The reflexivity of ethnography allows the curious stranger to connect personal experiences to the research question at play intimately. The curious stranger exposes the reader to observations that otherwise would not have come to light and provides first-hand accounts of the studied phenomena. Getting deeper data through reflexivity developed by the curious stranger can allow for more understanding of the topic to come to light. The curious stranger approach explores subject matter that would have remained in an unfamiliar setting using a more traditional research approach – a discussion often addressed within Arctic research. When discussing relevant Arctic research methodologies and ethics, the emphasis is on including indigenous knowledge (Arnfjord & Hovgaard, 2021; Denzin & Lincoln, 2014). The discussion often includes political positions and the discussion about how the research becomes relevant for the particular setting. The ethical discussion, and the relevance of research, are always present in our approach when entering the context – here formulated as being a curious stranger in an unfamiliar setting.

“For, to be a stranger is naturally a very positive relation; it is a specific form of interaction” (Simmel, 2006, p. 1).

Simmel’s (2006) stranger is a helpful analogy to illustrate the ‘outsider’ researcher entering an unfamiliar setting to gather field research and the relationship-building dynamics between outsiders and locals. Simmel’s stranger has been widely studied and critiqued, and it has often been used as a lens to examine the phenomenon of immigration in society. In Simmel’s seminal essay on the stranger, the stranger, like a field researcher, enters a local setting and stays a while (Simmel, 2006). Like the stranger, the field researcher’s position in the group is determined by their not-belonging. Moreover, like the researcher, Simmel’s stranger is open-minded. The stranger approaches the group with impartiality as she/he is not radically constrained to their uniqueness.

Nevertheless, detachments do not involve indifference but rather a structured involvement consisting of distance and nearness. Further, the stranger brings qualities into the group’s setting, and the outsider/insider encounter is positive because of the strangeness. In Simmel’s essay, he describes the stranger with a “specific attitude of “objective” (Simmel, 2006, p. 2) and can win confidence in the setting; there is no mention of curiosity. Simmel’s stranger is described as objective as he is not belonging and is a confidante but not inquisitive. Denzin & Lincoln (2014) focus on researchers doing fieldwork in unfamiliar settings and the dialogue between Indigenous and critical scholars. They call for research strategies that develop inclusive and collaborative research practices. Denzin et al.’s perspective implement collaborative, participatory, and performative inquiry. It emphatically aligns research ethics with the politics of the oppressed, with a politics of resistance, hope, and freedom (Denzin & Lincoln, 2014).

Nonetheless, we were curious and strangers in our respective research settings (K. A. Perry & Arnfjord, 2019; Rasmussen, 2021; Rasmussen & Olsen, 2020). Through exploring two different empirical studies in Greenland, we aim to illustrate aspects of the research processes that lead to a better understanding of fieldwork processes. While we are not strangers to our respective research fields, we are strangers to Greenland and the settings we entered. Moreover, being curious means, we have the desire to discover new knowledge in our respective research fields. Consequently, in the paper, we add ‘curious’ to the stranger analogy and henceforth refer to ourselves as either researchers or ‘curious strangers’.

This article taps into the methodological discussion when researching unfamiliar places and focuses on the researcher’s role in studying social and cultural environments. We discuss when outsiders conduct studies in unfamiliar contexts (e.g., families, villages, communities, corporations). This article aims to strengthen the methodological considerations when undertaking fieldwork in unknown settings. The paper suggests a way forward to rethink research in unfamiliar places by adopting the position of a curious stranger. We add to the discussion by considering how we encountered and embraced the interactant’s input while doing fieldwork. Thus, the purpose of this article is to critically examine the empirical endeavour when doing fieldwork in new settings. Many perspectives can be found in the literature to help illustrate and qualify fieldwork processes. To this aim, we employ Mead’s (1934) concept of reflexivity and Simmel’s The Stranger concept to help us understand these critical fieldwork encounters. These perspectives help illustrate how the researcher builds a reflexive practice as the fieldwork progresses.

The Median perspective has gained improved interest in postmodern writings, where researchers continue the work of elaborating the theorizing in various areas and issues. For example, Dionysiou and Tsoukas draw on symbolic interactionism and show how “role taking” (Mead, 1934) is an essential process through which routines arise and recur. Exploring micro-processes in a Median framework explains routine creation as a collective accomplishment of repetitive action patterns (Dionysiou & Tsoukas, 2013). Through their adoption of Mead’s work on the relationship between the “I” and the “me”, Hatch and Schultz show an innovative way of organizational analysis. They show how identity expresses cultural understandings through symbols (Hatch & Schultz, 2002). By drawing on Dewey and Mead, Simpson and Marshall develop a theoretical position that integrates emotion and learning. Simpson and Marshall propose an explanatory mechanism that frames emotion and learning as mutually forming and informing practices that emerge from social engagement and transactional meaning-making (Simpson & Marshall, 2010). Finally, Simpson (2010) proposes a view of practice that draws primarily on Mead’s theorizing. Simpson argues that this perspective offers a “holistic approach to practice, which challenges the dominance of those ‘rational actions’ and ‘normatively oriented action’ theories” (Simpson, 2010, p. 1330).

The studies mentioned above show how the Median perspective offers a critical approach when wanting to study social interaction among people in the social world, where the researcher takes a particular engaged position. Common among the mentioned studies is that they have brought the Median perspective to the centre of their qualitative analysis and applied it to empirical studies, focusing on examining, understanding, and attempting to explain empirical phenomena in concrete social situations.

The two cases are very different in their theoretical and practical interest. The commonality is that they occur in a less familiar setting – Greenland. The cases illustrate detailed empirical descriptions of particular situations of how the researcher, as a curious stranger, engages with the empirical world curiously and distinctly. Thus, the cases illustrate and serve “as a distinct experiment that stands on its own as an analytic unit” (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007, p. 25). The approach reported in this paper is different from grounded theory, which fails to recognize the embeddedness of the researcher and thus obscures the researcher’s considerable agency in data construction and interpretation (Charmaz & Bryant, 2007). Instead, the empirical data shows the importance of understanding the embedded dynamics of complex relationships in the settings under focus. Therefore, we argue that the abductive approach (applied here) has the potential to capture and take advantage of both the empirical world and the theoretical propositions—the research aimed at developing a theory instead of testing it. Thus, “The story is then intertwined with the theory to demonstrate the close connection between empirical evidence and emergent theory” (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007, p. 29).

Moreover, the perspectives above shed light on the researcher’s position in the field. Further, the concepts helped us collaborate with interactants during fieldwork, which empowered us to change and qualify the research direction. We seek to understand how reflexivity can illuminate and advance the research process. We aim to conceptualize a practice for the research process of the curious stranger (Simmel, 2006) based on Mead’s (Mead, 1932, 1934) concept of reflexivity.

The article addresses the research question: How does the researcher, as a curious stranger, engage in reflexive interactions in unfamiliar settings?

The article is structured as follows. Upon elaborating on the theoretical debate on dilemmas in fieldwork and reflexivity, the article proceeds with thick descriptions of Perry and Rasmussen entering their fields. Finally, based on the theoretical framework and empirical insights, we develop a discussion highlighting how a reflexive research practice can be developed based on a curious stranger’s perspective.

Background and Methodological Considerations

Fieldwork as a research activity is not without controversy, e.g., Humphrey’s 1975 study of the ‘tearoom’ trade (Humphreys, 1975), and has given rise to many discussions on the fieldwork process. Fieldwork is considered an evolving, fluid, and ever-changing enterprise. Despite their outset, all research projects can change course or fold due to challenges or unforeseen circumstances. Fieldwork involves gathering observations partly through participation and various types of conversational interviews. When undertaking fieldwork, understanding social interaction is crucial as the researcher must establish relations within a setting and build and maintain trust throughout (K. Perry, 2012).

The reflexive feature of field research infers an understanding that the researcher is part of the social world(s) under focus (Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994). Reflexivity is a widely used term in qualitative research and has been around for decades (Alvesson et al., 2008, 2017; Mead, 1934). Reflexivity implies a change in how we understand data and data collection and requires the researcher to regularly have an internal dialogue that examines what they know and how they know what they know. In other words, reflexive means the researcher has a continuing dialogue with themselves and the interactants. Reflexivity involves an awareness that the researcher and the field mutually impact one another continually during the research process. Hence, reflexivity concerns an active process whereby the researcher continually revisits their sense-making and considers the factors that shaped their understanding throughout the research process (Blumer, 1969; Mead, 1934; Weick, 2002). The reflexive researcher does not merely report findings as facts but actively constructs interpretations of experiences in the field and then questions how these interpretations occurred (Hertz, 1997; Maanen, 1988; Saukko, 2003). This process results in intuitive knowledge that gives insights into the workings of the world and knowledge production (epistemology). To further the discussion about reflexivity in the research practice, we construct our theoretical position around Meads (1934), thinking of how all practice arises in the relational gesture and conversation response. The relational dynamics of conversation lie at the very heart of Mead’s argument; through social interactions, we become reflexively aware of ourselves. At the same time, we can influence the meanings inferred by others (Mead, 1934).

Mead’s perspective is concerned with neither beginnings nor endings, as it focuses on the continuous unfolding of experiences in the present moment (Mead, 1934). Symbolic interactionism explains social relations as interactive, complex, and ongoing (Blumer, 1969; Mead, 1934). Following Mead, the self has the reflexive capacity, which is the effect of the internalization of interaction with other human beings (Mead, 1934). Through interactive processes, people become socialized and form mutual expectations of joint actions. In other words, social interactions are processes of adjusting and changing meaning. Mead points out that the self cannot exist without the other and explains that the self forms through socialization with others (Mead, 1934).

Thus, reflexivity occurs through the researcher’s intuitive reactions, active roles, and field relationships. Reflexive processes are interactive and social, and the self depends upon the existence of symbolic forms of interactions to emerge and develop reflexive experiences (Blumer, 1969). Based on reflexivity, experiences are modified and reacted upon by the self.

The social processes are the experiences of participants involved in them, which enable the individual to take the attitude of the other toward himself and change their perception. Mead describes this process in the following:

“He becomes aware of his relations to that process as a whole and the other individuals participating in it with him; he becomes aware of that process as modified by the reactions and interactions of the individuals – including himself – who are carrying it on” (Mead, 1934, p. 134).

When the process of reflexivity occurs, individuals become self-conscious and aware of their relation to that process and the others taking part in it. They become aware of the process as changed by the reactions and interactions and the other individuals who experience it. What is understood by Mead’s suggestion is that reflexive processes enable us to be self-aware of the context and aware of the context of others, e.g., the research field. According to Mead, the essence of the self is its reflexivity (Mead, 1934). Mead considers the self a process that constantly shapes and reshapes through social interaction. Thus, the self develops through the internalization of the generalized other. Through the concept of the generalized other, Meads describes the process where we, based on interaction, act as social beings and learn how to adapt to the norms of society. It is in these social processes that we influence one another and have the chance to learn and change our thinking:

“It is in the form of the generalized other that the social process influences the behavior of the individuals involved in it and carrying it on, i.e., that the community exercises control over the conduct of its members, for it is in this form that the social process or community enters as a determining factor into the individuals thinking” (Mead, 1934, p. 155).

Thus, when individuals engage in role-taking, they seek solutions to problematic situations by taking the role of others. Taking the role of the other is seeing the world through another’s eyes. In order to learn, human beings must be able to take the perspective of others. It is a process in which participants view themselves from the standpoint of others and consider alternative actions from the standpoint of others.

Mead emphasizes the intuitive nature of human behaviour (Mead, 1934, p. 136), and describes reflexivity in terms of an ongoing dialectic between the “I” and the “me”. Thus, the tension between the “I” and the “me” creates reflexive interactions. When socialization takes place, people adjust their behaviour through the inner conversation of the “I” and the “me,” where the acts of the “I” and the emerging attitudes from the others enter the “me” (Mead, 1934). According to Mead, the “I” responds to present social influences, while the “me” is related to previous social interaction experiences over time (Mead, 1934). Through an inner conversation between the “I” and the “me,” we can imagine ways to solve problems based on previous experiences. Mead argues that the acting “I” represents the socialized aspect of the self, whereas the reflexive “me” represents the inner reflexive self. The ongoing reflexivity between “I” and “me” is a kind of ongoing self-communication based on previous and present experiences. The reflexivity between “I” and “me” enables various perceptions of experiences to be considered. The “I” becomes the explorer who undertakes actions of inquiry.

Following Mead, reflexive processes enable us to be self-aware of the context and the context of others. Thus, it is possible to adjust our understanding of ourselves within this process and to change and evaluate our actions.

Consequently, researchers can adjust their understanding of the self within the fieldwork process and change and evaluate their meanings and actions. During this reflexive process, described as the “turning back of the experience of the individual upon himself” (Mead, 1934, p. 134), the researcher re-interprets fieldwork experiences from a new perspective in a process that can change understandings of the phenomenon of study. Subsequently, it is a particular way the researcher develops the practice. The reflexive “turning back experience” in fieldwork provides access to new understandings delivering explanatory abstractions about the field of study. It provides a basis for studies seeking to explore social interactions.

Throughout the research process, questions and general inquiries are formed by the empirical data and theoretical input and qualified as an abductive, e.g., intuitive and interpretive research process (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2009; Mead, 1934). As perceptions changes, the inquiries and research questions change accordingly. This way of thinking about research enables the researcher to overcome objective understandings. When the self is continually under construction, researchers experience this when participating in social interactions related to the study phenomenon. Attention to transforming the researcher’s “me” can provide genuine knowledge of the researcher’s context. So, the reflexive “turning back” in research provides access to new understandings as long as they do not lose sight of delivering explanatory abstractions and do not just report individual experiences as problematized by Yanow (2009). Turning back on oneself is a continuing process when undertaking research. Essential to this is “the scientist’s method and attitude that he accepts his findings just in their contravening of what had been their meaning, and as real to in independence of whatever theory is advanced to explain them” (Mead, 1934, p. 118).

Researchers can develop a reflexive fieldwork practice through a conscious and continuous process that gives a new mindset to fieldwork. Reflexivity empowers researchers to recognise the influence of interactants and the choices made during fieldwork.

Fieldwork in Unfamiliar Settings

The following empirical sections consider critical moments from Perry and Rasmussen’s fieldwork projects. As well as introducing the empirical settings, we make sense of critical fieldwork moments. The following sections adopt a ‘Thinking Note’ style, giving the reader research-based insights, understandings, and considerations.

The thick descriptions sketch out the contexts in which the research takes place. Writing up the thick description as thinking notes helps the reader understand the context in which the observations occur and the dynamics when the curious strangers, aka Perry and Rasmussen, enter the unfamiliar settings.

Study A: Tasiilaq

Tasiilaq is located on the island of Ammassalik in Eastern Greenland and is about 100 km south of the Arctic Circle. In Tasiilaq, nature is the all-dominating force and considerably impacts daily life. Periodically Tasiilaq is hit by ‘Piteraq.’ Piteraqs are downslope windstorms that hit southeast Greenland with wind gusts reaching over 300 km/h and temperatures falling beneath -20°C. Piteraqs are a danger to people in Tasiilaq and the surrounding settlements.

Located close to the Sermilik inlet (fjord) and surrounded by steep jagged mountains, Tasiilaq becomes isolated from the rest of the world for some months of the year. Ships can only reach Tasiilaq for two or three summer months because of closing ice, and the severe weather conditions limit helicopter flights. Because of its geographical placement, the language and culture in East Greenland are unique. Tasiilaq has a population of approx. 2,000 inhabitants. Ammassalik refers to the district that includes Tasiilaq and five settlements (Kulusuk, Sermiligaaq, Kuummiut, Tiniteqilaaq / Tiilerilaaq, and Isertoq). There are almost 3,000 inhabitants in the district of Ammassalik. In 2009, Greenland’s municipalities underwent a fusion process and fused into four municipalities. Organisationally the municipality of Tasiilaq was merged with Nuuk (approx. 700 km from Tasiilaq), becoming the large municipality of Kommuneqarfik Sermersooq.

Photo: Tasiilaq, Eastern Greenland.

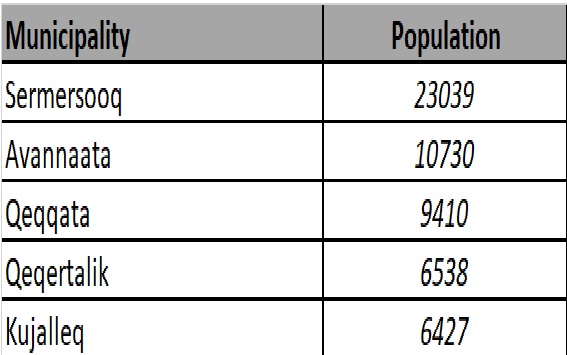

On January 1st, 2018, Greenland divided into five municipalities: Kujalleq, Kommuneqarfik Sermersooq, Qeqqata Kommunia, Municipality Qeqertalik and Avannaata Kommunia. The municipalities are part of the state and the political system in Greenland. As in similar welfare states, municipalities in Greenland solve a wide range of societal issues that impact the lives of citizens. Everything from providing child daycare, social housing, social services, education, administrating social security benefits, and the complex labour market sector as well as helping children in need of support and protection. Every local authority has an elected council, which allocates the resources within the municipality. However, the political majority in power in the individual local authorities predominantly determines the local policies and services available to the local community. Therefore, the municipalities’ areas of responsibility often require knowledge of local conditions and support from citizens in the area.

The Empirical Work in Tasiilaq

In April 2019, Kevin Perry was at the University of Greenland in Nuuk (Ilisimatusarfik), preparing to undertake preliminary field research in Tasiilaq, some 700 kilometres away, about homelessness, starting in early May 2019. The trip primarily aimed to investigate homelessness in Tasiilaq through observations and input from local authority employees and citizens. In many respects, the field researcher researching unfamiliar settings has similarities to Simmel’s ‘Stranger’ concept. Like the stranger, the field researcher is free to change location, which gives an advantage over being fixed in one place – the activity of ‘wandering’ (Simmel, 1908). Wandering is fundamental to Simmel’s ‘Stranger’, which researchers have in common. However, unlike Simmel’s Stranger, the field researcher is not the wanderer ‘who comes today and stays tomorrow’. Instead, the field researcher is the curious person who wanders into an unfamiliar setting and stays a while but will eventually leave. Nevertheless, like Simmel’s Stranger, the field researcher’s position in the new context is characterized by him or her not belonging to the context and bringing qualities into the setting that do not derive from the context.

Before departing Nuuk, I made some interview appointments with relevant civil servants in Tasiilaq who potentially knew about the town’s homelessness situation. Moreover, I posted information about my visit, including its purpose (looking at homelessness) and my contact information to the Tasiilaq Facebook group. In the post, I asked parties interested in meeting in Tasiilaq to contact me. As a result, the Facebook post generated three contacts who agreed to meet in Tasiilaq.

I departed on a two-propeller Dash-8-200 from Nuuk on May 1st, 2019, heading to Kulusuk, which takes approximately one hour and forty minutes (depending on the headwind). After a two-hour stopover in Kulusuk, I departed onboard a Bell 212 helicopter towards Tasiilaq, usually a twenty-minute flight. Luckily, the weather was fine, and both flights were uneventful and on time. After grabbing my bag at the heliport, I got a lift to Hotel Angmagssalik by a shuttle SUV that picks up and drops off hotel customers. Even though it was May 1st and most of the snow had disappeared in town, it was spectacular to look through the back of the SUV window and see the icebergs in the inlet (fjord) as we drove up the long steep hill.

After checking into the hotel and settling into my room, I walked down the long steep hill into town to explore. While walking down the almost vertical drop, some locals passed on the other side of the road heading up the hill. Whenever I encountered people on my journey into town, they greeted me by waving or saying hello/ hi (or a combination of the two). It was probably evident to the passers that I was an outsider (stranger) because of my appearance (skin colour & clothes). Moreover, in small communities, most people often know others or know who others are in town.

I returned their greeting by smiling, waving, and saying hello. Also, while walking down the hill, I observed that many wooden houses and other buildings appeared dilapidated and needed reparation and a few coats of paint. Finally, when reaching the bottom of the hill and crossing a small bridge, I reached the main drag leading towards the town centre. I noticed a lot of steep hills in the town, but not as steep as the hill that leads up to Hotel Angmagssalik. While walking around town, I familiarised myself with the layout of the land and located some of the addresses where I should undertake interviews the next day.

The following day after breakfast in the hotel, I headed down the long steep hill into town for my first interview.

I met all the interviewed persons with an outstretched hand and a smile. Moreover, prior to the interviews, during the interview briefing stage, I engaged in small talk with interviewees about photos on their desks or other artifacts in their offices. Moreover, throughout the interview encounters, the participants seemed interested in me as a person. The curious stranger concept seems to be a double whammy. Not only did I present myself as a curious stranger by inquiring about the interview persons’ office artifacts, but the interviewees also became curious about the stranger before them.

Remarkably, during the first two interviews and post-interview debriefs, the interviewees eagerly talked about a T.V. documentary concerning child abuse and neglect in Tasiilaq (to be shown the following evening). Both interviewees eagerly suggested that I watch the documentary. They expressed that the broadcast would be provocative as they knew the participants. Moreover, there were many child abuse and neglect cases in the town. Although my primary research focus was on homelessness, the employees’ insistence on watching the documentary made a striking impression. As one interview person expressed while mulling over homelessness in the town:

“There are very few homeless in Tasiilaq. Well, we do not have anyone sleeping rough on the streets. Many [people] do not have their own address … often live with family or friends in small townhouses. We know of cases where twenty people or more share the same house. I have been in houses where twenty or so mattresses lay in the corner of the front room. Often family and friends move to Tasiilaq from the settlements and have nowhere to stay. We are family people, and we do not turn family away. So, we do not have absolute homelessness in the town. While you are here, you should look at the situation of children in the town. Many live with violent parents with drunk parents and are poorly treated and neglected. Some children attempt suicide, and some succeed. If you want to know more about it while you are here, talk to [name]. There is a broadcast about the town and the situation for children [on T.V.] … you should see it [strongly emphasised]” (Civil Servant A – May 2019).

The framing of the T.V. documentary was something that the participants did of their own volition. When participants undertake intentional behaviour during interviews and change the agenda, this is known as “breaking frame” (Goffman, 1974). Frames inform and control activities allowing participants (and often onlookers) to make sense of the situation (ibid). The interview situation is an activity framed by a set of often unspoken rules and expectations; if an interactant attempts to change the interview’s direction, this is a breaking frame. Breaking the frame involves changing the events in the frame (interview) in another direction:

“When an individual participates in a definition of the situation, circumstances can cause him suddenly to let go of the grasp the frame has upon him, even though the activity itself may continue” (Goffman 1974, p. 349).

Breaking frame involves individual agency triggered by the situation, which causes the individual to break frame. Before encountering these employees, I was oblivious to the up-and-coming documentary. I believe these interviewees deliberately ‘broke the frame’ to change my focus and influence the situation. Looking back at these two encounters, they became pivotal and changed the focus and the direction of my research in Tasiilaq.

Unfortunately, there was no ‘complimentary’ WIFI at the hotel, so I invested three hundred Danish Crowns in buying a WIFI connection for the following evening. When it aired, the DR. (Denmarks Radio) was a provocative journalistic piece stating that many children and young people in Tasiilaq grow up in grossly abusive environments. Additionally, the municipality had critical shortcomings in safeguarding and protecting children. Consequently, after watching the controversial broadcast, I expanded the interview guide to include questions that tested the claims made in the documentary.

While mulling over the powerful messages sent in the documentary and thinking about the two civil servants’ tenacity in nudging me to watch the documentary, I decided that while in the remote community, I had an obligation to investigate the situation. Before entering academia, I worked as a social worker with young people. I came across many young people living in abusive settings during that period. Subsequently, I did everything within my capacity as a social worker to help and support these young people. Therefore, because of my prior experience in social work coupled with the tenacity of the two interviewees, I felt obliged to investigate the allegations advanced in the documentary.

Consequently, I expanded the interview guide to include questions that tested the claims made in the documentary. While expanding the interview guide to include probing questions about the validity of the documentary, it still included themes and questions concerning homelessness in Tasiilaq.

Armed with my updated interview guide over the subsequent week, I interviewed several civil servants who could give first-hand accounts of the situation in Tasiilaq concerning the plight of children and municipality safeguarding practice. My approach when meeting the other interviewees was consistent with that reported above. Moreover, the other interviewees were interested in the curious stranger who sat before them and asked curious questions.

Because of watching the documentary and expanding the interview guide, I gathered unique data that mostly validated the claims made in the documentary.

Later, a colleague and I published an article in a journal examining Greenlandic issues. The article compared the claims made in the documentary against first-hand accounts (qualitative data) by frontline municipal employees who work with safeguarding children. In addition, the article scrutinized some of the challenges faced by the employees through a social policy lens.

Specifically, the paper explores the referral reporting procedure in the municipality and the lack of local decision-making competencies.

The article concluded that a significant minority of children and young people live under challenging conditions. Moreover, there were similarities between the claims made in the DR TV broadcast and the experienced reality in Tasiilaq. The data revealed a large cleft between the employees in Tasiilaq and the decision-makers in the capital Nuuk. The decision-making cleft hampers social care practices at the local level and increases case processing time. The data also revealed two incompatible I.T. systems at play that only add to the protracted case processing by giving extra challenges for the pressured municipal employees in Tasiilaq.

Study B: Middle management activities at Greenlandic fish factories

The context for this part of the study is a large state-owned fish factory in Greenland. Fishing is Greenland’s largest industry, and the general economy is reluctant to an influential fishing industry (Grønlands Økonomiske Råd, 2021). The company has factory facilities all along the coasts of Greenland. The factories in Nuuk and Maniitsoq set the empirical frame for this study, both located right at the wharf. Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, has approximately 16,000 inhabitants. Maniitsoq, slightly north of Nuuk, has approximately 2,600 inhabitants.

The Nuuk fish factory has between 12 and 40 employees, and the factory in Maniitsoq has between 20–100. Thus, the production facilities in Maniitsoq are also more extensive and more automated. At the same time, however, the fish production processes in both factories are pretty similar, and the way work is organized is based on the same production line. This meant that when I arrived in Maniitsoq, after having spent a week in Nuuk earlier, the processes and activities were somewhat familiar, and I felt less like a stranger than I had when first arriving at the Nuuk factory. At the Nuuk factory, I spent some time getting familiar with the production processes, the jargon, and even the fish.

The fishermen unload their boats at the wharves, which come in various sizes, from small dinghies to mid-sized fishing boats. Fish processing is seasonal and weather dependent, meaning that sometimes there needs to be more fish while there are not enough employees at other times. Workloads and activities at the factory are hard to predict because they depend on what fishermen bring in – cod, redfish, halibut – or in bad weather, nothing. Fish factory workers are paid mainly by the hour, and when there are no fish, there is no work. Given the seasonality of the work, the number of employees varies.

At both factories, a Factory Manager oversees the production plant. The workforce consists mainly of unskilled (blue-collar) workers whose workload is often standardized, simple, and monotonous. Middle Managers at the factory are also unskilled but often have many years of experience or a proven track record of stability. They organise the workflow and function as the link between the Factory Manager and employees. In addition, middle Managers coordinate activities based on estimated sales and the fish traded. Most Middle Managers have attended in-house collaboration, leadership, and quality control training.

Activities at the factories are organised among various departments. For example, in the Trading Department, fish are traded in by local fishermen and prepared for the production line. At the Production Department, fish are cut up, filleted, and frozen. Moreover, fish are packed and made ready for shipment at the Packing Department. The Quality Department is constantly monitoring quality, procedures, and hygiene. Quality control is a significant issue at the factory. A Quality Manager and assistant constantly test the quality of the fish and factory hygiene and monitor employees to ensure compliance with quality guidelines.

The Trading Manager is the primary contact for the fishermen, and his office is by the factory entrance. This area is, in many ways, the heart of the factory. It is where large and small boats come in, and it is the epicentre for most information. In Nuuk, the Trading Manager is in close contact with the fishermen who call him on their way from the shore to report where they have been and what they have caught. Fishermen on the larger fishing boats are given a time slot for arrival and unloading. The small dinghies can approach the wharf when a time slot becomes available. Information about what is coming in is immediately recorded and shared in the internal system, accessible for the headquarter, sales, marketing, and much more. The Trading Manager has a close and vital relationship with the fishermen at sea, and this relationship is critical for planning and coordinating production activities.

The empirical work at the factories

Rasmussen’s research at the fish factory partly illustrates the reflexive inquiry when she, as a curious stranger, undertook fieldwork focusing on the management activities at two Greenlandic fish factories. The two sites were selected due to somewhat similar setups and their geographic accessibility (which is not always the case in Greenland). The primary language at the factory is Kalaallisut (Greenlandic), but most employees speak Danish. This language barrier, for the Danish-speaking researcher, was handled differently at the two factories. In Nuuk, most leaders and employees speak Danish, but other employees functioned as interpreters to handle the linguistic challenges, which did occur at times. In Maniitsoq, the situation was different. Fewer people speak Danish, and since I knew this beforehand, I arranged for a graduate student from the University of Greenland (Ilisimatusarfik) to come along to help with translations when needed. To prepare for the task, the graduate student and I thoroughly discussed the research interests. The student also had a logbook, and at the end of each day, we compared notes and discussed our experiences.

I followed, shadowed, and worked beside leaders and employees at the fish factories for a week at each site. During the two weeks at the factories, I took part in the workload, attended meetings, had formal and informal conversations with managers and employees, and had lunch and breaks in the canteen, joining everyday conversations. Puzzlements about daily activities occurred when we were in the middle of filleting fish, packing fish, conducting quality control, or just drinking coffee in the canteen. Thus, conversations and interviews were based on an open structure, and questions addressed (a) the dilemmas the managers are facing, (b) how they engage and include employees’ perspectives in daily tasks, (c) relations to peers, and (d) how they think about leadership. Most conversations and interviews took a reflexive form, where we discussed puzzlements, I had noted, but also managers asked how I experienced particular situations. I discussed with Maintenance, Quality, Production, Factory, Trading, Shop Steward, and various factory employees. All interviews, conversations, and observed meetings were turned into approximately 75 pages of electronic field notes, including large and small details of observations, meetings, and informal talks. These fieldnotes include descriptions from observations but also transcripts from small conversations and interviews with leaders and employees describing how the daily work life unfolds at the fish factory. In addition, photos were taken at the factory, reminding me of the various activities and the settings observed. A few of these photos are used in the article to enhance understanding. Participants are anonymized throughout the paper to protect their privacy.

The following is an example of an empirical situation that unfolded at the factory in Maniitsoq:

“Wednesday, there was a breakdown on the conveyor belt. I was filleting fish at the time, but since the conveyor belt was not moving, the employees were out of work. Some started cleaning up, others helped in the packing department, but most were sitting, waiting for the belt to move. The middle managers were trying to solve the problem at the conveyor belt” (Based on an extract from logbook).

When the situation was solved, Rasmussen revisited the situation with middle managers and employees, asking questions such as: What happened? What do you think of the situation? How was the situation of leadership or the lack of it? Who was active in the situation? How do you collectively attend to these kinds of situations? In this way, Rasmussen’s understanding of the situation became qualified by collective reflexions, which qualified the understanding of the particular situation.

Being at the fish factories gave me access to informal and inside knowledge. Curiously, I attempted to engage with different situations and ponder upon the meanings of experiences. I was amazed and touched by how eager employees were to share their experiences. I stayed curious about stories unfolding at the fish factory and more personal stories about how working influenced employees’ personal lives.

The following empirical example introduces a critical activity at the factory: trading fish in the Trading Department. Here the scene is set for the activities to follow at the production facilities. If there are no fish, there is no work:

“The Trading Managers’ office has a window facing the wharf and a window facing the entrance to the factory. Not much gets by the Trading Manager. This area is, in many ways, the heart of the factory. It is where boats, large and small, come in, and it is the epicentre for most information. The Trading Manager is in close contact with the fishermen who call him when heading to the factory. They report where they have been and what they have caught. Fishermen on the larger fishing boats are given a time slot for arrival and unloading. The small dinghies can approach the wharf when a time slot becomes available. Information about what is coming in is immediately recorded and shared in the internal system (e.g., headquarters, sales, production). The Trading Manager has a close and crucial relationship with the fishermen at sea, which is critical for planning and coordinating production activities. All activities in the trading office are critical for the factory in general. When the fishermen bring in their catch, the trading office provides them with ice and bait.” (Based on an extract from the logbook).

The activities of the Trading Manager are essential, and he crosses the boundaries with the other departments to give an overview of the many related activities. For example, one day before lunch, I asked the Trading Manager how I would act if I were his double (Nicolini, 2009). I guess he found the question a bit strange, but after finishing lunch, he gave me the following explanation:

“To be my double, you should start the day by finding out who showed up for work. After that, you must check production papers from the previous day and ensure that all the paperwork is in order and has been shared with the appropriate departments. Next, we share all figures and numbers to know the amount of fish incoming and the amount that becomes transferred to production.

After that, you must check emails and ensure that morning and evening teams are aligned and ready for their tasks. Then you must email the people involved in the day’s tasks and explain their assignments. Furthermore, an essential part of this is to delegate tasks to team leaders. They play an essential role in handling daily tasks. You should have regular meetings with team leaders because this creates an overview.” Moreover, he added that you should include different team leaders and employees in the paperwork, which he claims creates collaboration and insight into the trading processes.

The context of fish factories in Greenland is a non-usual site – an unfamiliar site for the researcher and many readers. However, the characteristics of this case would be instantly recognizable to people working in most production plants. The empirical study shows how leadership practices emerge in collaboration with various organizational actors. We see how middle managers’ activities include a solid focus on quality procedures and, at the same time, leadership activities as bricolage organizing the workflow based on sensitivity to local situations.

Discussion: Conceptualising a Practice for the Research Process of the Curious Stranger

Perry and Rasmussen stayed close to the study practice during the presented cases. Consequently, the research site and the exciting questions evolve between the researcher and interactants. Discussing a stranger’s engagement in the field does not necessarily imply undertaking research in remote places with Indigenous Peoples. The term can apply to researchers working in a wide range of semi-public settings. At the heart of research, practice is the curious stranger who is both accessible and participating in activities and, at the same time, distant, creating different perspectives on the phenomenon of study. After the curious stranger has gained access to a relevant setting to gather data, many dilemmas can be faced and tackled. One dilemma concerns the researcher building trusting relations with locals and maintaining trust. Another dilemma concerns researcher-embeddedness or the extent to which the curious stranger assimilates into the research setting. Going all in, known as ‘going native,’ can cause setting blindness. ‘Going native’ refers to the phenomenon that the researcher incorporates the studied group’s traditions, practices, worldviews, and values, i.e., to become like the people under focus (Alvesson & Einola, 2018; Atkinson & Hammersley, 1994; Maanen, 2011). If the curious stranger spends extended periods in settings, there is the risk of losing the stranger’s position and curiosity. After a prolonged period in the unfamiliar setting, it becomes familiar, and it can be challenging to maintain a distant and curious approach. The original theoretical starting point may not fit the curious stranger’s new understanding of the phenomenon.

Consequently, a conversational, responsive process drives the meaning of the situation and course of action: a conversation of gesture (Mead, 1934). Mead advances this as the responsive sense of reflexivity generated through responsive interactions and adopted in this paper.

Summing up, reflexive practice is a creative, nonlinear activity whereby we, as curious strangers, analyse and evaluate our experiences allowing for deeper insights and understanding of complex situations. From Perry and Rasmussen’s empirical examples above, it is noticeable that staying curious about situations, even when they seem somehow familiar, often turns out to include fascinating, surprising, and puzzling situations. The thinking notes evoke an impression of being in the settings in focus, of having contact with the conversational experiences. This way, the thinking notes are ‘thick inscriptions’ of particular unique situations. The thinking notes are the curious stranger’s selections and impressions, highlighting aspects of situations that the researcher thinks are important and relevant to write about, given the research setting. Describing what the researcher and the others in that situation are doing, saying, thinking, and feeling adds to the reflexive accounts. The thinking notes do not intend to mirror something ‘out-there’ objectively. Instead, they illustrate the researcher’s experience while inviting the reader to the unfamiliar setting. The thinking notes are regarded as ‘raw material’ and serve as the basis for further reflexivity. Hence, the analysis and this reflexive interaction process is not a solo activity of the researcher but a collective activity, emerging in interactions close to the phenomenon of study.

Conclusion

In the above, we have discussed ways to strengthen the research practice by rethinking fieldwork from a curious stranger’s perspective. The curious stranger helps comprehend the ambivalent relationship between the observed and the observer. We argue that the concept of the curious stranger produces better local knowledge for analysis and a sensitivity to the rich empirical material we face when doing fieldwork.

We emphasize that reflexivity, one of professional creativity’s main characteristics, is an essential feature of the curious stranger’s research practice. Collective reflexivity become essential for relevant knowledge creation when doing research and represent a kind of reflexive practice. The curious stranger grasps situations that break with routine and ordinary activities and qualifies relevant understandings of the phenomenon of study involving new perspectives on theory and levels of analysis. Thus, in collaboration with the interactants, the researcher reconstructs an understanding of the empirical field, distinguishing this fieldwork method from less reflexive methodologies.

As we reflect discus lived experiences as strangers in the Greenlandic research settings, we realise how reflexivity and curiosity have informed our knowing. We realize how little we knew when we began. We engaged and immersed ourselves in various settings and stayed curious, which made us connect in new and more reflexive ways with people we met on our way. We have argued that Mead’s formulation of turning back the experience offers rich potential for conceptualizing and understanding what is occurring in empirical settings. Besides, this enhances theoretical sensitivity when shifting between empirically emerging themes and the literature to integrate findings reflexively in the analysis.

The distinction between ‘The Stranger’ and the ‘Curious Stranger’ is seeing beyond what interactants present during research interactions and distinguishing between ‘front & backstage’ (Goffman, 1959) and reaching backstage. The Curious Stranger approach methodologically provides a way to see the practice as it unfolds ‘backstage’ and opens for new and exciting questions to explore. The empirical activity is more than just collecting data about unfamiliar others. It involves the turning back experience, which qualifies to understand. The curious stranger is sensitive to the nuances of the field and their interpretations that might influence the outcomes. Reflexivity involves a more profound and broader understanding, involving more significant levels of sophistication and complexity.

References

Alvesson, M., & Einola, K. (2018). On the practice of at-home ethnography. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 7(2), 212–219.

Alvesson, M., Hardy, C., & Harley, B. (2008). Reflecting on reflexivity: reflexive textual practices in organization and management theory. Journal of Management …, 45(3).

Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive methodology: new vistas for qualitative research (Vol. 33, Issue 2). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Alvesson, Mats., Blom, Martin., & Sveningsson, Stefan. (2017). Reflexive leadership: Organising in an imperfect world / (Mats. Alvesson, Martin. Blom, & Stefan. Sveningsson, Eds.) [Book]. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Arnfjord, S., & Hovgaard, G. (2021). Samfundsvidenskabelig praksis – Arktiske perspektiver (S. Arnfjord & G. Hovgaard, Eds.). Greenland University Press.

Atkinson, P., & Hammersley, M. (1994). Ethnography and Participant Observation. In Y. S. Lincoln & Denzin (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (Vol. 1, Issue 23, pp. 248–261). Sage.

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. University of California Press.

Charmaz, K., & Bryant, A. (2007). The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Grounded Theory. Sage Publications Limited.

Denzin, B. N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2014). Introduction: Critical Methodologies and Indigenous Inquiry. In Y. S. L. & L. T. S. Norman K. Denzin (Ed.), Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies (pp. 1–20). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dionysiou, D. D., & Tsoukas, H. (2013). Understanding the (Re)Creation of Routines from Within: A Symbolic Interactionist Perspective. Academy of Management Review, 38(2), 181–205.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory Building From Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Goffman, Erving. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. (Erving. Goffman, Ed.; 2. impr.) [Book]. University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre.

Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2002). The dynamics of organizational identity.

Hertz, R. (1997). Reflexivity and voice. SAGE Publications.

Humphreys, Laud. (1975). Tearoom trade: impersonal sex in public places / [Book]. In Aldine. Aldine.

Maanen, J. van. (1988). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography (pp. 73–124). Taylor & Francis.

Maanen, J. van. (2011). Ethnography as work: some rules of engagement. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1), 218–234.

Mead, G. H. (1932). The Philosophy of the Present. Prometheus Books.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, Self, and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist (C. W. Morris, Ed.). University of Chicago Press.

Perry, K. (2012). Framing Trust at the Street Level (Issue March). Roskilde University.

Perry, K. A., & Arnfjord, S. (2019). Det er langt fra Tasiilaq til Nuuk – perspektiver på socialt arbejde på distancen. Tidsskriftet Grønland, 67(4).

Rasmussen, M. A. (2021). Middle managers practicing leadership. An empirical study of leadership at Greenlandic fish factories. Forthcoming.

Rasmussen, M. A., & Olsen, P. B. (2020). Ledelse i Grønland: COVID-19 bryder med kendte aktiviteter og rutiner i ledelsesaktiviteten. Tidsskriftet Grønland, 2, 85–91.

Saukko, P. A. (2003). Doing Research in Cultural Studies [Book]. SAGE Publications.

Simmel, G. (2006). The stranger. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87(1), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1516/2M30-7DK8-C2XU-R14Q

Simpson, B. (2010). Pragmatism, Mead and the Practice Turn. Organization Studies, 30(12), 1329–1347.

Simpson, B., & Marshall, N. (2010). The Mutuality of Emotions and Learning in Organizations. Journal of Management Inquiry, 19(4), 351–365.

Weick. (2002). Puzzles in Organizational Learning: An exercise in Disciplined Imagination. British Journal of Management, 13, 7–15.

Yanow, D. (2009). Organizational ethnography and methodological angst: myths and challenges in the field. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 4(2), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465640910978427