- Introduction

The Oura Archipelago is a biocultural landscape in the northern Baltic Sea, off the west coast of Finland. I call the Oura Archipelago ‘The Shining Islands’ because of the way the sun sets behind the islands in August. It creates a special glow. (- Field notes of the author, August 2021)

Oura used to be the hub of small-scale commercial coastal fisheries in Finland (Mellanoura et al. 2023). The archipelago can be considered a biocultural landscape – a nexus of human-nature activity with considerable depth and spatial relevance (Elands et al. 2019). This article explores how the relationship between political, economic and social factors (Alexander et al. 2022) have contributed to creating internal and external interpretations of the archipelago. Internal perspectives (Mosby et al. 2025) of the Archipelago as a landscape stem from the fishing community or Oura itself. Whilst interpretations of the archipelago as an external demarcation stem from actors such as Finnish state authorities and the European Union (Loring 2017, Campling and Colás 2021). More specifically we situate the Oura Archipelago in the nexus of conservation, traditional culture and geography, with elements of political ecology (Alexander et al. 2022). Our research question concerns the quality of the interface between a small marine community (Mosby et al. 2025) and external governance. We investigate this through brief, relevant case studies from Oura – the practices of drift netting, seal hunting and, finally, the arrival of marine conservation. We also refer briefly to Clover (2022) to consider the potential of marine restoration and rewilding as a solution.

Several key references exist concerning matters of marine equity (Alexander et al. 2022, Mosby et al. 2025), but very few from the Oura Islands, most of them in Finnish. We wish to correct this by offering a first international reading of Oura, in English, focusing on key topical issues as well as analysis by Campling and Colás (2021). We draw on Campling and Colás (2021) to explore the links between the sea, capitalism and wider economics in the unique case of a cryosphere-situated northern Baltic archipelago. Their analysis of the link between capitalism – understood as a historic and ongoing economic process – and the oceans is a deep reading of the Seas. According to these authors (2021) the oceans have periodically acted as sites and sources of competitive innovation and experimentation in finance, technology, insurance, labour regimes and spatial governance. Additionally, they posit that capitalism can be seen to have developed in its approach to the major geophysical hurdle of the appropriation of nature through the enclosure and commodification of the sea. They summarize a large volume of analytical thinking regarding the seas. Here we argue that Oura, a biocultural landscape in the Baltic, provides some exceptions to their reading (2021). Campling and Colás (2021) refer to these small-scale and traditional fishing societies as being vulnerable to capitalist processes in which the sea is seen as a domain of innovation and the stimulation of growth and gain. Our enquiry has two central components related to biocultural existence in the Oura Archipelago (Elands et al. 2019).

First the article explores the dynamics – social and economic and, ultimately, ecological – of small-scale drift netting – rääkipyynti. Second, it considers the changing role of Baltic seals and seal hunting (Sellheim 2018) in the archipelago. In both cases we consider the realities of different eras and the interface between internal and external pressures and governance processes. Our third level of analysis concerns the formal protection of the Archipelago as part of a National Park and the impacts of this designation on the internal landscapes of Oura. These case studies are assessed and positioned in the analytical frame of how ‘terraqueous predicaments’ (interplays between water and terrestrial systems) (Campling and Colás 2021: 3) and sea-linked economic processes play out in Oura.

Loring (2017) argues in his research regarding the Alaskan fisheries that ethical considerations can be inseparable from the ecological aspects of managing fisheries. According to him, when communities grapple with the sustainability of fisheries, they are simultaneously seeking to define the socially acceptable uses of those resources. This political ecological approach is also relevant in the case of the Oura Archipelago. It forms a central theoretical part of this work, in addition to the contributions of Campling and Colás (2021).

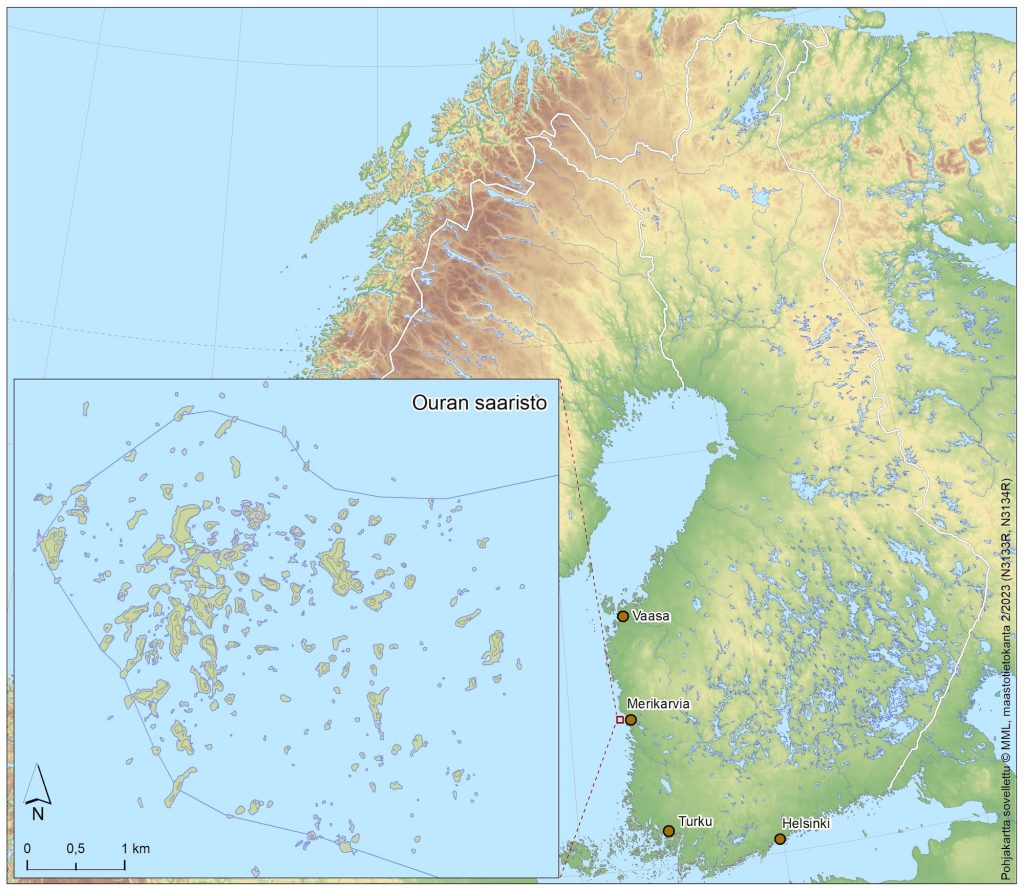

The Oura Archipelago is of national relevance in matters of culture and nature in Finland. The Bothnian Sea National Park, totaling 940 square kilometers, was established to protect this unique heritage in 2011 (Metsähallitus 2022). This designation means that the Archipelago’s fishers have rights to continue harvesting inside the Park. Oura is subject to post-glacial uplift, meaning that new islands continue to appear as the land ‘bounces back’ after the last ice age. Sea buckthorn berry patches are a feature of the outer island. Northern birds including the Arctic tern call Oura ‘home’. The European Union designated Oura as a Natura 2000 Protected Area in the 1990s. Marine protection constitutes, in Campling and Colás’ (2021) analysis, more as representations of space to be dialectically intertwined with the moments of experimentation and innovation, in extension of the maritime commodity frontier, i.e. ordering the ‘natural spaces’ into human realms.

Figure 1. Map of the Oura Archipelago on the west coast of Finland and nationally

The oldest human settlements in the Oura Archipelago are stone dwellings used as seasonal fishing huts and shelters. Some date from pre-historic times. Seal hunting, both for the Baltic ringed seal (Pusa hispida) and the Grey seal (Halichoerus grypus), as well as fishing, were central to the lifeways of early Oura communities. We can say that these local Finnish communities developed the earliest ‘traditional’ lifeways in the area (Campling and Colás 2021), and that these lifeways were and are incompatible with modern capitalism. According to Campling and Colás (2021) nautical traditional cultures saw oceans as a crucial life force having cosmic power. This was certainly true in Oura.

Later, in the 1900s, seal hunting in Oura focused on the Grey seal. Sometime in the 1800s, innovative Oura fishers adopted drift netting for whitefish and Baltic herring from Åland (originally from Gotland, Sweden). By combining this technique with an innovative boat style, rääkipaatti, they developed a new and successful way of fishing that provided wealth for families in the archipelago (Mellanoura et al. 2023). Campling and Colás (2021: 183) refer explicitly to “commodity frontiers” like Oura, which they position as historical zones of innovation and evolving fishing gear. The proliferation of rääkipaatti vessels and drift netting from other parts of the North Baltic can be seen in this frame. They represent an example of a commodity frontier where technological innovations (in this case dating from the 1800s) and local adaptations enabled people to access new areas of the sea and exploit new temporal windows.

Longlining for salmon, fish traps for Baltic herring and whitefish, seining and under-ice gill netting for burbot are some of the other commercial fishing techniques that were employed in the Archipelago until the 1990s. Catches were sold on shore to the city of Pori and beyond. For a portion of the 1900s the municipality of Merikarvia was Western Finlands premiere fishing hub. As well as providing food, income and identity, Oura’s fishery was a source of wider societal equity for the women and men of the archipelago. It was often families who did not own much, or any, land who became fishers on the open sea, to which they did have access. In Oura, the abundance of marine resources and fishers’ ingenuity meant that these families could support themselves and their relatives through fishing alone, without the need of farmland or use of forests (Mellanoura et al. 2023).

Campling and Colás (2021: 61) describe the origins of this type of situation with reference to processes of Enclosure in the UK: “In the UK peasants and other direct producers were dispossessed from their access to communal lands and customary rights and compelled into the double freedom of a capitalist market – relieved from their means of subsistence and at liberty to exchange their labour power for wage.”

Finland’s grand allotment proceedings, which transformed communally held areas of land and sea into private property, acted as a liberating window for the fisher people of Oura. In this sense Oura’s local adaptations to a historic change/opportunity deviate from the larger process described in Campling and Colás’ (2021) analysis. Land ownership led the outer archipelago to become a theater for small-scale, landless fishers to innovate, take substantial harvests and develop a coastal way of life that was more strongly related to the traditional uses of the sea than a profit-driven market system (Mustonen 2014).

Oura and neighbouring Pori were once known as nodes of innovative coastal fishing techniques (Campling and Colás 2021). Into Sandberg, a fisher from Mäntyluoto in Pori wrote down his traditional knowledge, which later appeared in the highly influential book Kalastaja ilman merta / Fisherman without a Sea (Saiha and Virkkunen 1986). Sandberg was amongst the first to document the environmental impacts of industrial development on west coast fish populations. His testimony provides an excellent example of what Campling and Colás (2021: 171) call a process where the “commodification of marine life contributed to the destruction of Indigenous food ways.”

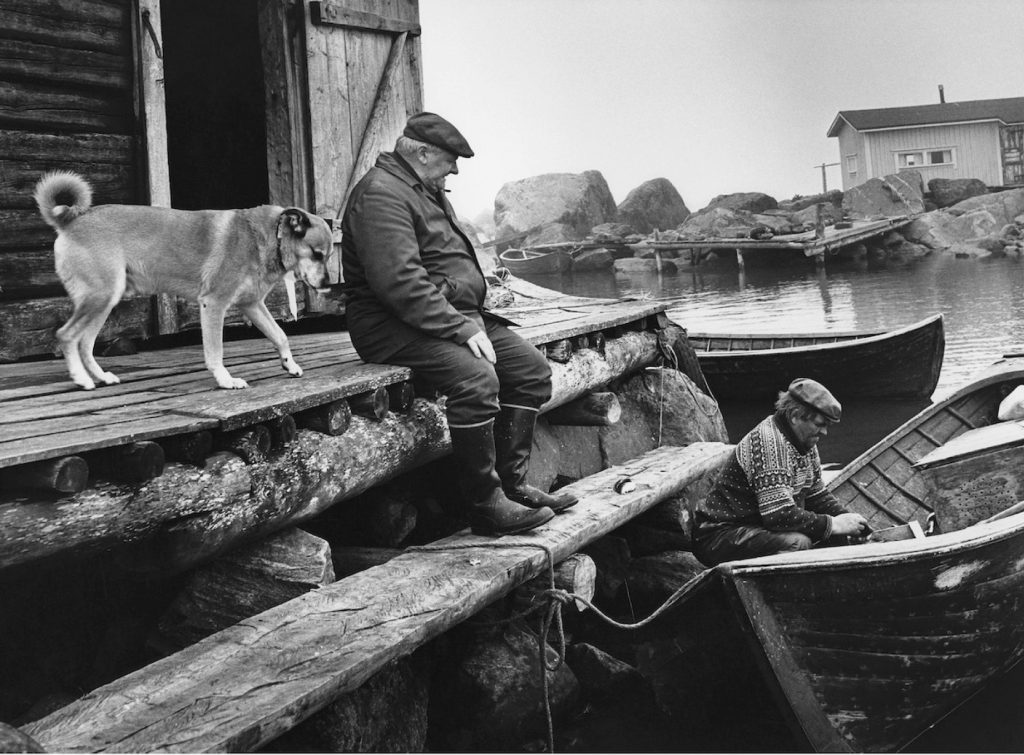

Figure 2. Famous fisherman Eero Veneranta (right) on the Kaddi Island with a colleague. Photo: Matti Pitkänen, used with permission.

Sandberg observed Baltic Herring losing eyes to pollution, declines in the breeding success of Grey seals due to contamination of the food chain in the late 1960s, and early baseline observations of climate change in the 1970s. These observations are on a par with the work of Inuit from Canada (Alexander et al. 2022) and reinforce their observations of the disturbing ways our seas are changing. Fishers from Oura, like Sandberg, (Saiha and Virkkunen 1986) knew their seas intimately and were alert enough to speak out when they saw that the whole system was in trouble. The free gift of marine life (Campling and Colás 2021) met with industrial land capitalism and paid the price.

The fishers and hunters of Oura lived in boreal northern sea and icescapes in ways that were almost completely waste-free (Mellanoura et al. 2023). The boats were made from wood. Before the advent of nylon (circa. 1940s), nets were made at home from local natural materials. No part of the seal or fish was wasted (Saiha and Virkkunen 1986). All things held importance. The seasonal cycle began in late-July with drift netting, followed by fishing for salmon and whitefish during the big storms of the autumn. Early ice fisheries in December were followed by the spawning of burbot, spring seal hunts on the ice and salmon fish trapping during the burst of northern spring light in April-May. This was the foundation of the rather autonomous, independent world and biocultural landscape of Oura (Mellanoura et al. 2023 and what Campling and Colás (2021) refer to as traditional sea cultures).

The people of the Oura Archipelago lived with their islands, sea and animals in a communion which is very hard to summarize and risks conveying a romanticized view (Saiha and Virkkunen 1986). The following can be said, however: from the early 1800s to the 1940s, Oura was a largely self-contained biocultural community (Elands et al. 2019) that maintained mostly good relations with the sea. By the 1990s new regulations for protection of fish species and marine mammals spelled the end of the drift net fishery and altered seal hunt capacity. In the 2010s the area was designated as a National Park (Metsähallitus 2022). This process is similar to that described by Campling and Colás (2021). They note that these incursions of external governance can be seen as markers in a process transforming ocean biomass into new forms of commodity capital. This process alters the nature and organization of Earth’s biocultural metabolism in ways that bring biological and commercial rhythms into conflict. In other words: the ordering of marine space in Oura was modernized.

- Materials and Methods

This article focuses on two landscape practices – drift netting and the seal hunt (Sellheim 2018). The analytical timeframe considered is 1850 to 2010, the year in which the Bothnian Sea National Park was established (Metsähallitus 2022). We use a compilation of oral histories the authors have collected during fieldwork in Oura, which began in the 1970s. The materials are summarized in Mellanoura et al. (2023). These locally-collected materials constitute biocultural elements of life in Oura. We also draw on Campling and Colás (2021) to identify interfaces between traditional Finnish marine fishing culture and the relations it maintains with the ocean, and land-born capitalism. We pay particular attention to the processes by which the ocean receives pollution, and impacts and transformations whose origins are far removed from the community level but nonetheless have major local effects. The changing context of drift netting and seal hunting are also reflective of the political ecology of a given era (Loring 2017). For these analytical systems of practice this change is explored. Political ecology in our context refers to the policies and societal facts of the environment across time.

Central to the political ecology of the Oura Archiplago over the past 160 years is what Huntington et al. (2017) calls ‘autonomous response space’. The marine coastal environment and biocultural landscape of Oura has never been isolated even though – as an archipelago – it lies at the margins of society (Loring 2017). Both drift netting and the seal hunt (Sellheim 2018, Geust 2021) have been affected by major changes in the period of study presented here. These changes include loss of fish stocks and resources due to pollution, emergent nature conservation, damming of spawning rivers flowing into the Baltic, and rural depopulation of the Oura and other archipelagoes. Local fishing communities, families and individuals have responded to the shifting political, economic and social factors related to the seal hunt and fishery in several different ways (Loring 2017, Campling and Colás (2021). This suite of responses incudes economic and social innovations such as the adoption of drift nets in Oura in the 1800s. In relation to the marine resource this change points to the roles of commodity frontiers as areas of innovation (Campling and Colás 2021).

Our analytical view will be described through the assessment of community materials, local literature and oral histories that have recently been summarized in Mellanoura et al. (2023). This constitutes a large collection of traditional knowledge, ecology and history from Oura. Additionally, official documents from the Bothnian Sea National Park (Metsähallitus 2022) and EU Natura 2000 are analyzed as secondary materials offering insights into the history of political and ecological change in Oura from an external perspective. A closer look at the case studies enables us to understand Oura as an interconnected seascape where two rivers, Kokemäenjoki (one of the so-called (main) national rivers of Finland) and Merikarvianjoki, flow out to sea. This connects the rivers and the archipelago into a dynamic brackish water seascape where evolution is still ongoing (e.g. marine species adapting to freshwater habitats). A very productive biological habitat where whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) and Baltic herring (Clupea harengus membras) in particular have thrived. Other important fishery species include Atlantic salmon, grayling and burbot.

The large outer sea shoals of Baltic Herring and their spawning areas have given rise to a unique biocultural landscape: that of the coastal Finnish community of Merikarvia (Pecl et al. 2023). In this biocultural system seal hunting was also very prominent, with the earliest archaeological findings suggesting such hunting originating from circa 1700 BC (Broadbent 2010, Sellheim 2018).

2.1 Rääkipyynti, Drift Netting Culture of Oura

Rääkipyynti is the local Finnish dialect word for the practice of artisanal drift netting, which came to Oura from Gotland, Sweden, sometime in the latter part of the 1800s (Mellanoura et al. 2023). This technological innovation was deeply connected to the use of a certain type of a boat (Campling and Colás 2021) which, combined with the use of drift nets, enabled the efficient harvesting of Baltic herring. Drift netting involves floating a gill net in the open sea between buoys, floats and a vessel, without anchoring the net to the sea floor. In Oura, this type of fishing was often practiced at night on the open sea. Baltic herring was the original target of this form of fishing, but in later years whitefish was also caught on the open sea by Oura fisherpeople using drift netting techniques. This technology and fishing practice practice mustbe understood in its full socio-economic context (Loring 2017, Campling and Colás 2021). In Oura, this fishing innovation enabled the people of the Archipelago to muster significant incomes from the sea on their own terms at a time when their access to land, subsistence and self-governance away from the open sea was significantly limited.

Rights to fishing waters closer to mainland were tied to land ownership[i]. By contrast outer waters – i.e. the open sea that was suitable for drift netting – was available to all as a commons where the landless and poorer fishers could operate. In an interesting contrast to Campling and Colás’ (2021) analysis, the stark realities of Finnish rural land ownership enabled the outer Oura Archipelago to become a theater in which small-scale, landless fishers could preserve their autonomous response space (Huntington et al. 2017), in the sense that they were able to navigate issues from their own specific position, on their own terms.

In the heyday of the rääkipyynti (drift netting)- millions of kilograms of Baltic Herring were caught by the fishers and sold in Merikarvia, the closest harbour, and also in Pori, one of Finland’s main west coast ports. In the busiest seasons, over 300 people operated as rääkäri, drift net fishers, in the community. By the 2000s the number of local fishers practicing this form of harvest was down to 10-20 individuals (Mellanoura et al. 2023). Positioning the emergence of this fishery into the analytical frame set up by Campling and Colás (2021), we can say that during the 1800s and 1900s the autonomous existence of the Oura fishers enabled them to become a major market force without the assets usually associated with the terraqueous predicament, rather than because of them. That is, the landless status of the fishers which should have placed them at a disadvantage helped preserve their autonomous position and thereby their ability to innovate and become a major market force.

Building on their pre-existing traditional, autonomous skills and means of production and adapting some new innovations, such as the rääkipaatti vessel, the fishers of Oura self-regulated their relations with the Baltic fishing market. The difficult and complex navigational context of the Oura Archipelago, which is made up of hundreds of islets, islands and other sea features, favoured those with traditional knowledge, appropriate technologies, such as small gear, and seasonal settlements on remote islands, over any attempts to utilize larger vessels and gear to take larger harvests. This dialogue between archipelagic topography and traditional knowledge was at the center of effective self-regulation (Campling and Colás 2021). Oura’s fishers had the capacity, knowledge and inclination to order the temporal and spatial scales of their harvests, rather than attempting to maximize profits from their fishery, as would have been the case in many other parts of the world’s oceans at the time. In addition to these factors, the long annual period of polar sea ice cover acted as a limiting factor in the North Baltic, forcing fishers to adjust their lifeways and technologies.

In 2009 the European Union banned all drift netting in the Baltic, in-line with the blanket regulation of similar nets in the Mediterranean to reduce by-catch of dolphin and other non-target species. In a classic example of what Campling and Colás (2021) describe as the appropriation of marine resources, in this case through their nominal protection, a local innovative practice fell victim to a systemic approach. The EU’s decision to ban drift netting was made to protect dolphins in the Mediterranean and, in part, the vulnerable Baltic harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). The drift netting practices of Oura fishers became ‘collateral damage’ in the process of enforcing this new regulation. The Baltic harbour porpoise lives mostly in the southern Baltic, close to Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Poland. It is an extremely rare visitor to the Oura area – seen perhaps once every twenty years. The EU’s union-wide ban on drift netting gear is an example of a distant management imposition. The threat drift netting poses to Mediterranean marine animals is not a matter of dispute, but the EU’s approach to establishing new protections ignored the vastly differing local realities of fishing communities across the European continent and their contributions to negotiations. Again, this falls in line with what Campling and Colás (2021: 181) call the “Nature rights school of property”. This recognizes inequality but contrasts alternatives with an absence of property rights that, in a capitalist society, is believed to cause immediate species declines.

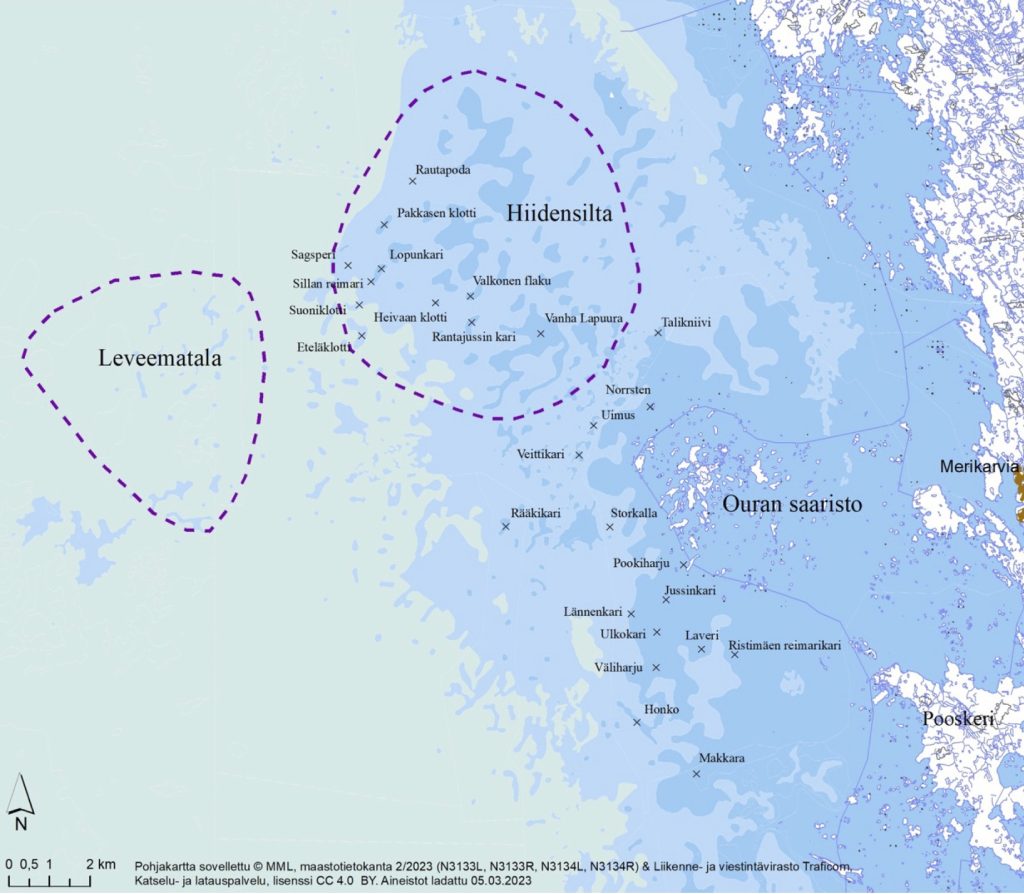

Figure 3. Shoals of the Open Sea Close to Oura.

2.2 Seal Hunt in the Northern Ice Scapes

The west coast of Finland has been the home of a seal hunt practiced by the Sámi Indigenous people since pre-historic times (Broadbent 2010). Later, non-Indigenous Finnish and Swedish communities continued this practice. From the 1700s, the most important economic activities on the coast were seal hunting and fishing (Mellaoura et al. 2023). Agriculture, at that time, was small-scale and met only subsistence needs. This reality continued, in large part, until the mid-20th Century. Around the 1970s, the rules of trading changed, and the shipping and navigation industries expanded with the advent of motorized boats and ships. Cabins, especially those in the outer archipelago, that were used by fishers and hunters to organise and provision season-specific harvest, started to lose their significance as integral parts of a wider system of seasonal movement.

Signs of ancient seal hunting and fishing traditions can clearly be seen across the entire Oura Archipelago (Sandström 2006). They are markers of what Campling and Colás (2021) refer to as traditional maritime cultures who saw the oceans as a crucial life force and cosmic power. The seal was an important and valuable catch. Seal blubber oil was sold or used by the hunters. Meat and entrails were eaten, blood was used in cooking and the skin was used to make various goods. Seal hunting required great skill, which was passed from one generation to the next, from prehistoric times (Geust 2021, Sundfeldt and Johnson 1964, Sandström 2006).

In Oura, the traditional seal hunt persisted until 1951. Sundfelt and Johnson (1964) provide us with an authentic description of the long seal hunting trips on the sea ice. These journeys usually took place in late-spring between March and May.

Sundfelt and Johnson worked with tradition holders, such as Erik Granlund, a sealing captain from further up the coast, travelling with them on the ice as a part of the traditional seal hunt. In 1964, they published the classic book Färdmän från Isarna (Seal Hunters from the Islands). Several academic and ethnographic studies regarding the seal hunt in the northern Baltic Sea have been published. However, most of these studies present an analytical framing from the researcher’s perspective, not from that of knowledge holders like Granlund (see also in Sandström 2006).

Sundfelt and Johnson (1964) documented the seal hunt of the Bergö in the northern Baltic and other island hunters as a part of the seasonal round undertaken by these coastal communities. The seal hunters’ local-traditional knowledge of the animals, sea ice, navigation, sea currents, winds, birds, weather prediction and hunting techniques is on a par with the very sophisticated seal hunting traditions of the Suursaari Baltic Finnish seal hunters.

One of the most profound messages Sundfelt and Johnson (1964) were able to convey from the hunts they participated in with Erik Granlund and his teams was the sense of freedom inherent in the seal hunt. Life on the ice, and the knowledge embedded in living that life , contained what scholars have since defined as ‘endemic values’ (Mustonen 2014). These are understood as place-based morals, ethics and ways of being that can only exist and be maintained through traditional dwelling-presence and relationships with a particular place and its citizens, in this case the sea, ice, seals and weather of the Oura Archipelago.

In Oura we know about the emergence of the first specific seal hunting guns in the 1600s (Mellanoura et al. 2023). Mellanoura et al. (2023) states that in the period from the 1600s to the end of the 1800s the seals (Ringed seal and Gray seal) were considered sacred and culturally important animals. The fat of the seal was used as oil, but the price dropped in the 1800s. This led to the hunt being maintained only by outer archipelago fishers. They used so-called seal nets made from linen which were deployed during their long hunting trips. Mellanoura et al. (2023) report that, much like other seal hunting regions of the north Baltic, the hunters had a system of taboos, ceremonies and practices for maintaining good relations with the seals during this period.

The last hunt we know of, from what we might call ‘traditional times’, in Oura, happened in 1951. The last bowl of seal soup to be prepared in Oura was served and eaten in 1968 (Mellanoura et al. 2023). After that, the build up of environmental toxins and new state regulations ended the hunt. Again, traditional maritime societies fell victim to the production and presence of, and state responses to, capitalist – imperialist – pollution, as described by Campling and Colás (2021), despite having played no part in the generation of, for example, industrial pollution. Eventually an altered seal hunt was re-started in the 2000s, with a far smaller capacity.

- Results

How did a range of political, economic and social factors shape and alter the shifting biocultural realities of the Oura Archipelago between 1850-2010? We can answer this question through the exploration of temporal shifts in the drift net fishery and in the seal hunt (Loring 2017) and by highlighting links to the emergence and development of global capitalism (Campling and Colás 2021).

Mellanoura et al. (2023) demonstrate, through maps, oral histories and written sources, that the Oura Archipelago biocultural landscape evolved, was made and re-made through the practices of a dynamic small-scale fishery and culture of seal hunting that has its roots in pre-history. Campling and Colás (2021) identify these small-scale and traditional fishing societies as being vulnerable to the capitalist process whereby the sea is seen as a domain of innovation and therefore stimulation of growth for gain.

Baltic Herring usually form spawning shoals that gather on shallow, vegetated habitats, such as underwater meadows with perennial algae and stony substrates like gravel and small stones. These form traditional, consistent spawning areas. These areas provide a special example of the special relationship between the archipelago’s communities and their biocultural landscape. Each one of these spawning areas has a name, a toponym, that contains traditional information, as well as being associated with and/or the origin point of several oral histories attached. As such, each spawning shoal’s specific habitat is woven into a ‘memory-scape’ that was held, reproduced and added to by the people of the archipelago.

3.1 Drift nets

In the 1850-1944 period we see the emergence of an autonomous response space (Huntington et al. 2017) and corresponding innovations in coastal technology i.e. drift netting and the rääkipaatti boat needed for the practice. This is compatible with Campling and Colás (2021) who identify commodity frontiers as spaces that motivate the creation of new innovations, in this case new types of boats and associated fishing gear.

The development of this type of fishing gear and related fishing methods had originated in the large island of Gotland, Sweden in the early 1800s. The fishers of Merikarvia Municipality in Finland learned of the practice from their colleagues from Åland. The sea is an open highway of trade, commerce and innovations (Campling and Colás 2021) and news about a new way of fishing for Baltic herring travelled fast to Oura. The fishers adapted this new approach slightly and developed their capacity to self-produce the means of harvest, i.e. the boats and the nets.

The successes of the first 80 years of operating this drift net fishery made the coastal town Merikarvia ‘the fishing capital of Finland’.

Over 300 crews participated in harvests that produced millions of kilograms of Baltic herring each year and was a source of wealth and income for the fishers. This discovery deviates somewhat from the experiences of traditional communities living and operating elsewhere in the world’s oceans that Campling and Colás (2021) have analysed. The Oura fishers had means of self-regulation and an autonomous ability to regulate their lives at sea. There position was very different from that of subordinated the macro production workers who formed part of fishing crews in temperate and tropical seas. The biogeographical and geological features of Oura favoured local knowledge and seasonal settlement patterns that provided catches but did not eliminate key features of the local culture or natural resource regimes.

However, this was to change. After the Second World War, Finland had to pay war reparations to the Soviet Union (Mustonen 2014). In order to do so, waged labor opportunities that would support the generation of wealth to repay these debts became more available on the mainland. Many fishers started to take new economic opportunities in, for example, the timber and construction industries. Many changes followed. Nets that were once made in the communities of the Oura Archipelago were replaced by the arrival of nylon and plastic gear. Boat types also changed. Between 1944 to the 1990s Oura’s drift net industry was modernized. The dependencies created by capitalist approaches and markets – e.g. on the capital-intensive purchase of nylon and plastic nets rather than the knowledge-intensive creation of community-made nets – shifted the drift netters and seal hunters closer to what Campling and Colás (2021:2) have called “constant circulation with spatial fixes that secure surplus creation”.

In the early part of this era small-scale coastal fishers could still maintain a relatively autonomous response space (Huntington et al. 2017) in terms of their reactions to natural changes, sea conditions, micro-market demand and supply of fisheries. These elements ultimately structure the nature, extent and quality of a fishery, and therefore the ordering, re-ordering and maintenance of the biocultural landscape of Oura at large (Loring 2017, Campling and Colás 2021).

Towards the latter part of this period – the 1970s to 1990s – Baltic fisheries were modernized. Trawling fleets arrived and began to monopolise the harvesting of a large portion of the Baltic h erring stocks. As a result, the role of drift netting changed. It ceased to play a major economic role as it had done, though it was still practiced by some local fishers. Rääkipyynti, the drift netting, was a symbol of local pride, innovation and self-esteem. As changes took place, Whitefish gained importance as a fish species that could still be caught using drift nets and the Baltic herring’s importance diminished. This ability to ‘pivot’ between species as a means to maintain a culturally significant form of fishing can be read as a symbol of resistance to the forces and mechanisms Campling and Colás (2021) have identified as having influenced larger fisheries around the world.

Figure 4. Samuli and Mikko Veneranta at fish traps for Baltic Herring, 1970s. Photo: Matti Pitkänen, used with permission.

The end of the drift net fishery in Oura took place between the 1990s and 2009. In 2009, The European Union banned all drift netting in the Baltic to protect the Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) and the stocks of dolphins in the far-away Mediterranean, in ignorance of the significance of drift netting for the people of Oura. Unfortunately for Oura’s fishers, their fishing grounds lie within the extreme northern edge of the Baltic harbour porpoise’s known range. The artisanal Oura drift net fishery became, therefore, collateral damage in a large-scale, well-meaning conservation decision designed to protect a critically endangered porpoise whose core habitat lies far from Oura in the waters of the southern Baltic, as Campling and Colás (2021) demonstrate.

This decision remains a bitter topic in the Oura Archipelago. In the late 2010s, Finnish fishery authorities visited the Oura islands from Helsinki and met with the remaining fishers in the archipelago. In response to the Helsinki authorities’ inquiries, local fishers responded that any form of cooperation would be possible the second the drift net fishery was re-legalized (Mellanoura et al. 2023). Their response reflects the reality that the ban on drift-netting in Oura has severely limited the self-capacity (Huntington et al. 2017) of the fishers to order and re-order their biocultural landscape. The ban on drift netting has rendered the fishers’ direct and regular engagement with the archipelago’s outer sea a memory and the open sea fishery an artefact of cultural heritage, rather than a living, self-replenishing process of engagement with the sea’s seen and unseen dimensions.

3.2 Seal hunt

Oura has been a seal hunting hotspot for centuries. The earliest archaeological findings from the region indicate engagements with the Ringed and Grey Seals that dates back at least 4000 years. We do not know the ethnic composition of these first hunters (Broadbent 2010, Sellheim 2018). However, it can be said with certainty that the Sámi Indigenous people are the first human society we know of to hunt seal in the area (Broadbent 2010).

The Oura hunt was, at first, a sacred act – an engagement with one of the most meaningful symbols of the sea, the seal. Mellanoura et al. (2023) among many other authors (Mäkinen and Mustonen 2004), have remarked that, despite the fact that the seal hunt had an economic incentive (seal oil, funds to support the hunt, skin, meat), hunters well into 1900s maintained ceremonies, taboos and other practices in their relations with the seal that indicate a sacral dimension to their hunting activities.

As in the case of drift netting, until the end of the Second World War (for Finland 1944) seal hunters were able to self-organize their engagement with the landscape and to maintain their self-capacity to regulate and determine the hunt (Huntington et al. 2017) in the ice scapes of Oura and the Bothnian Sea. This was the case in large part because the regulation of seal stocks, in a modern sense, was very underdeveloped.

Economic incentives, such as funds paid by the government for dead seals, affected the financial component of the hunt. Declining prices for seal oil in the 1800s reflected the switch to seal hunting nets. For a while, netting was a more economically viable method of harvesting seals in Oura, enabling hunters to save ammunition and therefore reduce costs. Despite these market-based adjustments, the period between 1850 to the 1940s can be seen as a time during which hunters operated an autonomous seal hunt.

Culturally, relations with seals changed in a significant way. Despite the individual hunters maintaining an ‘older’ set of beliefs and practices, the advent of the use of large open fish traps, accessible to seals, made the seal a more prominent competitor to the fishers of Oura. This technological arrival led to a shift in the seal’s cultural position from a prized and valued symbol of the sea into a pest. As previously mentioned, the disappearance of the seal from local diets in 1968 (Mellanoura et al. 2023) is indicative of the seal’s change in status.

In the late 1960s, toxic pollutants produced by newly-built pulp factories contributed to a decline in seal numbers that was quickly noticed by the seal hunters of the northern Baltic. Seal hunter Evald Geust (2021) from the Quark Archipelago north of Oura, described his observations of decline:

“In the 1960s we could no longer see a lot of pup hair on the ice from the ringed seals. This was due to the environmental pollutants. We no longer saw the areas where pups usually had stayed. Many seals were also tagged. We noticed many seals had a nasty wound resulting from the tag around their back flippers in the early years. You could see bones through. This was in the early years.”

Evald observed a collapse of grey and ringed seal populations in the 1960s. Scientists found that pollutants were the root cause of this collapse (see Fischer et al. 2021). Hunters were also critical of the tagging programmes of the 1970s that, according to their observations, harmed the seals. The pollution impacts marked the cessation of the hunt in Oura until the 2000s.

The Ringed seal and the Grey seal were potent early symbols of the Oura biocultural landscape and the manner in which the local community ordered their spatial and temporal scales as a part of their traditional sea use and occupancy. As technological advances introduced the large, open fish traps used from the 1900s onwards, the once respected seal was transformed into a pest and a competitor from the point of view of those inhabiting and reliant upon a rapidly modernizing fishery. In general terms, this technological shift collapsed community-level cultural relations with this marine mammal, though some individuals maintained ‘older’ memories and practices rooted in respect and veneration.

The seal acted as a conceptual ‘engine’ of the Oura self-ordered seascapes and landscapes until the 1960s. This is despite the fact that relations were affected by external political ecologies, including pricing of seals, use of seal oil in products such as paints, and the local trade in seal skins. Hunters were able to maintain a practice that shifted in some ways, such as the move towards the use of seal nets in the 1800s and of special boats (Broadbent 2010), while maintaining ceremonies and taboos that formed the backbone of complex relations with the seal. These relations were regulated and controlled by the Oura hunters and the community themselves, not by outside agents (Huntington et al. 2017).

In the late 1960s and 1970s environmental pollution originating from factories such as the Vuori-Kemia factory producing iron sulphates in Pori and pulp mills elsewhere greatly altered the Oura landscape (Saiha and Virkkunen 1986). This can be seen both as an external physical intrusion and a socio-cultural shift where the actual existence of the seals was threatened by the society beyond Oura, its economic choices and its production and externalisation of impacts, such as pollution events.

In the period from the 1970s to 2010, Grey seal populations have rebounded (Sellheim 2018). Due to the changes of the 20th Century, many of the Oura fishers today see the seal as a pest responsible for a reduction in their own catches. The old culture of respect for seals is buried deep, though it still exists in the memories of some old men. Occasionally permits for seal hunting from boats are issued, but this should be seen as a modern hunt, not a direct continuation of the older tradition.

Recent innovations in fishing technologies, such as the push up traps that have an entry blockade that prevents seals from entering to eat the fish, have begun to ameliorate the seal-fisher conflicts in Oura. In the 2020s the modernization of the fishery and the use of technological solutions determine the ordering of seal – human relations, in addition to the protection of the species (Campling and Colás 2021). Fishers also receive subsidies and compensation from the state against reported damages caused by the seals (Loring 2017, Metsähallitus 2022).

3.3 External Protection of Oura Archipelago

In the 1990s the European Union designated the Oura Archipelago as a EU Natura 2000 area. In 2011 the Bothnian Sea National Park, totalling 940 square kilometers, was established and Oura was included in the Park’s scope. This formalized the existence of a conservation policy for the archipelago, administered by an external governance agency – the State of Finland (Metsähallitus 2022). Campling and Colás (2021) point to how conservation targets are decided in capitalist metropoles, far from the local communities. Through this process distant waters are appropriated for the larger ordering of marine space and their governance is removed from their local biocultural matrices.

Prior to the 1990s and, to some extent, before 2011, the fishers and the community of Oura had self-ordered their biocultural landscape. For instance, local people adapted their artisanal fishery and its innovations to local realities and maintained a seasonal occupancy of the islands and adjacent seascapes. as well as specific, distinct cultural practices. Of these the most important were drift netting and seal hunting, which had enabled a relatively strong autonomous response capacity (Huntington et al. 2017). Others significant practices included berry picking in the outer islands, marine bird harvesting and other fisheries. Taken together, these practices enabled a marine coastal culture to exist and, in part, thrive.

The statutes of the Bothnian Sea National Park (Metsähallitus 2022) define the fisheries and nature protection in the park. Analysis of segments of the management plan and responses from fishing organisations enables us to trace the interface where ‘endemic’ (Mustonen 2014) notions of the ordering of Oura meet with the formal conservation logics of Parks and Wildlife Finland (Metsähallitus).

The management plan for the park (Metsähallitus, 2022) was co-developed with a range of entities the Finnish State called stakeholders. This included regional fishery representatives, including from Oura. The plan has, therefore, included aspects of co-produced (Johnson et al. 2015) management, inclusive of traditional and local sea knowledge. Metsähallitus (2022: 48) states that the hunt for Grey seal is possible with permits from Parks and Wildlife Finland. A quota for the seal has been established that regulates the numbers of animals harvested. Approximately 20-30 animals are now taken annually.

3.4 Commercial Fisheries in the Park and Emerging Threats

Metsähallitus (2022: 49) and the management plan highlight the importance of ‘commercial fisheries’ for the Park area. The plan states that the drift net fishery has been forbidden and this has reduced the gill net fishery significantly. The societal response has been the development of seal proof traps. Both Mellanoura et al. (2023) and Metsähallitus (2022: 48) express their concern for declining stocks, eutrophication and the role of Oura as a dynamic region having spawning areas and migratory fish, such as salmon. Metsähallitus (2022: 48) also refers to the hydrodams in the nearby rivers that have negatively affected fish and fishing.

Metsähallitus (2022: 86) determines that one of the foundational principles of the park is to protect fish and fish habitats. At the same time, the Park is seen to be a vehicle for maintaining a lively and thriving professional fishery. This is to be achieved through protection of habitat, regulation of harmful drivers and large-scale cooperation between authorities and fishers and local communities. Proliferation of the great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) is perceived to be one factor affecting the fishery, alongside climate and environmental actions, such as the installation of large wind turbine parks close to Oura.

3.5 Responses from the Professional Fishers

Metsähallitus (2022: 173) quotes the professional fishers of Bothnian Sea who scrutinize the park management plans and decisions. The fishers cite the principles of the Act on the Bothnian Sea Park (8.4.2011/326, 1§) and say that one of the key purposes of the conservation act is to maintain and protect also the professional fishery. Overall the fishers are satisfied in the joint discussions and co-creation of the Park management plan and look forwards being involved in the future iterations of the plan.

With the establishment of the EU Natura 2000 area and subsequent Bothnian Sea National Park in 2011, Oura is now formally recognised as an IUCN Strictly Protected Area. External entities from Helsinki and Brussels have exercised their capacity to decide the fate of this landscape as Campling and Colás (2021) demonstrate.

With the inclusion of Oura in the Park, which has a much larger geographical focus than the archipelago alone, these ‘Shining Islands’ are now managed as part of a 900 square kilometer conservation area. Here practices built over centuries and the unique biocultural landscape of Oura meet forms of external management rooted in science and policy that have the stated goal of conserving the islands (Loring 2017). The Park’s practical outcomes are yet to be seen.

Arriving at the present day, commercial fisheries and the seal hunt have changed (Sellheim 2018). The clearest interface between the internal landscapes of the islands and the external realm of conservation policy is the Park Management Plan (Metsähallitus 2022). The plan is seen rather favorably by the fishers and they feel they have been heard and been a part of a co-created process (Metsähallitus 2022: 173). This Plan contains echoes of the cultural knowledge and governance of the islands as they were realized during the heyday of drift netting.

- Conclusions

The political ecology and human interactions with the sea in the Oura archipelago are the product of shifting political, economic and social factors that have unfolded in recorded history between the 1850-2010s (Loring 2017, Campling and Colás 2021). Before the 1940s we can see how, due to geographical and social factors, the Oura case differs from the global assessment of marine capitalism Campling and Colás (2021) have proposed. The fishers maintained self-capacity, regulation, cultural concepts and an autonomous response space. In this inquiry Oura has been an interface between the world ocean analytics and the emergence of cultural and local processes from the archipelago.

We can identify the Second World War as a dividing line between the era of self-capacity and the fishers’ operation of a fully autonomous response space. Between 1944-1990s the modernization of society in Finland, environmental pollution and the proliferation of the cash economy altered the Oura fishery and seal hunt, two iconic practices that played a central role in maintaining key biocultural components of the landscape. However, some individual fishers chose to keep making their own nets and keep more ‘traditional’ practices. They still saw the sea as a crucial life force and a cosmic power.

The establishment of formal conservation practices, such as the ban on drift nets and the creation of a National Park between the 1990s-2010s contributed to the protection and conservation of species and the landscape of Oura as part of an externally driven, regional initiative. Loring (2017) charts similar experiences from Alaskan fisheries.

Reductions in endemic capacity and the introduction of further modernizing changes, such as Individually Transferable Quotas (ITQs) for marine fisheries, largely shifted the internal practices of the Oura Archipelago into the realm of cultural heritage. The proud symbols of the independent fishers – the rääkipaatti boat, seal hunt and the memories of the seasonal cycles on the Shining Islands – live on in the memory of the descendants of the fishing families.

Parts of this traditional knowledge has now been logged by the EBSA (Ecologically and Biologically Significant Marine Areas) process of the Convention of Biological Diversity under the United Nations – a global registry of important socio-ecological regions across the Earth’s seas and biocultural mapping (Mellanoura et al. 2023).

We can, of course, be critical of such external markers and their meaning. In their own turn they fix the localized into a globalized regime of oceanic governance and ways of knowing. Loring (2017) says that an ethical approach to fisheries requires that the state learns to be flexible with the concepts and categories it uses to govern fisheries. This needs to include sacrificing some level of legibility in favour of solutions that meet local needs and ensures that people do not have to fear for their well-being, even in extreme cases where sustainability requires that specific fishing practices or gear types be changed or abandoned.

His approach would be appropriate in Oura where, despite the co-creation of the Park Management Plan (Metsähallitus 2022), traditional knowledge and engagements with the landscape were, for the most part, approached from a generalist perspective. This challenges some elements of the deterministic nature of Campling and Colás’ arguments (2021) and their proposed terraqueous predicament, where earth’s geographical separation into land and sea has had significant consequences for capitalist development and has intensified the relationship between land and sea. It would counter the geophysical division between solid ground and fluid water, potentially opening new horizons.

Mellanoura et al. (2023) propose a set of reforms to regenerate the biocultural context of Oura. They mention, for example, the large ecosystem restoration of the river catchments that feed into Oura, inclusion of the traditional knowledge of the fishers in management, observations (Johnson et al. 2015) and economic incentives and increasing the capacity of young fishers to enter into the trade. Most importantly, building on the lessons learned in the Solent in the UK, Mellanoura et al. (2023) propose rewilding of the sea, following Clover (2022), with a particular focus on the spawning areas of the fish. This systems approach would deliver a political ecology solution to what Loring (2017) has proposed for marine systems’ resurgence in the 21st century.

In Oura the possibilities for achieving such comebacks are better than in many other places along the Baltic Coast. The Shining Islands may have a chance after all.

Figure 5. A rääkipaatti, made in 2010s, and fisher Timo Kuuskeri in the Oura archipelago, Summer 2022. Photo: Tero Mustonen, used with permission.

References

Alexander, K.A., Fleming, A., Bax, N. et al. (2022) Equity of our future oceans: practices and outcomes in marine science research. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 32, 297–311 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-021-09661-z

Broadbent, N (2010) Lapps and Labyrinths: Sami Prehistory, Colonisation and Cultural Resilience. Washington D.C: Arctic Studies Center

Campling, L. and Colás, A (2021) Capitalism and the Sea – The Maritime Factor in the Making of the Modern World. London: VersoClover, C. (2022). Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans. London: Witness books

Elands, B.H.M. , K. Vierikko, E. Andersson, L.K. Fischer, P. Gonçalves, D. Haase, I. Kowarik, A.C. Luz, J. Niemelä, M. Santos-Reis, K.F. Wiersum (2019). Biocultural diversity: A novel concept to assess human-nature interrelations, nature conservation and stewardship in cities,Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, Volume 40, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.04.006.

Geust, E (2021) Pitkät hylkeenpyyntimatkat. Vaasa: Osuuskunta Lumimuutos

Fischer, M., Maxwell, K., Nuunoq et al. (2022). Empowering her guardians to nurture our Ocean’s future. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 32, 271–296 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-021-09679-3

Huntington, H. P., A. Begossi, S. Fox Gearheard, B. Kersey, P. A. Loring, T. Mustonen, P. K. Paudel, R. A. M. Silvano, and R. Vave. (2017). How small communities respond to environmental change: patterns from tropical to polar ecosystems. Ecology and Society 22(3):9. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09171-220309

Johnson, N. et al. (2015). The Contributions of Community-Based Monitoring and Traditional Knowledge to Arctic Observing Networks: Reflections on the State of the Field, Arctic, https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4447

Loring, P.A. (2017), The political ecology of gear bans in two fisheries: Florida’s net ban and Alaska’s Salmon wars. Fish Fish, 18: 94-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12169

Mellanoura, J., Mustonen, T., Mustonen, K. (2023). Rääkärin maailma – Ouran kalastajien kulttuuriperintö. Vaasa: OSK Lumimuutos

Metsähallitus. (2022). Selkämeren kansallispuiston ja Natura 2000-alueiden hoito- ja käyttösuunnitelma. Vantaa: Metsähallitus

Mosby, Vinnitta, Bradley J. Moggridge, Sandra Creamer, Geoffrey Evans, Lillian Ireland, Gretta Pecl, Nina Lansbury (2025). Voices of hard-to-reach island communities provide inclusive and culturally appropriate climate change responses: A case study from the Torres Strait Islands, Australia, The Journal of Climate Change and Health, Volume 23, 2025, 100450,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2025.100450.

Mustonen, T, Mäkinen, A. (2004). Pitkät hylkeenpyyntimatkat ja muita kertomuksia hylkeenpyynnistä. Tampere: University of Applied Sciences Tampere

Mustonen, T. (2014). Endemic time-spaces of Finland: Aquatic regimes. Fennia – International Journal of Geography, 192(2), 120–139. Retrieved from https://fennia.journal.fi/article/view/40845

Mustonen, T. (2015). Communal visual histories to detect environmental change in northern areas: Examples of emerging North American and Eurasian practices. Ambio 44, 766–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0671-7

Mustonen, T., Maxwell, K.H., Mustonen, K. et al. (2022). Who is the ocean? Preface to the future seas 2030 special issue. Rev Fish Biol Fisheries 32, 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-021-09655-x

Pecl, G. et al. (2023). In print. Climate-driven ‘species-on-the-move’ provide tangible anchors to engage the public on climate change.

Saiha, Markku and Virkkunen, Juha. (1986). Kalastaja ilman merta – Into Sandbergin elämää ja kynänjälkeä. Porvoo: WSOY

Sandström, B. (2006). Jaktjournal Från Sälisen 1963-2002. Vaasa: Svenska Österbottens Säljagare

Sellheim, N. (2018). The Seal Hunt: Cultures, Economies and Legal Regimes. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff

Sundfelt, J, Johnson, T. (1964). Hylkeenpyytäjät. Helsinki: Weilin & Göös

Endnotes

[1] dominated by large land owners both in the Swedish Period, until 1809, and then the Grand Duchy of Finland under the Russian Empire, 1809-1917.