We are quite used to observing and criticizing the politicians statements, their behavior, and even their personal appearance. We might take pride in not being naive and in recognizing how much they are twisting their arguments, omitting inconvenient facts and mistakes, generally polishing their own image, while promising how much good they will do for their voters and for the nation as a whole. We are usually aware that politicians are performing rhetoricians before the public and the recording cameras. In short we keep an eye on them and their rhetoric. But this may not be the only type of persuasion or rhetoric involved nor the only place to look: this paper argues that we should also look at what is going on behind the cameras in terms of camera technique.

Whenever a speech or a debate between politicians is broadcast live on television or offered to the general public as video clips on social media, an additional group of people join the production process, namely those handling the cameras, microphones and other technical equipment. The camera technicians and producers apply their professional skills, norms and procedures, and they make a lot of more or less conscious, natural or conventional, choices about how to place, operate, move and adjust the cameras in order to record and transmit the performance of the politicians. The point of this paper is to show that this placement and handling of the camera in each and every case has a significant influence on how the politicians will appear to the public.

This whole recording procedure may seem quite trivial, we may generally trust the camera people to follow aesthetic and technical standards and aim for “best practice” and a fair presentation. Of course we might suspect in special cases that a journalist or even a specific TV-channel may have very selective and slanted views of things, but generally we tend to trust reportages and video clips to be showing us what is going on, almost as if we were actually there ourselves. Thus we concentrate our attention on the politicians that we see “through” the camera. The camera itself is in this way usually transparent, and the work that goes into placing and handling it is generally unobtrusive, it seems natural and not worth discussing.

But just because the camera work generally goes unnoticed left to the smooth practice and skills of professionals technicians, it nevertheless contains a range of possibilities for supporting, enhancing, directing attention, suppressing or emphasizing what goes on in a debate or even in the seemingly simple reportage from a ceremonial speech. It should be of interest to an overall critical, rhetorical and phenomenological analysis of modern visual media to consider that cameras are always bound to be showing us politicians from specific (and sometimes significantly changing) points of view.

Skillfully conducted and in the right context a variety of camera movements, cuts, camera angles, and framing options (together with the work on the audio tracks) can influence or even construct what the audience will experience, and perhaps how they will evaluate the politicians and the process and outcome of a debate. In terms of rhetoric both logos, ethos, and pathos can be affected by the specific camera work. In the following a few fairly simple examples will be analyzed and discussed, starting out with the significance of zoom-in and zoom-out, then the point of view of the camera (including angles, height and framing – not in the journalistic, but in the photographic sense), and lastly the potential impact of reaction-shots (or shot/reverse shots).

It should be noted that the terminology used in this interdisciplinary paper is drawn from both classical rhetoric, communication theory, film studies, and video production. The overarching framework is an analytical phenomenological approach to the appearance of politicians on modern media, and the working hypothesis is that the work behind the camera plays an important role in creating the attention, the mood, the emotional impact, the reception, and understanding of political speeches and debates. On television and on social media the visual production set-up is constantly staging and framing politics, moving, passing, appealing, focusing, entertaining, and pointing out to us.

Zoom in and Zoom out

For decades the Danish Queen Margrethe II has been addressing the Danish population on national TV on New Year’s Eve. It is a live broadcast, always commencing at 18:00 hours and lasting some 10 to 15 minutes. It is a very ceremonial address, in terms of rhetoric the genre of her Majesty’s speech is epideictic, mostly a reinforcement of common (national) values, and perhaps some existential reflections about the passing of times. Her Majesty may also offer some slightly moralizing advice, e.g. about how to be kinder to each other. The Danish monarch is not supposed to act as a politician in any ordinary sense, however, the camera work involved in this very ceremonial broadcast may well illustrate how the authority and ethos of a speaker can be supported by the setting and operation of the camera.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvBvqR4D_xI&t=726s

The whole speech is delivered live in one take, i.e. addressed to just one steady camera placed in front of and in eye height of the queen sitting at a large desk. The are no cuts to other cameras during the speech and the one camera stays in the same position. But there is nevertheless one subtle move: soon after start the camera very gently zooms in, not to any extreme closeness, but semi-close. The camera starts from an overview of the stately room and the whole of the impressive desk where the queen is sitting, it then very slowly zooms in closer and stops at a moderate close up with the queen conventionally framed in a head and shoulder shot, much like a news reader or host on conventional TV-programs. Neither the point of view, the framing, nor the slow zoom in at the beginning of the speech stand out as remarkable.

It should be noted that there is a certain difference between a camera zooming in, as it is here on the queen, and a camera actually moving (travelling) closer to a speaker and keeping the same zoom setting, but this is in most cases not a crucial difference (however, the counter-operating of zoom and travel can be utilized for creating specific effects).

It is quite standard procedure in classical Hollywood film style (and in mainstream television today) to begin each scene or even a whole film or program with an overview shot of the location, and then to follow up with either a cut or a zoom in to some specific spot or person of interest. An overview shot at the beginning of a program serves much like an introduction or even a meta-communicative comment to the viewers about where we are and what is next to follow. As film theorist David Bordwell remarks, it is highly communicative: Typically, the opening and closing of the film are the most self-conscious, omniscient, and communicative passages (Bordwell, 1986). In terms of corporal phenomenology the camera can be said to imitate or mimic a person’s physical entering and overlooking of a room providing thus the television viewer with a (mediated, but) somewhat similar experience of entering and meeting the person at the desk.

The opening of the program offers a lot of information to the viewer, or, in order to avoid the misunderstanding that this “information” should be of a verbal or discursive nature, it would be better to say that the camera provides a view that immediately sets a tone and attitude: as viewers we sense a large room with stately furniture and decorations and a person sitting behind a grand desk gazing directly at us. This already sets a certain mood and tone in us, even before the first words are spoken. We may recognize the person or not, the view itself is likely to have a certain quality and impact, calling for attention or perhaps even awe and respect. Discovering a person looking straight at us, or turning towards us, always has a strong impact, it seems to be an instinctive reaction, rooted perhaps in our reptile brain parts or nervous system as well as in social norms and schooling. And in this case a strong set of cultural norms further adds to the impression: the noble decor, royalty, the position at the desk well known from meeting our schoolmasters and bosses, and the sort of “parental gaze” (Juel, 2004) that the queen is exercising, here in a rather kind and almost shy way. So, as viewers we have already perceived and felt a lot even before the first words have been spoken.

The slow zooming in on the speaking queen after a few seconds is a camera move that is both conventional (well-known from traditional films and programs) and at the same time very natural (mimicking the view we have when walking closer to a talking person in real life). There is no contradiction between the “conventional” and “natural” aspect of this camera move, indeed it goes hand in hand to explain why it passes so unnoticed (or “seamless”, as we may say about classical Hollywood editing). It is a curious fact, however, that we also accept that the sound remains the same (in terms of loudness and nearness to the microphone) even though we by means of the camera seem to move in closer to the talking person (from a theoretical and phenomenological point of view this way of connecting/disconnecting sight and sound in the experience of film media is an interesting and complex feature – even though it may at first seem trivial and “natural”).

In the 2017 version of the Danish Queen’s New Years’ address there is no zooming out at the end of the speech, the producer cuts to camera views from outside the castle. But it would have been quite in line with normal film and television procedure to mark the ending with a zoom out. Indeed this common camera feature can be seen as an instance of the general narrational principle of seeking a certain symmetry or balance to a story by returning at the end to something reminding of the initial location or state of affairs.

So, a zoom out at the end of a political speech or debate on television is quite standard procedure. One example of this is the German chancellor Angela Merkel’s New Year’s speech for 2018. During the entire main part of the 6 minute long speech the camera stays zoomed in at a fairly close head-and-shoulder shot. There are, however, within this main setting some very small movements in the zoom, hardly noticeable unless one runs the recording fast forward or backwards. This is not due to sloppy camera work, on the contrary it is just a skilled way of adding a bit of life to an otherwise rather stiff appearance of the speaker. These small adjustments – movements almost as if the camera was slowly breathing or adjusting its stance – can be seen in many other examples of portraying a politician on TV (even as early as 1969 as we shall soon see).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PfuKMpm6X8U

In the example with Angela Merkel the camera is again placed straight in front of and in eye height with her. This is standard procedure making her communicate as if directly to the viewers’ face. In terms of rhetoric the camera is supporting the ethos of the speaker, or at least not detracting anything, which would be the case if the camera was looking down at her, watching her from the side, or framing her not as the center of attention but as a marginal figure. To get an idea of the massive amount of conventions involved, and of the variable options for the camera to influence the viewers perception of the speaker, one just has to consider what would happen in case the camera all of a sudden zoomed in on the flowers on her desk, on a window in the building behind her, or began to dash around in a dizzying, hand-held amateur style.

The opening shot here with Angela Merkel at the center includes a view of some flowers to the left and some flags (German and EU) to the right, and we see a bit of the well-polished surface of a desk. Unlike the Danish queen, Angela Merkel appears to be speaking without manuscript papers in front of her, and she seems fairly relaxed and friendly in her attitude and appears to strike a rather confidential or familiar tone. It does not seem to be a very programmatic and political agenda setting appearance, but mostly a social and ceremonial one. But this may of course all be part of supporting the chancellors position and political status – and well thought through by some strategic advisers.

It is therefore worth noticing what the camera includes in the semi-total opening and ending shots, namely not so much the interior of a palace room, as in the case of the Danish queen, but a view outside behind the chancellor: here in the evening light we see at some distance in the background a large, representative building, including classicist pillars, a dome, and a tower with what appears to be – once again – the German flag at the top (actually it is the German Parliament, or Bundestag). So, it is literally on the background of, or in the setting of national political symbols (well known to the German viewers) that the chancellor this evening gives her seemingly very personal or family like address. In the whole long middle of the speech where the camera has zoomed in on the speaker, we may as viewers have forgotten this setting as we only see the person speaking – and perhaps also the lit Christmas tree and the lights of moving traffic making it all very seasonal and cozy: but then we are reminded again, when the speech is over and the camera zooms out giving us again a larger perspective.

Till now we have seen two main functions of the zoom in and zoom out of the camera: first and foremost these camera moves guide the viewers by marking the beginning and ending of the program, and together with the camera angle, framing and focus the movements help to point out the main person and to support her status. Secondly, we have smaller movements during the main body of the speech where the otherwise static camera adds a bit of life to the scenery by means of gentle adjustments of the fairly close zoom. These secondary small movements could be seen as aesthetic or in terms of Roman Jakobson they could be said to have a poetic function, whereas the main zoom in and zoom out can be seen as guiding the viewer by a mix of conventional, social, expressive and persuasive features, which in Jakobson’s terms would be phatic and emotive functions, perhaps even conative, as the camera handling adds to the impressiveness of the speaker (Juel, 2013). In terms of rhetoric the camera can be said to support or even perform an ethos appeal.

But also a third type of communicative function of the zoom in and zoom out can possibly be detected in some recordings of political speeches, as we shall see in a rather famous historic example.

The American president Richard Nixon gave a TV-speech from the White House on November 3rd 1969 about the war in Vietnam and a new policy he wanted to employ. This has become known as Nixon’s “the Great Silent Majority Speech” and has been much discussed and analyzed, not just politically but also in academic circles, so far, however, with little attention to the camera work involved.

What the audience saw in 1969 was an almost 32-minute long unbroken live transmission in color from a single stationary camera placed quite conventionally in flat front and eye height of Nixon. The opening shot is from a fair distance giving us an overview of the president sitting at a large desk with his papers, a telephone, and in the background the American and the Presidential Flag, a framed photo and a huge curtain; it is a familiar and easily recognized view of the Oval Office in the White House.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpCWHQ30Do8&t=752s

This framing and setting lends a lot of presidential authority to the speaker (the framed family photo adding also a “human touch”) , it seems conventional or even natural and is hardly noticed, but it should be remembered that a camera recording could have been made from a different angle (semi-profile), with a different framing (e.g. Nixon placed not in the center but to the far right), and the camera could in principle have been hand held and looking down on Nixon (but surely it would have been a poor idea for many reasons, also because the studio cameras were rather heavy at that time).

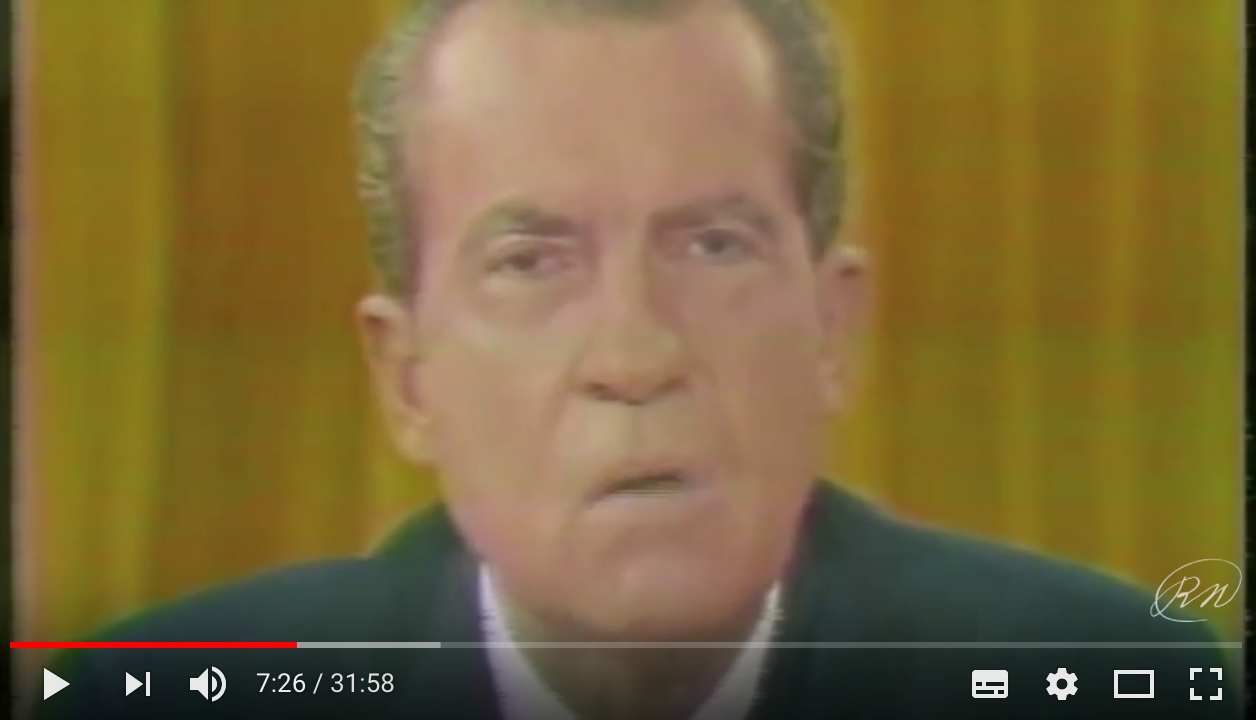

Again in this broadcast the camera soon after the opening lines zoom in closer. Here the zoom in actually brings us very close, at times Nixon’s face appears so fill almost the whole of the screen: the top of the frame cuts the top of his hair and the bottom cuts away his tie and all below. This is actually a bit unusual, at some points it seems really close, indicating perhaps that the camera crew tries its very best to make Nixon’s appeal on this crucial and sensitive issue a very personal and persuasive one.

The camera zooms in on Nixon’s face during his speech – at times it is very close.

That is of course an interpretation, the audience probably had very different reactions depending on whether they liked Nixon in advance or not, and depending on the audience’s view of the war effort. The camera moves are still to be seen, however, when we now review the video recording, they are so to speak objective features or part of the video text as such and open for analysis.

During Nixon’s long speech the camera is changing the zoom gently now and then as if moving a bit closer or away and thus adding some life or variation to the picture as we saw in the case of Angela Merkel. And quite as expected the camera retreats, or actually zooms out, when the speech is coming to an end following the traditional pattern of beginning, middle, and ending, where the beginning and ending call for an overview shot, whereas the middle calls for a closer and more focused look at the speaker and content. Or it could be said that the camera assists that the middle part of the speech is experienced in an immersive, intense, lively, or even personal way.

The recording of Nixon’s speech offers a special variation of the traditional overview ending: the speech seems to come to an end with a very solemn historical perspective and the camera zooms out in what seems a becoming and closely coordinated move as Nixon says “Fifty years ago, in this room and at this very desk, President Woodrow Wilson spoke words…”. But right after this comes the real ending with a renewed zoom in on Nixon’s face looking straight at the viewer and giving his final appeal trying to muster, no doubt, as much personal ethos and pathos as possible: “As President I hold the responsibility for choosing the best path…” So, the camera by its speech correlated move and emphasis can be said to try to convince us in a non-verbal visual way to have trust in Nixon’s political agenda and leadership.

A close analysis of the various small zooms in and zooms out during the Silent Majority Speech reveals another rhetorical tool embedded in the camera moves. Eleven and a half minute into the speech Nixon says that he will read from a letter, that he newly sent to Ho Chi Minh. The camera immediately marks that a quotation is now coming by a distinct zoom out almost back to the starting position, and the camera holds this position for about a minute, precisely until the quotation ends, and then the camera again zooms back in closer to Nixon. Here the camera work helps to clarify the content of the speech, much in the same way as a change in lay-out of a written text by means of indent, quotation marks, or italics could help the reader to understand the different level of the quotation. Again, the camera moves here are done in a skilled and professional manner, they do not draw any undue attention, but they do add to the overall rhetorical features of the TV-transmitted speech.

The camera zooms out – neatly coordinated with Nixon’s quoting from a letter – and then zooms back in.

This last function of the camera, where the zoom work obviously try to help the viewer understand the text of the speech, is hardly controversial, it can be seen as just very instructive, skilled and pedagogical, another tool for clear communication within the large box of possible visual and filmic features. However, at the same time it should be recognized that the different ways of visually portraying a speaker in terms of framing, focus, zoom movements, nearness-distance, angle, height, etc. have a large but generally unnoticed potential for influencing the reception of the verbal rhetoric.

Nixon’s “Great Silent Majority Speech” has been closely analyzed and discussed not just out of political or public interest, but also from an academic point of view. An example of this is Forbes Hill’s so called neo-Aristotelian rhetorical analysis that aims at disclosing whether the speaker makes the best choices: “…how well did Nixon and his advisers choose among the available means of persuasion for this situation?” (Hill, p. 384). Hill looks into the argumentative, structural, and stylistic verbal features, and even comments on the speech-writer’s literary skill and Nixon’s “tone” (the choice of words, etc.), but there is no treatment of the actual audio-visual features, no mention of camera work or setting or voice quality, or light: it appears that Hill’s analysis may just as well be based entirely on a written version of the speech and not on an actual viewing and listening. This means that Hill’s analysis in all its thoroughness misses an important part of the original text, this “text” being the actual tv-broadcast that reached the viewers in 1969 – a text that we can still review today thanks to the preserved video.

Camera work should be considered not just as a technical vehicle or aesthetic wrapping of words, but as an integral part of the rhetorical performance and potential persuasiveness of a political speaker. As an audience we basically see what the camera work has chosen to show us, and to show us in a specific way, but usually we are not critically aware of this selection and filtering of the visual presentation.

Point of view

Prior to the invasion of Iraq by the US and allies in Spring 2003 a number of debates were held in the United Nations Security Council. February 5th the US secretary of state Colin Powell gave a speech indicating that Saddam Hussein in Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction, had terror connections, and that therefore a military intervention seemed necessary. About a month later the chairman of the UN weapon inspectors, Hans Blix, also gave a speech in the Security Council reporting about progress in their work and asking for more time to investigate. Even though the two men addressed the same issue in the same place and in front of the same audience (which thanks to television and video recording also included the general world public), these two speakers were not treated in the same way by the camera. The camera took a different position and filmed from a different point of view on those two occasions. Today we can review the videos and compare how Hans Blix and Colin Powell were presented to the viewers in two very different ways.

Hans Blix we can see was filmed from above and from his left side in semi-profile. This means that he is not facing the viewers, he is not in eye contact with the viewers and not at the same level, he is being observed and looked down upon in a literal sense. This is significant because the metaphorical sense of “being looked down upon” (i.e. to be seen as inferior, unimportant, disliked, or irrelevant) may very well follow, this may very well be the immediate, instinctively and culturally conditioned reaction of the audience. This “downgrading” point of view of the camera is not supporting, but detracting from any ethos the speaker may have had in advance and in the situation, he is being framed not as an authority but as a partial voice in a debate, almost like an outsider commenting on something to someone else, not as an important person directly addressing the viewer.

The people in the Council room next to Hans Blix and visible in the background in the actual picture framing do not seem to pay much attention to his speech, they are moving about, fiddling with papers, one of them bending over looking for something in his briefcase etc. There is no symmetry or balance or steady order to the picture, no stable support from the people around him, so this does not sum up to make Hans Blix seem competent and trustworthy, on the contrary the television viewers are likely to be influenced by the attitude of the non-attentive people next to Hans Blix. It is quite standard psychology (known from the clever practice of so many talk-shows and tv-programs that have a very positive studio audience in the picture and on the sound track) that we as viewers tend to share the attitudes and reactions of the co-viewers on the set. It is socially contagious – even when mediated on film, tv, video and other platforms – to see other people behaving like entertained or bored, grateful or outraged, excited or distracted.

Hans Blix himself does not seem eager to present his report in an elegant or rhetorically powerful way, he is not trying to face the camera but reads rather monotonously from his detailed and technical report. The camera stays on him most of the time in this distanced and down-looking way, only a few times the producer shifts to other rather random views. There is a glimpse of Colin Powell at one time, and he neither seems to be following Hans Blix’ presentation with any attention at all. As we shall see shortly, this sort of “reaction shot” (here it is rather a “no reaction shot”) is also likely to have an influence on how we come to perceive the speaker.

Even though this may now seem like a rather unfavorable treatment of Hans Blix by the camera, there is hardly any reason to suspect a conspiracy or conscious plan to make him appear small and unimportant. It is more likely that this recording was just normal procedure, the usual type of video documentation of negotiations and speeches in the Security Council at that time, and with the cameras placed in convenient, for the participants un-disturbing places. But then in contrast it appears as if the presentation by Colin Powell a few weeks earlier was much more carefully staged and directed to camera crews well instructed and eager to make him appear trustworthy and impressive.

Various sources indicate that Colin Powel and his crew went through considerable preparations in order to make his appearance in the Security Council as persuasive as possible. ”Powell engaged in extensive rehearsal for the speech, rearranging the furniture in one room so that it would more closely resemble the Security Council chamber” (Zarefsky). Colin Powell himself has later admitted that his presentation was designed to be as persuasive and impressive as possible, and that it seemed successful in that respect, even though it later turned out that there were no weapons of mass destruction to be found in Iraq and that the alleged evidence and intelligence sources were less than solid:

…at the time I gave the speech on Feb. 5, the president had already made this decision for military action. The dice had been tossed… The reason I went to the U.N. is because we needed now to put the case before the entire international community in a powerful way, and that’s what I did that day… And we had projectors and all sorts of technology to help us make the case. And that’s what I did… there was pretty good reaction to it for a few weeks. And then suddenly, the CIA started to let us know that the case was falling apart… So it was deeply troubling, and I think that it was a great intelligence failure on our part… (Colin Powell, quote in: Breslow)

Looking at the video from Colin Powell’s address to the Security Council on February 5th, 2003, it is immediately obvious that this is not a casual recording from a distant camera somewhere up above, but that the camera has been placed right in front of the speaker and at the level of eye height. Colin Powell is in focus, in the center, and framed much how news readers or hosts of programs are usually framed, head and shoulder, but here also with his gesturing hands visible, and a sign on the table saying “United States”. This point of view of the camera gives the speaker the opportunity to exercise the “parental gaze”, as we saw it in the case of Nixon, Angela Merkel, and the Danish Queen in her ceremonial New Year’s Eve address. It is a point of view for the camera and the television viewer that (everything equal) highly supports the status, credibility, seriousness, expressiveness and impact of the speaker.

Even if one does not take into account the sound of Colin Powell’s very authoritative, sonorous, and well-articulated voice, the seriousness of his message comes across visually from his posture, facial expressions, and insisting gestures. And in the background of Colin Powell we see a balanced arrangement of well-suited, serious looking men, who actually seem to be listening to him and to support him, they are part of his national team (even if we did not know that one of them was the director of the CIA, their stern appearance still add to the power of the speaker they were so obviously backing).

Hans Blix did not show audio-visual material to the Security Council and the camera, but Colin Powell’s in his long and elaborated address made rather extensive use of sound-recordings, and graphical and video material shown on a large digital screen – and this was reproduced by the broadcasting and recording cameras. The reliability and interpretation of this material has later been called into question, but it functioned nevertheless as part of the overall rhetorical aim and persuasiveness of the speech.

Colin Powell and his team was not the first American delegation to use visual material as part of their presentation in the Security Council. About 40 years earlier during the Cuban missile crisis, Adlai Stevenson very dramatically brought posters with aerial photos of alleged missile construction sites on Cuba into the room and demanded a “Yes or No” answer from the Soviet ambassador, and famously declared that he was ready to wait for the answer “…till Hell freezes over” (Zarefsky). This scene became well known around the world, and on photos and video footage of the incident one can see, that the American delegation was placed much in the same way as later Colin Powell and his team (even though filmed a bit from above). No doubt the famous performance of Adlai Stevenson served as an inspiration for the crew of spin-doctors around Colin Powell, and the point of view chosen for the main camera seem well planned.

When talking about how dangerous anthrax was even in very small dozes, Colin Powell held up a small vial in his hand and showed it to the camera and the Council. This was an illustration, a visualization, that was very acute and impressive, perhaps even scary. In itself, of course, it did not prove anything about what was in Iraq or not, but Colin Powell rhetorically managed to imply a lot by this exhibit – and it was perhaps by some seen as visual proof of Saddam Hussein’s evil intentions.

Another display was a somewhat rough graphical drawing of a truck, in a way it looks today like a rather childish construction of a toy truck on a digital screen. Besides some unclear photos and videos, various constructed (drawn, not recorded) images were shown in coordination with Colin Powell talking about possible mobile facilities for dangerous weapons in Iraq. Today it seems ridiculous, or at least rather weak, to try to support a political agenda of invasion with “evidence” of this sort. It was only by means of Colin Powell’s status and trustworthiness, his great ethos, as previously earned and as supported and enhanced in this situation by the camera’s point of view, that it became a rhetorically viable road to convince viewers around the world.

Reaction shots

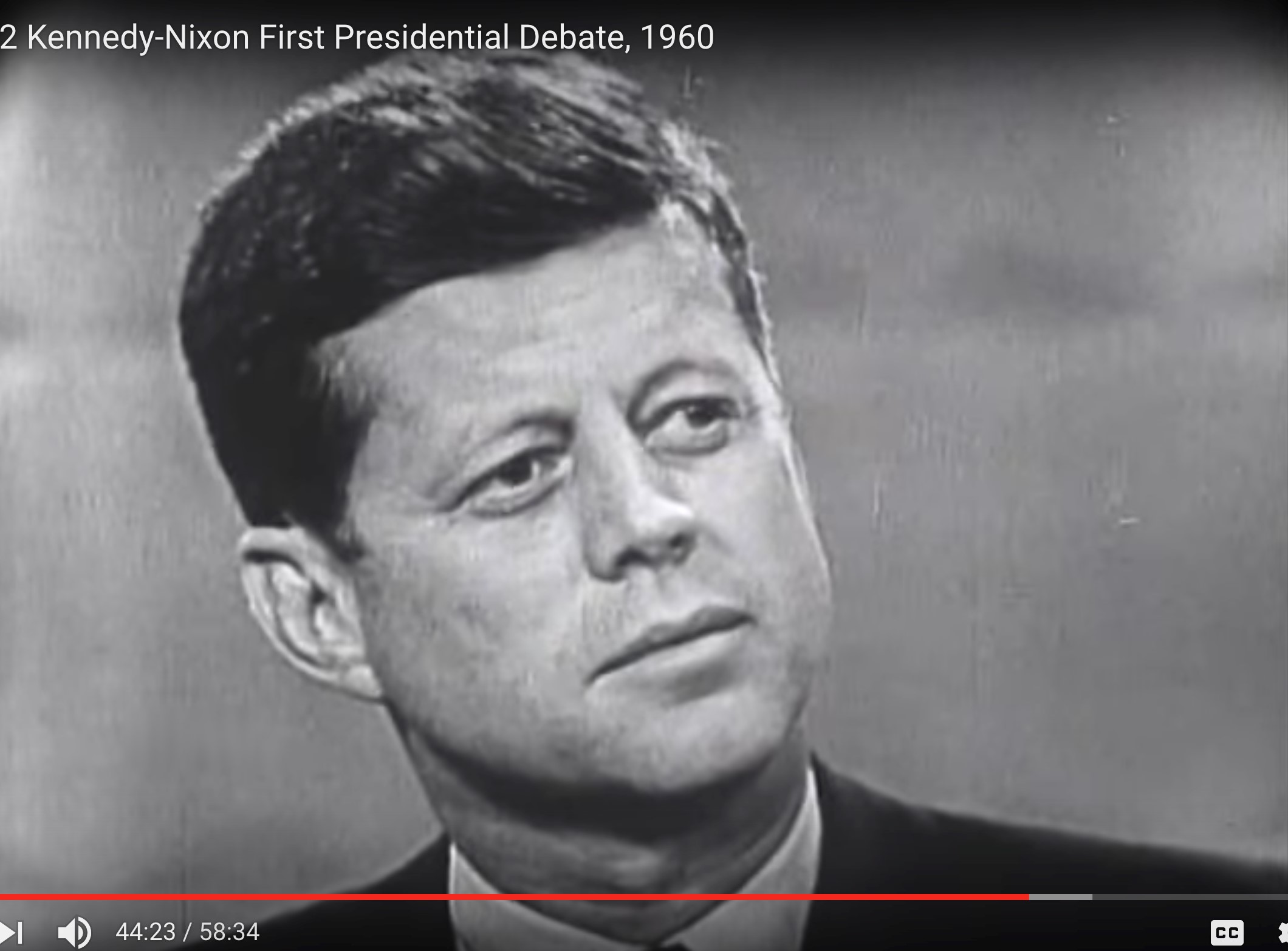

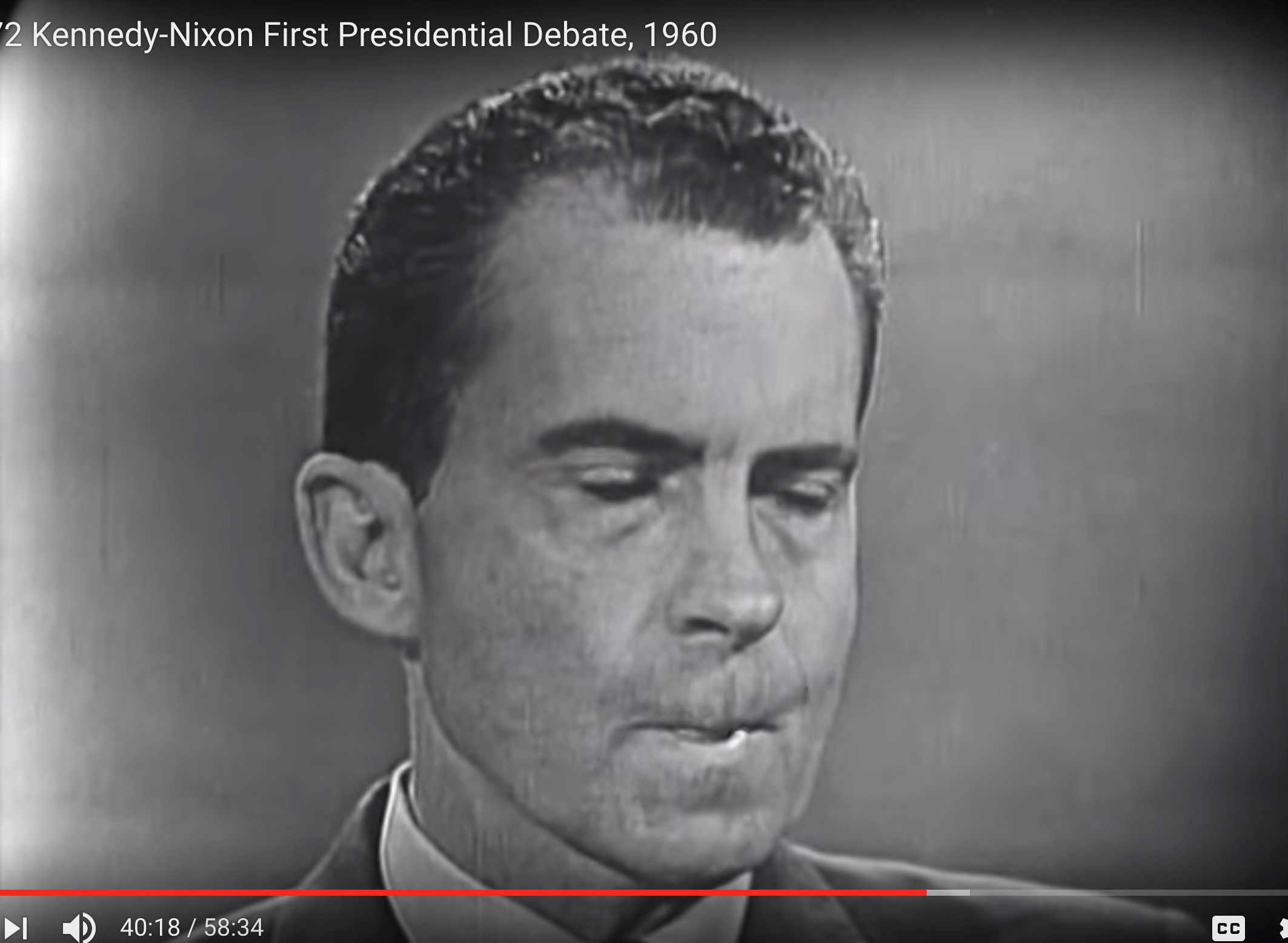

The debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon in 1960 up to the US presidential election has become renowned as the first live broadcast of a major political duel, and one that proved the new television medium to have a decisive influence. Even though it has later been questioned if the two polls were actually comparable, the story goes that television viewers favored Kennedy whereas radio listeners favored Nixon: “Television audiences thought Kennedy won the debate by a landslide, while radio audiences thought Nixon won it by a landslide” (Power).

Kennedy versus Nixon 1960 presidential election debate.

Reviewing the black-and-white footage confirms that Nixon does not appear quite as comfortable and stateman like as Kennedy. Nixon’s suit is grey, with little contrast to the greyish background, whereas Kennedy’s is black, making him look more distinct and authoritative. In the opening overview shot, which as mentioned is in line with film tradition and in line with what follows in many more television debates and speeches to come, we can see both candidates sitting in the chairs on either side of the debate host. Nixon sits in an awkward position with his legs crossed and seems nervous, Kennedy seems more relaxed and confident. This is perhaps not a huge difference, and certainly not one that can be ascribed to the camera work as both candidates appear in the same balanced (symmetrically framed) overview opening shot. Curiously enough the camera is a bit slanted to one side, not completely horizontal, but this seems to be just a small technical error, perhaps due to lack of studio routine.

Later, when the candidates in turn deliver their speeches on various points, the camera is closer (or zoomed in), with only one person appearing in the frame. Here both Nixon and Kennedy seem to perform quite well, they are framed in similar ways, and Nixon’s voice is actually very good and authoritative with no trace of nervousness. Perhaps it is worth considering also (to explain the suggested difference in audience reactions between radio and television) that Kennedy’s voice and rather high class New England accent may not have pleased all segments. So, when speaking and seen close up by the camera both candidates seem quite vigorous and confident. And the quality of this footage actually makes it hard to determine if Nixon was really sweating and unshaven, as it has often been claimed: “The cameras favored Kennedy who looked calm and composed throughout, while Nixon appeared unshaven and flustered” (BBC).

But even so, there is some truth in the claim that Nixon appeared as if unshaven and flustered. Because this is the impression the viewers get from the reaction shots or “listening shots”, namely the instances where the producer for a while shifts to the camera resting on the non-speaking candidate. Most of the time the speaking candidate is shown, but to make everything more lively, and quite in line with traditional film style, we once in a while see a shot of the listening person, so as to see his reaction or attitude towards what the opponent is saying. This shift of camera and attention is of course managed by the producer, but often it is quite unnoticed or natural for the viewer as it generally follows a question-answer, or action-reaction routine quite familiar to us, not just from film but as part of our culture, or perhaps it is even instinctively rooted in us.

During this early tv-transmitted debate Nixon is shown several times with a nervous face while not speaking, looking away from the other candidate and the whole scene, biting his lips, etc. It is during these reaction shots – and not while he is speaking himself – that Nixon appears rather uneasy and uncomfortable with the situation, and from there on one might perhaps also get the impression that he is sweating and unshaven even though the fairly poor picture resolution does not make such details distinctly visible. In contrast to Nixon, whenever Kennedy is shown close up while not speaking, Kennedy appears listening, attentive, alert, he is looking in the direction of his opponent and seems to lean into the debate, comfortable about being on stage and eager to contribute.

We are quite accustomed to see close ups of persons in video and film – and as early as during the silent area of film it has been noticed by film theorists that the audience tend to interpret and react rather strongly to the inferred “inner” sentiments of the faces portrayed, also when not speaking (Balazs, 1924). Also more recent film theorist have talked about Emotional contagion responses to narrative fiction film (Coplan, 2006) and about The scene of empathy and the human face on film (Plantinga, 1999).

Furthermore, even before the age of television and close up shots and reaction shots it was of course well known – at least to rhetoricians and political advisers – that the overall appearance of a politician does matter in the eyes and minds of the voters, and that this includes gesture, posture, haircut, clothing and behavior even when not speaking or being directly on a podium. In rhetorical terms the ethos of the speaker is inferred also from the non-verbal communication and appearance. So the rhetorical importance of this is not new, but what is new with the film media, television and video, is that the camera (the camera operators and the producers and editors shifting between different camera views) have the power to show or not show (and when to show, and how to show) different views of politicians on stage and in the middle of a debate. With the camera work a new layer of rhetoric can be said to be installed on top of the politicians own performance, and this rhetoric, these choices about what the audience will be allowed to see and not see, are in some cases, especially if not well considered and foreseen, pretty much out of the hands of the politicians themselves, their speech writers and their advisers. But, as we saw in the case of Colin Powell, the politicians and their crew may try to calculate and influence just how the camera work will be presenting the speaker.

When Bill Clinton ran against George H. W. Bush in 1992, the campaigners were aware of the importance of “video-bites” and “sound-bites”. Paul Beluga, a senior strategist in Clinton’s camp explained: “The key is: dominate the moment – that can then be put on the morning shows, the evening news, recycled” (Beluga). At one time, during the second of the three television debates between Clinton, Bush and the independent Ross Perot, the camera caught Bush looking at his watch while waiting for his turn to speak again. This was seen as a very unlucky move as it suggested that Bush felt uneasy and eager to get the debate over with.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6sUGKAm2YQ&t=3826s

An even more striking moment or video-bite appears a little later in the debate when a camera and the producer catches Bush sitting with a flabbergasted, sheepish looking face listening to Clinton. Bush had had some difficulty answering a critical question from a female voter in the studio, he had somewhat frowned and leaned away from the questioning, whereas Clinton in his turn approached the voter and seemed to answer her in a very personal way, friendly and eloquent. The cameras had been following Clinton’s tour de force closely from several angels, showing him amidst the voters in the studio, when all of a sudden we see a shot of Bush sitting in the background with a stupefied face, as if he felt hopelessly beaten by Clinton at that moment. A few shots later we see the camera moving a bit around the candidates, obviously trying to have within the same frame both the speaking Clinton in the foreground and the skulking Bush in the background.

Certainly in 1992 the camera people and producers were aware of what would be “good shots”, especially good reaction shots, but there is no reason to believe that they on purpose tried to favor one candidate over the others. However, even today, when shown to students at Roskilde University in Denmark (the author of this paper has tested this a number of times), this scene, with Bush appearing baffled in a reaction shot, creates immediate amusement, and the students find the Bush-figure ridiculous and beaten, even though they do not have many preconceptions about the debate or about the actual outcome of the election. So, reaction shots do seem to have an impact.

Even though the importance of camera work in relation to politicians seems to be generally underestimated (one exception being Grabe & Bucy, 2009), and though it seems difficult to keep track of the many ways in which it can influence the appearance of the politicians, there are examples of politicians who handle the challenges well and try to take back some of the control, e.g. by carefully staging their own appearance and being aware of the possibility of reaction shots and close ups even when not speaking.

One example is the Danish Prime minister Helle Thorning Schmidt’s reactions to a vehement verbal attack in the European Parliament in January 2012. Denmark held the chair at that time and after Helle Thorning Schmidt’s opening speech the Danish MP Morten Messerschmidt delivered a rather flamboyant and radical critique of her (and of the European Union in general). One could have expected the Prime minister to have reacted with attentive disapproval, perhaps even anger, or taking notes for a reply. However, we see something else in the three reactions shots of her during the three minute long critical speech by Messerschmidt: in the first shot she looks up and around smiling indulgently, almost as if speaker was just a remarkably naughty child and not a serious political opponent, in the next shot she seems not to be listening at all but to look at some of her own papers, and in the third reaction shot she is tapping/texting on what seems to be her smartphone. Clearly she demonstrates to the camera, in case it should film her, that she does not find the speaker worthy of any attention.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CB063m9aF-g&t=109s

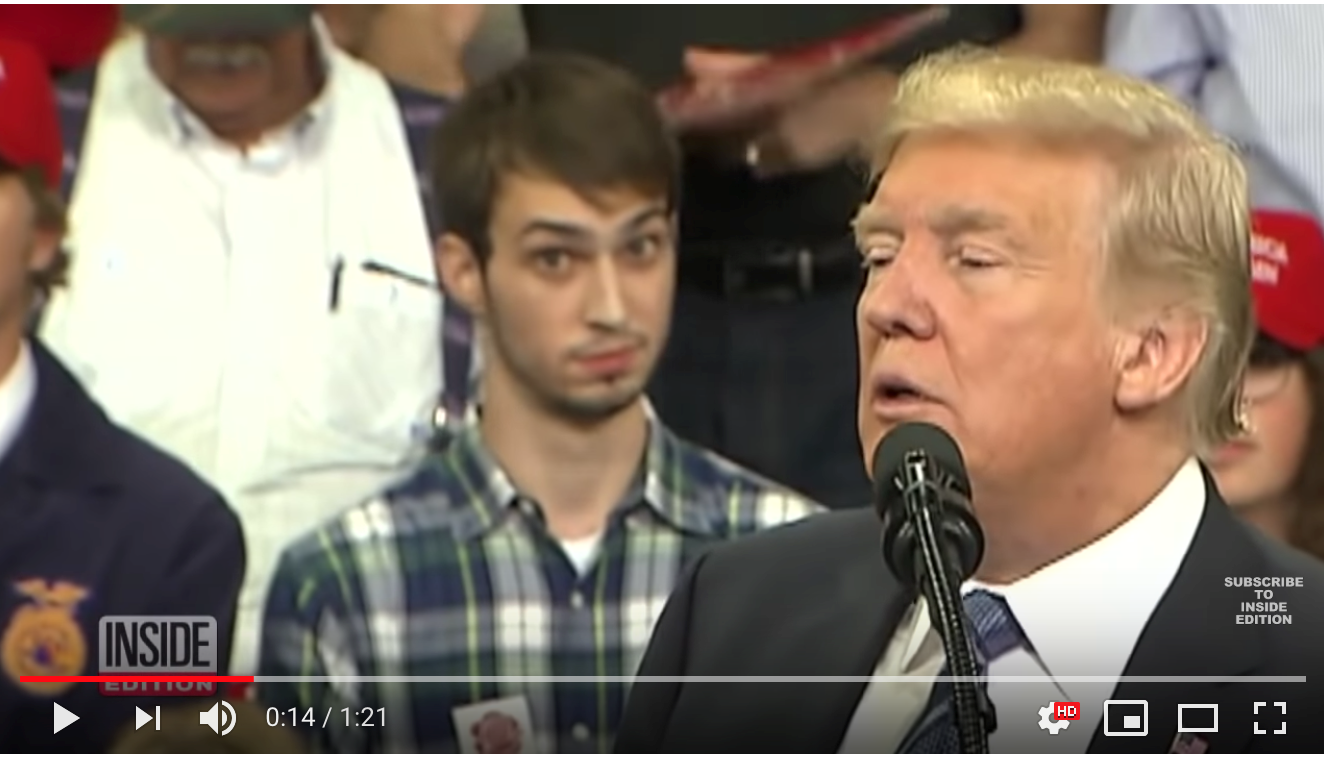

Again, in this example the camera work was in line with normal procedure and professional standards, no reason to suspect partiality here, and generally it may also be hard to say what the “right” or best balanced or unbiased camera work would be once and for all. But this recording – with its flamboyant speaker and the reaction shots of the undisturbed Prime minister – was shown on Danish National TV at the time, and it must be fair to assume that these reaction shots were significant to the rhetorical impact of the speech. A more recent and remarkable example of “reactions” caught (in this case involuntarily) by the camera is the video known as “Plaid Shirt Guy” from a Donald Trump rally in Montana, 2018.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4pcZdJcpbs

Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the rhetorical potential of various forms of camera work such as zoom in/zoom out, point of view, and reaction shots. Though these forms of camera work are quite often involved in presentations of politicians and political debates on modern media, the specific impact on the viewing audience has rarely been noticed or discussed in public and academic circles. With this paper the author hopes to contribute to a vital and critical phenomenological and rhetorical discussion of how politicians appear in today’s era of visual culture and digital media.

References

Balázs, Béla: Der sichtbare Mensch oder die Kultur des Films. Deutsch-Österreichischer Verlag, Wien u. a. 1924.

BBC: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-11792637/1960-nixon-v-kennedy

Beluga, Paul: Interview comment in: Race for the White House, Bill Clinton Vs George H. W. Bush, CNN nr. 6, April 10, 2016 (29:40) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CtXNaCAtiH8

Bordwell, David: “Classical Hollywood Cinema: Narrational Principles and Procedures” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology – A Film Theory Reader, (ed.) Philip Rosen, 1986. “Classical Hollywood.

Breslow, Jason M: Pbs. Frontline, May 17, 2016 http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/colin-powell-u-n-speech-was-a-great-intelligence-failure/

Coplan, A. (2006), “Catching characters’ emotions: Emotional contagion responses to narrative fiction film”, Film Studies, 8: summer, pp. 26-38.

Forbes, Hill: ”Conventional Wisdom – Traditional Form – The President’s Message of November 3”, 1969 in The Quarterly Journal of Speech, December 1972, Vol. 58, Number 4.

Grabe, Maria Elizabeth & Bucy, Erik Page: Image Bite Politics: News and the Visual Framing of Elections (Series in Political Psychology) (Kindle Locations 247-256) (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 344 pp.)

Juel, Henrik: The Ethos and the Framing, 2004, http://www.henrikjuel.dk/

Juel, Henrik: Communicative Functions, 2013, http://www.henrikjuel.dk/

Plantinga, C. (1999): ‘The scene of empathy and the human face on film’, in Plantinga, C. and Smith, G.M. (ed.), Passionate Views: Film, Cognition, and Emotion, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 239-256.

Power, Max: Comment 2008 to video clip on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QazmVHAO0os

Zarefsky, David: “Making the Case for War: Colin Powell at the United Nations”

Rhetoric and Public Affairs.Vol. 10, No. 2, Special Issue on Rhetoric and the War in Iraq (Summer 2007), pp. 275-302, published by: Michigan State University Press.