Pioneering theorist of geopolitics, Sir Halford J. Mackinder, long ago recognized the strategic interconnections between the Eurasian “heartland” (viewed by Mackinder as history’s primary “pivot area”), the “inner-” or “marginal-crescent” (called by many, most famously by Nicholas J. Spykman, the “rimland”), and the more distant “outer-crescent” of the world island, but left the frozen Eurasian Arctic region beyond this vital, dynamic and recurrently contested “pivot area” of the heartland, instead dubbing it “Lenaland” for its strategic isolation from the world island.[1] The Northeast Passage (of which the Northern Sea Route is part), and the offshore islands to its north, were, before the current era of profound and by many counts accelerating Arctic climate change, every bit as remote as “Lenaland,” of much future anticipated value but doomed by climate and geography to remain of minimal strategic importance while Ice Age conditions persisted in the Arctic. But with our era’s polar thaw, “Lenaland” itself has the potential to become a new extension of the heartland, and gain equivalency with the rest of this all-important pivot area, just as even more remote archipelagic regions of the Arctic long impenetrable to state power and thus of limited importance to world politics (particularly prior to the militarization of the global air, space and subsurface domains during the 19th and 20th centuries), may one day emerge as strategically salient rimlands.

Introduction: From Old Geopolitics to New – Arctic Island Chains, Global Security, and the Polar Thaw

That the Arctic was largely insular and archipelagic mattered less in the prior era of near-permanent polar pack ice than it does in our era of polar thaw, as the many islands and archipelagos that define the region’s physical geography remained locked in ice, in some cases all year round, and were thus perceived as strategic buffers due to their inaccessibility, more akin to the vast “wall of sand” defined by the Sahara than the dynamic (and frequently contested) Mediterranean basin. But this is decreasingly the case, and will in time profoundly transform the geopolitics of the Arctic and its strategic significance to the world, weakening sovereign claims to both the Northeast Passage (by Russia) and the Northwest Passage (by Canada) rooted in Section 8, Article 234 of the Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC) once they’re no longer perceived to be ice-covered areas. Indeed, with the disappearance of much permanent multi-year Arctic ice, it has become increasingly obvious that for the vast majority of the Arctic’s land, a defining geographical feature is increasingly its insular and/or archipelagic nature, comprised of multitudinous individual islets and islands that encircle the entirety of the circumpolar Arctic – as if stepping stones for future northern state expansion and development, and even potential conquest. This plentitude of tightly clustered archipelagos form increasingly strategic and salient island chains that must be held in order to defend against external threats or to deter them from rising altogether. In their aggregate, they in turn form a pan-hemispheric super-island chain, an increasingly salient foundation stone of the global order, each archipelagic component cluster with its own inherent tactical or regionally strategic value. These stretch all the way from the Aleutian Islands in the west to Wrangel Island in the east – between which can be found thousands of others from diminutive (44 square miles) Herschel Island just off the Yukon Territory’s north slope with its storied whaling era history and worrisome (to Ottawa) year-round American commercial presence; and the even smaller Hans Island (0.5 square mile), a rocky outcropping midway between Canada’s Baffin Island and Denmark’s island colony of Greenland which has been amicably contested in a neighborly way by both Ottawa and Denmark through what some have dubbed their “whiskey wars”[2] as the armed forces of each nation leave their liquor of choice – Canadian whiskey, or Danish schnapps, along with their respective national flags – upon departure for their rival to enjoy upon their next arrival); or the slightly larger Grimsey (2 square miles), just off Iceland’s northern shore, straddling the Arctic Circle and making Iceland, by its possession, a bona fide Arctic state.

To the immediate north is Greenland, the world’s largest island – greater in area than the next three largest islands combined (New Guinea, Borneo and Madagascar); and to the immediate west are respectively, Canada’s Queen Elizabeth Islands (where a controversial Cold War resettlement of Inuit families from northern Quebec took place, which critics have described as a callous deployment of “human flagpoles” to strengthen Canada’s sovereign claims to this lightly settled region) in the north[3] and Baffin Island toward the relative south; and farthest west in Arctic North America is the relatively newly settled Banks Island at the western entrance to the Northwest Passage, which has known modern Inuit habitation only since the early 20th century, when schooners brought Inuit trappers over in search of white fox.[4] To Greenland’s immediate east, of course, is the independent and formally sovereign island state of Iceland, and further east is Jan Mayen island, a remote outpost of Norwegian sovereignty, followed by the multinational treaty-governed island of Svalbard (formerly Spitzbergen), formally under Norwegian rule but bound by treaty to remain unmilitarized and to provide full and equal economic access to all treaty signatories, resulting in a permanent though declining Russian economic and consular presence there – and whose proximity to Russia’s northwestern frontier and gateway to both the Northern Sea Route and Russia’s submarine bastion at Murmansk, has long been recognized as a strategic island. Further eastward are the numerous islands and archipelagos off Russia’s mainland – including Franz Josef Land, Novaya Zemlya (so isolated that it served as one of the Soviet Union’s above-ground atomic testing grounds during the early Cold War years), the Zapovednik Islands, Severnaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, and Wrangel Island, among others, where Russia has been busily fortifying its defense installations after they were mothballed at the Cold War’s end.

Arctic Islands, Archipelagos, and Island Chains: Foundation Stones of a More Secure World

Maintaining control over these many islands, archipelagos and island chains of the Arctic and adjacent gateway regions is of increasing importance to not only the security of the Arctic region, but to global stability and world order itself. They present fixed geographical nodes – much as the many insular “unsinkable aircraft carriers” that have been attained and fortified by expanding world powers since the colonial era, and most notably by the United States since its defeat of the Spanish and its rise as a Pacific and later a truly global power – that are essential to homeland defense, and to the dissuasion and deterrence of aggression and other coercive behaviors by external rivals. Here, the Arctic states are especially well positioned by geographical endowment, owing to their firm and globally recognized (and largely uncontested) sovereignty over their respective Arctic lands, waters, and offshore islands, which in their aggregate ring the Arctic basin like a necklace, providing a protective barrier to each Arctic state’s territorial mainlands. It is true that much of the Arctic North America north of Canada’s mainland is either lightly settled or unsettled, with minimal state presence, and with complex histories of resettlement whose soreness still lingers generations later – and this could provide a weakness to otherwise recognized claims of Arctic sovereignty for potential exploitation, such as, hypothetically, by China much the way it did in the South China Sea. But in the latter, China fortified unoccupied islands adjacent to much weaker states lacking effective means of asserting sovereignty against a rival claim by China, while in the former, the islands of Canada’s High Arctic, like those off Russia’s mainland, or the sovereign and semi-sovereign island polities of the High North Atlantic, are internationally recognized – and Canada’s Arctic neighbors recognize its claims, just as Canada reciprocally recognizes the claims of its Arctic neighbors, with few, and largely insignificant, exceptions (mostly border disputes with neighbors who are, by and large, allies first and foremost). This unity of purpose and commonality of values, reflected in governing institutions and international fora across the Arctic (like the Arctic Council and the Arctic Coast Guard Forum), strengthens the Arctic as a whole and the intra-Arctic bonds between the eight sovereign states of the Arctic region.

This horizontal circumpolar collaboration has been enduring, and will likely withstand new external pressures, or hybrid (dual external/internal) pressures one can envision arising from the strategic triangularity of the competition for power between the United States on the one hand, and Russia and China on the other, as discussed so well by Canadian political scientist Rob Huebert.[5] It would thus be immeasurably harder for China to replicate its tactics as developed in the South China Sea, as doing so would almost certainly generate a universal rebuke from the entire membership of the Arctic Council, state and indigenous alike, and lead to China’s isolation – from not only the democratic Arctic states, but its partner-of-the-moment Russia – a consequence Beijing would find humiliating and which would show the fragility of Beijing’s current entente with Moscow. And while China may seek to influence, through its checkbook, the loyalties of indigenous communities across the Arctic, such efforts will likely catalyze a renewed effort by the democratic Arctic sovereigns to invest in the development of their northern frontier communities, as we saw after China sought to assert itself in Greenland recently,[6] which ironically not only precipitated the 2019 White House overture to “buy” Greenland from Denmark, which was initially widely criticized but led to a longer-term and more mutual diplomatic re-engagement between the United States and Greenland that has included the June 10, 2020 re-opening of the U.S. consulate in Nuuk for the first time since the 1950s, and an offer of US aid to help Greenland battle the pandemic threat from Covid-19. This suggests that Beijing will ultimately have to accept its place in the Arctic order as an outsider, a third-party observer state with maritime and commercial interests and many potential economic opportunities, but limited strategic, military, or diplomatic space for expansion.

A more concerted effort by the democratic Arctic states to court Moscow, through existing international institutions like the Arctic Council and the Arctic Coast Guard Forum, can greatly help toward this end. By strengthening ties within the Arctic states to their indigenous communities, and their relationship with fellow Arctic sovereign Russia, the members of the Arctic Council can greatly reduce the likelihood of experiencing a new, polar Cold War. Active participants in the Arctic Council and the Arctic Coast Guard Forum, which already have established a solid foundation for enduring intra-Arctic collaboration, are especially well positioned to take the lead on these initiatives, with deep and broad traditions of indigenous engagement to build upon. While the previous Cold War divided not only the Arctic but much of the planet into competing military-diplomatic-economic blocs, today’s world is much more integrated and much less likely to bifurcate again – and the added unity fostered by the long and continuing processes of Arctic globalization and economic integration will ultimately trump whatever regional advantages China may seek – so as much as Beijing may persist in its pursuit of such advantage, with continued unity among the Arctic states, China will in the end emerge both humbled and disappointed by the results of its efforts.

Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers: From Cold War to Collapsing Cryosphere

The distinctive and strategically important geopolitics of islands, archipelagos, and island chains – perceived as “unsinkable aircraft carriers” since the early Cold War, and in the aggregate as foundation stones of global security today – undergird and reinforce much strategic thinking with regard to emerging zones of maritime and naval competition around the world. This is particularly evident in recent years in the Arctic Ocean amidst the continuing (and by some measures, intensifying) polar thaw, with its circumpolar chain of archipelagos forming natural bridges between the continents, where they have played an outsized role in human history from prehistoric times up to the present. With the polar thaw, these maritime geopolitical structures are re-emerging from the ice in their primordial insular form, transforming the Arctic region and fostering its reconnection to the world ocean.[7] By understanding the geopolitical significance of these marine geographical structures, and their enduring importance to a stable world order, we can better contextualize the emerging strategic importance of the Arctic region, in addition to other remote and peripheral regions in the world.[8]

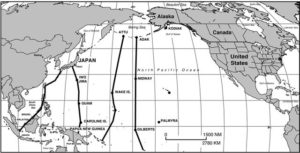

There has been much attention paid to island chains in discussions of Chinese naval strategy in recent years, and Beijing’s ongoing fleet modernization and naval expansion from its proximate first island chain (running from Japan all the way to the island of Borneo) on out to its more distant, mid-Pacific third island chain as PLAN continues its evolution full throttle from regional brown water fleet to an impressively robust blue water naval power [see Figure 1 and 2 below].[9]

Figure 1: The First and Second Island Chains

Increasingly, PLA Navy strategists refer to the island chains along PRC’s maritime perimeter, with the first connecting the island of Borneo, Taiwan, the Ryukyus (Okinawa) and Kyushu (Japan’s southernmost main island) and the second extending from eastern Indonesia to Japan’s main island of Honshu via Palau, Guam, the Northern Marianas and Iwo Jima. More recently, the third island chain has entered the lexicon as PLAN achieves a more capable blue water presence. Source: Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military Power of the People’s Republic of China, May 23, 2006, http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/china.html.

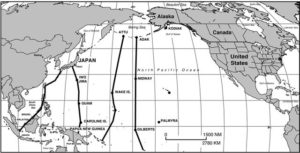

Figure 2: Beyond the Second Island Chain

Island Chains within the Western Pacific Ocean. Beyond the first and second island chains are a third, running north through Wake Island to Attu in the western Aleutians (which was invaded and occupied by Japan during World War II), and a possible fourth connecting the Gilberts, Midway and Adak. Source: Martin D. Mitchell, “The South China Sea: A Geopolitical Analysis,” Journal of Geography and Geology 8, No. 3 (2016), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306527696_The_South_China_Sea_A_Geopolitical_Analysis.

But island chains are an old feature of maritime geopolitics, dating back to well before the colonial era and have been as central to America’s strategic expansion across the Pacific as they were to the imperial Japanese, and before them, the British. American appreciation of island chains intensified during World War II, and achieved its zenith during the Cold War, after consolidating our hard-fought gains in World War II and dismantling Japan’s Pacific empire through an effective island-hopping campaign enroute to our final confrontation with Japan, itself an archipelagic nation, which culminated in the bloody battle of Okinawa and the subsequent atomic strikes on the island of Kyushu), while defending multiple strategic Atlantic Islands (Greenland, Iceland and Britain) from German attack.

America’s Cold War force structure and its geographic distribution consolidated these World War II victories, integrating the continued security of America’s island and archipelagic partners from Britain just offshore the European mainland to Taiwan at the doorstep to Asia’s mainland to that of the United States.[10] While America’s preferred allied partner, Britain, withdrew as a global hegemon, London nonetheless augmented America’s efforts through its own interventions in oceanic Southeast Asia, where it defended an independent Malaysia and Singapore from expansionist Indonesian nationalism in a low-intensity struggle for the stability of the Malay archipelago, to its liberation of a British-ruled Falkland Islands from Argentinian conquest (or, as Argentina viewed it, unification of mainland Argentina with its lost offshore possession – a struggle that parallels in many ways America’s own efforts to defend an independent Taiwan from what Beijing perceives as its rightful reunification.)

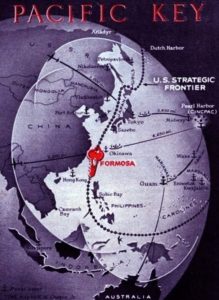

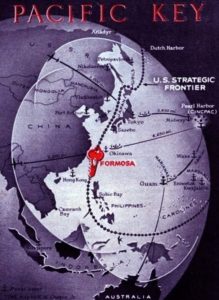

Figure 3: Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers

This image, from the Twitter account “Son of Taiwan” illustrates the strategic importance of Taiwan as an unsinkable aircraft carrier and submarine tender early in the Cold War, and a key to U.S. power projection across the Pacific to mainland China. Source: Son of Taiwan Twitter Account, https://twitter.com/sonoftaiwan/status/1138028385714630656/photo/1

Securing strategic island chains has been a fixture of America’s containment strategy since the dawn of the Cold War and continues to this day, and China has, by many accounts, embraced our own doctrine of island chain security with gusto, with island chains now perceived in Beijing as strategically vital outposts for asserting its own military control, and containing American influence. Providing more than a network of “unsinkable aircraft carriers”[11] – as Taiwan was famously described during the early Cold War [see Figure 3 above], and a term that has been applied to a diverse constellation of strategic islands that include Britain, Malta, Iceland, the Aleutians, Japan, and Singapore in addition to myriad South Pacific islands and atolls during World War II and the Cold War, in addition to the many islets of the South China Sea fortified by Beijing in recent years [see Figure 4 below] – island chains punctuate the worlds oceans much the way frontier forts punctuated the seemingly endless expanse of forest and grassland of the American West, providing essential forward offshore supply depots; safe harbors for repairs, recovery and maintenance; and air strips for power projection and over-the-horizon air defense – a strategically advantageous and well-fortified zone of persistent presence, force resilience, and effective control of surrounding air and sea space as central to recent Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO)[12] strategies as they were to our island-hopping efforts in World War II.

Figure 4: China’s New ‘Fleet’ of Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers

Borrowing from the United States’ strategic concept of unsinkable aircraft carriers used effectively to contain China during the early Cold War, the PRC has assertively embraced the concept, applying it to its chain of fortified islets in the South China Sea in recent years. Source: David Todd, “New satellite imagery shows Chinese ‘unsinkable aircraft carriers’ built on Spratly Island reefs, Seradata.com, August 9, 2016, https://www.seradata.com/new-satellite-imagery-shows-chinese-unsinkable-aircraft-carriers-built-on-spratly-island-reefs/

Figure 5: Beijing Erects a ‘Great Wall of Sand’ across the South China Sea

A March 16, 2015 satellite image from CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative illustrates China’s “Great Wall of Sand” under construction in the South China Sea. Source: All Things Considered, “‘Great Wall Of Sand’: China Builds Islands In Contested Waters,” NPR, April 10, 2015.

A modernized version of the offshore coaling stations central to Mahanian naval strategy, well-defended islands and archipelagos can be costly to neutralize during war, and in time of peace become de facto a zone of unrivalled economic, diplomatic and political influence, and a stepping stone toward further strategic expansion. This importance of island- and archipelagic-control to the ability of larger states to project military power, defend trade routes, assert diplomatic influence, and contain regional rivals, explains why Beijing has fortified so many islands and archipelagic clusters in what has been dubbed its “Great Wall of Sand”[13] in the South China Sea [see Figure 5 above], and has shown a comparably strong interest in the strategic-economic integration of its “String of Pearls” that arcs across the Indian Ocean – and why in turn Moscow has done much the same to its own chain of Arctic islands to the immediate north of Russia’s mainland.[14] That both major powers and leading rivals to western influence sense this same vulnerability and opportunity suggests they share a view of geopolitical theory and its intersection with naval strategy, one that the West is now again cognizant of as it was during the Cold War, and moving to counterbalance. This also explains why the White House, amidst the many paralyzing challenges of the present global public health and economic crisis, has mustered the renewed energy, foresight, and policy attention to reassert and clarify its Arctic (and Antarctic) interests, as expressed in its June 9, 2020 memo on Arctic security (“Memorandum on Safeguarding U.S. National Interests in the Arctic and Antarctic Regions”)[15] – which was aligned with, preceded by just one day, the re-opening of an American consulate in Nuuk, Greenland for the first time since 1953 – and why just a year before, it briefly floated an unsolicited bid for what the business community might liken to a hostile takeover of Greenland from Denmark (which Denmark quickly rejected),[16] while around same time anteing up over a billion dollars in funding for its long-anticipated icebreaker modernization program, renamed, appropriate to the contemporary challenge of projecting American sovereignty across an increasingly contested Arctic region, the Polar Security Program – providing a platform for sovereign assertion with the mobility to reach into the deepest of pack ice, from the shores along the Arctic basin all the way to the North Pole.[17]

Stepping Stones to Everywhere

But beyond the Arctic, in places where tensions remain between America’s armed forces and the communities that host their foreign bases, China rightly perceives an opportunity for strategic expansion without conquest. Its overtures to elites in a long list of remote island, archipelagic, and coastal nations as part of its global Belt and Road Initiative, from its “String of Pearls” to its “Great Wall of Sand,” will invariably yield new economic partnerships from which a closer strategic integration will follow. The onus thus falls to America and its allies to ensure that the many indigenous polities that host its global military presence feel appreciated for their contribution to the current international order. It is their hearts and minds that are essential to America’s continued ability to project military power globally, and to secure western values along the way.

This will require a continued and determined diplomatic effort, and a generosity of investment that can match China’s BRI. It is an arena of strategic competition with which it is intimately familiar, from its early global expansion through to the long, and successfully managed, Cold War. More recent challenges during the Global War on Terror, which presented a series of setbacks to American power on the global stage and precipitated a humbling crash course in counterinsurgency warfare and human terrain mapping, when considered amidst China’s strengthening rise and Moscow’s resurgence, suggest the coming global struggle for the hearts and minds of remote, indigenous islanders around the world – whose homelands are critical nodes for effective global naval operations – will not be easy, but that does not mean it is a lost cause. With a concerted effort, and a clarity of strategic vision – fueled by a proper understanding of maritime geopolitics and the continued (indeed, increasing) strategic saliency of island chains to international order – victory for the West is every bit as possible as it was during the Cold War.

Beyond Strategic Triangularity: Indigenous Peoples, Transnational Polities and the Human Terrain of the Arctic

As noted above, there has been much recent discussion of a triangular strategic competition in the Arctic between the United States (whose interests have remained, historically, in alignment with its democratic Arctic allies) on the one hand, and Russia, whose interests have recently overlapped (if not entirely aligned) with China on the other, as pioneered by Rob Huebert’s introduction of The New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment (NASTE) [see Figure 6 below].[17] The latter pair of rivals to western influence are widely perceived to have the advantage of momentum, with the former playing catch-up. In this sense, the Arctic region, as it rejoins the world ocean with the continuing polar thaw, mirrors the strategic alignment between Beijing and Moscow evident across much of maritime and continental Eurasia. As Alaska Public Media reported last year, “China and Russia are teaming up to pursue their interests in the Arctic, and regional security expert Rebecca Pincus says the United States needs to pay more attention” – though, as Pincus noted, these “two countries have overlapping interests that don’t always align.”[19] In her Spring 2020 Strategic Studies Quarterly article, “Three-Way Power Dynamics in the Arctic,” Pincus further elaborates that the “Arctic is an important locus for great power competition and triangular balancing between the US, China, and Russia. It is what political science professor Rob Huebert has dubbed the ‘New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment’ in which ‘the primary security requirements of the three most powerful states are now overlapping in the Arctic region,’ raising tension.”[20]

Figure 6: The US-Russia-China Strategic Triangle

The strategic triangle defined by the pendular diplomatic-strategic relationship between the United States, Russia, and China dates back to the Cold War, and has re-aligned several times. Currently, Canadian political scientist Rob Huebert sees it extending into the increasingly active Arctic basin. But the author of this article believes this overstates the importance of China in the Arctic, while understating the importance of the state-tribe interface across the Arctic basin to the region’s stability. Source: Liu Rui, “China-US-Russia Triangle,” Global Times, October 29, 2018.

While Huebert’s “‘New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment” is an elegant concept, the reality of Arctic geopolitical competition is much more complex, multilevel, and asymmetrical than the parsimony of trinitarianism can explain. Indeed, instead of a tidy triangle of competing sovereign powers, the Arctic region’s strategic competition can be more accurately visualized as an irregular strategic polygon with a dynamic mix of (largely) stable bilateral, trilateral and multilateral interstate relations, with the added complexity of an overlapping but largely invisible (to outsiders) set of internal and transnational fault lines of conflict. Many of these underlying dynamics are indeed triangular, but at the regional level or interlinking a different trinity of actors. By focusing exclusively on the three-way great power dynamics as Huebert and Pincus do, one can miss the many important triangular dynamics at the regional and local levels that can pit state and non-state interests against one another. Indeed, if we apply tripolarity as a lens to understand Arctic power dynamics, it is essential that we do so at the regional and local level. By adjusting our focal length to identify regional and local power competitions across the Arctic, we will find it can be helpful to clarify what at a higher level looks like complexity – for instance, the Washington-Tokyo-Ryukyus (Okinawa) triangle, the Beijing-Tokyo-Moscow or Beijing-Tokyo-Washington triangles (each a subset of larger strategic quadrangle), or the Washington-Moscow-Aleut triangle – each of these regional triangles complicates the over-arching GPC triangle that Dr. Huebert pioneered, paving the way forward for an expanding conversation on strategic triangularity at multiple levels of analysis that overlap and interact in fascinating ways.

These yield a diverse but largely collaborative group of predominant stakeholders that includes Arctic and non-Arctic states (inclusive of their national, regional, and local governments and major economic actors), indigenous peoples’ organizations (some holding regional and local governing powers), and numerous issue-specific NGOs. These operate within an environment marked by dynamically shifting alignments of interests, and a complex patchwork of governing systems with extreme variance and volatility over time. This is especially evident when examined village by village, region by region, and country by country, yielding a complexity that eludes easy explanation or simple strategic dictum.[21] While triangularity may elegantly describe one of the many salient levels of analysis in Arctic geopolitics (that between the three major world powers), this trinity of major states comprised by the US, China and Russia is anything but equal when it comes to their relative power and influence in the Arctic. Indeed, there China, as a non-Arctic states, is in the most important ways not even a significant player, with no Arctic territory of its own, and no seat at the Arctic Council’s table owing to its status as an observer state. This is in marked contrast to Russia, whose Arctic territories are the world’s largest, or the United States, which in alignment with its Arctic NATO partners (Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland and Norway) presents a formidable and historically united bloc [see Figure 7 below]. It is along these sovereign shores that all proposed marine shipping routes in a warming Arctic will pass [see Figure 8 below]. Indeed, as the Arctic continues its historic thaw, its archipelagic nature becomes increasingly apparent [see Figure 9 below].

Figure 7: The Arctic 8 (A8) Span from West to East across the North

This map illustrates the relative scale of Arctic territories of the “A8,” the founding states with full membership in the Arctic Council since its formation in 1996. China is not only not an Arctic state, but its status at the Arctic Council is only as an observer, a rank shared with states as small and far from the Arctic Circle as Singapore, and only since 2016. Source: Drishti IAS, “Arctic Council,” September 17, 2019, DrishtiIAS.com, https://www.drishtiias.com/important-institutions/drishti-specials-important-institutions-international-institution/arctic-council.

Figure 8a: Archipelagos and Emergent Arctic Sea Lanes

As the Arctic opens to increasing maritime traffic, and new shipping lanes emerge, the archipelagic nature of a warmer Arctic becomes increasingly clear, as does the strategic importance of the Arctic’s many islands, archipelagos, and increasingly strategic island chains. The defense and security of these islands, and the shipping lanes they abut, has been of increasingly recognized by the Arctic states as a strategic priority. Source: Source: NOAA, The Arctic Institute.

Figure 8b: Archipelagos and Arctic Defense Modernization

As the Arctic basin becomes increasingly active, and perceived to be of increasing value, Arctic states are redoubling their efforts to defend their Arctic territories, both on their mainlands and offshore, as depicted by Gary K. Busch below. Source: Gary K. Busch, “Russia’s New Arctic Military Bases,” Lima Charlie News, https://limacharlienews.com/russia/russia-arctic-military-bases/

Figure 9: Archipelagos and an Ice-Free Arctic

The Arctic without ice, though unlikely to be experienced before mid-century and then only briefly, reveals a maritime domain defined by islands, archipelagos and increasingly strategic island chains comparable to the Pacific and Atlantic.

If there is going to be a rumble for the Arctic and for control over its emergent sea lanes and vast, untapped repositories of natural resources, it will be a more complex, nuanced, and asymmetrical struggle. Indeed, it is likely to be defined by a concerted multilateral (if not fully aligned) effort by all eight sovereign Arctic states (inclusive of Russia) in response to rising external interest and pressures from an expanding group of non-Arctic states (inclusive of China). All eight Arctic states will not only endeavor to assert effective and meaningful sovereign control over their respective portions of the Arctic, but to also persuasively demonstrate both their individual and collective capacity to secure and defend their Arctic claims from future external threats. And at the same time, the seven Arctic states (all but Iceland) with an indigenous population will endeavor to successfully manage indigenous claims and aspirations for greater domestic engagement and inclusion that, if left unresolved and without achievement of a stable domestic alignment of state and tribal interests, could be exploited by these very same external states looking north to their future economic and strategic needs. It is this potential for exploitation of indigenous claims and aspirations by non-Arctic states that presents the greatest threat to Arctic stability, and which could become the contested battlespace for a future Arctic Cold War.

Foundations for Arctic Stability: Multilateralism at the Top of the World

With all eight of the Arctic states accepting the international legal framework established by the Law of the Sea Convention (LOSC), even without, as in our case, formally signing onto the treaty – with particular enthusiasm at and since the first Arctic Oceans Summit at Ilulissat over a decade ago, where the “A5” states littoral to the Arctic basin mutually pledged to adhere to LOSC – the region as a whole remains remarkably stable, and largely uncontested with the exception of several persistent but relatively low-intensity border disputes over the finer details of baselines and maritime boundaries. And though of some economic significance (such as the effect of the boundary demarcation on ownership of offshore petroleum reserves in the Beaufort Sea along the Alaska-Yukon northern boundary), with the universal and mutual circumpolar embrace of LOSC, these lingering border disagreements present virtually no escalation risk, in marked contrast to the transformation of the maritime geopolitics of the South China Sea due to Beijing’s unilateral fortification of numerous contested islands.

Consequently, the United States and Canada can continue to disagree over their Beaufort Sea boundary as well as the legal status of the Northwest Passage while at the same time jointly participating in undersea mapping (in preparation for their respective LOSC claims), search and rescue, and joint military exercises across the region. And, Canada and Denmark (Greenland) can continue to disagree over who governs Hans Island, the tiny outcropping of rock midway between the two, while maintaining a strong, friendly, and growing bilateral diplomatic relationship and partnership within NATO. Additionally, Russia and Norway can amicably settle their historic border dispute amidst intensifying tensions between Russia and NATO,[22] and Russia and the United States, principal adversaries during the Cold War era, can jointly manage their long, and thus far stable, maritime boundary between Alaska and Siberia.[23] (In 2017, Russia and the United States established a joint management regime for safe shipping,[24] through what might otherwise present a geopolitical vulnerability with potential to become every bit as significant and worrisome as that found in the Malacca Strait, presenting a narrow strategic chokepoint right at the Pacific gateway to both the Northern Sea Route and the Northwest Passage.[25])

Local tensions may rise and fall, but the broader tenor of amicable international Arctic relations remains notably stable when compared to other regions of the world, and the role of China is at best a peripheral player in the Arctic basin. The multilateral cooperative tradition between Arctic states is nicely illustrated by the 2011 Arctic Search and Rescue (SAR) Agreement agreed to by the eight member states of the Arctic Council, which coordinates SAR coverage and response in the Arctic, and establishes areas of SAR responsibility for each state party – again without any role to play for non-Arctic states, inclusive of China. Parallel to the Arctic Council in structure is the Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF), which provides a forum for the coast guards of all eight Arctic states, which despite rising diplomatic and military tensions, have sustained strong bilateral cooperation in their maritime relations.

As described by Andreas Østhagen on the website of The Arctic Institute, “For both Norway and the US, coast guard cooperation with Russia is placed in the context of long-standing bilateral relationships as maritime neighbors in the Arctic. Having formalized cooperation through the exchange of information and joint exercises, the cost of tearing down decades of relationship-building in the Arctic was considered too high by both Norway and the United States. Neighboring states are dependent on dialogue across borders which, in turn, must be kept somewhat separate from the domain of overarching international diplomacy. That this cooperation survived the tensions over the on-going conflict in Ukraine is indicative of as much.”[26] And yet, even amidst this strong tradition of intra-Arctic cooperation between once and future rivals, there has been a marked shift in strategy by the Arctic states in recent years, and a return of a more pragmatic and defensive realism, with national interests again driving decision making. This is illustrated by Washington’s recent policy and budgetary recommitment to an icebreaker modernization program to enhance its capacity to assert sovereignty further offshore in the rapidly warming Arctic, and in its flurry of new bilateral diplomatic initiatives with the world’s largest island, Greenland, standing guard over North America’s northeast flank.

This is equally illustrated by Moscow’s recent fortification of its long-ignored offshore Arctic islands, newly perceived to be a vulnerable island chain of increasingly strategic importance to Russia’s resource and trade economy, and to the territorial integrity of Russia’s mainland. A key driver of these efforts is, of course, the Arctic climate, and in particular the rapidity of the polar thaw. One need not make any assumptions about either the cause, or the end state, of the dynamic climate instability observed in recent years across the Arctic to recognize the military implications of a warming Arctic, and the risks, uncertainties and insecurities revealed with the continuing thaw.

Hearts and Minds: The Looming Battle for the Arctic’s Human Terrain

If there is a system-wide vulnerability that could be exploited by a diplomatically skilled and economically powerful external actor, it would most likely be found in the least populous and most remote areas of the Arctic, such as Canada’s vast Arctic archipelago north of the Canadian mainland, where the Inuit have in recent decades steadily gained more powers, and in 1999 achieved the formation of their own autonomous territory, Nunavut, a vast territory of increasingly strategic lands and waters with a tiny population of just over 40,000. Also vulnerable to external machinations is neighboring Greenland, which has been undergoing its own incremental (and thus far amicable) process of decolonization between its majority Inuit populace and its colonial sovereign, Denmark – and whose small population (just over 50,000) lacks the domestic capacity to effectively defend its vast EEZ (a challenge even for Denmark, itself a small state with a population under six million).

One can envision a comparable vulnerability on both the Arctic mainland of North America and Eurasia, where many struggling interior and coastal villages dot these vast, underpopulated, and disconnected regions, forming isolated islands of humanity separated by vast distances of open, unoccupied space, with an insularity that is as isolating as that on the populated offshore Arctic islands. In these vast archipelagos, real or metaphoric (in much the same way that renown Russian literary giant, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, perceived Siberia, hence the title to his classic book, The Gulag Archipelago), a struggle to win over the hearts and minds, and thus the loyalty, of the locally predominant indigenous peoples there, and which continue to share a distinctive isolation, largely absent of the same intensity of settler pressures as experienced in more populous regions to the south, could emerge as the next salient fault line of conflict, internally dividing each of the otherwise stable Arctic states.

A similar fault line is now apparent, particularly retrospectively, in the outer Aleutians three quarters of a century ago when Japan invaded and occupied the predominantly Unangax̂ (Aleut) islands of Attu and Kiska, and bombed Dutch Harbor on Amaknak Island, home to the Dutch Harbor Naval Operating Base, and U.S. Army’s Fort Mears.[27] As a an example of what was perceived as a “triangular” strategic contest between the armed forces of imperial Japan on the one hand, and the United States and Canada on the other, the indigenous Unangax̂ people were caught in the middle and at the time perceived by combatants on both sides as peripheral to the conflict, the opposite of the “human flagpoles” resettled to Canada’s unoccupied high Arctic Queen Elizabeth Islands in that they were displaced by both warring parties to distant detention centers, with some forcibly relocated to Japan for the remainder of the war (where around half perished), while most were forcibly relocated (ostensibly for their own protection) by American forces – their very own sovereign protectors – to distant, cold and excessively damp detention camps in Southeast Alaska. There, some ten percent of the population died, and many of the survivors were later prevented from ever returning to their home villages, deemed to be economically unviable in the post-war era.[28]

Such tragic consequences to an indigenous populace caught in a war zone between the armed forces of Imperial Japan and the United States were, unfortunately, all too common in World War II, from the liberation of the Aleutians, the first island chain to be retaken from the Japanese in 1943, all the way to the final battle of Okinawa, where once more, the determined forces of the United States wrestled back from Japanese control the Ryukyu Islands, better known as Okinawa, at high cost to the local indigenous population that found itself trapped between these two warring parties much the way the Unangax̂ were. In the case of the Ryukyuans, and endured staggering losses estimated at half their prewar population of 300,000, far more than the 110,000 Japanese and 12,500 American soldiers lost. In the postwar years, America’s military presence in Okinawa, essential to both Cold War and post-Cold War security in the Pacific, has continued to face determined local opposition, as the rift created during the Battle of Okinawa has never completely healed, even three quarters of a century later.

Similar tales of dispossession and exile took place across the Canadian Arctic and in Greenland as well, creating rifts between the Inuit and Ottawa as well as Copenhagen (and Washington, too, which was responsible for the defense of Greenland during World War II and the Cold War, resulting in some displacement of the Inuit of Thule) comparable to that caused by the Unangax̂ displacement in the Aleutians during World War II, and just as slow to heal.[29] The consequences were universally tragic for the Inuit and Unangax̂. As the Qikiqtani Truth Commission has described: “For Inuit, the loss of home is more than the loss of a dwelling — it is a disruption of a critical relationship of people with the land and animals. It represents the loss of independence and replacement of a way of life.”[30]

Understanding the historical context and near universality of this internal fault line across the Arctic thus elevates the strategic saliency of this internal fault line of conflict within the Arctic states, and present a potentially exploitable vector for external manipulation and destabilization that could disrupt the internal balance of power between far-away national and regional governments of the “center” on the one hand, and the isolated indigenous villages (whether on the continental mainland, or offshore – each in its own regional archipelago of sorts) of the “periphery” – forging a new axis of conflict that could come into play during a period of intensified strategic competition in the Arctic. This is true whether a campaign of hybrid warfare of the sort mastered by Moscow in recent years, or the “pocket book” diplomacy (or, the more malicious “debt-trap” diplomacy) favored by China, or the less likely scenario of a formal state of war between rival states for control of the Arctic domain, as experienced during World War II with the Japanese occupation of the outer Aleutians, and narrowly avoided by allied successes in both the Battle of Britain, and the Battle of the Atlantic, which prevented German expansion toward North America [see Figure 10 below].

Figure 10: The Arctic as a ‘Fourth World’ Defined by Continuing Indigenous Inequality

Challenging living conditions in the Arctic, and wealth and health gaps between Arctic communities and their southern counterparts, have given rise to the term “Fourth World”, as evident in the title of Sam Hall’s book, The Fourth World: The Heritage of the Arctic and its Destruction (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987).

Colonial States and Sovereignty by Proxy: Indigenous Polities and Political Order

Whether in the Arctic, or further south throughout the world ocean, such tensions and vulnerabilities are commonplace. Thus, some are felt by American forces in the Pacific, from Guam to Okinawa; and others by allied partners who maintain their own offshore bases on remote islands across Oceania. The Chinese, as they expand their influence, find themselves facing similar tensions and vulnerabilities along indigenous fault lines, creating a vast, interconnected theater of strategic competition where local indigenous polities gain what may seem to be outsized importance to the international order. While their populations and territories may be relatively small, they are nonetheless locally predominant, and essential partners to the security of the entire Pacific basin, just as they are to the security of the Arctic basin.

The perceived triangular strategic rivalry pitting Washington’s interests against those of Moscow and Beijing presumes an inherently “Westphalian” unity of the Arctic states, but this is far from the case in much of the Arctic, where most of the states are not unitary nation-states. They are instead former colonial states cobbled together in earlier centuries by the unitary states of the Westphalian core as they reached across the seas, leaving indigenous peoples and their local governing structures largely intact and enabling colonial rule via local (and for the most part, corporate trading) proxies. Limited in manpower and dependent upon native hunters and trappers to exploit the region’s bounty of furs, the colonial era chartered companies preserved intact prior power relationships and networks of the precolonial world that would be successfully leveraged in the interest of ascendant colonial powers. Because this remains a defining feature of most of today’s Arctic states, a lingering fault line remains between center and periphery, largely aligning with the settler elites in command of the state apparatus to the south, and the indigenous communities in the remote hinterland that have been gradually restoring their self-governing powers (with the one notable Arctic exception being Iceland, which was settled prior to the arrival of the eastward migrating Inuit, leaving this one Arctic state as a truly unitary Westphalian polity). Understanding this internal dynamic, and achieving a stable balance of interests through inclusive and respectful policies of native enrichment and empowerment, may be of momentous consequence in the event of external agitation by a non-Arctic state.

This historic struggle for the human terrain of the Arctic is thus of great importance to the future stability of the region, and requires forward thinking investment, respectful relationship-building and sustainment, and a continuous process of confidence-building measures to ensure that the legitimacy of the rule of the sovereign states of the Arctic remains intact and uncontested, lest a foreign interloper such as China seeks to destabilize the status quo. Because of the many socioeconomic challenges facing northern villages from one end of the Arctic to the other, this is a potential vulnerability that an external power could seek to exploit – and, some argue, has already become a target for exploitation by Beijing. Because these northern indigenous homelands have been imperfectly integrated with the political economies of the Arctic states, despite much progress and ongoing efforts in recent years, this remains a near universal fault line across the Arctic, and a challenge faced by the seven Arctic states that have indigenous populations engaged in long-term processes of cultural renewal, economic development, and restoration of land rights.

Progress on this front varies greatly by region and by state, offering an uneven opportunity for external exploitation. While Russia has in recent years mastered the art of hybrid warfare below the threshold of formally declared war, as demonstrated in its persistent but low-level interventions along the arc of what it once referred to as its “near abroad”[31] and with particularly effective results in Crimea, and Beijing has similarly deployed “checkbook diplomacy”[32] to coopt elites along the global network envisioned by its Belt + Road Initiative (BRI), including its northern component, the Polar Silk Road, the latter has faced strong blowback against what the United States and its allies have successfully reframed as “debt-trap diplomacy,”[33] while the former has on its own generated a near-universal distrust, particularly by states bordering Russia that fear they could become the next Crimea. In short, tactical blunders by both Moscow and Beijing, through their clumsy and overconfident efforts to coerce small polities and peoples, have blunted their capacity to project power into the Arctic (with the exception, of course, of Moscow’s own Arctic territories and waters, where its sovereignty remains uncontested, but where it remains far behind its democratic Arctic counterparts in reconciling state and tribal interests).

Indigenous Engagement and the Containment of China’s Arctic Ambitions

Intriguingly, the strengthening alignment of interests between indigenous peoples and their sovereigns across the non-Russian Arctic from Alaska to Finland can provide the democratic Arctic with an advantage over Russia, whose own native peoples remain marginalized, their lands and resources encroached upon or expropriated, and leaders remain exiled.[34] One can even imagine the democratic Arctic states mastering in turn the art of hybrid warfare, just as many by necessity re-mastered the art of counterinsurgency warfare during the long Global War on Terror (GWOT),[35] and by turning the tables on Moscow, winning the battle for the hearts and minds of Russia’s own oppressed native peoples, a process already underway to a limited degree with the warm diplomatic reception enjoyed by Russian indigenous leaders in Arctic governing institutions like the Arctic Council, where Arctic indigenous organizations enjoy a distinct membership status as Permanent Participants, second only to the founding member states (the A8), and superior in organizational status to the many observer organizations and states, among which China is included [see Figure 11 below].

Figure 11: The Battle for Indigenous Hearts and Minds

Human terrain mapping (HTM) became central to U.S. strategy during the Global War on Terror and its many battles to win indigenous hearts and minds. In 2010, James Der Derian (with David and Michael Udris) released “Human Terrain,” a film that explores the US Army’s Human Terrain Teams and its ‘cultural turn’ in counterinsurgency. In the United States’ intensifying strategic competition with Russia and China, worldwide and in the Arctic, HTM may once again provide a strategic advantage. Source: https://geographicalimaginations.com/2012/12/18/project-z/

But more likely, Russia will eventually realize that its security will be better strengthened by achieving parity with its democratic counterparts on the Arctic Council in the area of native rights and empowerment – already evident in its latest Arctic strategic outlook to the year 2035 (with indigenous issues are mentioned at least 13 times)[xxxvi] – and in so doing, the inter-Arctic collaborative dynamic can be strengthened – further eroding the significance and saliency of the triangularity described above.

With its deep pockets, China may take the opportunity to retool its approach, shifting away from the naked power grab of debt-trap diplomacy to foster a more mutually beneficial model of Arctic economic development, positioning Beijing to more adeptly exploit any failures by the Arctic states to sufficiently support and re-empower their own indigenous peoples, who are intimately aware of any unevenness in Arctic social, cultural and economic development, a shift already achieved at the rhetorical/articulated-policy level in its 2018 Arctic white paper but not yet evident in its ground game. So a triumph by the democratic Arctic states is by no means guaranteed with regard to the battle for indigenous hearts and minds; but they still have many advantages over Russia and China that could make it impossible for either of these rivals to meaningfully undermine western influence in the region, or to dilute the sovereignty they have over their respective Arctic territories.

Thus, if there is indeed a new Cold War in the Arctic region – and many believe there already is one – the home front in each of the Arctic states, where continued gains in native development will be crucial for the political legitimacy, territorial integrity, and political sovereignty they assert, will be an important arena of engagement, one where the United States and its allies have many advantages that provide the opportunity to consolidate victory and ensure unrivaled regional supremacy through more inclusive and effective governance – in partnership with the indigenous peoples of the Arctic [see Figure 12 below].

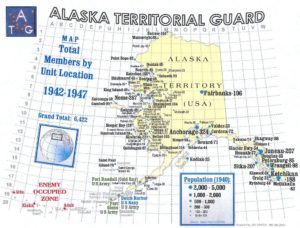

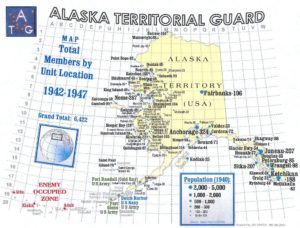

Figure 12: Alaska Territorial Guard: “Guardians of the North”

Left: “Guardians of the North” (left) as depicted by Mort Kunstler. Source: Guardians of the North, https://www.nationalguard.mil/Resources/Image-Gallery/Historical-Paintings/Heritage-Series/Guardians/; Right: Alaska Territorial Guard map by Jay Griffin, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Alaska_Territorial_Guard_map.jpg. The ATG, also known as the Eskimo Scouts, was a military reserve force component of the U.S. Army, organized in 1942 in response to Japan’s attacks on Pearl Harbor and later the Aleutian Islands. Its members represented 107 Alaska communities with Aleut, Athabaskan, Inupiaq, Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, Yupik, and non-native peoples united in their common defense of Alaska, with official membership topping six thousand, and unofficial counts exceeding 20,000.

References

[1] For a current discussion of Arctic geopolitics, see Nebojša Vuković, “Do we need revision of the key geopolitical paradigms?” Medjunarodni Problemi (International Problems, published by the Institute of International Politics and Economics, Belgrade, Serbia)72, No. 1 (2020): 15-36. In the author’s Arctic Doom, Arctic Boom: The Geopolitics of Climate Change in the Arctic, Mackinder’s conceptual vocabulary is discussed in application to the warming Arctic. There is a robust literature on geopolitical theory that discussed Mackinder and Spykman, including their own influential works, including Mackinder’s Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction (New York: Holt, 1919), reissued in 1996 by NDU Press, and his “The Geographical Pivot of History,” The Geographical Journal, Volume 23 (1904), 421–37, as well as his final work, “The Round World and the Winning of the Peace,” Foreign Affairs, Volume 21 (1943), 595–605 are a good place to begin, as is Nicholas J. Spykman’s The Geography of the Peace (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1944) and America’s Strategy in World Politics: The United States and the Balance of Power (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1942) along with his articles, “Geography and Foreign Policy, I,” American Political Science Review (1938, Issue 1) and “Geography and Foreign Policy, II,” American Political Science Review (1938, issue 2), (with A. A. Rollins) “Geographic Objectives in Foreign Policy, I,” American Political Science Review (1939, issue 3), (with A. A. Rollins), “Geographic Objectives in Foreign Policy, II,” The American Political Science Review (1939, issue 4), and “Frontiers, Security, and International Organization,” Geographical Review 1942, issue 3. Spykman’s scholarly contribution was remarkably prolific given his untimely death in June 1943.

[2] Dan Levin, “Canada and Denmark Fight Over Island With Whisky and Schnapps,” New York Times, November 7, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/08/world/what-in-the-world/canada-denmark-hans-island-whisky-schnapps.html

[3] For detailed histories of Canada’s Inuit “exiles”, see Melanie McGrath, The Long Exile: A Tale of Inuit Betrayal and Survival in the High Arctic (New York: Vintage, 2008), or for a more critical view of the conventional narrative, see Gerard I. Kenney, Arctic Smoke and Mirrors (Ottawa: Voyageur Publications, 1994).

[4] For a detailed history of the island, see John Bockstoce, White Fox and Icy Seas in the Western Arctic: The Fur Trade, Transportation, and Change in the Early Twentieth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019) and Peter J. Usher, The Bankslanders: Economy and Ecology of a Frontier Trapping Community (Ottawa: Northern Science Research Group: Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1970)

[5] See Rob Huebert, “The New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment (NASTE): Ramifications for Canada,” Special Senate Committee on the Arctic, Ottawa, April 3, 2019.

[6] For more on China’s rebuffed efforts to coopt Greenland, see Drew Hinshaw and Jeremy Page, “How the Pentagon Countered China’s Designs on Greenland,” Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2019, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-the-pentagon-countered-chinas-designs-on-greenland-11549812296.

[7] For an in-depth discussion of these macro-level systemic changes to the Arctic, see the author’s Arctic Doom, Arctic Boom: The Geopolitics of Climate Change in the Arctic (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2010). For an understanding of the interconnected geopolitics of islands and archipelagos and its significance to world politics, consider the pioneering contributions and analytical framework of Sir Halford J. Mackinder, in addition to more recent critical geographical approaches that share an underlying appreciation of the role of islands and their security in international order. To help island studies, also known as nissology, take form as an academic discipline, the International Small Islands Studies Association (ISISA) was formally established in 1992 and this past summer (2020), the very first ISISA Global Island Studies Webinar (GISW) was held on June 24-25, 2020, with 31 consecutive hours of panel presentations in nearly every time zone, with the author participating on a panel discussing the future of Greenland chaired by his colleague from the University of Akureyri’s Polar Law Centre, Jonathan Wood, who is also contributing to this special issue of NoMe. For a discussion of the origins of the field of nissology, see Oscar Campomanes, “The Islandic in the Postcolonial Critique of American Empire,” https://uchri.org/foundry/the-islandic-in-the-postcolonial-critique-of-american-empire/, an essay that emerged from the Fall 2017 meeting of the University of California Humanities Research Institute (UCHRI)’s Asia Theories Network, “Island Life.” Campomanes notes that nissology is “derived from the Greek root for island, nisos and study of, logos,” and “is defined as ‘the study of islands on their own terms.’ This field has multiple centers in unlikely locations, often islandic themselves, and therefore not in the metropolitan ‘mainstreams’ of theoretical and practical knowledge-production.”

[8] This is true not only of the Arctic ocean, but also as far south as the Austral (Antarctic) Ocean , where the security implications of the alliance integration of so many isolated islands, archipelagos, and island chains bears a striking similarity to these respective challenges facing the top of the world today, as they do to the challenges of remote maritime regions around the world. Numerous observers over the centuries have been outspoken and articulate evangelists for appreciating the strategic importance of Alaska and the Arctic to American security, from the architect of the 1867 purchase himself, Secretary of State William H. Seward, to the early apostle of air power and founding father of the USAF, CDR William L. “Billy” Mitchell, along with veteran Arctic scholars such as Oran R. Young, a pioneer in the study of global environmental governance and regime theory in international relations, with regional expertise in the Arctic.

[9] See the prolific work of James R. Holmes and Toshi Yoshihara, including Red Star over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010), in addition to their many articles, such as “Responding to China’s Rising Sea Power,” Orbis, Volume 61, Issue 1, 2017, Pages 91-100; “Asymmetric Warfare, American Style,” Proceedings, April 2012 (Vol. 138), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2012/april/asymmetric-warfare-american-style; and “Responding to China’s Rising Sea Power,” Orbis, Volume 61, Issue 1, 2017, Pages 91-100; and Toshi Yoshihara, “China’s Vision of Its Seascape: The First Island Chain and Chinese Seapower,” Asian Politics and Policy Volume 4, Issue 3 (July 2012), Special Issue: How China’s Rise Is Changing Asia’s Landscape and Seascape, 293-314, among others.

[10] In fact, it was General Douglas MacArthur’s public articulation of an island-chain strategy for America in the postwar Pacific in 1950, amidst hostilities in South Korea and asserting the strategic importance of Formosa (Taiwan) as part of an allied island chain linking the Philippines to Okinawa, that precipitated his dismissal by President Truman. See “Texts of Controversial MacArthur Message and Truman’s Formosa Statement,” New York Times, August 29, 1950, 16. Such an island chain, MacArthur argued, if “properly maintained would be an invincible defense against aggression.” It is here that MacArthur famously described what is now known as Taiwan as “an unsinkable aircraft carrier and submarine tender” whose strategic importance had been clearly recognized and lethally leveraged by the Japanese at the “outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941,” and which, if it again falls to a power hostile to the West, “would repeat itself.” MacArthur’s vision reached beyond this first island chain to a hemispheric arc of islands pivotal to western security. In a widely cited quotation, Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow write that “MacArthur convinced George Kennan that the US should obtain complete control of Okinawa in order to establish a ‘striking force’ positioned along ‘a U-shaped area embracing the Aleutians, Midway, the former Japanese mandated islands, Clark field in the Philippines, and above all Okinawa.’” See their “Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific ‘Island Chains’,” The China Quarterly, January 2016, 6. In their “Why Islands Still Matter in Asia,” Erickson and Wuthnow note that MacArthur’s “island chain philosophy indeed encapsulates some important strategic thinking of the era,” adding, “Such thinking unquestionably influenced Chinese strategists as they sought to make sense of their nation’s geostrategic position, the security challenges it faced, and what it might do to address them.” See: “Why Islands Still Matter in Asia,” National Interest, February 5, 2016, https://nationaIinterest.org/print/feature/why-islands-still-matter-asia-15121.

[11] See the following for selected details: Michael O’Hanlon, “China’s Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers: While America builds carriers, China builds islands,” Wall Street Journal, August 6, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-unsinkable-aircraft-carriers-1438880237; Brad Lendon and Michelle Lim, “Japanese Island Could Become an Unsinkable US Aircraft Carrier,” CNN, December 6, 2019, https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/06/asia/japan-us-military-base-island-intl-hnk/index.html; Fighter Jets World, “Here Are The Unsinkable Aircraft Carriers Of The World,” June 28, 2020, https://fighterjetsworld.com/weekly-article/here-are-the-unsinkable-aircraft-carriers-of-the-world/22478/.

[12] For an introduction to EABO, see Marine Corps Association & Foundation, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) Handbook 1.1, June 1, 2018, https://mca-marines.org/wp-content/uploads/Expeditionary-Advanced-Base-Operations-EABO-handbook-1.1.pdf. For a discussion of EABO, see Robbin Laird, “Reshaping Perimeter Defense: A New Pacific Island Strategy,” Defense.info, August 12, 2019, https://defense.info/re-thinking-strategy/2019/08/reshaping-perimeter-defense-a-new-pacific-island-strategy/ or Laird’s co-authored book with Edward Timperlake and Richard Weitz, Rebuilding American Military Power in the Pacific: A 21st Century Strategy (Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio / Praeger Security International, 2013)

[13] This phrase generated worldwide headlines after being utilized in a speech by Admiral Harry B. Harris, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra on March 31, 2015, in which he observed China was “creating a great wall of sand, with dredges and bulldozers, over the course of months.” See “Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Admiral Harry B. Harris Jr., 31 March 2015, As delivered,” https://www.cpf.navy.mil/leaders/harry-harris/speeches/2015/03/ASPI-Australia.pdf. For an example of media coverage of this, see BBC News, “China Building ‘Great Wall of Sand’ in South China Sea,” April 1, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-32126840. For a recent discussion the “String of Pearls,” see Pankaj Jha, “Countering Chinese String of Pearls, India’s ‘Double Fish Hook’ Strategy,” Modern Diplomacy, August 8, 2020, https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2020/08/08/countering-chinese-string-of-pearls-indias-double-fish-hook-strategy/.

[14] Gary K. Busch, “Russia’s New Arctic Military Bases,” Lima Charlies News, https://limacharlienews.com/russia/russia-arctic-military-bases/.

[15] The White House, “Memorandum on Safeguarding U.S. National Interests in the Arctic and Antarctic Regions,” June 9, 2020, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/memorandum-safeguarding-u-s-national-interests-arctic-antarctic-regions/

[16] For further discussion of this initiative, see the author’s “Donald Trump is thinking of buying Greenland. That’s not necessarily a bad idea,” The Globe and Mail, August 18, 2019, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-donald-trump-is-thinking-of-buying-greenland-thats-not-necessarily-a/.

[17] For more details of the PSC program, see the USCG Polar Security Cutter program information page, https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/Assistant-Commandant-for-Acquisitions-CG-9/Programs/Surface-Programs/Polar-Icebreaker/.

[18] Rob Huebert, “The New Arctic Strategic Triangle Environment (NASTE): Ramifications for Canada,” Special Senate Committee on the Arctic, Ottawa, April 3, 2019. Also see Rebecca Pincus, “Three-Way Power Dynamics in the Arctic,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, Spring 2020, 40-63.

[19] Liz Ruskin, “China, Russia Find Common Cause in Arctic,” Alaska Public Media, March 21, 2019, https://www.alaskapublic.org/2019/03/21/china-russia-find-common-cause-in-arctic/

[20] Pincus, “Three-Way Power Dynamics in the Arctic,” Strategic Studies Quarterly, Spring 2020, 40.

[21] A good introduction to the complexity of Arctic governance can be found in Mathieu Landriault, Andrew Chater, Elana Wilson Rowe, and P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Governing Complexity in the Arctic Region (New York: Routledge, 2019).

[22] For more details on the joint US-Canada seabed mapping effort, see Sian Griffiths, “US-Canada Arctic Border Dispute Key to Maritime Riches,” BBC News, August 2, 2010, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-10834006; for a broader discussion of the multiple overlap disputes across the Arctic region, see Jessica Brown, “Thaw in accord: As Arctic Ice Melts, Territorial Disputes are Hotting Up, Too,” The Independent, March 1, https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/geopolitical-consequences-of-melting-arctic-ice-russia-canada-us-northern-sea-route-shipping-natural-a8229306.html. For a discussion of the history of American Arctic policy since the Cold War, see the author’s “U.S. Defense Policy and the North: The Emergent Arctic Power,” Chapter 12 in The Fast-Changing Arctic: Rethinking Arctic Security for a Warmer World, edited by Barry Scott Zellen (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, Northern Lights Series, 2013). or “Where East and West Converge: The US Embrace of Collaborative Security for the Arctic,” Chapter 28 in the Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic, edited by Leif Christian Jensen and Geir Hønneland (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015).

[23] Known as the Baker-Shevardnadze line since its formal demarcation by negotiation in 1990, it remains unratified on the Russian side due to the rapidity of the subsequent Soviet collapse, but has remained nonetheless adhered to throughout the post-Cold War era. See the UN, Agreement between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics on the Maritime Boundary, June 1, 1990, https://www.un.org/Depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/USA-RUS1990MB.PDF. In early 2020, it looked as if Moscow was contemplating ending its support of this still unratified agreement due to the Soviet collapse that quickly followed the treaty’s negotiation by then U.S. Secretary of State James A Baker, and his Soviet counterpart and last foreign minister of the USSR (and first leader of an independent Georgia), Eduard Shevardnadze, for whom the subsequent (and stable) “Baker-Shevardnadze Line” named. Paul Goble, “Moscow May Soon End ‘Provisional Enforcement’ of 1990 Bering Strait Accord With US,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Volume 17, Issue 12 (January 30, 2020), https://jamestown.org/program/moscow-may-soon-end-provisional-enforcement-of-1990-bering-strait-accord-with-us/.

[24] For an excellent summary of the 2017 agreement, see Emily Russell, “US, Russia Agree on Shipping Standards for Bering Strait,” Alaska Public Media, June 6, 2018, https://www.alaskapublic.org/2018/06/06/us-russia-agree-on-shipping-standards-for-bering-strait/; for the full details of the agreement, see: IMO Sub-Committee on Navigation, Communications and Search And Rescue, “Routeing Measures And Mandatory Ship Reporting Systems: Establishment of two-way routes and precautionary areas in the Bering Sea and Bering Strait,” Submitted by the Russian Federation and the United States, 5th session, Agenda item 3, NCSR 5/3/7, November 17, 2017, https://www.navcen.uscg.gov/pdf/IMO/NCSR_5_3_7.pdf. – building upon the even longer tradition of amicable maritime border relations that has been sustained between the Cold War’s principal adversaries, both during and after the Cold War.

[25] For more details on the joint US-Canada seabed mapping effort, see Sian Griffiths, “US-Canada Arctic Border Dispute Key to Maritime Riches,” BBC News, August 2, 2010, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-10834006; for a broader discussion of the multiple overlap disputes across the Arctic region, see Jessica Brown, “Thaw in accord: As Arctic Ice Melts, Territorial Disputes are Hotting Up, Too,” The Independent, March 1, https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/geopolitical-consequences-of-melting-arctic-ice-russia-canada-us-northern-sea-route-shipping-natural-a8229306.html. For a discussion of the history of American Arctic policy since the Cold War, see the author’s “U.S. Defense Policy and the North: The Emergent Arctic Power,” Chapter 12 in The Fast-Changing Arctic: Rethinking Arctic Security for a Warmer World, edited by Barry Scott Zellen (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, Northern Lights Series, 2013). or “Where East and West Converge: The US Embrace of Collaborative Security for the Arctic,” Chapter 28 in the Handbook of the Politics of the Arctic, edited by Leif Christian Jensen and Geir Hønneland (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015)

[26] Andreas Østhagen, “Coast Guard Cooperation with Russia in the Arctic,” The Arctic Institute, June 6, 2016, https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/coast-guard-cooperation-with-russia-in-the-arctic/.

[27] For a seminal history of the war in the Aleutians, see Galen Roger Perras, Stepping Stones to Nowhere: The Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and American Military Strategy (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2003).

[28] For a detailed and moving account of the Unangan displacement, see Carlene J. Arnold, The Legacy of Unjust and Illegal Treatment of Unangan, Master’s Thesis in Global Indigenous Nations Studies, University of Kansas, 2011.

[29] In addition to the publications cited in note 24 above, much insight can be gained from the documentary films by celebrated Inuit filmmaker, Zacharias Kunuk, including “Exile,” his 2009 documentary of the above-mentioned resettlement in the 1950s of Inuit from Kuujjuaq (then called Port Harrison) in northern Quebec to the then unsettled Queen Elizabeth Islands, over 1,000 nautical miles to the north, to found the communities of Resolute and Grise Fjord (Igloolik: Igloolik Isuma Productions, 2009, http://www.isuma.tv/isuma-productions/exile-0) and his 2018 documentary, Or his 2018 documentary, “Kivitoo: What They Thought of Us” (Igloolik: Igloolik Isuma Productions, 2018, http://www.isuma.tv/hwma/kivitoo/ep4kivitoo1) on the 1960s resettlement of the entire village of Kivitoo, on Baffin Island, to Qikiqtarjuaq, some 40 miles away.

[30] Qikiqtani Truth Commission. “Nuutauniq: Moves in Inuit Life. Thematic Reports and Special Studies Qikiqtani Inuit Association,” Qikiqtani Truth Commission website,

http://docplayer.net/55079820-Qikiqtani-truth-commission-nuutauniq-moves-in-inuit-life-thematic-reports-and-special-studies-qikiqtani-inuit-association.html.

[31] For discussions and definitions of hybrid warfare, see Jim Garamone, “Military Must Be Ready to Confront Hybrid Threats, Intel Official Says,” Defense.gov, September 4, 2019, https://www.defense.gov/Explore/News/Article/Article/1952023/military-must-be-ready-to-confront-hybrid-threats-intelligence-official-says/; and Alex Deep, “Hybrid War: Old Concept, New Techniques,” Small Wars Journal, March 2, 2015, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/hybrid-war-old-concept-new-techniques. On the “Near Abroad,” see William Safire, “ON LANGUAGE; The Near Abroad,” New York Times Magazine, May 22, 1994, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/22/magazine/on-language-the-near-abroad.html.

[32] Daniel S. Hamilton, “Checkbook Diplomacy,” The Diplomatist (2016), as reposted by the Center for Transatlantic Relations, https://archive.transatlanticrelations.org/publication/checkbook-diplomacy-daniel-s-hamilton/.

[33] For a discussion of China’s BRI and its association with debt-trap diplomacy, see Hadeeka Taj, “China’s new Silk Road or debt-trap diplomacy?,” Global Risk Insights, May 5, 2019, https://globalriskinsights.com/2019/05/china-debt-diplomacy/. For a discussion of Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s public rebuke of China in a speech during the Rovaniemi Arctic Council ministerial in May 2019, see Marc Lanteigne, “The US Throws Down the Gauntlet at the Arctic Council’s Finland Meeting,” Over the Circle, May 7, 2019, https://overthecircle.com/2019/05/07/the-us-throws-down-the-gauntlet-at-the-arctic-councils-finland-meeting/. The full text of Pompeo’s May 6, 2019 Rovaniemi speech, “Looking North: Sharpening America’s Arctic Focus,” can be found at https://www.state.gov/looking-north-sharpening-americas-arctic-focus/.

[34] On the struggles of Russia’s Arctic indigenous leadership, see Thomas Nilsen, “Russia Removes Critical Voices Ahead of Arctic Council Chairmanship, Claims Indigenous Peoples Expert,” The Barents Observer, November 27, 2019, https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/civil-society-and-media/2019/11/russia-makes-ready-arctic-council-chairmanship-removing-critical.

[35] For an historical and theoretical discussion of America’s long history of both insurgency and counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare, and its relearning the art of COIN during the GWOT, see the author’s The Art of War in an Asymmetric World: Strategy for the Post-Cold War Era (New York: Bloomsbury Academy, 2012).

[36] See the translation by the Russian Maritime Studies Institute at the Naval War College, “Foundations of the Russian Federation State Policy in the Arctic for the Period up to 2035,” March 5, 2020, https://dnnlgwick.blob.core.windows.net/portals/0/NWCDepartments/Russia%20Maritime%20Studies%20Institute/ArcticPolicyFoundations2035_English_FINAL_21July2020.pdf?sr=b&si=DNNFileManagerPolicy&sig=DSkBpDNhHsgjOAvPILTRoxIfV%2FO02gR81NJSokwx2EM%3D