Introduction[1], [2]

The Russian attack on Ukraine on 24th February 2022 sent shock-waves throughout Europe. The violence and occupation since that date have led to human, economic and cultural devastation, over 6 million refugees from an original population of around 41 million and another 6 million internally displaced persons.[3] Addressing the human suffering from this war must always be the first concern.

The sudden geopolitical shift that has followed the rightful condemnation of Russia’s conduct requires many seasoned academics, including the present author, to reconsider certain assumptions in their disciplines and reassess the viability of established pathways for cooperation and negotiation over differences. International lawyers, especially those of the liberal school of international law that believe in institutional cooperation for mutual benefit (in contrast to realist accounts of zero-sum games), must explain how and why international law still constrains the conduct of powerful States in a meaningful way.

Every war has its own unique and terrible features. But the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022 presents a challenge to the international legal order that has not been seen since 1945. Although Russia’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014 was equally unlawful, it was a more constrained mission to gain territory; it was not an attempt to eliminate an entire nation. Other States responded to Russia’s conduct at that time with sanctions (countermeasures) but cooperation on Arctic and Antarctic affairs mostly continued.[4] Other violations of the most fundamental norm of the post-war international order – the prohibition on the use of force[5] – have also been more limited in scope and ambition.[6]

The article which follows examines the discipline of polar law[7] in the shadow of the Russian aggression which has threatened more than thirty years of gradual trust-building and collaboration in human rights, Indigenous rights, scientific research, environmental protection and economics. It shows that while many fora for cooperation with Russia in the polar regions are suspended or diminished either formally or de facto, legal solutions to challenges and disputes still have a critical role to play – and are in fact supported by the Russian Federation. Differences regarding interpretation or perceived gaps in legal regulation in the polar regions have not changed significantly following the Russian conduct and they require legal experts (amongst others) to negotiate solutions.

The article begins with a discussion of the resilience of international law in general before addressing the problems that the Russian aggression poses in the field of polar law. Specific attention is then paid to the Arctic Council, legal mechanisms for cooperation in the Arctic, the Antarctic Treaty System and other legal regimes of importance in the polar regions. The focus in the article is primarily on public international law but private law is also important in the polar regions, even if this area has not been well covered in past academic literature under the polar law banner.[8] Private law is, however, beyond the scope of the current article.

The article demonstrates that the Russian Federation, notwithstanding its illegal conduct in Ukraine, is committed to legal solutions in important Arctic and Antarctic fora. Legal approaches to challenges and disputes in the polar regions remain of critical importance.

International Law is Resilient

Although the geopolitical context in which polar law operates is fundamentally altered by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the basic fabric of the legal order remains unchanged. In other words, the law is the same; the conditions are different. This might seem at once both self-evident and naive but is worth restating for the legal sceptics who point to one egregious breach and declare the whole system deceased. A simple analogy from domestic law will hopefully suffice to quieten those anxious that international law is finished, impotent or irrelevant since a powerful country can breach its most basic norm and remain in breach for over a year – indeed, over nine years when considering the occupation of Crimea.

The prohibition of murder is probably the most important norm of criminal law. The ability of individuals and families to go about their daily life and make plans for the future pivots upon it. Most people refrain from murder not because they are dissuaded by a possible sanction (in contrast to, e.g., parking or speeding offences) but because they have no particular incentive or passion to kill another. Nevertheless, sometimes there are murders. Extraneous circumstances such as the quality of governance, availability of weapons, demographics, poverty and economic inequality make these more or less frequent.

The response to cases of murder, even the most horrific – or perhaps especially the most horrific – is not to declare the futility of the criminal law and give up on it entirely. John’s having killed Martin yesterday is no defence to Jane’s killing of Fatima tomorrow. Furthermore, it is no justification for Jane’s stealing of Fatima’s car, driving it dangerously while texting on her phone and later parking in the spot reserved for the university rector (assuming Jane is not, in fact, the university rector).

International law, like criminal law, contract law, family law and administrative law, works most of the time; but is only noticeable in the breach. A breach of law, even an egregious breach of the most fundamental law, is not the end of law but the opportunity for law to show itself in the institutional reactions.

A more sophisticated account of the ongoing application of international law is presented in the International Law Commission Articles on State Responsibility which remind us:

The legal consequences of an internationally wrongful act under this Part do not affect the continued duty of the responsible State to perform the obligation breached.[9]

The State in breach must both cease its wrongful conduct and uphold its original obligation[10] – in the case of the Russia Federation, cease all acts of aggression in Ukraine and return all territory within the 2014 borders to Ukraine.

Other States are in certain circumstances entitled to suspend carefully selected obligations vis á vis the State in breach (countermeasures or measures[11]) and even to terminate treaties with the offending party,[12] but all this happens not in the absence of international law but specifically according to international law. The fundamental norms of international law (known in law as norms of ius cogens or peremptory norms) can never be suspended or terminated in response to the wrongful conduct of another State.[13]

While there are calls for suspension of political and scientific cooperation with the Russian Federation, no State is seeking the suspension of law. The States calling for the defence of Ukraine are instead demanding that international law be upheld, now more than ever. Although the UN Security Council is paralysed by the Russian veto (as it has been stymied in the past by Chinese, American and French vetoes), the General Assembly, the International Court of Justice, the International Criminal Court, the European Union, the European Court of Human Rights and dozens of individual States have swung into action with resolutions, rulings and countermeasures. Furthermore, as shall be shown below, in other important fora of importance to the polar regions, the Russian Federation is still following international law and international legal procedures to manage its interests and has even made (spurious and unsustainable) claims that its actions in Ukraine are legally justified.[14]

The Immediate Challenges to Polar Law

In 2023, Tanaka, Johnstone and Ulfbeck defined polar law according to three criteria: spatial scope (the polar regions); material scope (international, regional and domestic law); and temporal scope (polar law is constantly evolving).[15] They likewise identified three functions of polar law: coordination, cooperation and economic.[16] Polar law contains two distinct fields: law pertaining to the Antarctic and law pertaining to the Arctic; but common features identified by Tanaka, Johnstone and Ulfbeck include emphasis on environmental protection; scientific research; peaceful use; and international cooperation.[17] All of these features, which are intertwined, are challenged by Russia’s conduct and the obligations of all other States to respond in defence of the territorial integrity of Ukraine.[18]

The threat to peaceful use might be the most obvious although it is probably the least immediate of the above. It has become difficult to trust that the territorially largest Arctic State and original party to the Antarctic Treaty will respect the prohibition on the use of force to settle disputes. Its neighbours are seeking shelter in new ways (for example, the swift applications of Finland and Sweden to NATO membership) but there is no indication that Russia will use force in the polar regions per se. However, political, scientific and environmental cooperation have all been undermined.

The most visible suspension of international cooperation is in the work of the Arctic Council. This includes dozens of projects involving Russia’s vast Arctic, including environmental monitoring and disaster-prevention and preparedness activities. Beyond the Arctic Council itself, the sanctions-regimes imposed in response to the Russian aggression have thwarted dozens of international scientific projects as it is no longer possible to pay salaries and expenses from Western institutions to Russian scientists, to obtain visas for fieldwork or in-person meetings and to transfer equipment across borders. This affects environmental as well as educational and economic projects. The 2017 Arctic Science Agreement was designed precisely to simplify these processes. How it will be interpreted and applied in the event of a Russian scientist making an application to conduct research in the West or vice versa has yet to be seen.[19]

The forty-fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM) took place in Berlin in May and June 2022 amidst a great deal of disquiet and the forty-fifth ATCM was held in Helsinki in June 2023.[20] The system is ultimately functioning about as well as normal which is to say slowly and at the great frustration of those who would like to see stronger measures to protect the seventh continent.

Non-State cooperation remains increasingly difficult, not least in the academic sector that is critical to the development of new insights to manage the regions peacefully and equitably. On 4th March 2022, the Russian Union of Rectors, on behalf of over 300 Russian universities, issued a statement supporting the Russian attack and the Putin government. It called for Russian universities ‘to conduct a continuous educational process, to instil patriotism in young people, the desire to help the Motherland’ as the ‘main duty’ of Russian universities.[21] On the same day, the Duma passed a law to criminalise any critique of the war in Ukraine with a potential jail sentence of up to fifteen years for anyone who called the war a war.[22] If partner universities were wavering on whether they could continue direct cooperation, the statement made it clear that academic freedom in Russia was over (temporarily, one hopes) and that Russian-based researchers would face personal risk were they to acknowledge the realities of the situation. The Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavík and the Arctic Frontiers Conference in Tromsø, interdisciplinary conferences that attract diplomatic, Indigenous, academic and business representatives, have gone ahead with very limited Russian participation.

The Arctic Council

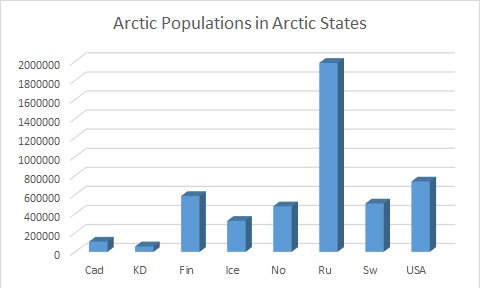

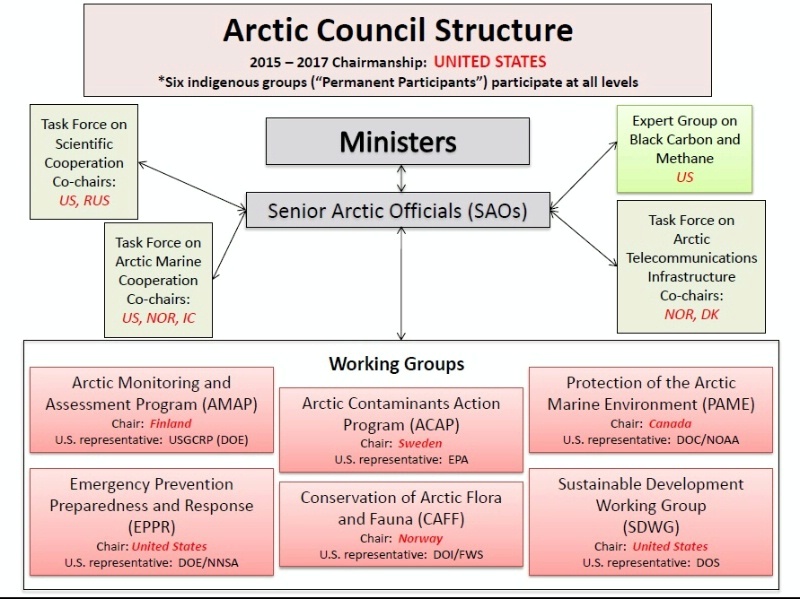

Iceland concluded its chairship of the Arctic Council in 2021 with a celebration of the 25th anniversary of the forum before handing the chairship over to the Russian Federation. But pan-Arctic cooperation goes back to the late 1980s – indeed, it can be traced to the Reagan-Gorbachev Reykjavík Summit in 1986. Only a year later, Gorbachev called for cooperation on six themes: resource development; science; Indigenous Peoples; environmental protection; and – perhaps most striking today – a nuclear-weapons free zone; and restrictions on naval activities.[23] This led to the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy in 1991, to which the Arctic Council, founded in 1996, is a direct successor.[24]

On 3rd March 2022, the Arctic Council came to an abrupt halt as the seven western State members of the Arctic Council, in response to the invasion of Ukraine, ‘temporarily paused participation in all meetings of the council and its subsidiary bodies.’ They did, however, ‘remain convinced of the enduring value of the Arctic Council for circumpolar cooperation and reiterate[d] support for this institution and its work.’ They added, ‘We hold a responsibility to the people of the Arctic, including the indigenous peoples, who contribute to and benefit from the important work undertaken in the Council.’[25]

On 8th June 2022, the seven States declared a tentative resumption of some Arctic Council work on some projects that had been approved at the Reykjavík ministerial meeting in 2021, just before the chairship passed to Russia. Around 60-70 projects have resumed, out of a total of 130 – none of which involve Russian partners, territory or maritime zones.[26] Importantly, Russia has not withdrawn from the Arctic Council, nor has it objected to the limited activities of the other seven States under the Arctic Council banner. This indicates that it is not ready to abandon the Arctic Council infrastructure completely and that the other State members do not wish its expulsion (which would, in effect, dismember the Arctic Council entirely).

Amidst some geopolitical jitters, a low-profile, online only Arctic Council ministerial was held in May 2023 in which the chairship passed formally from Russia to Norway. Unsurprisingly, in the absence of any political negotiations for over twelve months, no Arctic Council Declaration was agreed, as is the norm at the highest-level, biennial event. Rather, a bland statement was issued with the quiet acceptance of all Arctic States.[27] The statement steers clear of commitments but recognises the ‘valuable work accomplished by the Arctic Council since the last Ministerial meeting’ and approves the ongoing work of the Council, including funding for the Arctic Council Secretariat and the Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat through 2025.[28] The very fact that all eight States agreed this statement indicates a will for the revival of the Arctic Council. The chairs and secretariats of the six working groups and the Expert Group on Black Carbon, the Arctic Council Secretariat and the Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat met the Norwegian Chair of the Senior Arctic Officials in Tromsø in June 2023 to examine how they might resume their activities, ‘supported by all eight Arctic States and six permanent participants.’[29]

But caution is required. On 21st February 2023, Russia released a revised Arctic policy paper in which it had replaced a reference to ‘cooperation within the Arctic Council’ with a new focus on ‘development of relations with foreign states on a bilateral basis… taking into account the national interests of the Russian Federation in the Arctic.’[30] This indicates that Russia will only turn to the Arctic Council to the extent that this is in its own interests. Otherwise, it will prioritise relations – economic, environmental and political – with States that are prepared to tolerate its conduct in Ukraine.

Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic were amongst the first to reach out across Cold War frontiers and their cross-border populations (bearing in mind that State frontiers were built across their territories). They may provide once again the impetus to rebuild trust in due course. Three of the cross-border Indigenous Permanent Participant organisations at the Arctic Council contain Russian members (Aleut International Association (AIA), Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) and Saami Council (SC). Another, the Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), represents forty Indigenous Peoples within the Russian Federation. This, especially in the light of the criminalisation of dissent in Russia, puts them all in extremely difficult positions. RAIPON, already emasculated following a temporary suspension and reestablishment under a new president favoured by the Putin government,[31] issued a statement in support of the Russian attacks on Ukraine.[32] However, other representatives of Indigenous Peoples in Russia have spoken out against the war.[33] ICC and SC have avoided direct condemnation of the war in Ukraine and called for cooperation to continue through the Arctic Council.[34] Nevertheless, SC has stopped its Russian members from taking part in its activities while expressing regret for their exclusion which it attributes directly to the war.[35] Some permanent participant representatives have expressed frustration at being sidelined by the State members of the Arctic Council in responding to the situation, being ‘informed’ of steps but not consulted in contrast to their habitual and structurally in-built participation at Arctic Council meetings themselves.[36]

The Arctic Council lives on – but it remains seriously weakened. Even if Russia retreats from Ukraine tomorrow, the trust and spirit of partnership that has been cultivated cautiously since Gorbachev’s historic speech at Murmansk in 1987 may take a similarly long time to rebuild. Regional cooperation through the Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC), the Northern Dimension policy of the EU, Iceland, Norway and Russia, and the Council of Baltic Sea States (CBSS) looks more vulnerable. BEAC’s work involving Russia is paused following a declaration by the Nordic countries and the EU that they would ‘suspend activities involving Russia’ and all projects involving Russia or Belarus under the Northern Dimension are likewise suspended.[37] Russia’s retort to ‘these clearly unfriendly steps’ was that ‘without Russia, the existence of these bodies loses meaning.’[38] Ten State members and the High Representative of the European Commission effectively suspended Russia (and observer Belarus) from the forum’s ‘proceedings, work and projects’ to which Russia responded by declaring its withdrawal.[39]

International Law in the Arctic

Yet the Arctic Council is not the be all and end all of polar law. In fact, pedantically speaking, very little of what it does is law at all. At a purely academic level, the weakness of the Arctic Council may actually prove a blessing in disguise by forcing scholars, diplomats and advocates to move away from an over-emphasis on the Arctic Council as the fulcrum of Arctic cooperation and examine more closely and systematically other fora. This is particularly important in the legal arena which Koivurova and Shibata have argued is more resilient than ‘soft’ institutional cooperation.[40]

The Russian Federation, whilst in flagrant breach of the prohibition of the use of force, is quietly following international law and legal process in the polar regions. Unsurprisingly – ‘country following the law’ does not garner any more international headlines than ‘person does not commit murder’. A couple of illustrations should suffice to illustrate the point but more can be found in recent publications by Koivurova and Shibata,[41] and Koivurova and others.[42] These include reflections on the Svalbard Treaty, the Polar Bear Agreement and regional fisheries organisations.

The Delineation of the Continental Shelf

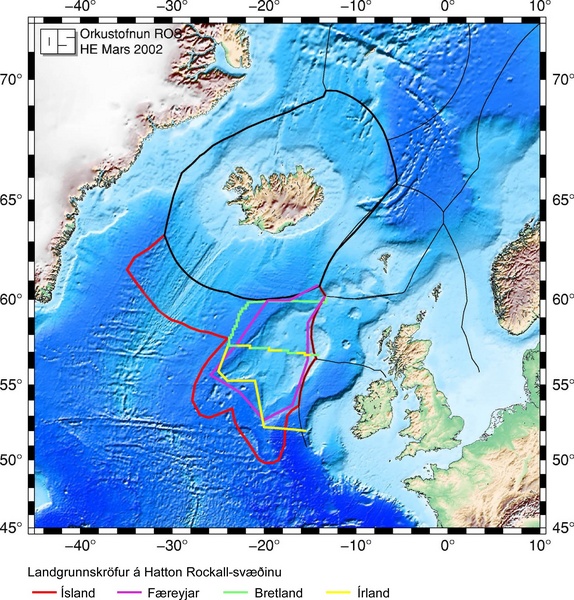

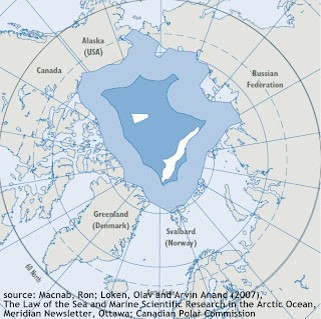

The UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) reviews State submissions on the extent of States’ continental shelves.[43] The CLCS distinguishes between the sections of the ocean floor over which States have exclusive resource rights (the continental shelf) and the bits left over which are common heritage of humankind (known in international law as the Area beyond national jurisdiction).[44] It does not adjudicate between overlapping submissions by different States. Its role, in part, is to protect the common heritage against overzealous submissions by States but not to intervene in disputes over the boundary lines between States.

On 6th February 2023, the CLCS accepted most of Russia’s data indicating which parts of the ocean floor were continental shelf and hence not common heritage of mankind. It did not (nor should it nor would it) determine which pertained to Russia, Greenland/Denmark or Canada. However, the CLCS (following the recommendations of the sub-Commission) found that there was insufficient evidence to support the Russian submission regarding one part – the Gakkel Ridge.[45]

Russia responded with a revised submission to the CLCS just ten days later[46] – suggesting that they anticipated the response of the CLCS and had a revised map and data already prepared. In the new submission, Russia implicitly accepted the advice from the CLCS, i.e., that the Gakkel Ridge does not constitute a part of the continental shelf and hence neither Russia nor any other State has exclusive rights to its resources.

This is an example of Russia abiding by both legal process and conclusions, where the legal result does not match Russia’s ambitions.

Arctic Ocean Fisheries

Russia – and other parties that have taken what can most generously be described as an ambiguous stance on Russian aggression – are likewise moving forward, albeit slowly, under the most recent (non-)fisheries agreement, the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement (CAOFA).[47] The agreement came into force in 2021. It prohibits any commercial fishing in the High Seas area of the Central Arctic Ocean and calls for a cooperative scientific programme to identify the potential for sustainable fisheries in the zone. Commercial fisheries may only be established if the science shows that they can be managed sustainably and a regional fisheries management organisation is established for this purpose. There are ten parties: the United States, Canada, Kingdom of Denmark, Norway, Russia, Iceland, China, Japan, South Korea and the European Union (which represents Finland, Sweden and all other EU member States). Online meetings of the provisional scientific coordinating group (PSCG) were held in May and September 2022 and the first conference of the parties (COP) was held in South Korea in November.[48] Not only did all the parties send a delegation, they were able to agree by consensus the rules of procedure for the COP going forward as well as the mandate for the PSCG (tasked with developing a joint programme on scientific research and monitoring).[49] (A second COP was held in South Korea in June 2023 but the proceedings were not available at the time of writing.) Two observers were admitted to the first COP (the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and the World Wildlife Fund for Nature Arctic Programme).[50] The CAOFA requires the integration of Indigenous and local knowledge in the scientific research and any decisions regarding the opening of fisheries operations[51] but Indigenous organisations are not parties to the CAOFA itself (a privilege extended only to select States and the European Union) and were represented at the meeting only through national delegations.[52]

The research programme is likely to be slow-moving and hindered in practice by the barriers to cooperation with the Russian Federation at this time. Russia is unlikely to permit marine scientific research in its EEZ (bordering on the Central Arctic Ocean and containing many of the stocks that might straddle the High Seas in due course) by States loudly protesting the war in Ukraine (whether under the CAOFA structures or otherwise). Meanwhile, Russian scientific programmes are unlikely to be able to work with partners in the EEZs of the other four littoral States.

The consequences, however, of inaction or sluggishness on the scientific programme are that commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean remains even more unlikely, until at least, 2036. It was never in the interest of Russia or the other four littoral States to promote science that might identify the feasibility of commercial fishing in the zone as any stocks therein will straddle the EEZ of the littoral States.[53] To put it simply, any fish taken in the Arctic High Seas are fish that cannot be taken in the EEZ. On this, Russia’s interests align with the US, Canada, Norway and Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) and are opposed to those of the other five parties who have no neighbouring EEZ and hence no (potentially) straddling stocks.

The ‘Arctic Council’ Treaties

Three treaties were agreed under the auspices of the Arctic Council but are formally independent of it.[54] The parties to each are exclusively the eight Arctic States. They cover Search and Rescue, Emergency Oil Spill Preparedness and Response, and Arctic Science.[55] While these treaties remain in force, there is little or no activity under them. All three remain difficult to implement as they depend on the functioning of the Arctic Council, especially the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group, and related institutions such as the Arctic Coast Guard Forum.[56] The first two treaties create very little law (beyond which already exists in global treaties and international customary law[57]) but rather open the door to cooperation and practice exercises – which cannot take place without political cooperation and trust between military and coastguard teams on the frontline of rescue and oil-spill emergency responses. The Chair of the Arctic Council acts as convenor for the Arctic Science Agreement but it is understood that no requests for research access under the agreement had been received following the Russian invasion up to the transfer of the chairship to Norway in May 2023.[58]

The Rights of Indigenous Peoples and Decolonisation

Russia aside, the Western Arctic States have no shortage of legal issues to address, especially regarding their treatment of Indigenous Peoples. These examples are not intended to justify any form of whataboutery – that ‘the West’ so-called is also breaking international law so should not criticise Russia for its violations in Ukraine. Russia’s own Indigenous Peoples, including over forty national groups, are hardly better off and may indeed be literally at the frontline of the war.[59] Rather, these cases are a timely reminder that there is plenty work still to be done in polar law without Russian cooperation.

On 1st February 2019, the UN Human Rights Committee concluded that Finland was in breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights owing to its interference in the electoral roll for the Sámi Parliament in Finland.[60] Four years have now passed and the government’s latest attempt to revise the law, in February 2023, could not even get out of the parliamentary committee stage.[61]

Norway’s own Supreme Court declared the massive windfarm at Fosen unlawful on 21st October 2021 on the basis of the same convention.[62] Nevertheless, at the time of writing, the turbines still turn, cutting across Sápmi – the Saami homeland – disrupting the migrating reindeer and unlawfully interfering with Saami rights to their land and culture. The longer the windfarm operates, the harder it becomes for Saami to bring their herds back to the area and the larger the profits of the operator.[63]

Next door in Sweden, the Girjas Sami also won their court battle in 2020 when the Supreme Court declared that the Girjas Sami Village had exclusive rights to issue licences for hunting and fishing in their historic territory and that the Swedish State had no authority in this area.[64] In what appears a quite distinct area of law but in fact pivots on very similar questions around Indigenous sovereignty, the US Supreme Court in June 2023 upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act against a challenge from non-Indigenous parents, the State of Texas and a law firm working pro bono that is better known for representing oil firms.[65] The Act protects native Alaskan and American Indian children. The precedent is an important indication of the Supreme Court’s reluctance to interfere with tribal sovereignty though nothing can be taken for granted as the case pivots, in part, on the standing of the plaintiffs.

While all these cases are technical legal ‘wins,’ one is reminded of President Jackson’s famous remark (quite possibly fictional) on another case in which native American rights were upheld: ‘John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.’[66] The Trail of Tears continued unabated for another eighteen years.

The Greenland Constitutional Commission unveiled a draft Constitution of Greenland in April 2023.[67] Although it will take many rounds of negotiation in numerous fora before such a text can be implemented, if at all, the draft points to yet one more step in Greenland’s decolonisation process. Originally asked in 2017 to prepare two drafts – one to function for Greenland within the Kingdom of Denmark and one in the case of independence as a sovereign State – the commission decided to deliver only on the latter.

Not all decolonisation efforts are strictly legal but a spate of inquiries into colonial history in the Arctic records abuses conducted through law and under the cover of law as well as raising questions about legal remedies. Canada continues to reckon with the findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Report of 2017: to date, of 94 Calls to Action, only 10 have been fully implemented.[68]

A much smaller-scale reconciliation commission in Greenland reported in 2017 and its recommendations were not systematically followed-up or measured.[69] However, three new inquiries are now beginning: on involuntary contraception of Greenlandic women and girls in the 1960s and 1970s; the integration process of 1953; and on Danish post-war policies in Greenland.[70]

Norway’s Commission to Investigate the Norwegianisation Policy and Injustice against the Sámi and Kvens/Norwegian Finns delivered a 758-page report in June 2023.[71] Two commissions are currently underway in Sweden – one regarding Saami and the other on Tornedalians, Kvens and Lantalaiset.[72] Finland has a Truth and Reconciliation Commission Concerning the Sámi People.[73]

The United States has not even begun to reckon with its historic mistreatment of Native Americans and Alaska Natives in a systematic manner though calls for truth and reconciliation in the United States with a mandate to investigate taken native children and attempts to assimilate them in an abusive boarding school system are gaining ground.[74]

These cases, inquiries and outstanding issues do not depend on cooperation with Russian participants. A cooling of Arctic relations or increasing ‘securitisation’ of the discourse on Arctic cooperation must not be deployed as a smokescreen to conceal or deprioritise action on these matters. In short, polar law, including the law of Indigenous Peoples and decolonisation, still has much to do.

The Antarctic Treaty System

Notwithstanding the similarities of extreme (to humans) climate and environmental vulnerability, the legal orders of the polar regions are fundamentally different. In many, if not most respects, the Arctic legally is no different to any other geopolitical space to the extent that its governance is based on State sovereignty and the law of the sea. State sovereignty is being reconceived in new (or perhaps old?[75]) ways with the recognition that Indigenous sovereignty was never extinguished in the Arctic. Indigenous Peoples present similar claims based on the same legal principles in other regions, principally in Latin America.

The Antarctic, by contrast, is legally unique. It is the only terra firma in the world that is not governed according to territorial sovereignty, the claims of the seven claimant States being suspended in 1961 by the Antarctic Treaty which also prohibited the expansion of claims or the making of new claims as long as the treaty remains in force.[76] So far, it has endured for over sixty years.

Calls for an Antarctic-style treaty system in the Arctic in the 2010s were misplaced as they were based on superficial – and sometimes inaccurate – similarities and assumptions, such as that the polar regions were empty of human activity and should remain perpetually so.[77] They were resoundingly rebuffed by the Arctic States and Indigenous organisations who reminded the world of their long presence and leadership in the region.[78] The Antarctic system is not presented here as a model per se for Arctic governance but rather as a reminder that cooperation can withstand hostilities even between the most powerful parties. The Antarctic Treaty was negotiated at the height of the Cold War and agreed in 1959, entering into force two years later. It was not so much agreed despite the Cold War but because of it. The Antarctic Treaty is first and foremost a peace treaty, responding to a fear that the last unpopulated continent would become a playground for weapons testing, military exercises or even hostilities to secure prestigious title. The treaty demands in its first article that:

- Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only. There shall be prohibited, inter alia, any measures of a military nature, such as the establishment of military bases and fortifications, the carrying out of military maneuvers, as well as the testing of any type of weapons.

- The present Treaty shall not prevent the use of military personnel or equipment for scientific research or for any other peaceful purpose.

Two related instruments, the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals and the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources were negotiated in the 1970s and 1980s respectively.[79] These treaties have already withstood a war between two consultative parties – indeed, two States with overlapping territorial claims in the Antarctic – the United Kingdom and Argentina. A fourth treaty, on comprehensive environmental protection, the Madrid Protocol, was agreed in 1991 and came into force in 1998.[80]

If the Arctic Council System is a three-tier system with States, Permanent Participants and Observers, the Antarctic Treaty System is a three-tier system of Consultative Party States, other States Parties and Observers. (There is, of course, no Indigenous population in the Antarctic.) Only the Consultative Parties have decision-making power and they reach agreements, as in the Arctic Council, by consensus, primarily at the annual Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs) and at meetings of the Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Commission).[81]

Unease was evident in the run-up to the 44th ATCM in Berlin, not least because it was unclear whether Russian representatives would be able to secure the necessary visas to enter Germany at all. On this point, the aftermath of Covid-19 provided a face-saving option of virtual attendance. Four Russian representatives joined as ‘virtual audience’ with only three in-person representatives.[82] Meanwhile, Ukraine sent seven in-person delegates and Belarus five.[83]

The Consultative Parties to the ATCM include, as well as the Russian Federation and Ukraine, a number of States that have been more equivocal of Russian aggression in Ukraine, including Brazil, China, India and South Africa. Hence, the Russian Federation is less isolated in this arena. Nevertheless, twenty-five States (of which twenty-three are Consultative Parties) expressed their disapproval by leaving the meeting when the Russian representative took the floor, in an organised expression of support for Ukraine.[84]

The meeting progressed otherwise as anticipated, which is to say that very little of substance was agreed but nor were there any retrogressive steps on, e.g., principles of peaceful use, scientific cooperation and environmental protection.[85] In other words, the consensus-based decision-making system functioned – as much as it ever functions – despite the potential blocking powers of Ukraine, the Russian Federation and their various allies.

The meeting reports from the 45th ATCM in Helsinki, May 2023, have not yet been published but a few factors are notable from the material that is in the public domain at the time of writing. First of all, the virtual attendance option was repeated and around 1/5 of the five-hundred delegates joined online. This has potential not only to make access more equitable vis á vis States with fewer resources (including non-consultative Parties[86]) but may encourage States to send smaller in-person delegations with others joining virtually in order to reduce the climate impacts. Delegation-lists are not yet published from Helsinki but, already in Berlin, the United States included seven virtual audience members to complement fifteen in-person attendees.

The big news from the Finnish ATCM is the agreement of the historic Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic.[87] The declaration emphasises science cooperation and science communication regarding climate change in Antarctica.[88] Although non-binding, it is significant that this declaration was reached at all, just four years after the Arctic Council failed to reach a declaration on anything because of US refusal to acknowledge climate change science.[89]

Tucked in at the end of the declaration is firm recommitment to the mining ban. The Consultative Parties and Members of the Committee on Environmental Protection:

Reaffirm our commitment to Article 7 of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, and stress that Antarctic mineral resource activities other than scientific research, including the extraction of fossil fuels, remains prohibited, in accordance with the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, which does not have an expiry date.

The moratorium on mineral activities in the Antarctic is a robust provision of the Madrid Protocol that is, as indicated in the declaration, not time limited. It can be reviewed in 2048 at the request of one of the Consultative Parties but can only be lifted once a binding legal regime for mining activities has been negotiated. To come into force, any amendment to Article 7 requires a rigorous two-step process. First of all, the revision must have the support of three-quarters of the twenty-six Consultative Parties which held that status at the time the protocol was adopted, i.e., in 1991. Thereafter, the modification must be ratified by all of these twenty-six States as well as three-quarters of all Consultative Parties at the date of the modification.[90] The prohibition on mining in the Antarctic also has wider support from the United Nations General Assembly.[91]

Some have expressed concern that Russian scientific research activities on minerals in the Antarctic have crossed the threshold into (prohibited) prospecting though other State Parties have not made any formal protest.[92] The Russian Federation has (at least) acquiesced to the inclusion of this paragraph but the Consultative Parties may need to take a more pro-active approach to ensure that all parties respect the moratorium.

The Helsinki meeting also agreed that a long overdue framework on Antarctic tourism be developed and this is a key item for the 2024 meeting in India.[93] The devil remains, as always, in the detail and a framework does not necessarily mean that regulations on Antarctic tourism will become stricter.[94] Up until now, tourism in the Antarctic has been limited, not least through self-regulation by the operators themselves and by the refusal of any of the Parties to establish accommodation for tourists on the continent itself. However, numbers are rising rapidly and there is always a risk of new operators entering the market who do not follow the voluntary guidelines.[95]

Despite the difficulties presented by Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the aforementioned examples indicate that the parties are keen to see the Antarctic Treaty System operate in a relatively normal way – with all the limitations that ‘normal’ Antarctic governance implies.

However, on one important matter, the treaty provisions were ostensibly set to one side. Belarus and Canada both sought consultative party status. According to Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty, parties are entitled to consultative status either by virtue of being an original party (twelve, including the seven claimant States) or ‘during such time as that Contracting Party demonstrates its interest in Antarctica by conducting substantial scientific research activity there, such as the establishment of a scientific station or the despatch of a scientific expedition.’[96] Canada acceded to the Antarctic Treaty in 1998 and Belarus in 2006; they have since both conducted relevant scientific research activities on the continent. There are no additional requirements. Nevertheless, admission to the elite group requires consensus of existing Consultative Parties, including Ukraine (party since 1992 and Consultative Party since 2004). At the Helsinki meeting, Ukraine blocked Belarus’ application and Canada responded by postponing its application to 2024, anticipating that it would be vetoed by Russia and/or others in response.[97] Ukraine’s position, while eminently understandable, creates problems for the other parties who wish to see the Antarctic Treaty System continue relatively untroubled by the war in Ukraine.[98] If a precedent is set according to which any existing Consultative Party can block acceptance of a new State at the decision-making table, it politicises a longstanding arena of cooperation that has so far been isolated from the kind of political jostling that routinely troubles applications for membership of the United Nations. Furthermore, it creates yet another level of gatekeeping to Antarctic decision-making in addition to the already onerous requirement of breathtakingly expensive scientific research.[99]

Just a month after the Helsinki meeting, the CAMLR Commission held a special meeting in Santiago, Chile to discuss marine protected areas (MPAs) in the Antarctic.[100] The membership of the CAMLR Convention does not coincide perfectly with the ATS membership as not all Antarctic Treaty parties (consultative and otherwise) are members of CAMLR and the latter includes a number of States and the European Union with interests in fisheries in the Southern Ocean that are not Antarctic Treaty parties. The CAMLR Commission operates, amongst other things, as a regional fisheries management organisation for the Southern Ocean and in this respect, it plays a critical role in collating scientific data and regulating fisheries, including quota allocations. The CAMLR Commission also operates on a consensus basis, meaning that any single State Party can block agreement. Nowhere are the tensions between States prioritising environmental protection and those of a more extractive bent more apparent than in the negotiations of MPAs in the Southern Ocean. The environmental champions chalked up a significant win in 2016 with the agreement of a huge MPA in the Ross Sea but attempts to create additional MPAs are repeatedly thwarted.[101] China, usually followed by Russia, repeatedly rejects new MPAs under the cover of ‘science-based’ decision-making – insisting that no restrictions should be introduced until there is sufficient scientific evidence to prove their necessity in a rejection of a precautionary approach.[102] At the 2023 meeting, China and Russia once more blocked the creation of new MPAs, calling instead for more scientific research. Their position is longstanding and has no evident connection to Russia’s isolation over its conduct in Ukraine.[103]

The Antarctic Treaty System has proven resilient for six decades; its founding principles of peace and science are not facing any present danger, notwithstanding the armed attack of one Consultative Party on another. The original treaty precedes by over a decade the first global conference on the environment and the ‘birth’ of international environmental law as a discipline.[104] Innovations honed in the Antarctic such as environmental impact assessments and steps to reduce illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing have informed global practices.[105] The system faces many challenges adapting to pressures from increasing tourism, climate change, risks of over-fishing and IUU fishing, as well as the environmental footprint of the scientific expeditions so privileged under the treaty. Protected by both a geographic and geopolitical distance, the attack on Ukraine has not to date had a significant impact on the legal systems of the Antarctic, even if it has generated a distinct diplomatic chill.

Other key fora and instruments on polar law

Much of the law that governs the polar regions is global in nature but with regional effect. The Russian Federation remains governed by and an active participant in these institutions as it has through years of increasing tensions since its unlawful annexation of Crimea. The climate change framework and the law of the sea are the most obvious categories in this regard but so too are basic norms of sovereignty, human rights and trade law in the Arctic as well as environmental law at both Poles. Global instruments and fora govern polar shipping, use of resources on the deep seabed, MPAs and search and rescue. The Polar Code that applies to most commercial shipping (though not smaller cargo, fisheries or smaller tourist vessels) is a work in progress. Katsivela identifies a number of areas that require strengthening if the safety of seafarers and the vulnerable polar environment are to be adequately protected, including expansion of scope to cover other vessels, safety equipment, seafarer training, use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic, black carbon emissions, noise pollution and biofouling.[106] This can only be achieved through negotiations at the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO has, since 2019, been an observer at the Arctic Council and has been invited to send experts to ATCM meetings.[107] Neither the Arctic Council nor the ATCM have legal personality so neither can be represented in their own right at the IMO though of course the State members are all represented. However, ICC has been attending the IMO meetings for years and in November 2021 was granted provisional consultative status, in recognition of the importance of Inuit expertise in decision-making about shipping in their territories.[108] The Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition (ASOC), an NGO observer to the ATCM, also attends IMO meetings (through the Friends of the Earth International delegation) to lobby for shipping regulation in the Southern Ocean.[109] More general measures through the IMO to reduce carbon emissions from shipping (not currently included in the Paris Agreement targets[110]) could slow the rapid warming at the Poles.[111]

The milestone Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), an implementing agreement under UNCLOS, provides for equitable use of marine genetic resources, area based management tools (including MPAs), environmental impact assessments, and capacity building and transfer of technology to developing countries in respect of the High Seas and deep seabed.[112] The reaching of an agreement does not ensure that the agreement enter into force with any great speed. Sixty ratifications are required and one should recall that the UNCLOS itself, after a decade of negotiations, took a further twelve years to enter into force.[113] The BBNJ Agreement is the first general instrument to govern fair and equitable use of marine genetic resources in areas beyond national jurisdiction (including the Central Arctic Ocean). It also enhances the available processes on environmental impact assessment and MPAs. For the first time in a global law of the sea instrument, it requires States Parties to integrate traditional knowledge of Indigenous and local communities and uphold their rights.[114]

Mining on the deep seabed in the Arctic may not be an immediately attractive prospect so long as mining in temperate zones has yet to be tested but the International Seabed Authority (ISA) regulates any exploitation of the seafloor beyond the limits of the continental shelf under the Arctic Ocean (albeit a relatively small Area that is very difficult to access).[115] The ISA has to date taken a cautious approach to the Area under the Southern Ocean. This reflects uncertainties regarding potential conflict with provisions of the Madrid Protocol (that bans mining activities south of the 60°S parallel at least under the jurisdiction of its Parties) and the regime for the deep seabed under the 1994 Agreement.[116] The issue is further complicated by doubts about whether the Antarctic continent can generate a continental shelf, given the lack of recognition of State territorial claims in Antarctica and the freezing of the same under Article IV.[117] Until a few years ago, an ISA-published map of deep seabed under its jurisdiction excluded all the ocean below the 60°S parallel but it has since been removed from the public domain.[118] The more recent map on the ISA website is cut off at the foot of Patagonia.[119]

These three examples of the ongoing operation and relevance of global fora – the IMO, the BBNJ Agreement and the ISA – demonstrate that international law still very much governs human activities in the polar regions. The regimes may not be as robust as some would desire in terms of environmental security but international cooperation through these fora offers one of the best opportunities to strengthen protections.

Conclusion

The distinct bodies of law in the Arctic and Antarctic as well as global law and institutions with specific impacts on the polar regions have so far proven hardy enough to withstand the Russian attack on Ukraine. Geopolitical alliances may be shifting (though that is nothing new), trust between neighbours undermined, and cooperation increasingly challenging for some years to come. ‘Soft’ fora for cooperation are particularly vulnerable but the legal institutions remain operative. The above examples indicate not only that international law is resilient and continues to govern human and State activities at the Poles but in many contexts is little affected by the Russian conduct. Moreover, while in blatant violation of the ius ad bellum in Ukraine, the Russian Federation is ostensibly committed to international law in the polar regions even when the results do not fully align with its ambitions. This is demonstrated in its most recent submission to the CLCS in respect of the Gakkel Ridge.

A commitment to legal solutions to disagreements and disputes remains critical to the stability of the international order. The onus is on all parties, States and non-State actors alike, to insist on legal norms and processes to ensure that the near eighty-year peace in the polar regions endures. Experts in polar law are required to identify and pursue solutions to the many outstanding challenges.

[1] Note on spelling: there is no single preferred spelling of Saami/Sámi/Sami as it depends on the Saami language being used. In this article, the spelling ‘Saami’ will be preferred as per Saami Council, unless in reference to another proper noun, e.g., Sámi Parliament of Finland, Girjas Sami Village, etc.

[2] The author thanks Timo Koivurova, Nikolas Sellheim, Marc Lanteigne and Jonathan Wood as well as the two anonymous reviewers for their excellent comments on an earlier draft of this paper. She also thanks Timo Koivurova and Akiho Shibata for sharing background documents. All errors are the responsibility of the author.

[3] ‘Ukraine Refugee Situation’ (UN Operational Data Portal, last updated 26 June 2023) <https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine> accessed 29 June 2023; ‘Country Profile: Ukraine’ (Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, last updated 24 May 2023) <https://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/ukraine> accessed 29 June 2023.

[4] Timo Koivurova and others, Arctic Cooperation in a New Situation: Analysis on the Impacts of the Russian War of Aggression: Government Report 2022:3 (Government of Finland, 2022), 33.

[5] Charter of the United Nations 1 UNTS XVI, Article 2(4).

[6] See, Rachael Lorna Johnstone, ‘Ukraine: Why this war is different’ (Polar Connection, 10 March 2022) <https://polarconnection.org/ukraine-war-different-2/> accessed 23 June 2023.

[7] On Polar law as an academic discipline, see Rachael Lorna Johnstone, Yoshifumi Tanaka and Vibe Ulfbeck, ‘Polar Law as a Burgeoning Discipline’ in Yoshifumi Tanaka, Rachael Lorna Johnstone and Vibe Ulfbeck (eds), Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (Routledge 2023) 3-6.

[8] See, ibid, 5.

[9] Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts 2001 in Report of the International Law Commission on the Work of its Fifty-third Session, UN GAOR, UN Doc A/56/10 (2001) (ILC Articles on State Responsibility), article 29.

[10] See also, ibid, article 30.

[11] Ibid, articles 42 and 48-54.

[12] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969, 1155 UNTS 331 (VCLT) article 60.

[13] ILC Articles on State Responsibility (n 9) Articles 26 and 50.

[14] See, Johnstone (n 6) on Russia’s purported justifications and why they do not stand up to scrutiny.

[15] Yoshifumi Tanaka, Rachael Lorna Johnstone and Vibe Ulfbeck, ‘Polar Legal System’ in Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (n 7), 18-22.

[16] Ibid, 22-23.

[17] Ibid, 25-27.

[18] On the obligation of all States to uphold peremptory norms of international law, see ILC Articles on State Responsibility (n 9), Article 41(1).

[19] The Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation, Fairbanks, May 11, 2017. Entered into force, 23 May 2018, <http://hdl.handle.net/11374/1916>.

[20] ATCM, ‘Final Report of the Forty-fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting’ (23 May – 2 June 2022) Vol I (ATCM XLIV); ‘Helsinki Antarctic Meeting Culminates in Agreement on Climate Declaration,’ (Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, 14 June 2023) <https://um.fi/news/-/asset_publisher/GRSnUwaHDPv5/content/helsingin-etelamanner-kokous-huipentui-sopuun-ilmastojulistuksesta/35732> accessed 27 June 2023.

[21] https://web.archive.org/web/20220320105358/https://www.rsr-online.ru/news/2022-god/obrashchenie-rossiyskogo-soyuza-rektorov1/ translation by Jonathan Wood.

[22] Ekaterina Zmyvalova, ‘The Impact of the War in Ukraine on the Indigenous Small-numbered Peoples’ Rights in Russia’ (2022) 13 Arctic Review on Law and Politics, 407, 409-410.

[23] Mikhail Gorbachev, ‘Speech in Murmansk,’ (1 October 1987) <https://www.barentsinfo.fi/docs/Gorbachev_speech.pdf> accessed 26 June 2023.

[24] Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council, September 19, 1996 (Ottawa Declaration), <https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/85> accessed 26 June 2023.

[25] United States, Department of State of the United States of America, Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation Following Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine (3 March 2022) <https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-arcticcouncil-cooperation-following-russias-invasion-of-ukraine> accessed 26 June 2023.

[26] United States, Department of State of the United States of America, Joint Statement on Limited Resumption of Arctic Council Cooperation (8 June 20223) <https://www.state.gov/joint-statement-on-limited-resumptionof-arctic-council-cooperation> accessed 26 June 2023; Timo Koivurova, ‘Russia’s War in Ukraine: What are the Consequences to the Cooperation in the Arctic Council?’ (Finnish Institute in Japan: Science Tuesday, 28 February 2023) <https://sciencetuesday0228.peatix.com> accessed 28 February 2023.

[27] ‘Joint Statement of the Arctic States and Indigenous Permanent Participants issued on the occasion of the 13th Meeting of the Arctic Council on 11 May 2023’ (Arctic Council, 11 May 2023) <https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/3146> accessed 26 June 2023.

[28] Ibid.

[29] ‘Norwegian Chairship Hosts First Meeting with Working / Expert Group Chairs and Secretariats’ (Arctic Council, 15 June 2023) <https://arctic-council.org/news/norwegian-chairship-hosts-first-meeting-with-working-expert-group-chairs-and-secretariats/> accessed 29 June 2023.

[30] See, Malte Humpert, ‘Russia Amends Arctic Policy Prioritizing ‘National Interest’ and Removing Cooperation Within Arctic Council,’ High North News (Norway, 23 February 2023) <https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/russia-amends-arctic-policy-prioritizing-national-interest-and-removing-cooperation-within-arctic> accessed 23 June 2023.

[31] See, Mary Durfee and Rachael Lorna Johnstone, Arctic Governance in a Changing World (Rowman and Littlefield 2019) 67.

[32] Zmyvalova (n 22), 408.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Koivurova and others (n 4) 49.

[35] Saami Council, ‘Váhtjer Declaration 22nd Saami Conference’ (Saami Council, 11-14 August 2022), <https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5dfb35a66f00d54ab0729b75/t/6392e3f3069dea6ddeed9638/1670570996486/Va%CC%81htjer+declaration.pdf> accessed 29 June 2023.

[36] Koivurova and others (n 4) 50.

[37] Ibid, 8, 39- 42-44.

[38] ‘Comment by Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova on the Situation around the Northern Dimension and the Barents Euro-Arctic Council (BEAC)’ (The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, 11 March 2022) <https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/news/1803807/?lang=en> accessed 29 June 2023.

[39] Timo Koivurova and Akiho Shibata, ‘After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022: Can

we still cooperate with Russia in the Arctic?’ (2023) 59(e12) Polar Record 1, 3-4.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Koivurova and others (n 4).

[43] UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982, 1833 UNTS 397 (UNCLOS), Part XI, Section 4 and Annex II. See also, Durfee and Johnstone, 185-189 (for a simplified account of the process).

[44] The Area in this context is always, capitalized, see UNCLOS (n 43) article 1.

[45] Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, ‘ Recommendations of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in regard to the Partial Revised Submission made by the Russian Federation in respect of the Arctic Ocean on 3 August 2015 with Addenda Submitted on 31 March 2021’ (6 February 2023), para 73; Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, ‘Progress of work in the Commission on the Limits of the

Continental Shelf, fifty-seventh session’ (23 January–10 March 2023) UN Doc CLCS/57/2, Item 5.

[46] Russian Federation, ‘Partial Revised Submission of the Russian Federation in respect of the Continental Shelf of the Russian Federation in the South-East Eurasia Basin in the Arctic Ocean: Executive Summary’ (14 February 2023) <https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/rus02_rev23/23rusrev2e.pdf> accessed June 26, 2023.

[47] Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean (adopted 3 October 2018, entered into force 25 June 2021) OJ L 73, 15.3.2019, 3–8 (CAOFA).

[48] Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, ‘Report’ (23-25 November 2022) Doc CAOFA-2022-COP1-10. See also, paras 7 and Appendices 4 and 5.

[49] Ibid, Appendices 7 and 9.

[50] Ibid, para 3.

[51] CAOFA (n 47), Articles 4(4) and 5(1)(c).

[52] See, Inuit Circumpolar Council, ‘Inuit Delegates with Strong Presence at Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement Scientific Coordinating Group Meeting’ <https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/news/inuit-delegates-with-strong-presence-at-central-arctic-ocean-fisheries-agreement-scientific-coordinating-group-meeting/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[53] See Erik J Molenaar, ‘Participation in the Central Arctic Ocean Fisheries Agreement” in Akiho Shibata, Leilei Zou, Nikolas Sellheim, and Marzia Scopelliti (eds), Emerging Legal Orders in the Arctic: The Role of Non-Arctic Actors (Routledge 2019) (explaining the straddling stocks issue).

[54] See also, Koivurova and others (n 4) 36-37.

[55] Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic (adopted 12 May 2011, entered into force 19 January 2013) <https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/531> accessed 27 June 2023; Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (adopted 15 May 2013, entered into force 25 March 2016) <https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/529> accessed 27 June 2023; Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation (adopted 11 May 2017, entered into force 23 May 2018) <https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/handle/11374/1916> accessed 27 June 2023.

[56] Koivurova and Shibata (n 39) 5-6.

[57] Durfee and Johnstone (n 31) 222.

[58] See also Koivurova and others (n 4) 37.

[59] Zmyvalova (n 22) 410-11; Amy Mackinnon, ‘Russia is Sending its Ethnic Minorities to the Meat Grinder,’ Foreign Policy (Washington DC, 23 September 2022) <https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/09/23/russia-partial-military-mobilization-ethnic-minorities/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[60] Sanila-Aikio v Finland (2018) UN Human Rights Committee, UN Doc CCPR/C/124/D/2668/2015.

[61] ‘Controversial Sámi Bill Runs Aground in Parliamentary Committee’ Yle News (Helsinki, 24 February 2023) <https://yle.fi/a/74-20019662> accessed 27 June 2023.

[62] HR-2021-1975-S, (case no. 20-143891SIV-HRET), (case no. 20-143892SIV-HRET) and

(case no. 20-143893SIV-HRET), Supreme Court of Norway, Judgment, 11 October 2021.

[63] See, ‘— Days of Human Rights Violations. Illegal Income Since the Supreme Court Verdict’, <https://fosenticker.github.io/Fosen/?fbclid=IwAR1YAP_wDMLYDMKNiadX-fH5TvAbQ0ok-Fx58d7QKOTgS8Uh0atNvu4hHeo> accessed 28 June 2023 (for a ticker counting the days since the verdict and estimating the profits of the energy firm).

[64] Office of the chancellor of justice v Girjas sameby, case no T 853-18, Supreme Court of Sweden, 23 January 2020.

[65] Haaland v Brackeen, Docket nos 21-376, 21-377, 21-378 and 21-380, Supreme Court of the United States, 15 June 2023.

[66] Edwin A Miles, ‘After John Marshall’s Decision: Worcester v. Georgia and the Nullification Crisis’ (1973) 39(4) The Journal of Southern History 519–544, 519.

[67] The Constitutional Commission of Greenland, ’Forfatningskommissionens Betænkning’ (The Constitutional Commission 2023).

[69] Grønlands Forsoningskommission, ’Vi forstår fortiden; Vi tager ansvar for nutiden; Vi arbejder sammen for en bedre fremtid’ (Office of the Prime Minister of Greenland 2017).

[70] Christine Hyldal, ‘Hele Inatsisartut er enig: Der skal laves en udredning om spiralkampagnen’ KNR (Nuuk, 25 May 2022) <https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/hele-inatsisartut-er-enig-der-skal-laves-en-udredning-om-spiralkampagnen> accessed 27 June 2023; see also, DR, ’Spiralkampagnen’ (podcast) (Copenhagen 6 May 2022) <https://www.dr.dk/lyd/p1/spiralkampagnen> accessed 28 June 2023 (which first unveiled the scale of the Danish measures); Helle Nørrelund Sørensen, ‘Politikerne er enige: Afkolonisering af Grønland skal undersøges’ KNR (Nuuk, 4 June 2022) <https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/politikerne-er-enige-afkolonisering-af-gr%C3%B8nland-skal-unders%C3%B8ges> accessed 27 June 2023; [70] Office of the Prime Minister of Denmark, ‘Danmark og Grønland beslutter historisk udredning af de to landes forhold’ (9 June 2022) < https://www.stm.dk/presse/pressemeddelelser/danmark-og-groenland-beslutter-historisk-udredning-af-de-to-landes-forhold/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[71] Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen, ‘Sannhet og forsoning – grunnlag for et oppgjør med fornorskingspolitikk og urett. Rapport til Stortinget fra Sannhets- og forsoningskommisjonen’ (1 June 2023).

[72] Sanningskommissionen för det samiska folket, ‘Om kommissionen’ <https://sanningskommissionensamer.se/om-kommisionen/> accessed 24 May 2023; Kväner Lantalaiset Tornedalinger, ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Tornedalians, Kvens and Lantalaiset’ <https://komisuuni.se/en/start-en/> accessed 24 May 2023.

[73] ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission Concerning the Sámi People’ (Finland) <https://sdtsk.fi/en/home/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[74] United States Senator Lisa Murkowski, ‘Murkowski Joins 26 Senators to Reintroduce Bill Seeking Healing for Stolen Native Children and their Communities’ <https://www.murkowski.senate.gov/press/release/murkowski-joins-26-senators-to-reintroduce-bill-seeking-healing-for-stolen-native-children-and-their-communities> accessed 27 June 2023.

[75] See, Priyasha Saksena, ‘Jousting over Jurisdiction: Sovereignty and International Law in Late Nineteenth Century South Asia’ (2019) 38(2) Law and History Rev 419 (on divisible sovereignty in colonial South Asia of the 19th century).

[76] The Antarctic Treaty (adopted 1 December 1959, entered into force 23 June 1961) 402 UNTS 71, Article IV; see also Patrizia Vigni, ‘Territorial Claims to Antartica’ in Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (n 7), 33-46.

[77] EU Parliament, Resolution of 9th October 2008 on Arctic Governance (11 December 2008) OJ C 316 E 41, December 11, 2008; see also Greenpeace, ‘Protecting Lands: Creating an Arctic Sanctuary’ <https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/arctic/arctic-sanctuary/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[78] Foreign Ministers of Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the US, ‘The Ilulissat Declaration’ (28 May 2008); Inuit Circumpolar Council, ‘A Circumpolar Inuit Declaration of Sovereignty in the Arctic’ (28 April 2009), <https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/icc-international/circumpolar-inuit-declaration-on-arctic-sovereignty/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[79] Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals (adopted 1 June 1972, entered into force 11 March 1978 1080 UNTS 175 (CCAS); Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (adopted 20 May 1980, entered into force 7 April 1982) 1329 UNTS 47 (CAMLR Convention).

[80] Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (adopted 4 October 1991, entered into force 14 January 1998) 2941 UNTS 1.

[81] On consensus decision-making, see Kees Bastmeijer, ‘Introduction: Madrid Protocol 1998 – 2018. The need to address ‘the Success Syndrome’ (2018) 8(2) The Polar Journal 230.

[82] ‘ATCM XLIV – CEP XXIV List of Participants,’ ATCM XLIV (n 20) Doc AD003. One of the ‘virtual audience’ for the main ATCM attended the CEP as the Russian representative. The Head of delegation and alternative both attended the CEP virtually as did the other three who had also joined the ATCM as virtual audience. The ATCM alternate for the Russian Federation did not attend the CEP.

[83] Ibid. Belarus had 4 ATCM delates, one of which was also a CEP delegate, plus one other CEP delegate. Ukraine had 7 ATCM delegates, of which two were also CEP delegates.

[84] ‘25 Antarctic countries supported Ukraine and staged a démarche to the representative of the Russian Federation during the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting’ (Ukraine State Institution National Antarctic Scientific Center, 24 May 2022) <http://uac.gov.ua/en/25-antarctic-countries-supported-ukraine-and-staged-a-demarche-to-the-representative-of-the-russian-federation-during-the-antarctic-treaty-consultative-meeting/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[85] ATCM XLIV (n 20).

[86] By definition and design, only well-resourced States can become new Consultative Parties as they must demonstrate scientific work in Antarctica to qualify for consultative status, see Antarctic Treaty, article IX.

[87] Helsinki Declaration on Climate Change and the Antarctic, Resolution E (2023) of the Forty-fifth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting’ available from Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland (9 June 2023) <https://um.fi/current-affairs/-/asset_publisher/gc654PySnjTX/content/helsinki-declaration-on-climate-change-and-the-antarctic> accessed 27 June 2023.

[88] The ATCM would not be the appropriate forum in which to negotiate climate mitigation, adaption or financing obligations; rather that takes place – or does not take place as the case may be – at the globally representative UN Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties: ‘Conference of the Parties’ (United Nations Climate Change) < https://unfccc.int/process/bodies/supreme-bodies/conference-of-the-parties-cop> accessed 27 June 2023.

[89] Timo Soini, ‘Statement by the Chair on the Occasion of the Eleventh Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council’ (Rovaniemi, 6-7 May 2019) < https://um.fi/documents/35732/0/Rovaniemi-Statement-from-the-chair_FINAL_840AM-7MAY.pdf/8ae0c2a6-fe6a-43e2-2326-f145e8a536cf?t=1557218507134> accessed 27 June 2023; see also Timo Koivurova, ‘Lessons from Finland’s Chairmanship of the Arctic Council’ (2020) 12 Yearbook of Polar Law 197.

[90] See Alan D Hemmings and Timo Koivurova, ‘International Regulation of Mineral Resources Activities in the Polar Regions’ in Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (n 7) 310-13.

[91] Question of Antarctica, UNGA Res 47/57 (9 December 1992), para 9.

[92] See, Hemmings and Koivurova, 311-12.

[93] See, ‘Helsinki Antarctic Meeting Culminates in Agreement on Climate Declaration’ Statement by the Host Country (Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland, 14 June 2023) <https://um.fi/current-affairs/article/-/asset_publisher/iYk2EknIlmNL/content/helsingin-etelamanner-kokous-huipentui-sopuun-ilmastojulistuksesta/35732?fbclid=IwAR2avMNIkXIm0dYS1ek6qclunf1a8xLPuDrdSj7cTTAv8SGDcw47_81sOxs> accessed 27 June 2023.

[94] See Kees Bastmeijer and others, ‘Regulating Antarctic Tourism: the Challenge of Consensus-Based Decision-Making’ (2023) AJIL doi: 10.1017/ajil.2023.34 (on the challenges of regulating tourism under consensus system).

[95] Ibid, 2-3.

[96] Antarctic Treaty (n 76), Article IX(2).

[97] Andrew Silver, ‘Ukraine Freezes Belarus Out of Antarctic Research Work’ (Research Professional News, 16 June 2023) <Ukraine freezes Belarus out of Antarctic research work – Research Professional News> accessed 29 June 2023.

[98] See Akiho Shibata, ‘Looking Towards 2026 ATCM (in Kobe?): Some Homework to Do’ (Kobe PCRC Antarctic Open Symposium Series 2022, 2 December 2022) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZjCjojfqdqM> accessed 27 June 2023.

[99] See Rachael Lorna Johnstone, ‘Global Polar Law?’ in Kamrul Hossain (ed) Current Developments in Arctic Law X, 70, 72.

[100] CAMLR Commission, ‘Third Special meeting of the Commission’ (19-23 June 2023), <https://meetings.ccamlr.org/en/ccamlr-sm-iii> accessed 29 June 2023.

[101] See, e.g., ‘International Meeting on Antarctic Ocean Protection Ends with No Further Progress’ (Nature MCM/Martin CID Magazine, 25 June 2023) < https://martincid.com/en/2023/06/international-meeting-on-antarctic-ocean-protection-ends-with-no-further-progress/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[102] See Kees Bastmeijer and Rachael Lorna Johnstone, ‘Environmental Protection in the Antarctic and the Arctic: the Role of International Law’ in Malgosia Fitzmaurice and others (eds) Research Handbook of International Environmental Law (Edward Elgar 2021) 459, 470 (on science-based decision-making as a barrier to substantive action on Antarctic MPAs).

[103] See, Gastautor, ‘China and Russia are Blocking Creation of a Third Antarctic Marine Protected Area’ Polar Journal (Zurich, 19 June 2023) <https://polarjournal.ch/en/2023/06/19/china-and-russia-are-blocking-creation-of-a-third-antarctic-marine-protected-area/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[104] Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment (1972) 11 ILM 1416.

[105] Madrid Protocol (n 80), Annex I; CCAMLR Secretariat, ‘Elimination of IUU Fishing and the World’s First Catch Document Scheme’ (CCAMLR, 7 October 2021) <https://40years.ccamlr.org/elimination-of-iuu-fishing-and-the-worlds-first-catch-document-scheme/> accessed 27 June 2023.

[106] Maria Katsivela, ‘The IMO and Outstanding Maritime Safety and Environmental Issues under the Polar Code’ in Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (n 7), 325, 332-341.

[107] ATCM XLIV (n 20), para 345.

[108] ‘Non-Governmental international Organizations which have been granted consultative status with IMO’ (International Maritime Organization) <https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/ERO/Pages/NGOsInConsultativeStatus.aspx> accessed 27 June 2023.

[109] ASOC report to the ATCM, Agenda item ATCM 4 (22 April 2022) <https://www.asoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/ASOC-report-to-ATCM.pdf> accessed 27 June 2023.

[110] Paris Agreement (adopted 12 December 2015, entered into force 4 November 2016) 3156 UNTS

[111] Fiona Harvey, ‘Shipping Emissions could be Halved without Damaging Trade, Research Finds,’ The Guardian (London, 26 June 2023) <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jun/26/shipping-emissions-could-be-halved-without-damaging-trade-research-finds> accessed 27 June 2023.

[112] Draft Agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction,’ UN Doc A/CONF.232/2023/L.3 (BBNJ Agreement).

[113] Ibid, Article 68.

[114] Ibid, Articles 7, 13, 19, 21, 24, 26, 31, 32, 35, 37, 41, 44, 48, 49, 51 & 52. See also Preamble.

[115] Edwin Egede, ‘The International Seabed Authority and the Polar Regions’ in Routledge Handbook of Polar Law (n 7) 342, 347-351.

[116] Ibid, 354-355.

[117] Ibid, 353-4.

[118] The map is reproduced in Donald R Rothwell and Tim Stephens, The International Law of the Sea (2nd ed. Bloomsbury 2016) 129.

[119] MarineRegions.org, GEBCO, NOAA, ‘Map of the Area’ (International Seabed Authority) <https://www.isa.org.jm/maps/map-of-the-area/> accessed 27 June 2023.