission. During the lessons, the pupils learn about the principles of the Catholic faith, but they also participate in religious practices, for example the classes tend to start with prayers. In fact, lessons are the combination of religious practices and theory from the textbook and workbook. This may pose a problem if schools cannot provide care or an alternative place to stay during the lessons to children who do not want to participate in RE and have to sit in class with other children. The organization of the Catholic holidays and retreats also calls for additional study breaks. The research conducted among children attending these lessons reveals that some of their contents verge on indoctrination. Children are shown propaganda videos (about miracles, conversions, etc.).

It is important to note that in Polish schools it is assumed that everyone will attend religion, but the regulations in force since 2014 (Journal of Laws of 1992 No. 36 item 155) explicitly state that religion is organized on the parents’ request or the learners’ themselves, after they have come of age, which stems from para. 1 of this regulation. The said request should be made in writing. The above chart presents the results of a study carried out by the Ombudsman in 2015.In many schools surveyed by the Ombudsman and schools which I researched, RE was simply a part of the agenda for all learners to attend by default. There was no practice of launching it on request and parents were not informed that such a request was a condition for the attendance of their children to such classes. Religion is simply placed on the class schedule, most often at a time convenient for the priest or catechist. The report that concluded the Ombudsman’s survey stated that in 70.4% of the schools surveyed, new students were automatically directed to take RE classes.If the learner didn’t want to participate, they could (or their parents could) report this orally (41.4%) or in writing (29%), 42% of principals explicitly stated that the schools they run do not inform learners and parents about the right to choose minority religion or ethics classes.

Both having a minority religion and ethics classes organized often require a great deal of determination from the learners and their parents, as these lessons often take place outside of school, in the so-called Inter-school classes and in inconvenient hours.

The law guarantees religious denominations and parents who adhere to specific beliefs the possibility to set up their own schools and such schools indeed exist. Parents representing these specific views can send their children to such schools without any obstacles, as it is also guaranteed by the law that a religious denomination can teach religion within their own structures.

The teaching of religion in Polish public schools points to numerous areas in which the right to non-discrimination and the freedom of worldview could be threatened. Economic determinants of state functioning considered in the light of the social justice principle, e.g. fair avocation of funds collected through taxes or total costs of the Polish education system are also relevant here. The law should not only safeguard certain rights but also provide mechanisms to counteract inequalities. Only such a legal standard can guarantee the protection of human rights in a given sphere. The Ombudsmanclaims that the current Polish regulations do not protect the various religious and social groups sufficiently. The persons belonging to the Roman Catholic Church have a privileged position: not so much due to legal regulations, but due to tradition, cultural practices and pragmatic considerations. The Ombudsman’s report points to the existence of hidden or passive denial of the rights of persons and groups representing religious or worldview minorities. The Ombudsman believes that legislative actions are less important than soft educational measures, appropriate mass media communication and a long-term policy for social education, which can bring about cultural changes (The 2015 RPO Report: p. 6-7).

The analysis of the legal provisions allowed me to distinguish a number of legal provisions pertaining to human rights in the field of education. They can be classified into three groups: first, freedom of religion, second, prohibition of discrimination affecting universal right to education and, third, provisions protecting the child’s mental and physical well-being. The rules in question will now be presented within the social context related to the presence of religion in the Polish public schools.

Freedom of Religion and Freedom of Thought

The principle of freedom of religion and belief is a fundamental human right, which obviously applies not only to adults, but also to children. It includes, among others, freedom to choose one’s religion, including the lack of it. One of the most important achievements of our civilization in the last 150 years has been the gradual refinement of the societies, which brought about the recognition of children’s subjectivity. As regards the guarantees for respecting human rights, another fundamental issue is the right of children to express and to demand respect for their views, including their religious views.

These standards are binding in secular countries with democratic systems. Any infringement of the principles regarding the freedom of worldviews and the freedom to choose one’s religion calls into question the actual secular and democratic nature of a state. Poland, according to the current Constitution, is both a secular state and a state following the model of democratic ruled by law.

It is extremely important to ensure that the prohibition against compelling anyone to participate in religious practices is complied with. This issue is related to whether RE will be taught as a school subject, whether it will aim to familiarize students with different religious systems and whether it will entail participation in religious practices. During the Religious Education lessons it may occur – and in Poland this is commonplace – that children say their prayers. Given the compulsory participation in such lessons this can be regarded as a violation of human rights.

Participation or non-participation in classes of religion in public school is an expression of a specific worldview or a particular religious or non-religious option. Even if a person who chooses one of these options does not intend to deliberately affirm anything, their choice can still become the subject of social evaluation. What is more, the consequences of making the choice and having it formally disclosed by placing the RE grade on the school certificate, are permanent, which further increases the risk of human rights infringement in the future and is already such an infringement itself. A related problem regards the assessment of the student’s participation or non-participation in RE within the context of the other classes that the school provides. According to the experts, placing a dash instead of a grade on a school certificate of a student who didn’t attend RE / ethics is regarded as illegal if ethics classes were not organized by the school. This violates the constitutional principle of not having one’s religious convictions disclosed and represents a breach of the right to privacy, guaranteed by Art. 18 of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (Olszewski 2010:p. 189-190).

One characteristic of teaching RE in Poland is that public education is subject to certain normative regulations that stem from a normative order that is not “public”. This also affects persons who are not willing to conform to this order. The public and legal relations of the state’s citizens should not be bound by regulations other than those provided by public law. This is one of the fundamental standards of democracy. The public law and its execution should thus not lead to the state of coercion, in which the process of performing public activities, the situation of individuals is affected by religious norms. Even if public law allows to be exempt from the operation of these norms, the actual social situation of an individual opposing the active, or even silent, will affect this individual’s right to religious freedom and freedom of convictions, which should be explored with regard to one more factor. As noted by J. S. Mill, “social intolerance, kills no one, roots out no opinions, but induces men to disguise them, or to abstain from any active effort for their diffusion”. According to the author, social stifling of “heretical” opinions allows to maintain the status quo of the intellectual climate, and to provide for comparative order, at least for some time. Yet, the price society has to pay for such an intellectual pacification is “the sacrifice of the entire moral courage of the human mind” (Mill 2012: p.128-129).

Freedom of religion and belief in the context of introducing religious education into schools should also be examined from the standpoint of the principle of proportionality operating in Poland by virtue of Art. 31 para. 3 of the Constitution. According to this regulation, any limitation upon the exercise of constitutional freedoms and rights may be imposed only by statute, and only when necessary in a democratic state for the protection of its security or public order, or to protect the natural environment, health or public morals, or the freedoms and rights of other persons. Such limitations shall not violate the essence of freedoms and rights. None of the conditions it outlines justifies restricting the scope of the principle of freedom of religion and belief, atheism included. Perceiving “minority” worldviews as immoral or “threatening” to the public order by the mere fact of their existence would be against the universal values expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including the right to freedom of thought and religion, guaranteed in Art. 18.

Even more so, that the preamble of this convention frames its underlying rationale as the following: “whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”. Big words from the preamble, stating that “disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people”, and that “it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law” should also apply to the legal obligation to ensure non-discrimination of religious minorities and persons professing no religion.

Ban on Discrimination

Discrimination related to teaching Catholic religion in Polish schools is thus a structural problem involving both specific organizational problems and organizational culture of the Polish educational establishments in general, derived from the broader social climate. This happens when the provisions create a condition in which, depending on the specifics of their implementation, discrimination will be either present or absent.

One example is the regulations of 1992 concerning the organization of RE which place the school principal in a very difficult predicament from the praxeological point of view. According to paragraph 1 of this article, lessons of religion in schools and pre-schools should be organized at the explicit request of parents or pupils, after they have reached the age of majority. But, as stated in para. 2, these lessons should be included into class schedules. Enrolment requests for school or kindergarten pupils should be made in writing. It is not technically feasible in multiple-class schools that RE will always be scheduled as the first or last lesson on a given day. These classes are often planned to take place in between other classes, which brings about serious logistical problems related to ensuring proper care to children who do not participate in them. This, in turn, causes schools to resort to measures resulting in discrimination of such children. It is also worth considering that statistical surveys conducted among both believers and non-believers conclude that the vast majority of the population (81%) thinks that RE classes should be scheduled either at the beginning or at the end of the school day so that persons who do not participate in them do not have to wait between lessons. Only one in eight persons surveyed (12%) does not endorse such a solution.[5]

An important question regarding the problem of discrimination is the question whether participation in RE is actually coerced. It emerges from my own research and the Ombudsman’s report (2015) that it is commonly “expected” in schools that all the school or kindergarten pupils will attend RE. Therefore, the catechists will commonly just enter the classroom and begin to conduct classes for all the children that are present. Also, contrary to the provisions of this Act, there are cases in which a written declaration of a child’s non-participation in RE classes is needed. At times, participation declarations ready to be signed were distributed among children at the beginning of a school year. Occasionally parents were required to hand in participation or nonparticipation declarations along with first-class admission forms. “Freedom from Religion,” foundation protested against such instances addressing the school management (e.g. the management board of the Integration Primary School No. 11 in Kielce), asking them to immediately change the first-class admission policy and remove any inquiries as to the candidates’ intention to attend or not attend RE. These inquiries were seen as having no legal footing and clearly violating Art. 53, para. 7 of the Polish Constitution as well as the provisions of educational law.[6].

The same tendency was pointed out in the RPO report (2015). On the other hand, as shown in the surveys conducted among the school principals, the practice of organizing RE classes for first graders is very routine. In 70.4% of the schools surveyed, new students were automatically directed to take Catholic religion classes. Only if the learner didn’t want to participate, could they (or their parents could) report this orally (41.4%) or in writing (29%). The active and prior, oral or written, declaration concerning the classes the student wishes to attend is taken by only one out of ten students (or their parents). Almost half (42%) of the principals surveyed explicitly stated that the schools they run do not inform learners and parents about the right to choose minority religion or ethics classes.

The Ombudsman’s report has also uncovered other actions that bear the distinguishing features of discrimination on the grounds of religion or worldview (The 2015 ROP Report):

- Not including the grade from minority religion classes on the school-leaving certificate. This grade is counted in the grade average, which results in unequal educational opportunities for these children.

- No remuneration for teachers of minority religions within the education system.

- Obstructing the organization of minority religion classes for children of the same age and insistence on creating combined groups for children. e.g. from the primary school’s year one up to six.

- Negative reaction to the parents’, adolescents’ and children’s willingness to participate in ethics classes, including dismissal of the request, apparent acceptance, but lack of further action; making children participate in RE, e.g. by informing that participation is compulsory, when it is voluntary according to the law.

Yet the data disclosed by the foundation “Freedom from religion” suggests that religious discrimination in Polish schools takes on other forms as well. These include school employees pressuring students to take part in religious ceremonies; what is more, school celebrations contain elements of Catholic religion. Discrimination and indoctrination are also present in many educational and upbringing activities, including school decorations (e.g. the domination of religious symbols in the classrooms and corridors, a plaque in the cafeteria which equates the students’ high personal culture with praying before meals, etc.).[7]

Any discrimination of social groups or individuals is detrimental to the society’s potential as is social pressure to ensure a complete worldview uniformity. J.S. Mill draws attention to the need to ensure liberty of thought and pointed at the socially negative consequences of the “tacit convention that principles are not to be disputed”. According to the author, no nation has developed or will develop in “an atmosphere of mental slavery” (Mill 2012: p.131). The observations of R. Wilkinson and K. Picket concerning equal opportunities in society (Wilkinson and Pickett 2011: 191-211) are consistent with this line of thought and can also be linked to the social effects of discrimination arising in schools out of teaching just one (Catholic) religion there. The lack of equality brought about by favouring just one religion creates divisions and undermines trust, leading to a dysfunctional society.

The ban on discrimination on religious grounds is also related to fair participation in public finances. In the case of teaching religion in Polish schools this is also closely linked to the principle of separation of church and state expressed in Art. 25 of the Polish Constitution. Public schools are financed from public funds and run by municipalities. The salaries of the priests and catechists teaching RE are drawn from public funds, but these teachers are appointed by the church authorities. Public supervision of their teaching is limited, which will be analysed in more detail below. The catechists have a formal status equal to teachers of other subjects – in terms of wages, working conditions and pension rights.

The unequal professional standing of catechists and teachers of secular subjects is pointed out by B. Olszewski (2010: p. 186 and 193-194) as one element in the structural conflict related to teaching RE in Polish schools. The author mentions that the catechists are employed in accordance with the Teacher’s Charter – a legal regulation concerning all Polish teachers – but their legal status is also influenced by the Church regulations and the decisions made by its representatives. One example is the manner of assessing their competences to teach, e.g. the bishops deciding who can teach religion in a given school. The catechists can also become members of the Teachers’ Board and acquire early retirement rights like other teachers, but they are not fully subject to normal supervision within the general education system.

The cost of organizing the Catholic religion classes is therefore borne by all taxpayers, regardless of their beliefs. The problem of financing RE lessons in public schools has been debated since 1990s. One of the main arguments brought forward by the opponents of financing RE from public funds has been that teaching just one single worldview is financed through taxes also paid by those who do not subscribe to this worldview. The creators of the civic project under a statutory initiative “Secular school”, started in 2015, put forward the following postulates: “Religion in schools – yes, but not paid for through our taxes – let it be financed through Church funds and disappear from the class schedule. They maintain that their initiative is not anti-Catholic nor anti-religious. On the contrary, “[they] are absolutely for religion being taught in schools but after the regular classes have ended, not alongside them”.[8] Opponents of public funding often refer to the opinion expressed by T. Jefferson: that it is unacceptable “to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves”. He considers this “sinful and tyrannical, and any attempt to do so threatens the religious neutrality of the state” (Agnosiewicz 2002: op.cit).

The prohibition to compel a person to disclose their convictions or belief is essential for the elimination of discrimination. However, when a particular religion is commonly taught at schools, this prohibition is actually violated, because the very fact of participating or not participating in RE classes is indicative of a certain worldview. If schools are to be neutral in terms of worldview, then religious matters could be taught in classes objectively presenting different religious and philosophical systems. What is specific about learning environments in general is that they foster frequent interactions between children who know relatively much about one another. Actively creating situations in which some of the children may feel inferior because they differ from the majority is a real discriminatory mechanism. Adolescence is a period fraught with conflicts and those who differ from others are subject to rejection and discrimination. In Poland, unfortunately, little attention has been paid to the shaping of egalitarian social attitudes, especially lately.

Any form of discrimination against learners who are the followers of minority religions or followers of no religion at all may prevent these learners from fully benefiting from their right to education. Vital aspects of this problem will be presented below, but it should be noticed that in the General Commentary to Art. 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Human Rights Committee has pointed out that public education which allows for teaching of a particular religion is not compatible with this Covenant. Unless it is possible to obtain an exemption from these classes without any discrimination or alternative classes are offered, taking into account the wishes of the parents and caretakers.

Universal Right to Education and the Prior Right of Parents to Decide on their Children’s Upbringing

To pass on certain religious views to children at school could impact the right to education. This right should be implemented on an equal footing for all entitled persons. Where there is an actual breach of the principle of equality by discriminatory practices in both peer groups and in the school-pupil relations, that right is infringed. There are some important problems here.

One problem is the right of children to care and that their well-being is taken into consideration. This includes the physical security such that a child will not be left unattended as well as the psychological comfort that a child will not feel excluded and, furthermore, that it will not be affected by the negative consequences of the fact that they do not attend certain classes due to a different worldview. Another issue is related to ensuring the safety of children in educational institutions. Yet another concerns the parents’ right to raise their children in accordance to their convictions. It is also important to ensure a sufficiently high level of schooling that is uniform across the entire state.

The parents’ attitude to the declaration of their children’s participation in RE classes would be influenced by a possible threat against their children’s physical security and psychological comfort. According to one such views, the pressure from the “worldview majority” is so strong that non-believers, as they themselves declare, choose to declare their children’s participation in catechesis and other religious practices for “social reasons”. Non-believers are often worried about their children’s well-being in the face of more and more frequently reported cases of social ostracism and violence[9].

This tendency already manifested itself in the early stages where RE was introduced in the Polish public schools, that is, in the 1990s. Studies reveal (NEUTRUM 1996) that parents and students preferred to avoid open and long-term conflicts with the school. In practice, such conflicts were resolved by the child’s departure from school or muffling the conflict for the sake of peace. The conflicts were thus resolved “quietly”, as the parents were afraid that the situation might affect their child. In order to avoid repercussions or out of a sense of duty to remain loyal to the representatives of the religion that they professed, they rarely resorted to institutional settlement of conflictual situations.

The fear of being subject to aggression in a situation where the education system does not guarantee the de facto equality of different belief systems is not unfounded. As noted by Wilkinson and Pickett (2011: p. 151-152 and 161), increased inequality raises the stakes in the fight for status and is responsible for the increase in aggressive behaviours. The authors draw attention to the fact that violence is a frequent reaction to being insulted or losing one’s face. In a situation where children being educated get a hint that another person is “different”, because he or she does not attend RE and does not belong to the majority that would give them a sense belonging to the “right” people, this may lead, especially if there’s no standard of respecting differences, to treatment that is humiliating to the affronted person and may cause them to retaliate.

In the words of R. Tyrała (2014: p. 320), non-belief is a discreditable stigma. According to the author, dealing with this stigma by hiding one’s non-belief may result from the balancing of profit and loss. His research shows that non-believing parents often submit to the pressure of their family environment and send their children to RE classes, even though a relatively higher percentage of non-believers decides against such a step. Yet, due to the lack of institutional mechanisms, the pressure from peers and teachers is still present in the lives of the children whose parents are non-believers (Ibidem: p.334-335).

According to Art. 3, para. 3 of the regulations on the conditions and method of teaching religion in public schools, schools are legally obliged to “guarantee care or general educational classes during the period of religion or ethics classes for students who do not attend religious classes”.It emerges from my research that the implementation of this obligation in practice may at times be improper, resulting in both uncomfortable and dangerous situations for children as well as stigmatization and discrimination.

I have documented instances in which a child was to be chaperoned into another class for the duration of these lessons, but often he just had to wait in the school corridors. He was not taken care of properly, so he had to be moved to a different school. In another instance a child whose parents declared that he will not participate in RE classes was given a choice to either wait in a school corridor or stay in the class for the duration of RE, during which, in order not to “stand out”, he stands up for the prayer like other pupils. He does not participate in the activities but should not disturb the others.This is a stigmatizing situation, affecting the individual’s universal right to education. A study conducted in Poland soon after RE classes were first introduced[10] revealed that the opinion of the students themselves is no different. According to the respondents, when all the students finished their classes and went either home or to the parish to attend RE, their school situation was more or less equal. Upon introducing RE, the “otherness” of the children who did not attend the classes had become a problem. They have been stigmatized by being labelled with epithets that equalled not attending RE with being a member of certain religious or social groups that are perceived negatively in the society[11].

The proper standard of schooling should also be ensured by appropriate control measures. Public authorities financing a given initiative should have a degree of influence or at least supervision over its most important aspects. When teaching a subject in school, religion included, these aspects include, above all, appropriate pedagogical preparation for teaching different age groups in a manner that is adequate for their physical and mental development as well as providing an appropriate content. According to para. 4 of the regulations regarding the conditions and method of teaching religion in Poland, the RE curricula and textbooks are developed and approved by the Church authorities and only forwarded to the Minister of Education. There are no constitutional or supervisory mechanisms to oversee the content of these textbooks and curricula. The obligation to employ a catechist is not equated with influence over who will actually be employed. As stated in para. 5 of the aforementioned regulations, a catechist is employed solely on the basis of a registered referral issued by the church authority – in Catholic Church this is diocesan bishops. Similarly, professional qualifications of catechists are assessed by the Church hierarchs – the Polish Bishops Conference, specifically, but here the provisions entail acting in agreement with the Minister of National Education. Taking everything into consideration, it cannot be stated that the Polish provisions introduce a universal standard of equality in religious instruction in public schools. What is most lacking are the instruments of control and supervision over the socially important aspects of such an instruction, including curricula and staff responsible for conducting the classes.

Conclusions

The case regarding the introduction of RE into the Polish public education system allows the observation of certain important tendencies and evaluate them from a relatively long-time perspective of 30 years of religious education. Common religious education in public schools can highly affect the functioning of a given society. Some consequences are also visible in the manner of functioning of certain religious communities, such as the Roman-Catholic parishes in Poland.

Paprzycki (2015: p. 10) notes, while analysing the problem regarding religious markets as they are related to the competitiveness of churches, that the Catholic Church in Poland after 1989, that is, after the fall of socialism, was faced with the challenges related to its former position of a monopolist that did not have to, as the beacon of patriotism and freedom, compete with other religious orders. For these reasons, Catholic Church in Poland has difficulties in communicating with the state and the society, including its followers. The author suggests that the Church officials often depend on the state’s help, especially legislation that is favourable to them and takes the burden of convincing people about their rights and values off their shoulders. It seems that this strategy, despite its “totalitarian” character or perhaps because of it, has been quite effective, which is reflected in increasing social support for religion in schools, as confirmed by statistics below.

The data shows an upward trend in the social acceptance of teaching RE in schools as well as a decrease in the number of its opponents, which is illustrated by the chart:

| Should religion be taught in public schools? |

Respondents’ answers by date |

|

|

| IX ‘91 |

IV ‘93 |

VII ‘93 |

I ‘94 |

VII ‘94 |

VII ‘07 |

| Definitely yes |

23% |

21% |

22% |

20% |

24% |

36% |

| Rather yes |

34% |

34% |

31% |

37% |

31% |

36% |

| Rather not |

23% |

19% |

18% |

19% |

19% |

12% |

| Definitely not |

19% |

22% |

25% |

19% |

22% |

12% |

| Hard to say |

1% |

4% |

4% |

5% |

5% |

4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Based on: Opinions about teaching religion. Research summary. Polish Public Opinion Centre (CBOS) BS/119/2007, Warszawa, Lipiec 2007 http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2007/K_119_07.PDF

When it comes to teaching kindergarten students, the same study reveals that public opinions are rather divided. A bit more than a half of respondents (53%) believes that religion should be taught in public kindergartens, while two fifths of them (41%) takes the opposite view.This does not change the fact that religious minorities and non-believers still need to have their rights protected.Their situation, taking into account the increasingly widespread acceptance of religion in public schools, is becoming more and more difficult.

The study also paints a picture of the content which, according to the Poles, should be taught in RE classes. More than a half of the people surveyed (57%) believes that these lessons should present knowledge about various beliefs and religions, while a bit more than one third of them (36%) thinks that the curriculum should concentrate mostly on the rules of the Catholic faith.The practitioners – teachers and scientists – are of similar opinion (Olszewski 2010: p. 194). This is also a proof for the existence of a certain cultural climate allowing for religious tolerance, which, in turn, should be used for promoting anti-xenophobic attitudes. This, however, does not translate into the respondents’ empathy regarding potential threats to the rights of those not professing the Catholic faith. The question: Can the hanging of a cross in public places, such as classrooms, be considered a violation of the freedom of non-believers? Was responded in the negative by 60% of the respondents and by only 33% in the affirmative. 7% did not give their opinion (CBOS, BS/170/2013).

Both in the 1990s, when introducing RE in schools (Kuroń and Żakowski 1997: p.182), and at present (Paprzycki 2015: p.61), attention has been called to the fact that turning religious education into a school subject that is not respected by the youth, strips it of its sacrum. Paprzycki notes that introducing RE in schools could be perceived as a kind of coercion and the result of an agreement between the church and the world of politics, which might cause teenagers to rebel. According to the author, the said changes in the education system did not bring about an explosion of religiousness among the school learners, so the present state of things turned out to be rather a manifestation of the church gaining formal influence and the state authorities’ submission rather than an evangelical success.

Besides, studies conducted in the first 5 years after introducing religion in schools, already showed that certain non-religious motivations in taking up RE, tended to prevail. There were often related to pragmatic and conformist attitudes. The influence of the family and the pro-religious climate at schools were said to be the most prominent factors. Still, the authors were concerned by the fact that every one in four students declare that non-attending RE and the subsequent lack of grades may result in troubles, which, according to the authors, proves that there exists a cultural climate in Poland that will only strengthen the conformist attitudes towards RE classes.[12] And, as may be noted, their prognosis was correct.

The Catholic priests also see certain difficulties inherent in catechesis being taught in school. Attention is being paid (Tułowiecki 2010: p. 125-127) to the weakening bond between the children and the parish and moving the religious relations from the ecclesiastical organization to the school’s grounds as well as different relations with the parents who expect to treat religion as the provision of a certain service, without making any contribution to their children’s religious upbringing. The priest formulating these opinions also views the collision between the religious reality and the reality of a dynamic youth environment within the confines of a single institution, which performs both educational and pedagogical functions, as a threat. The author writes, for example about the confrontation with modern pluralism and postmodernism in the atmosphere of axiological turmoil.

It thus can be noted that almost 30 years’ practice of teaching RE in the Polish schools has brought about a particular social situation becoming established and strengthened, but it did not eliminate all the conflicts, which, considering their nature, seems impossible.

A major threat related to the common presentation of a single worldview, especially using the authority of the state leads to the unification of attitudes and worldviews, which tends to inhibit creativity and reduce the cultural wealth of this society. The opportunism of public powers and readiness to comply with the demands of the church officials contribute to the discrimination of non-believers. Since the fundamental principles of democracy are the principle of equality and the principle of the state as the common good of all its citizens, public schools should be neutral with regard to worldviews.

References

Agnosiewicz M., Wprowadzenie religii do szkół, 2002, http://www.racjonalista.pl/kk.php/s,434

Bartnik C. S., „Słowo”, 3 VI 1993, cyt za: Agnosiewicz M., Wprowadzenie religii do szkół, 2002, http://www.racjonalista.pl/kk.php/s,434

Dostępność lekcji religii wyznań mniejszościowych i lekcji etyki w ramach systemu edukacji szkolnej. Analiza i zalecenia 2015, Biuletyn Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich, Zasada Równego Traktowania Prawo I Praktyka Nr 17.

Kuroń J., Żakowski J. (1997), Siedmiolatka czyli kto ukradł Polskę?,Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie.

Mill J. S. 2012, Utylitaryzm. O wolności, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo naukowe PWN

Noelle-Neuman E., 1974 , The Spiral of Silence: A Theory of Public Opinion, Journal of Communication, vol. 24, nr.3, p. 43-51

Olszewski B.(2010), Konflikt strukturalny na przykładzie nauczania religii w szkołachin: M. Tabernacka, R. Raszewska-Skałecka (red.) Płaszczyzny konfliktów w administracji publicznej, Warszawa, Wolters Kluwer

Paprzycki J., 2015, Prawna ochrona wolności sumienia i wyznania, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo C.H.Beck

Słowik K. Beczek. W. (2015), Religię wprowadzono do szkół tylnymi drzwiami i na szybko. “Miałem telefony z episkopatu”.http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114871,18941898,religie-wprowadzono-do-szkol-tylnymi-drzwiami-i-na-szybko-mialem.html

Tułowiecki D., 2010, Dwadzieścia lat religii w szkole – nadzieje, trudności, wyzwania. Próba refleksji socjologicznej, in K. R. Kotowski, D. Dziekoński (red.) Dwadzieścia lat katechezy w szkole, Warszawa-Łomża, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego w Warszawie

Tyrała R., 2014, Bez Boga na co dzień. Socjologia ateizmu i niewiary, Kraków, NOMOS

Wilkinson, K. Pickett, 2011, Duch równości. Tam gdzie panuje równość wszystkim żyje się lepiej, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo Czarna Owca

Wiśniewska K., Religia na maturze możliwa w 2021 r.? Kościół dogadał się z rządem Beaty Szydło,2016, http://wyborcza.pl/1,75398,20126283,religia-na-maturze-mozliwa-w-2021-r-kosciol-dogadal-sie-z.html?disableRedirects=true

Authentic sources of opinions

Niesiołowski i Grodzka o religii. “Szkoła od edukacji, Kościół od katechezy” czy “im więcej religii tym lepiej”?, http://www.tvn24.pl)https://www.tvn24.pl/wiadomosci-z-kraju,3/niesiolowski-i-grodzka-o-religii-szkola-od-edukacji-kosciol-od-katechezy-czy-im-wiecej-religii-tym-lepiej,394666.html

Społeczna kampania „Szkoła to nie kościół”

OŚWIADCZENIE, ŻE DZIECKO NIE BĘDZIE UCZĘSZCZAŁO NA RELIGIĘ WE WNIOSKU O PRZYJĘCIE DO SZKOŁY – INTERWENCJA FUNDACJI, https://wolnoscodreligii.pl/wp/oswiadczenie-ze-dziecko-bedzie-uczeszczalo-religie-we-wniosku-o-przyjecie-szkoly-interwencja-fundacji-2/

http://rownoscwszkole.pl/o-projekcie

Religia w szkołach? “Chcemy, żeby płacił za to Kościół” http://www.tvn24.pl/wiadomosci-z-kraju,3/spor-o-finansowanie-z-budzetu-panstwa-lekcji-religii-w-szkolach,526692.html

http://wolnoscodreligii.pl/wp/kampania_spoleczna_szkola_to_nie_kosciol/

Statistics and study reports

Opinie o nauczaniu religii. Komunikat z badań. Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, BS/119/2007, Warszawa, lipiec 2007 (CBOSBS/119/2007) http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2007/K_119_07.PDF

Religia i kościół w przestrzeni publicznej. Raport z badań. Warszawa, grudzień 2013 (CBOS BS/170/2013)

file:///C:/Users/IM/Documents/Konferencje%20wystąpienia/Religia%20w%20szkole%20lub%20poza%20szkołą/Reigia%20i%20kościół%20w%20przestrzeni%20publicznej%202013.PDF

Religia w systemie edukacji. Komunikat z badań, Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej, BS/136/2008. Warszawa, wrzesień 2008 (CBOS BS/136/2008)

http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2008/K_136_08.PDF

Respektowanie wolności sumienia i wyznania w szkole publicznej Raport. Stowarzyszenie na rzecz Państwa Neutralnego Światopoglądowo NEUTRUM 1996, Warszawa

Struktura administracyjna Kościoła katolickiego w Polsce i podstawowe statystyki. GŁÓWNY URZĄD STATYSTYCZNY. Notatka informacyjna opracowana wspólnie z Instytutem Statystyki Kościoła Katolickiego SAC, Warszawa 2017, file:///C:/Users/IM/Downloads/struktura_administracyjna_kosciola_katolickiego_w_polsce%20(1).pdf

Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski. Narodowy spis powszechny ludności i mieszkań 2011, Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Warszawa 2015, file:///C:/Users/IM/Downloads/struktura_narodowo-etniczna.pdf

Endnotes

1 20 years of religion in schools, http://fakty.interia.pl/religia/news-20-lat-lekcji-religii-w-szkolach,nId,886445

2 Ibidem.

3 file:///C:/Users/IM/Downloads/struktura_narodowo-etniczna.pdf

4 http://wolnoscodreligii.pl/wp/kampania_spoleczna_szkola_to_nie_kosciol/

5 http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2007/K_119_07.PDF

6 OŚWIADCZENIE, ŻE DZIECKO NIE BĘDZIE UCZĘSZCZAŁO NA RELIGIĘ WE WNIOSKU O PRZYJĘCIE DO SZKOŁY – INTERWENCJA FUNDACJI,https://wolnoscodreligii.pl/wp/oswiadczenie-ze-dziecko-bedzie-uczeszczalo-religie-we-wniosku-o-przyjecie-szkoly-interwencja-fundacji-2/

7 http://rownoscwszkole.pl/o-projekcie

8 http://www.tvn24.pl/wiadomosci-z-kraju,3/spor-o-finansowanie-z-budzetu-panstwa-lekcji-religii-w-szkolach,526692.html

9 http://rownoscwszkole.pl/o-projekcie

10 Respektowanie wolności sumienia i wyznania w szkole publicznej Raport. Stowarzyszenie na rzecz Państwa Neutralnego Światopoglądowo NEUTRUM 1996, Warszawa, p. 9-16.

11 Ibidem, p. 18.

12 Respektowanie wolności sumienia i wyznania w szkole publicznej Raport., p. 13.