It is fair for one to ask, what does that quotation have to do with International Relations (IR) theory? For me, the quotation represents a push factor that has placed me into a metaphorical crossroads. By looking at this crossroads through an IR lens, I find myself in many long-standing and contemporary IR debates: realism versus institutionalism, rationalism versus social constructivism, and the levels of analyses in which to apply these modes of thought. I will look at myself at three levels. The first layer will be the State in which I current reside (Iceland), which being a “small state,”[1] tends to be more institutionalist than the greater powers. Next, I will look at my role in academia both as a student and a research fellow working at the Stefánsson Arctic Institute, which is one institution in the “mosaic of cooperative arrangements emerging in the Arctic.”[2] Finally, and perhaps most importantly, I will analyze myself as an American abroad. Using the concept of “ontological security”[3] and Foucault’s definition of the individual, I will show that I am what I will coin “Schrödinger’s American.” My father may call himself one as well, yet living abroad (and questioning if I’ll return), I believe personally amplifies the moniker. Section II will briefly define Schrödinger’s American and expound upon the words of my father to give context on how I define myself as an individual in this contribution. Section III will provide the definition of the layers of analysis chosen in order to dissect Schrödinger’s American, which will be divided into three subsections with each subsection analyzing the school of IR thought applicable to that layer within the Arctic.

Schrödinger’s American: A Definition of the Self

Schrödinger’s American is what I define as the state of being American, in the realist sense of acting for individual benefit as an American subject, while at the same time actively participating in institutional arrangements in other sovereign States yet still begrudgingly being a part of the American cultural hegemon. My father’s words have stuck with me since our last email exchange; exchanges that have gone on for pages and years, ranging from topics as inane as college football to as serious as my career choices and his personal health. Yet despite the distance or time apart, there has always been a sense of levity, a knowing undertone of humor or even self-deprecation, when it comes to politics and the current affairs in the United States. COVID-19, and the United States’ response to it, has changed his tone. As a nephrologist who works at three different clinics and prisons in southwest Georgia, he puts himself at risk every day given his age (68) and health (diabetic). In a state that President Donald Trump criticized for opening too early,[4] my father has become disillusioned. He believes he is seeing the worst that the media, in its quest for viewership, and the populace of my town, by equating the inconvenience of social distancing measures with the current and historical oppression suffered by racial minorities, has to offer. I share his view and concern; I no longer feel the call of home as I once did.

My time in Iceland is too ephemeral to be called an expat, and my feeling towards home not callous enough to call myself a political exile. I exist somewhere in the interstitial fluid of being an American who cannot go home due to COVID-related and educational reasons yet may have to go home for personal and financial ones in the near future as I am an only child, regardless of whether I want to or not. Then I remember my father’s words actively telling me to stay away, and the loop of emotions (wanting to go home to make a difference and the guilt of not being there back to the happiness of being able to extract myself from all the vitriol and enjoy my sanctuary) begins all over again. I am at once American and not American; a player for which no IR theory can predict his actions. Despite that gap in IR theory for the individual, I will attempt to do so in the following sections by breaking myself down layer by layer.

The Layers of Analysis

The levels of analysis question has been a constant debate throughout the development of IR thought and theory. David Singer “examine[d] the theoretical implications and consequences of two of the more widely employed levels of analysis: the international system and the national sub-systems.”[5] His focus on the two levels has been further critiqued by scholars as new modes of thought were explored. From Waltz, “who stands squarely in the Realist tradition,”[6] gives us “three distinct categories or layers of analysis: this individual, the state, and the international system.”[7] There are scholars who argue for even more layers of analysis. For example, Barry Zellen argues for the creation of a new taxonomy:

In today’s world, we have persistent, organic state-level entities (POSLEs) as well as ephemeral, and synthetic state-level entities (ESSLEs), some which are nation-states but others which are multi-ethnic states, the former widely perceived to be more enduring over time than the latter. We also have tribes, sects, and clans, some that reside within states, some between and across state boundaries (thereby creating fault lines for future inter- and intra-state conflicts), and those which have survived into the contemporary era are the POSSEs, so-named for their endurance. And now, with the proliferation ofnetworks and digital communications systems, we have neo-tribal entities which could, in time, evolveinto persistent and organic units of world politics, much like more traditional clans, sects and tribes. Indeed, organized crime networks and other illicit trade networks show many parallels with POSSEs, and could in time join their ranks.[8]

This new taxonomy redefines the traditional layers of analysis as used by Singer and Waltz in order to encompass layers not considered by them, such as tribes that are interwoven into the fabric of the United States and Canada and with whom they have a complicated history and various current levels of co-management schemes.

My choice of three layers is a hybrid of both the Waltzian and Zellen perspective. I choose to redefine the concept of the individual from Waltz, yet add it into the taxonomy of Zellen. Waltz’ definition of the individual is problematic given that his three layers are viewed through the “notion [as] the causes of war”[9] rather than curators of a Kantian peace.[10] I place this altered definition, one who is attempting to curate the Kantian peace, of the individual into “the Ethereal dimension [of Zellen] . . . [as] [i]t is one that exists in the mind and heart, such as the world’s religions.”[11] While my perspective on the self is not religious in nature, it is more attached to the Foucault vision of the self and can be considered as to what exists currently in my heart and mind. Furthermore, the addition of my current role in academia shifts towards the mode of thought of Oran Young as an institutionalist rather than that of the realist Waltz when looking at the international system layer.

Layer One: The State of Iceland

Iceland plays a unique role within the theory of international relations. It has found itself in a geographically advantageous region, an Arctic state between Europe and North America, yet does not have aspects of normal Westphalian state, such as a standing army. As “[a] small state with limited resources, [Iceland] cannot afford to just observe such first-order threats . . . Like any modern polity, it needs to be aware of all the different aspects of security – military, political, economic or functional – that are crucial for its survival. Since it can rarely find the answers on its own, and its limited internal market also makes its prosperity highly dependent on outside relations, it needs a conscious national strategy to find the external support (or ‘shelter’) and the openings required at the most reasonable price.”[12] Iceland acts both in an institutional capacity in some regards but cannot be denied that it has acted under the realist school of thought when it comes to certain issues, such as fisheries and maritime boundaries.[13]

For hard security issues, Iceland has been reliant on the United States and NATO strategic cover,[14] making it more reliant on institutions, yet with the current Icelandic government not wishing to have the United States back on its sovereign soil,[15] Iceland has rejected being a NATO “vassal” and sees itself as a thought leader for bridging East-West dialogue, especially with its Chairmanship of the Arctic Council from 2019-2021 with it’s motto “Together towards a sustainable Arctic.”[16] By being Euro-sceptic, yet still being in the EEA and Schengen Zone, Iceland has walked the tight rope of being a Western ally, yet not committing fully enough to bother other regional and world powers such as the Russian Federation and China. The former is an important trade partner while the latter has been a large investor in new shipping infrastructure projects. For example, Iceland “advocates cooperation with BRICs and other Asian powers for diversifying Iceland’s trade relations, investment sources and economic base. Iceland has not only supported several nations’ wishes to become AC observers, but was one of the first OECD states to conclude a Free Trade Agreement with China, and recently gave one seabed exploration licence to a part Chinese consortium.”[17]

In further support of its institutionalist approach, “Iceland also participates with Norway, Russia and all EU members in the EU’s ‘Northern Dimension’ program, which offers funding for joint development projects and addresses the High North through the ‘Arctic window’ scheme.[18] As a founder-member of the Barents Euro-Arctic Council, Iceland supports that organization’s efforts to stabilize relations and promote development across the land borders of Russia, Norway, Sweden and Finland. Significantly more active, however, is Iceland’s diplomacy within the Nordic Cooperation framework, comprising the Parliamentary Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM), and its West Nordic sub-group.”[19]

Iceland is not only a pivot point for realism versus institutionalism, the creation of small state studies has led to a new discourse of which Iceland is a prominent member:

The changes in IR theory that came with the end of the ‘bipolar freeze’ (and, in some cases, the rise of nationalism) – in particular social constructivism with its focus on international norms, identity and ideas – may have eased the opening of the field of small state studies again in the 1990s. If not only relative power and/or international institutions matter, but also ideational factors, small states may gain new rooms of maneuver in their foreign policy. They may, for instance, be able to play the role of norm entrepreneurs influencing world politics they may not only engage in bargaining with the other (greater) powers, but also argue with them, pursue framing and discursive politics, and socially construct new, more favorable identities in their relationships.[20]

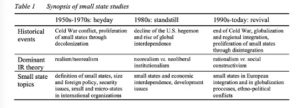

A summary of Iceland’s IR debates as a small state is covered in Table 1 below:[21]

My opinion is that Iceland falls under the social constructivist view even though it is more of a meta-theory than a theory in and of itself. Social constructivists “view cooperation as a result of social interaction and collective identity formation, not inter-state or intergovernmental bargaining. They do not accept the idea that the interests of states are fixed and independent of social structures. It is this basic assumption that makes room for the introduction of other mechanisms for understanding international cooperation.”[22] This can be seen in the changing concept of Iceland to the European Union; in 2013, the government in power wanted to join yet the current administration is Euro-sceptic.[23] Rather than the bargaining of governments, Iceland chooses not to enter into intergovernmental bargaining and has begun taking actions based on social structures. An example of acting through identity is its move to “Nordicness.” At present, “Iceland’s foreign policy is, to a greater extent, constructed by the Nordic environment, with its shared culture and institutions, than during the Cold War. Nordicness has never been more important to Iceland’s foreign policy in terms of increased security and defence cooperation between the Nordic states.”[24] This is due to “the end of the Cold War, the departure of the US military from Iceland, and the US government’s refusal to provide Iceland with a rescue package during the 2008 economic crash have transformed the impact of the Nordic environment on Iceland’s foreign policy. Accordingly, the culturally dense Nordic environment is having more impact on Iceland’s foreign policy and Iceland is moving higher on the continuum the degree of construction of the units by the environment in the security cultures model.”[25] By progressing towards a collective identity of Nordicness, we see Iceland slowly moving away from rationalist thought and the European Union towards other Scandinavian countries that balance foreign relations between both East and West, such as Norway and Finland.

Layer Two: My Role in Academia

The layers of analysis are not mutually exclusive of one another but rather may contradict or complement one another in an attempt to be complicit with or rebel against the actions of a larger entity. We see the complementary aspect of my work at the Stefánsson Arctic Institute and my role at the University of Akureyri contribute to the institutionalist route that Iceland seems to prefer. For example, my office borders the offices of the Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna, one of the six working groups of the Arctic Council, the premier multilateral forum for Arctic discourse, and one in which Iceland views itself as a current thought leader given its possession of the Chairmanship.

Education has been a key institution through which Iceland has enhanced its Arctic viewpoint. “When identifying key actors within Iceland’s Arctic initiatives one cannot exclude academia. Iceland has had a strong presence in the EU’s and other international organisations’ scientific and educational networks. Akureyri University . . . runs an International Polar Law LLM and MA programmes, and regularly hosts international Arctic conferences.”[26] Part of my work at the Stefánsson Arctic Institute will be in its JustNorth program, which is based off an IR perspective of Mark Nuttall. Part of the program states “there has been a marked policy move towards promoting mining as a major industry, including with the Greenlandic parliament voting to repeal Greenland’s zero-tolerance policy on uranium mining. While resource development in Greenland represents a potential key source of income, the process of resource exploitation also raises the question of how to ensure that gains from resource development accrue to the people of Greenland.”[27] This research was inspired by Mark Nuttall and his own exploration of a realist versus institutionalist Greenland given the rising mining sector.[28] Thus through an Icelandic institution, I’ll be furthering the independence dialogue of a West Nordic sub-national entity of the Kingdom of Denmark. I’ll be continuing this Icelandic institution pursuit by teaching in the University of Iceland’s Arctic Studies’ Graduate Diploma program as a PhD Candidate in Political Science.

This institutionalist approach to realize goals that are generally thought of in the school of realism stands in for the complexities of Arctic governance “where social institutions rest on ideas, even when they have been around so long that it is difficult to ascertain the origins of the relevant ideas and trace the pathways through which they became influential. To my way of thinking, a research program that can profit from the insights of alternative schools of thought rather than becoming enmeshed in the sectarian battles among them has much to recommend it.”[29] The Stefánsson Institute is that type of body. Detached from sectarian, ideological disputes, it goes about its work unintentionally reinforcing Iceland’s institutionalist framework but with realist end goals of a possible independent Greenland, yet at the same time contributing to certain constructivist arguments by exploring what individuals want within Greenland and thus identifying social norms.

Layer Three: The Individual

This layer has been somewhat defined in Section II of the contribution, yet needs meat added to the bone so to speak. As stated above I place myself in the ethereal dimension as laid out in Zellen where we look at what is in the heart and mind of subjects, yet those ideas seem to be conflicting with my current identity as American citizen. Zellen does not explicitly analyze the individual as Waltz does, yet placing the concept of the individual or subject into Zellen’s taxonomy makes logical sense. For Foucault, “subject is an entity which is capable of choosing how to act within the constraints of the given historical and cultural context. Foucault makes the distinction between the subject and the individual. The individual is transformed into the subject and the transformations take place as a result of outside events and actions undertaken by the individual; different forms of power relations makes individuals subjects. Foucault himself proposes in his essay The Subject and Power (1982) two meanings of the word ‘subject:’ subject to someone else by control and dependence; and tied to his own identity by a conscience or self-knowledge. Both meanings suggest a form of power which subjugates and makes subject to.”[30]

Through my actions as an individual, I have been transformed into the two various definitions of the subject as defined by Foucault. First, I am a subject of Iceland based on my dependence of financial support and residence here and control by being subject to their laws, yet I am an American subject based on my own self-knowledge. These two seem reconcilable until we look at the “form of power.” The form of power for me being an Icelandic subject is the willingness to follow the laws and choosing to be here despite COVID-related issues; however, my being an American subject stems from the cultural hegemony of America and the lasting impact it has created. In a sense this goes back to the German realist Morgenthau in which there is a “constant struggle for power”[31] and “that there was no harmony of interest among nations, that national objectives would be governed, as they always had been, by the dictates of self-interest.”[32] America continues to have a form of power, one of culture, rather than what Morgenthau sees as hard power, over its subject. This cultural hegemony is hard to overcome and has become a label, or even a stigma, in many arenas. Iceland does not have this same cultural power; thus, my two concepts subject under Foucault, one willing and unwilling, are imbalanced powers with the unwilling power dynamic being stronger. This instills what I call the Schrödinger’s American; in one sense I am and will always be American even if I actively involve myself in institutions that may not work for the benefit of America.

Is there a solution for this dilemma? I take comfort in the fact that my father finds that American exceptionalism is dead, yet that has become a matter of politics, which is outside the scope of this paper. I do also take comfort that I may be caught up in Iceland’s nascent search for “ontological security.” Under this rubric “states also engage in ontological security-seeking. Like the state’s need for physical security, the need for ontological security is extrapolated from the individual level. Ontological security refers to the need to experience oneself as a whole, continuous person in time — as being rather than constantly changing — in order to realize a sense of agency.”[33] While I only may be one individual, I found Iceland in a time of national ascent both from an extant, international point of view as the Arctic has become ascendant in geopolitics by other countries and at the latent, national level, given that Iceland is actively promoting its role within that space through domestic strategies and the Chairmanship of the Arctic Council. “Importantly, for theorists of ontological security individual identity is formed and sustained through relationships. Actors therefore achieve ontological security especially by routinizing their relations with significant others. Then, since continued agency requires the cognitive certainty these routines provide, actors get attached to these social relationships.”[34] My time in Iceland has not been long enough and have not developed the certainty of routines, although I do have them. By continuing these routines, I will achieve deeper social relationships and thus provide ontological security not only to myself in the form of human security/development but provide it to the State as well. In conclusion, it is hopefully only a matter of time before the crisis resolves itself.

Conclusion

In this piece I have analyzed myself within on three different layers: the state, my work that contributes to the international system as well as the state, and the individual. At the state level, I find Iceland to be institutionalist rather than in the school of realism. Furthermore, Iceland, as a small state, has taken up the ideas of social constructivism by embracing its cultural identity of Nordicness in recent years after the United States withdrew from the base in Keflavik and did not provide financial support in 2008 during the financial crisis. In the second layer, I find myself contributing to institutionalist regimes, or as what Oran Young would call Regime Theory, yet going through these institutions may contribute to goals that some would define as realist; however, it is true that these schools are not mutually exclusive and may be used to complement one another. Finally, at the individual level, I find myself at an existential crossroads; torn between the power dynamics of an American hegemon and a small state with more limited capabilities which has made me subjects of two different state polities.

While this crisis is defined philosophically via Foucault, my crisis can be seen through the lens of international relations given that I am attempting to place myself within the ontological security paradigm of a state that is relatively new to the international scene. It is the powerful hegemon of the United States that continues to control my conscience and self-knowledge, yet my routines and social relationships will continue to develop in Iceland. As those social connections become more secure, my own ontological and human security will follow (both to myself and to the State), and I may be able to resolve my inner turmoil. I am a student of the Arctic, and I wish to continue to live in the Arctic. In doing so, I will have to overcome biases of culture that have been imprinted. It is a tough path to follow, but one I am excited to walk along.

References

[2] See generally Knudsen, Olav Fagelund, “Small States, Latent and Extant: Towards a General Perspective,” Semantic Scholar, (2002), available at https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/%3E-Small-States-%2C-Latent-and-Extant-%3A-Towards-a-Knudsen/a2852b2275ecb4b4bf9bcd2befb29f47f390f9b3 (Last accessed May 22, 2020).

[2] Young, Oran, “Governing the Arctic: From Cold War Theater to Mosaic of Cooperation,” Global Governance, Vol. 11, at pg. 9 (2005).

[3] See generally, Steele, Brent J., Ontological Security in International Relations: Self-identity and the IR State, (Routledge: New York and London) (2005).

[4] See Zeleny, Jeff, “Trump’s Angry Words to Georgia Governor Reverberate in State Capitals as Governors Move to Reopen States,” CNN Politics, (Apr. 27, 2020), available at https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/27/politics/trump-kemp-georgia-governors-reopen/index.html (Last accessed May 22, 2020).

[5] Singer, David J., “The Level-of-Analysis Problem in International Relations,” World Politics, Vol. 14, No. 1, at pg. 78 (Oct. 1961).

[6] Mearshimer, John J., “A Tribute to Kenneth Waltz,” Zu Diesem Buch, at pg. 11 (no date given).

[7] Id.

[8] Zellen, Barry, “Tribe, State, and War Balancing the Subcomponents of World Order,” Culture and Conflict Review, Vol. 3, No. 3, at pg. 2 (Fall 2009).

[9] Mearshimer, John J., note 7 supra, at id.

[10] See generally, Oneal, John R., & Russett, Bruce, “The Kantian Peace: The Pacific Benefits of Democracy, Interdependence, and International Organizations, 1885-1992,” World Politics, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 1-37, (Oct. 1999), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/world-politics/article/kantian-peace-the-pacific-benefits-of-democracy-interdependence-and-international-organizations-18851992/0BBD01FABBCAC18888792829960BEDD6 (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[11] Zellen, note 9 supra, at id.

[12] Bailes, Alyson, et al., “Iceland: Small but Central,” in Perceptions and Strategies of Arcticness in sub-Arctic Europe, at pg. 77, (Eds. Andris Sprüds and Toms Rostoks) (Latvian Institute of International Affairs: Latvia), (Jan. 2013), available at https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=e861e1f4-bc1f-0c38-efdd-be81f6aeda16&groupId=252038 (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[13] See generally, Fisheries Jurisdiction (United Kingdom v. Iceland), Merits, Judgment, I.C.J. Reports 1974, p. 3., available at https://www.icj-cij.org/files/case-related/55/055-19740725-JUD-01-00-EN.pdf (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[14] See id. at pg. 78.

[15] See Óskarsson, Ómar, “Left-Greens Reject NATO Project in Helguvík Harbor,” Iceland Monitor, (May 14, 2020), available at https://icelandmonitor.mbl.is/news/politics_and_society/2020/05/14/left_greens_reject_nato_project_in_helguvik_harbor/ (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[16] The Arctic Council, “Icelandic Chairmanship,” The Arctic Council, available at https://arctic-council.org/en/about/chairmanship/ (Last accessed May 24, 2020) (emphasis added).

[17] Bailes, note 13 supra, at pg. 85.

[18] The term “Arctic window” is a term of art used within the EU Horizon scheme, and its definition and practicality are outside the scope of this paper.

[19] Id. at pg. 84.

[20] Neumann, Iver B., & Gstöhl, Sieglinde, “Lilliputians in Gulliver’s World? Small States in International Relations,” Centre for Small State Studies, (Working Paper 1-2004), at pg. 12, (May 2004), available at http://ams.hi.is/wp-content/uploads/old/Lilliputians%20Endanlegt%202004.pdf (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[21] See id. at pg. 13.

[22] Rieker, Pernille, “EU Security Policy: Contrasting Rationalism and Social Constructivism,” Norwegian Institute of International Affairs, at pg. 6 (2004), available at https://nupi.brage.unit.no/nupi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2394641/WP_nr659_04_Rieker.pdf?sequence=3 (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[23] See Bailes, note 13 supra, at pp. 80-81.

[24] Thorhallsson, Baldur, “Nordicness as a Shelter: The Case of Iceland,” Global Affairs, at pg. 11 (Sept. 24, 2018), available at https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2018.1522507 (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[25] Id.

[26] Bailes, note 13 supra, at pg. 86.

[27] Personal communication with Joan Nymand Larsen, “Description of JustNorth Project,” electronic mail (Jan. 31, 2020) (on file with author) (citing Nuttall note 29 infra).

[28] See Nuttall, Mark, “Zero-Tolerance, Uranium and Greenland’s Mining Future,” Polar Journal, Vol. 3, pp. 368-83 (2013).

[29] Young, Oran, “Regime Theory Thirty Years On: Taking Stock, Moving Forward, International Organization, at pg. 4 (Sept. 18, 2012).

[30] Campbell-Thomson, Olga, “Foucault, Technologies of the Self and National Identity,” Working Paper presented at the British Educational research Association Annual Conference, at pg. 3, (London, United Kingdom) (Sept. 6-8 2011), available at http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/204173.pdf (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[31] Rosecrance, Richard, “The One World of Hans Morgenthau,” Social Research, Vol. 48, No. 4, at pg. 750 (Winter 1981).

[32] Id. at pg. 751.

[33] Mitzen, Jennifer, “Ontological Security in World Politics: State Identity and the Security Dilemma,” European Journal of International Relations, Vol. 12, No. 3, at pg. 342 (2006), available at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1354066106067346 (Last accessed May 24, 2020).

[34] Id.