One of the shipping industry’s most systemic issues is the lack of regulation regarding Flags of Convenience (FOCs). Ships with FOCs “are ships registered under the maritime laws of a country which is not the home of the country of the ships; owners, because the country of registry offers low tax rates and/or leniency in crew and safety requirements.”[1] This lack of enforcement and regulation is made worse even worse for vulnerable environments such as the Arctic[2] In the Arctic and Sub-Arctic States, the International Maritime Organization and the Arctic Council face the challenge of controlling and regulating these vessels under foreign flags that transit through Arctic routes. According to the United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Art. 24, para 1(b): “[…] the coastal State shall not: discriminate in form or in fact against the ships of any State or against ships carrying cargoes to, from or on behalf of any State,”[3] meaning all flags shall be accepted unless it is proven that vessels do not comply with the international regulations in force at that time. Furthermore, as States considered FOCs are the largest carriers of gross tonnage in the world,[4] they play a pivotal role in decision-making and the creation of treaties and conventions established under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and other relevant maritime bodies. Therefore, the lack of good governance from these States is translated into the international shipping regulatory framework and then put into practice by the industry.

Introduction

Because of FOCs[5] ship owners have the flexibility to choose where to register their vessels based on cost, convenience and the international and domestic regulations that would govern their operations, including those that transit the Arctic.[6] “Nevertheless, this freedom is sometimes abused and somehow ship owners end up in the hands of flag states that are incapable of enforcing international and national jurisdictions over their ships. Once again, these failed flag states are what are referred to as the FOCs.”[7] To show this lack of transparency, the authors set about to register a ship through an FOC for a ship they did not own and also show data showing unregulated, non-transparent behavior via registration already ongoing in the Arctic. This contribution will follow two previous contributions to Nordicum-Mediterraneum as it “will use the definition of transparency provided by Rachael Lorna Johnstone and Hjálti Ómar Ágústsson, as these authors evaluate transparency according to the ease of accessing information and the quality of this information.”[8] Therefore, for the authors’ experiment, “transparency is evaluated according to the ease of accessing information, its quality, and the timeliness of disclosure.”[9] The authors also support the Governance for Sustainable Human Development, the United Nations Development Programme (“UNDP”) definition of good governance, which “defines good governance as, among other things, participatory, transparent and accountable as well as effective, equitable and as promoting the rule of law.”[10]

In Section II, the authors will briefly outline the current regime’s failure in controlling FOCs regarding criminal, environmental and labor standards. In Section III, the authors focus specifically on the good-governance criterion of transparency in three FOC countries when it came to registering a ship called the Stena Nordica: Liberia, Honduras and Panama. The authors compare these findings to the high-quality vessel registration of the Arctic state of Norway and how that relates to issues within the Arctic such as current violations within the Northern Sea Route (NSR) in Section IV. Section V will briefly consider three policy recommendations for the 8 Artic States of the Arctic Council to consider, and the authors will finish with a short conclusion regarding overall transparency findings.

Gaps in the Current Regime

“Use of open registers by the shipping industry is increasingly dominating global trade; over the last 50 years, shipping by vessels from open registers has been growing at more than ten times the general world economic growth rate. In 1970 21.6% of vessels were registered in open registries. By 2015 this had grown to 71.3% of the global fleet.”[11] Lack of safe conditions on board due to low amounts of regulatory policies, poor pay scales for workers and improper work schedules for FOCs allow inexpensive crews to be drawn from a global labor pool. Average annual labor costs aboard German container ships, for example, were reduced by over 74% by flagging out to FOCs in 1997.[12] In the deregulated FOC labor system, the total number of seafarers around the world has fallen as ships have been allowed to become much larger. There has also been a radical change in ocean labor’s ethnic composition, as crew members have been increasingly drawn from countries with relatively low wages and living conditions—leading to massive unemployment among unionized, high-wage seafarers from traditional maritime nations.[13] “Jail with a salary” has become a common figure of speech for work at sea in the FOC system.[14]

Environmental concerns also play a massive role in the current acts of FOCs. For example, the Deepwater Horizon’s registration was under the Marshall Islands,[15] a notorious FOC, causing quite a stir in the United States’ Congress, yet we saw no further restrictions on FOCs from this tragic incident.[16] Furthermore, the illegal nature regarding the activities of Liberia’s warlord and former President, Charles Taylor, was well documented as he was brought before the ICJ for war crimes, using ships on the Liberian Registry to move illegal goods, such as blood diamonds and illegal arms.[17] Even if such a behavior is known, enforcement is nigh impossible. “As is the case with flags of convenience in the mainstream shipping industry, the process of ‘reflagging’ enables a continuous circle of non-compliant behavior, as vessels are able to re-flag to a new register when the conditions imposed by their current flag, or the consequences of non-compliant behavior under that flag, become too onerous or restrictive. Similarly, if a previously non-compliant flag State decides to mend its ways and clean up its register, or to de-register vessels in order to reduce overcapacity, de-registering a vessel can export the problem, as the vessel concerned can simply find a new, less responsible flag State.”[18]

Registering of the Stena Nordica[19]

The Stena Nordica was chosen as it is a ship in which Author Thomas Viguier used to work on as a Merchant Marine Officer in 2015 while it was under the French flag. The vessel currently resides under the Bahamian flag, and thus being flagged under an FOC, made an opportune choice for the authors to have conversations about re-flagging without raising any eyebrows. The authors also chose this vessel as the Author knew the exact details of the vessel, allowing more detailed conversations regarding gross tonnage and net tonnage, as well as other important dates regarding flagging history and construction. Furthermore, Mr. Viguier had the chance to assist to the process of re-flagging the vessel from British to French flag, going through procedures, audits and formalities required to issue all the necessary certificates in order to obtain the right to sail the French flag. Furthermore, such procedures are highlighted by the IMO in its website section “Legal Affairs” under the article “Registration of Ships and Fraudulent Registration Matters”. However, given further considerations of the scope of this paper, the authors decided not to go too far down the path of full re-flagging for legal reasons. However, the countries selected represent an Arctic State, Norway, which is highly respected for its high standards in terms of flag state regulations, and two flags of convenience: Liberia and Honduras, with the second inextricably linked to Panama.

a. Norway

As all States, even if landlocked, have the right to enjoy the freedom of sailing the high seas and the right of innocent passage within territorial waters of foreign States according to UNCLOS,[20] the above considered States may constitute possible flags that may fly in Arctic waters. As will be shown infra, such FOCs are currently engaging in Arctic shipping in the Northern Sea Route (NSR). At the top of the safety rankings, the Norwegian Maritime Authority shows transparency and good governance, providing in their website all the regulations in force (both national and internationally) as well as all the legally required documents.[21] In addition, the following information may be found online: the organizational structure and employees’ contacts;[22] strict rules on the selection of Class Societies are applied, with Norway being the largest and most trusted one;[23]and fees are explicit and classified according to types of vessels, length and gross tonnage, which are fully related to the ship and are realistic according to the economic value of both the ship and the possible economic benefit.[24]Limitations are set clearly by law for trade areas, and the NIS has legal regulations and frameworks that will rule and explicitly designate the use of the registered vessel,[25]and all aspects of a ship’s life are covered, from construction[26] to scrapping[27] were also found online.

Norway’s Maritime Authority has a high level of transparency, given the easy access to all fees, documents, and requirements in a highly navigable website, even in English, therefore satisfying the ease of access and quality our information adopted definition of transparency. Using the definition of transparency as ease of accessing information, its quality, and the timeliness of disclosure,[28] the information was of high quality, immediately available, and available in Norwegian and English. Thus, Norway is one of the most transparent states in providing shipping registration data.

b. Panama and Honduras

Panama and Honduras are interwoven, as Honduras admitted that we would need to register the vessel with Panama Port State Control to have a Honduran flag. Despite this connection, the conversations’ outcomes were very different, and the information provided by both websites was not in accordance with the information provided on the phone.

For Panama, the names, contact information and pictures of the board members can be found, including their organizational structure. However, Panama shows a lack of transparency on the documents required to register a vessel. Point 4 on “Abanderamiento Regular” (Regular flag attribution) states the Dirección General de la Marina Mercante reserves its right to ask for further documents for the flag attribution.[29] On the very short phone call,[30] conducted in Spanish, Thomas Viguier spoke with two persons. The first was a female secretary who transferred our call to a man who spoke incomprehensibly and placed Mr. Viguier on hold. The hold was subsequently cut short. Therefore, we received no information for simply asking, “We would like to register a vessel under the international registry of Panama.” Again, using the authors’ accepted definition from Johnstone and Ágústsson, the authors classify Panama as non-transparent as the website was nearly inoperable, not all information was accessible in English, and even a native speaker could not gather more information on the phone. Furthermore, the authors could not confirm the information on the website provided was accurate, which was an issue for other countries.

On the opposite end of the spectrum of transparency, Honduras had an unwieldy website where very little information regarding the board could be found.[31] There was part labeled “lawyers” with no names in the organizational chart, yet Mr. Viguier learned on the phone call that these lawyers are on standby to sign off on any accepted registration for a low price equivalent to 300 USD.[32] Furthermore, there is a “transparency” box on the website that lead to another complex website where opposite information may be found (e.g., the name of the General Director on the Dirección General de la Marina Mercante is “Roberto E. Cardona”[33] and the name in the Transparency Website is “Juan Carlos Rivera Garcia.”[34] The website itself raised transparency concerns before the call was even commenced.

An additional red flag for transparency was information sharing. When the Authors attempted to share the website’s link on Facebook, they received a message saying the link was violating the Facebook Community Standards:

Picture 1

The three pillars of Facebook’s Community standards are authenticity, safety, and privacy.[35] Therefore, either the website itself was insecure, unauthentic, or was violating unique visitors’ data privacy. The authors’ thoughts are that the site was insecure as it was probably not willfully hiding authentic information or harvesting data but was a result of mere negligence in the website’s maintenance. Either way, that shows a lack of upkeep by the State and allows the system to be infiltrated. In this sense, the transparency was negligible. This negligible transparency has massive repercussions due to the its insecurity as it means that it is highly vulnerable to cyberattacks by individuals or groups, leading to stolen data, deliberate spreading of misinformation, or compromising the security of the ship database itself. All of these outcomes would not only affect the State’s ability to run an efficient shipping registry but could also lead to legal disputes due to lack of privacy concerns.

Thomas Viguier called the phone number provided on the website,[36] and he spoke in Spanish with a person[37] who, within 15 minutes, gave an incredibly cheap fee for a provisional registry of the Stena Nordica,[38] by merely taking the Gross tonnage as stated (usually the Net tonnage is used but requires specific documents to be found that are not publicly available), at around 20,000 GT, as the tonnage for calculations. The person gave us his private phone number to accelerate the process through WhatsApp, and his email. The fee was USD 8013.18 for 6 months. The only required conditions to get the provisional license were: The owner’s official documents accredited by a lawyer from Honduras (photocopy allowed and lawyer provided) and the Certification from the Class Society.

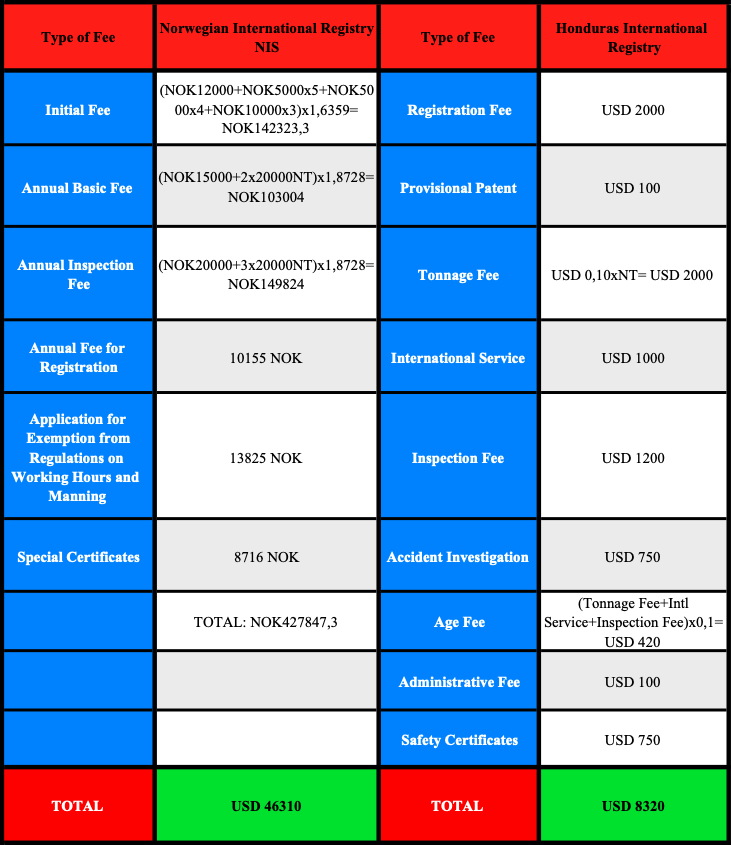

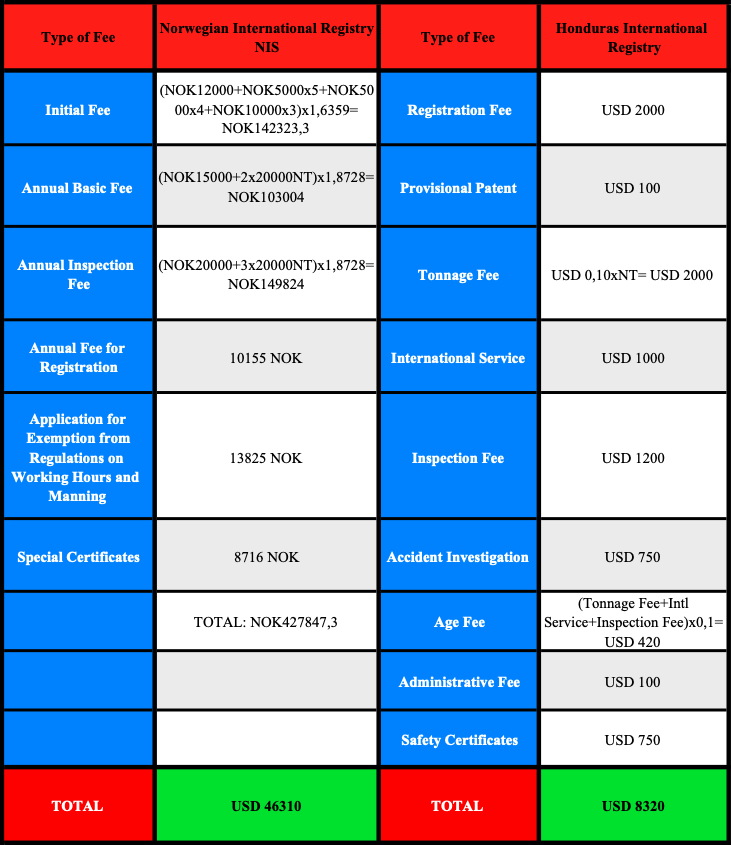

The representative told Mr. Viguier that the only delay and denial he could get was from checking the arrest file regarding the ship. Furthermore, in the official documents posted online, there is a clause we, as owners, can benefit from in which the owners receive a discount if the vessel is not arrested of up to 40%.[39] The provisional fee is 8013.18 USD, which is half the price to the registration fee of 16,000 USD under the Norwegian International Register (NIS), and is 82.7% cheaper compared to the whole year fee of 46,310 USD under the NIS during year 1. Table 1 illustrates the calculation of both fees for a 20.000 NT vessel.

Table 1: Fee Comparisons Between Honduran and Norwegian Registration

The calculated fee from Honduras Maritime Authority and the one was given on the phone call aligned. The Net tonnage given on the phone was slightly smaller, justifying the difference. The person also told us that they cooperate with Panama for their international registry, being able to register a vessel in Honduras via Panama’s Maritime Authorities.

There were other concerns on the call since our representative pushed very hard for a deal to get done and did not ask a single question besides the information needed to get the price, such as whether the ship was in working order or it had been arrested. There were no questions about who the caller was, where the ship was currently located or who the owner was. The authors conclude that if they had had the money on hand, they could have registered the ship in a very non-transparent manner given the information requested. Given the above, Honduras had a shocking lack of transparency and may even encourage borderline illegal behavior. While access to information was easy for a Spanish speaker, an English speaker would have struggled, based on the other authors’ attempts.[40] These low prices, the little information provided, as well as inoperable websites and preferential treatment for Spanish-speakers (at least anecdotally) shows that there is little transparency in the process given the adopted definition of transparency by the authors.

c. Liberia

Given that Liberia’s official language is English and provided that author Jonathan Wood is a New York-barred attorney in good standing, he called the Liberian Registry office in New York City,[41] hoping to achieve better results. He announced himself as a researcher for the University of Akureyri, attempting to fight the stigma of the term “Flag of Convenience.” The answerer, Claire Williams, said everyone is busy and would not speak with him, and she referred to their YouTube channel. When further elaborating on the research, she grew slightly warmer and provided her email address to make a formal inquiry. The Author made such an inquiry via email and followed up, yet never received any response. The Author reviewed online material and YouTube videos (which were thinly-veiled propaganda[42] and testimonials), finding accessible information in English; however, the forms such as in the case of Honduras and Panama were lacking. While language was not a concern for transparency, the ease of access of information was difficult, given the many offices Liberia uses, which is 24, and the timelines of information (of which there was none). Therefore, Liberia’s Registry was non-transparent, according to the authors based on their adopted definition given no information was provided, and the website itself provided no valuable information as it was a Kafka-esque experience to find a number to call to even register a vessel.

FOCs in the Arctic: A Growing Concern

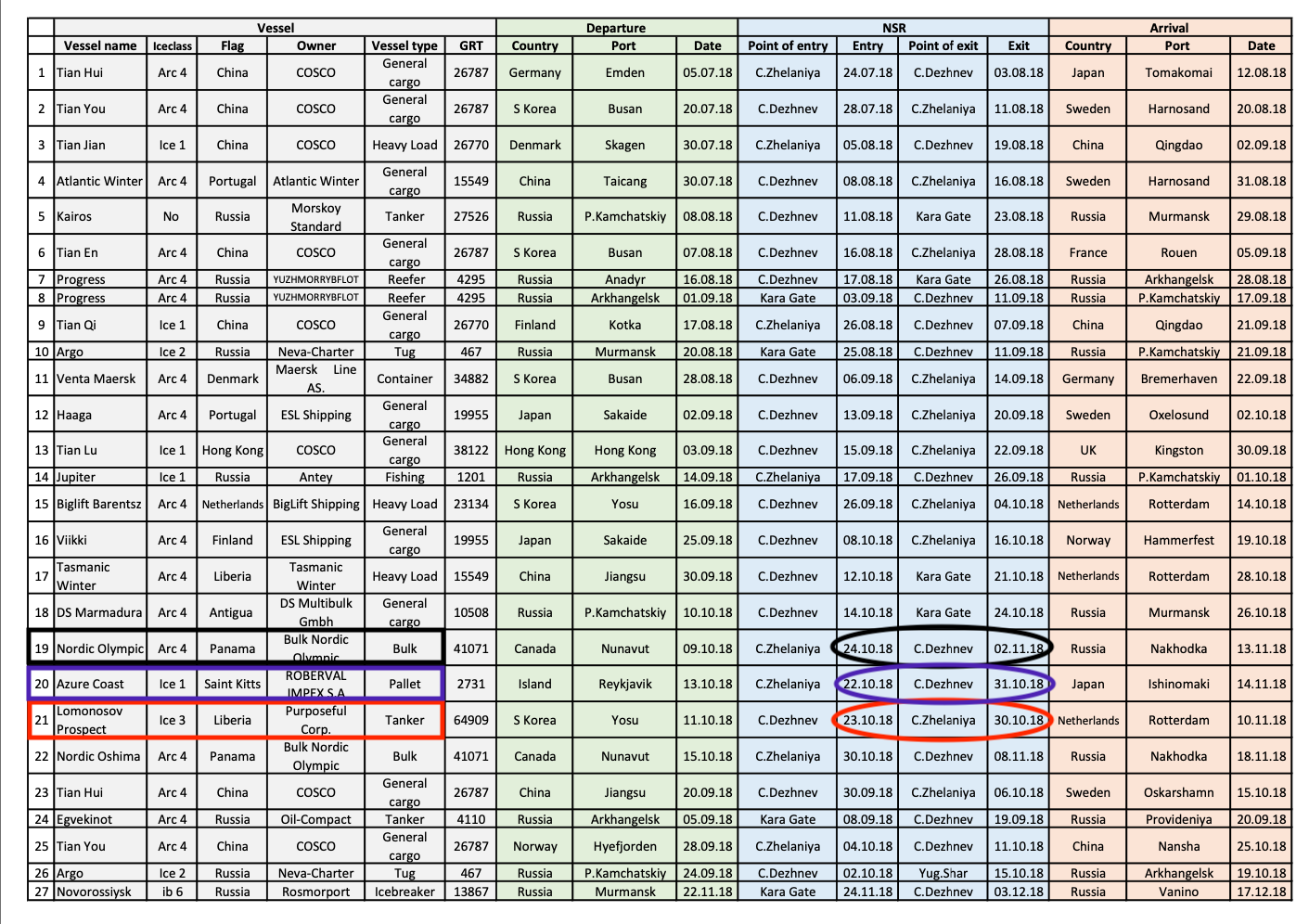

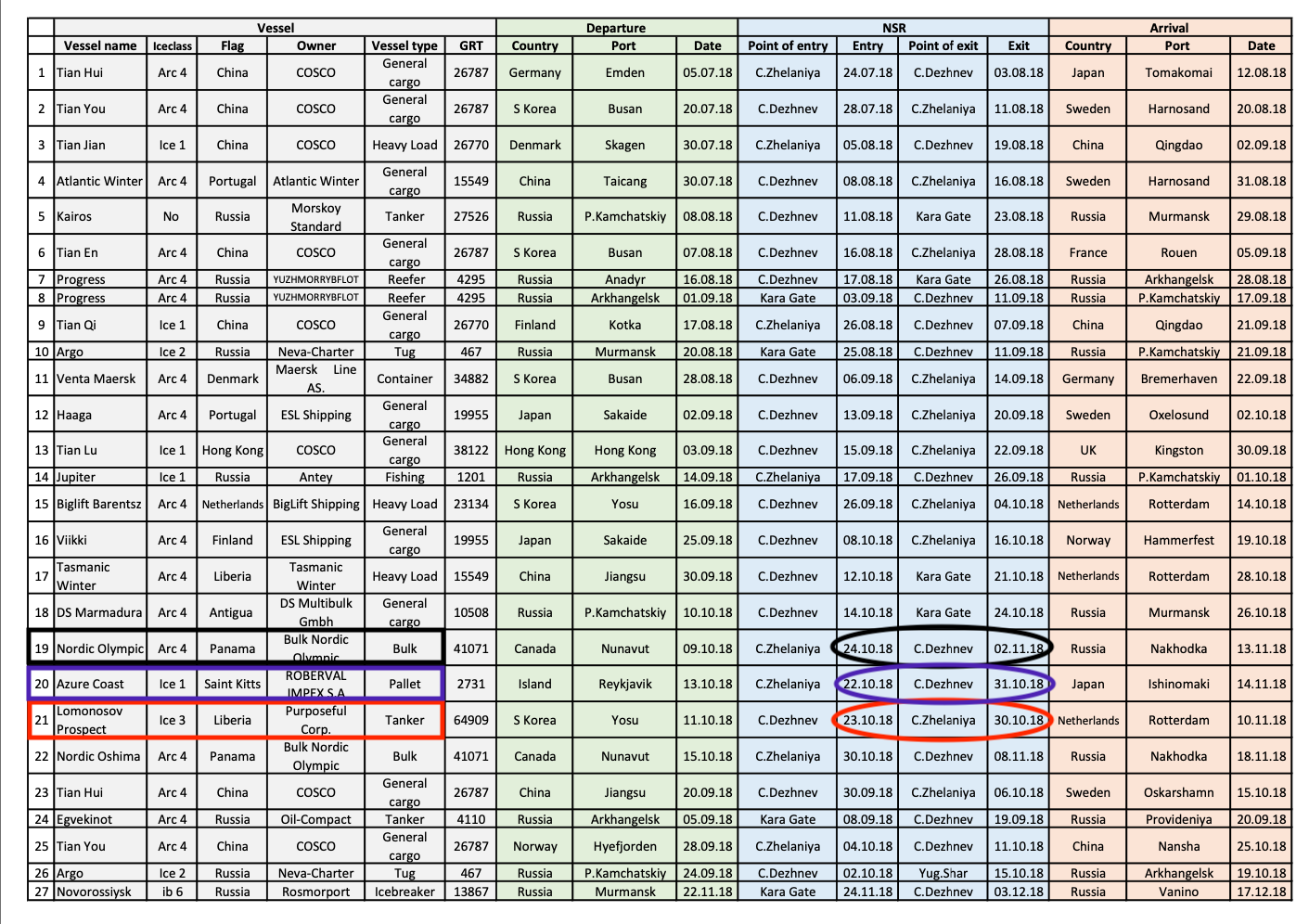

The lack of transparency is spilling into the Arctic, as from over 23 commercial vessels that transited through the NSR in 2018, 6 were from flags of convenience (Panama, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Bahamas, Liberia, Antigua and Barbuda), representing 26% of the transit.[43] While these numbers are small, scholars have predicted increased shipping via the NSR in the coming years, as Russia and China collaborate on infrastructure rebuilding.[44] See Table 2, which shows NSR shipping statistics for FOC flag states.

Table 2: Vessels that Sailed the NSR under a FOC

Four vessels are registered under the ice-class “Arc 4,” which is, according to the Russian Maritime Register of Shipping, the lowest legal ice-class for Arctic ships.[45] Moreover, one ship is a tanker registered for ice-class “Ice 3,” which is, again, according to the Russian Maritime Register of Shipping, for non-Arctic ships.[46] Such a ship, which sailed through the Northern Sea Route between October 23, 2018, and October 30, 2018, represented a significant oil-spill threat, given that it was below code and traversing the NSR at a time when sea ice begins to return. Finally, the last of the six ships are registered and approved for ice-class “Ice 1,” the lowest ice-class for non-Arctic ships, and sailed through the Northern Sea Route from October 22, 2018, and October 31, 2018, showing a significant deviation from Russian legal regulations on paper and a lack of enforcement. Such FOC shipping can present danger to the environment due to its fragility and human life, given the lack of search and rescue infrastructure. Given that there is no transparency from the FOC Flag states, how are other States, let alone NGOs and individuals, to monitor the increased shipping and risk in the near future? Overall, six of the seventeen ships were not registered and approved as Arctic ships[47].

Despite being classified as Ice-Class Arc4, vessels may follow navigation conditions depending on the service areas,[48] the conditions varying from Extreme to Easy. However, in the document “Rules for the Classification and Construction of Sea-Going Ships” of the Russian Maritime Register of Shipping,[49] the conditions are not defined per se, showing a lack of good governance, as that leaves open loopholes and lets FOCs off the hook.

Flexibility has always been at the core of maritime regulation, which is reflected in the IMO’s conventions due to the changing nature of sea conditions. One example is Rule 2 of the COLREG 72 Convention,[50] but at what point are conditions to be considered easy for a well-defined ice-class hull and what type of class is meant to handle strictly defined maximum ice conditions? These questions must be resolved before a catastrophic incident in the NSR or elsewhere in the Arctic.

The previous analysis highlights the environmental risk the FOCs represent in the Arctic. Furthermore, following a study carried out by Arctic Council’s PAME Working Group, of over 207 vessels that sailed the NSR from 2011 to 2015, 94 were tankers,[51] representing 45% of the traffic and underlining the environmental risk in terms of oil spills in the Arctic. Based upon the above research, both online and via in-person phone calls, the authors conclude FOCs are not transparent and should be held more accountable.

Future Policy Proposals

There are several future policy proposals to improve transparency and accountability among the FOC States. The first future policy proposal is to require transnational corporations to begin doing country-by-country reports. This type of reporting requires companies that engage in international production to name each country the company is operating in as well as all the subsidiaries and affiliates within said country, the performance and tax charge of each subsidiary and affiliate, details of the cost and net book value, gross and net assets of its fixed assets in each country.[52] This type of report was implemented for mineral and energy companies registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in July 2010 from the passing of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act and has been global in its reach, given the participant States in the Leading Group.[53] The reports detailed the payments remitted to countries of corporate origin (home) and countries of investment (host). This type of corporate, country-by-country reporting (CbC) creates a natural, albeit limited, sanction. Corporations eager to annul disclosure are forced to give up locations.

Similarly, the E.U. has already begun to receive CbC corporate records “to help investors to better assess the different national activities of multinational companies; and to enhance transparency about capital flows, for instance, to better enforce tax rules.”[54] This should be broadened to ensure that companies using FOCs to obfuscate dubious activity are brought to account. Implementing country-by-country reports for transnational corporations will create a transparency requirement for these companies, many of which operate shipping vessels engaged in IUU fishing. Often the FOC States do not have protections to ensure full disclosure by the owner of the ship.[55] The owner may be trying to hide this info for financial reasons, such as gaining anonymity using a tax haven. In contrast, others may be conducting illegal activities, such as illegal fishing, money laundering, and human trafficking,[56] and the owner wants not to be directly linked with those activities.

The second future policy proposal would call for upgraded Domestic Port State Controls. Port State Controls refers to “the inspection of foreign ships in national ports to verify that the condition of the ship and its equipment comply with the requirements of international regulations and that the ship is manned and operated in compliance with these rules.”[57] By upgrading those controls, ships can be held more accountable even if the flag of which it flies under is not holding it up to the same standards. One such way is to encourage the signing of the 2017 Paris Memorandum of Understanding, which creates a White, Grey, and Black List, with Ukraine joining the latter in 2019.[58] It has resulted in 3,781 detentions in 2016[59] and is slowing gaining more membership.

This can also be done in creative ways. In the United States on February 19, 1998, RCCL was indicted in Miami on a single count, not for dumping, but for “making” a false statement to the Coast Guard. The Nordic Empress discharged its waste in international waters, but the ship had presented the Coast Guard in Miami with an oil record book that omitted the discharge. While making a false statement to the Coast Guard is a crime in the United States, this was one of the first times the statute was used in this manner.[60] This is an example of upgraded Domestic Port State Controls that can help prevent illegal operations that FOC states otherwise go unchecked.

The final future policy proposal is to enhance regional/international agreements. In addition to cooperative efforts, existing conventions may be strengthened by supporting international agreements, such as MOUs. Fisheries management officials have proposed bilateral agreements between states with adjacent fishing zones or RFMOs that include mutual arrest powers. For example, Australia and France recently agreed to such a treaty, which would allow a French warship, for instance, to enter Australian waters and arrest a pirate FOC-IUU toothfish vessel and allow an Australian boat to do the same in French waters.[61] There are additional agreements regarding regulations on shipping. One such agreement is the Model Agreement on Exchange of Information put out by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Committee on Fiscal Affairs.[62] Currently, 33 countries/jurisdictions have made these commitments.[63] This means those countries/jurisdictions will begin implementing the standards laid out in the agreement of transparency and exchange of information, which include measures to ensure transparency of ownership, by allowing agreements such as the Australian and French as well as the Model Agreement on Exchange to be implemented domestically and internationally increases the ability to regulate ships in other ports and policy regarding FOC vessels.

Conclusion

The FOCs of Panama, Honduras, and Liberia are uniformly and highly non-transparent based on their adopted definition of transparency, which stands in stark contrast to the transparency of Norway. This is based on the Authors’ personal experiences with live calls and comparing access to information in different jurisdictions, it is clear that FOCs are reticent to give any information over the phone and clam up if approached by any outsider, such as Jonathan Wood’s call with Liberia in English. Thomas Viguier’s call in Spanish to Honduras resulted in disorganized information, yet led to results that one could not call “good governance,” given the pushy attitude of the Honduran representative in trying to make a sale at any cost; however, Mr. Viguier experienced silence in Spanish as well in his Panamanian call. Overall, the authors noted inaccessibility and conflicting information on all of the websites explored, particularly Honduras. The best-run website was Liberia’s, yet it was a labyrinthine experience to find a phone number to call. Even the Spanish countries as their primary language did not provide accurate information, and the translations to English were severely lacking. As to timeliness, we did not receive any calls back or responses to email, yet the authors are confident that they could have registered the Stena Nordica via Honduras. While this contribution focused primarily on transparency, this impinged on multiple levels of good governance and gave the authors a tangible sense of agreement that FOC enforcement’s, or lack thereof, of the status quo and its transparency, as earlier defined, is severely lacking.

This lack of transparency is already having an impact. Given the fact that FOCs are already using the Northern Sea Route, including oil tankers, the risk of an emergency of an oil spill from an FOC-flagged vessel in the Arctic is imminently possible. Therefore, by bringing up the various proposals from Section V, supra, within the auspices of the Arctic Council, the ad hoc meetings of the Coastal Arctic Five, or the International Maritime Organization, there can be a much-needed dialogue on preventing the disasters that have occurred in the global South through lack of transparency and enforcement from happening in the very fragile environment in the Arctic. Given Norway’s membership in all of the above fora, and their transparency in ship registration, perhaps they may play a leadership role for stewardship of Arctic shipping transparency.

Endnotes

[1] Jamie Christy, “The Almost Always Forgotten, Yet Essential Part of Our World: An Examination of the Seafarer’s Lack of Legal and Economic Protections on Flag of Convenience Ships,” 32 U.S.F. Mar. L.J. 49, 50–51 (2020).

[2] Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, “Arctic Marine Strategic Plan 2015-2025,” PAME, available at https://www.pame.is/images/03_Projects/AMSP/AMSP_2015-2025.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[3] United Nations Treaty System, “United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea,” United Nations (1982), at Art. 24, para. 1(b), available at https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[4] Lloyd’s List, “Top 10 Flag States 2018,” Lloyd’s List Maritime Intelligence, (December 10, 2018), available at https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1125024/Top-10-flag-states-2018 (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[5] See Christy, supra note 1, at pp. 49-51.

[6] See Goodman, Camille Jean, “The Regime for Flag State Responsibility in International Fisheries Law – Effective Fact, Creative Fiction, or Further Work Required?” Australia & New Zealand Mar. L.J., Vol. 23, pg. 157 (2009), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266440227_The_Regime_for_Flag_State_Responsibility_in_International_Fisheries_Law_-_Effective_Fact_Creative_Fiction_or_Further_Work_Required (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[7] Hamad, Bakar, “Flag of Convenience Practice: A Threat to Maritime Safety and Security,” IJRDO-Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research, 1:8 at pg. 218(August 2016), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308308749_Flag_of_Convenience_Practice_A_Threat_to_Maritime_Safety_and_Security.

[8] Tiili, Kristin & Ramakers, Annelien, “Rule of Law and Transparency in Modern Norwegian Whaling (2006-2015),” Nordicum-Meditteraneum 12:1 (2017) available at https://nome.unak.is/wordpress/volume-12-no-1-2017/double-blind-peer-reviewed-article/rule-law-transparency-modern-norwegian-whaling-2006-2015. (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[9] Johnstone, Rachael Lorna & Ágústsson, Hjálti Ómar, “Practicing What They Preach: Did the IMF and Iceland Exercise Good Governance in Their Relations 2008-2011?” Nordicum-Meditteraneum 8:1 (2013) available at https://nome.unak.is/wordpress/08-1/c48-article/practicing-what-they-preach-did-the-imf-and-iceland-exercise-good-governance-in-their-relations-2008-2011/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020) (emphasis in original).

[10] Friedl Weiss & Assisted by Silke Steiner, “Transparency As an Element of Good Governance in the Practice of the EU and the WTO: Overview and Comparison,” 30 Fordham Int’l L.J. 1545, 1549 (2007).

[11] Ford, Jessica & Chris Wilcox, “Shedding Light on the Dark Side of Maritime Trade—A New Approach for Identifying Countries as Flags of Convenience,” Marine Policy, pg. 298, (January 2019).

[12] See Morris, R., & T. Kilkauer, “Crews of Convenience from the Southwest Pacific,” New Zealand Journal of Industrial Relations, 26(2), (2001) at pg. 188.

[13] See Broeze F., The Globalisation of the Ocean: Containerisation from the 1950s to the Present, (St. John’s Newfoundland: International Maritime Economic Historic Association) (2002).

[14] Urbina, Ian, “Stowaways and Crimes Aboard a Scofflaw Ship,” N.Y. Times (July 19, 2015), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/19/world/stowaway-crime-scofflaw-ship.html (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[15] Kshetri, Nir, “Marshall Islands,” The Statesman’s Yearbook (Jan. 4. 2020) at pp. 813-815.

[16] See Clark, Andrew, “BP Oil Rig Registration Raised in Congress Over Safety Concerns,” The Guardian, (May 30, 2010), available at https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/may/30/oil-spill-deepwater-horizon-marshall-islands (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[17] See Sharife, Khadija, “Flying a Questionable Flag: Liberia’s Lucrative Shipping Industry,” Reportage World Policy Journal, (Winter 2010/2011) at pg. 113, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/40963779.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Af0254f5d81676f199b2878706f9454f9 (last accessed August 25, 2020).

[18] Goodman, note 9 supra, at pg. 164.

[19] The authors may be contacted to provide any more details on the ship, as necessary, to prove their knowledge of this vessel.

[20] See UNCLOS, note 3 supra at Arts. 26, 53.

[21] Norwegian Maritime Authority Website, “Registration of Ship in the NIS,” Sjøfartsdirektoratet, available at https://www.sdir.no/en/shipping/registration-of-commercial-vessels-in-nisnor/new-registration-nis/documentation-requirements-nis/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[22] Norwegian Maritime Authority Website, “Organizational Structure and Employees,” Sjøfartsdirektoratet, available at https://www.sdir.no/en/organization/organizational-structure-and-employees/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[23] See Norwegian Maritime Authority Website at “Recognized Organizations,” supra note 17, available at https://www.sdir.no/en/shipping/vessels/vessel-surveys/approved-classification-societies/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020.)

[24] See id. at “21-December-2009-No.-1738-Tariff-of-Fees,” supra note 17, available at https://www.sdir.no/contentassets/e7ee839cecce49cb8286b5fba381c841/21-december-2009-no.-1738-tariff-of-fees.pdf?t=1582119505790. (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[25] See id. at “Trade Areas NIS Ships,” supra note 18, available at https://www.sdir.no/en/shipping/registration-of-commercial-vessels-in-nisnor/new-registration-nis/trade-areas-nis-ships/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[26] See id. at “New Registration in the Shipbuilding Register,” supra note 17, available at https://www.sdir.no/en/shipping/registration-of-commercial-vessels-in-nisnor/new-registration-the-shipbuilding-register/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[27] See id. at “New Registration in the Shipbuilding Register,” supra note 17 available at https://www.sdir.no/en/shipping/registration-of-commercial-vessels-in-nisnor/new-registration-the-shipbuilding-register/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[28] See Johnstone & Ágústsson, supra, note 11.

[29] Autoridad Maritima de Panama, “Servicio Exterior,” Republica de Panama, available at https://amp.gob.pa/servicios/marina-mercante/abanderamiento-de-naves/servicio-exterior/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[30] All phone call logs were conducted using Jonathan Wood’s phone and logs are available to review upon request.

[31] Dirección General de la Marina Mercante Honduras Website, “Directorio de Contactos,” Dirección General de la Marina Mercante Honduras, available at https://marinamercante.gob.hn/?page_id=2336 (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[32] Author Jonathan Wood, currently working as an attorney in private practice, can provide insight into the legal market and provide more details, if necessary, as to how out of line that price is with the market.

[33] See note 27 supra.

[34] See id. at “IAIP,” supra note 27, available at https://portalunico.iaip.gob.hn/portal/index.php?portal=343&Itemid=59 (Last accessed April 18, 2020).

[35] See Facebook, “Community Standards,” Facebook, available at https://www.facebook.com/communitystandards/ (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[36] See “Registro de Buques,” supra note 24, available at http://marinamercante.gob.hn/?page_id=2342 (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[37] Information on this individual can be provided privately as the authors found him on LinkedIn but for purposes of this paper, we choose to preserve his anonymity.

[38] Marine Traffic Website, “STENA NORDICA (Ro-Ro/Passenger Ship) Registered in Bahamas,” MarineTraffic, which includes Vessel Details, Current Position and Voyage Information (IMO 9215505, MMSI 311000843, Call Sign C6EB2), available at https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:194642/mmsi:311000843/imo:9215505/vessel:STENA NORDICA (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[39] See Dirección General de la Marina Mercante Honduras, “Ver Documento 7,” La Gaceta, (May 24, 2018), available at https://portalunico.iaip.gob.hn/portal/ver_documento.php?uid=MzkyMjU4ODkzNDc2MzQ4NzEyNDYxOTg3MjM0Mg== (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[40] Furthermore, seeking more information was difficult as the office itself did not know where all of the information was located as while Mr. Viguier was on hold, the initial person on the phone did not place him on hold. He heard shouting from the individual who picked up the phone, asking where certain offices were physically located and who was supposed to handle the topic of international ship registration. An entire discussion, held in Spanish, over the phone about whom to transfer him to before the individual realized his mistake and placed Mr. Viguier on hold. Therefore, Honduran transparency was shockingly low.

[41] See Liberian Registry, “Contacts,” Liberian Registry, available at https://www.liscr.com/liberian-registry#new-york (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[42] See Liberian Registry, “All Flags Are Not Alike,” YouTube (June 28, 2018), available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AKY3pp6wtUA (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[43] Arctic-LIO, “Transits 2018,” Northern Sea Route Information, available at https://arctic-lio.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Transits_2018.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[44] See generally Tom Røseth, “Russia’s China Policy in the Arctic, Strategic Analysis,” Taylor & Francis, 38:6, pp. 841-859, available at DOI: 10.1080/09700161.2014.952942 (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[45] See Russian Maritime Register of Ships, “Rules for the Classification and Construction of Sea-Going Ships,” Government of the Russian Federation, at pp. 12–13, (September 9, 2016), available at https://rs-class.org/upload/iblock/ee4/ee42f902bc2f1b2eb2bbeff75efffcee.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[46] See id. at pg. 12.

[47] Approved ships included an icebreaker, a harbor tug, a fishing vessel, a bunkering vessel engaged in harbor activity and 2 cargo vessels engaged in short-term cabotage.

[48] See id. at pg. 13.

[49] See id.

[50] United Nations Treaty Series, “Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea,” United Nations (1972), available at https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201050/volume-1050-I-15824-English.pdf> (Last accessed August 25 2020).

[51] Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment, “Types of Ships 2011-2015,” PAME (no date given), available at https://www.pame.is/images/03_Projects/AMSA/NSR/types-of-ships_2011-2015.jpg (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[52] See Richard Murphy, “Country-by-Country Reporting: Holding Multinational Corporations to Account Wherever They Are,” Task Force for Financial Integrity & Economic Development, (June 2009), available at http://www.financialtransparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Final_CbyC_Report_Published.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[53] See id. at pg. 2.

[54] European Commission “Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment assessing the potential for further transparency on income tax information Accompanying the document Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of income tax information by certain undertakings and branches,” European Commission, SWD/2016/0117 final – 2016/0107 (COD), (April 12, 2016), available at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52016SC0117

(Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[55] See Hamad, Bakar, “Flag of Convenience Practice: A Threat to Maritime Safety and Security,” IJRDO-Jounral of Social Science and Humanities Research, 1:8 at Abstract, (August 2016), available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308308749_Flag_of_Convenience_Practice_A_Threat_to_Maritime_Safety_and_Security (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[56] See Sharife, Khadija, “Flying a Questionable Flag: Liberia’s Lucrative Shipping Industry,” Reportage World Policy Journal, (Winter 2010/2011) at pg. 115, available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/40963779.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Af0254f5d81676f199b2878706f9454f9 (last accessed August 25, 2020).

[57] Anonymous, “Port State Control,” International Maritme Organization, available at http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/MSAS/Pages/PortStateControl.aspx (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[58] See Press Release, “Safeguarding Responsible and Sustainable Shipping,” Paris Memorandum of Understanding, at Executive Summary (2017), available at https://www.parismou.org/2017-paris-mou-annual-report-%E2%80%9Csafeguarding-responsible-and-sustainable-shipping%E2%80%9D (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[59] See id.

[60] See United States v. Royal Caribbean Cruises, Ltd., 11 F. Supp. 2d 1358, 1365 (S.D. Fla. 1998) (holding “Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS), as an allegedly more specific ‘false statements’ law regulating cruise ship’s conduct in failing to properly report alleged discharge of oil, did not preclude prosecution under the False Statements Act for false statements allegedly made to Coast Guard upon ship’s arrival in United States port.”)

[61] Australia Country Fact Sheet, “Treaty Between the Government of Australia and the Government of the French Republic on Cooperation in the Maritime Areas Adjacent to the French Southern and Antarctic Territories (TAAF), Heard Islands and the McDonald Islands,” Government of Australia, (Canberra, 24 November 2003), available at www.aphref.aph.gov.au_house_committee_jsct_12may2004_treaties_frnia.pdf (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[62] See Maritime Transport Committee, “Maritime Security—Ownership and Control of Ships: Options to Improve Transparency,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, (December 17, 2003), available at http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DSTI/DOT/MTC(2003)61/REV1&docLanguage=En (Last accessed August 25, 2020).

[63] See id. at pg. 22.