In the last two decades the immigrant population has increased greatly in Iceland (Statistics Iceland, 2020a). Immigrants come mainly from Europe and Scandinavia. Recently, due to the war in Syria, Iceland has experienced an influx of refugees from the Arab world. The most visible symbol of these new arrivals is seeing women wearing headscarves (Hijab) in Iceland.

There are cultural challenges involved in moving from an Arab country to Iceland, particularly because many Arab countries limit the participation of women in decision-making in almost all public and private aspects of life (Valentine, 2004). Arab Muslim societies are mostly considered to be patriarchal cultures, in which men have power over women (ibid.). Moving from this culture to Iceland, which prides itself as a leading country for gender equality, creates challenges.

The present study explores the perceptions and experiences of Arab Muslim immigrant women in Iceland. At this time only one MA-thesis has been done on the self-image of Muslim women in Iceland (Guðmundsdóttir, 2012), which focuses on their relationship towards Islam. The intention of this research is to gain more insights into the Arab Muslim immigrant women’s post-immigration experiences, the social and cultural challenges they face in Iceland and how they deal with conflicting norms and values between home and host society.

Background, theoretical framework and literature review

In recent years Iceland has experienced a growing number of Arab immigrants. In 2010 Iceland was home to 342 Arabs, up to 430 in 2015 and 833 in 2018 (Statistics Iceland, 2020b). The majority of Arabs in Iceland in 2018 were from Syria, with 217 individuals, and 215 from Morocco. From the total number of Arab immigrants, 279 are female and 554 are male. Compared to the Scandinavian countries, the Muslim community in Iceland is small (Seddeeq, 2017). The participants in this study are either refugees or women who immigrated to Iceland with their families.

Immigrating to a new country is a challenge for every immigrant (Kim, 2017), but the experience of immigration to a new country varies between individuals. Each immigrant has his/her unique immigration story. In general, when people immigrate to a new country, they bring with them their social and cultural capital, which encompasses their language, skills, education, behaviour, habits, traditions and experiences (Erel, 2010). Thus, when immigrants try to adjust to a different social and cultural environment, acculturation may occur (Berry, 2005). Acculturation is defined as “the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members” (ibid.: 698). Moreover, the acculturation process is related to two basic issues which challenge individuals and groups (ibid.). The first issue is the extent to which one can maintain one’s heritage, culture and identity, while the second is the proportion of contact and participation in the host society and with other ethnic cultural groups (ibid.).

When ethnic immigrants like Arab Muslim women move to a new environment like Iceland, many of them face cultural clashes between their own and the new culture. One of the options for Arab Muslim women to confront these cultural challenges is to use acculturation strategies by selecting and adopting cultural values and traditions from both cultures. In Norway, which is culturally similar to Iceland, Predelli (2004) describes how immigrant Muslim women in Oslo use the flexibility and complexity of Islam to define gender roles and to support their own views and practices like getting jobs or getting help in their homes.

The effect of the new society’s values on Arab Muslim women and families varies from one individual to the next, depending upon different factors such as religiosity, the effect of their own culture and traditions, education and class. Immigrants who live in an environment with a strong emphasis on tradition can find it more difficult to change their roles and values, while those with a more open mind may find it easier to accept these changes (Erel, 2009). In addition, the adaptation process for Arab Muslim women in the new society is affected by how flexible they are and by how the host society treats them (Barkdull et al., 2011; Kim, 2001). In his study on immigrant women from Turkey living in Germany and Britain, Erel (2010) discovered that if immigrants were flexible and able to change their cultural capital, the integration process was facilitated, even if it was difficult for these women to adapt completely to the new culture.

Being a minority group surrounded by a different culture with its values, traditions and beliefs leads immigrants to reassess themselves and their identity (Duderija, 2007). The development of a new identity for a Muslim Arab is closely dependent on his/her primary religious-cultural identity. There is a tendency for immigrants belonging to minority religious groups to become more religious after leaving their countries. For many Muslim immigrants in western societies, religion is considered to be an important component of their identity because it helps them to feel in control, and gives them a sense of belonging while living in western culture (ibid.).

In western societies, Muslim women wearing Islamic outfits are easily recognised. This visibility adds another challenge to adaptation. Arab Muslim immigrant women are the group of “others” because of their appearance. Studies have shown that the migration process may lead to isolation and the feeling of loneliness (Bereza, 2010; Ísberg, 2010). It is common that immigrant women feel isolated and culturally homeless when they move to a different social and cultural environment where they have less access to social life and less support (Bereza, 2010; Ísberg, 2010).

Methodology

This research focuses on the social and cultural changes and challenges faced by Arab Muslim immigrant women in Iceland. The aim is to gain a deeper understanding of the women’s post-immigration experiences and to map the experiences of Arab Muslim immigrant women who live in Iceland outside the capital area; their main social and cultural challenges, which are related to life changes, religion and cultural identity, differences between Iceland and the Arab world, adaptation, future expectations and how they experience the attitudes of the locals.

To answer these questions, a qualitative research method was used. As Creswell (2009) states, qualitative research is an adequate method used as a “means (of) exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups ascribe to a social or human problem” (p. 4). While doing qualitative research and during data collection, the researcher uses what he sees, hears and notices; it helps him to develop new concepts, to analyse the data, and to answer and justify the research questions (Patton, 2002).

The method applied consisted of semi-structured in-depth interviews with nine Arab Muslim immigrant women who live in Iceland outside the capital area for one to four years. The women were of three different nationalities. The age of the women ranged from 18 to 70 years old, and they had all lived in Arab countries for more than 15 years before moving to Iceland. By using semi structured interviews, the researcher is able to use a set of core questions in all interviews, but the structure is not set in stone; it is also possible to add questions or explore some topics in more detail or follow a new thread that the interviewee introduces.

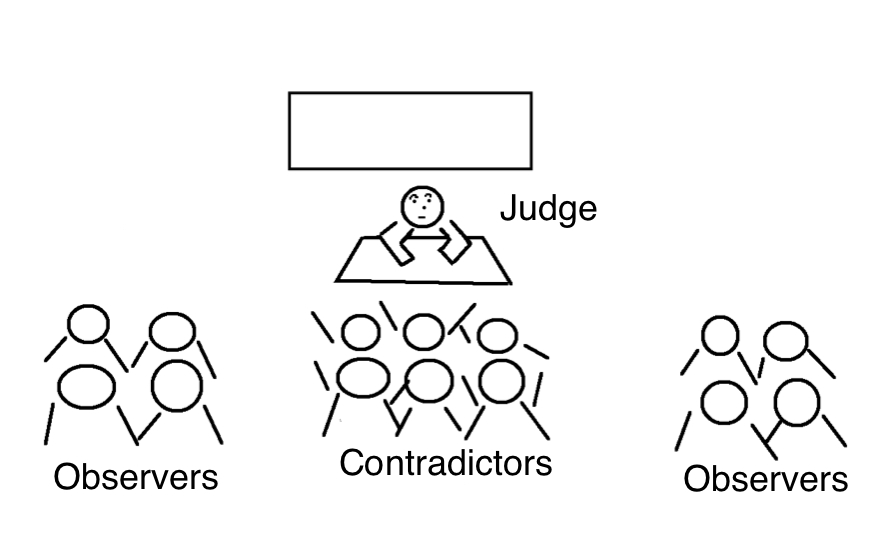

The data was analysed and interpreted by using the grounding theory approach tools. The grounded theory method uses a very systematic and structured strategy to analyse the data, which helps to delve deeper into the interviews materials and elicit meanings from the data (Woods et al., 2002). The grounded theory process is based on three coding steps: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. These three steps help break the original data down and clarify and arrange the concepts (Woods et al., 2002; Lawrence & Tar, 2013).

The participants grew up in different environments; three of them lived in developed cities. while the others lived in rural areas where it was not common for girls to go to school. Three of the participants do not read or write, four had only finished elementary school, while two are studying in secondary schools in Iceland. All but one wore headscarves.

Issues of confidentiality were raised at the beginning of the interviews and the participants were briefed about the research. At the beginning of each interview, the aim of the study was explained and permission to record the interview was given. The duration of each interview varied from 40 minutes to one hour. The location and the time of the interviews were chosen by the interviewees. They were carried out in Arabic. They were transcribed in Arabic and then translated into English. All the transcriptions were reviewed and analysed to bring out categories that related to participants’ experiences and attitudes, and themes were identified and explored in the following sections.

Data analysis procedures

Grounded theory is a systematic approach that helps the researcher to analyse the data through three steps. The first step started during and after each interview by writing notes and comments. The second step was coding the data. The coding includes three steps to find the core categories: open coding, axial coding and selective coding. In the grounded theory approach, you can use more than one coding at the same time. First, the interviews were read carefully and analysed line-by-line. Many codes that reflected the main concepts were created. This is called open coding. By doing this step the codes and concepts that were the basic units of analysis were discovered from the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Before going deeper into the codes, the codes were given similar labels to outline the primary categories for the analysis (Crang & Cook, 1995). Fourteen categories were found and labelled according to the aim of the research; lifestyle changes, social life, following their country’s traditions that the participants brought with them, culture shock, adaptation, language barrier, cultural and social differences, religion, dress code, gender roles, reactions of the host society, expectation vs reality, children’s happiness, children’s future prospects and educational approach in Iceland.

Secondly, the concepts and the codes discovered in the first step were connected, this step is called axial coding. Axial coding helps to find the connection between the codes, the concepts and the categories since “the use of the grounded theory approach allows the connection of codes and categories in the data to be established and theoretical propositions to be developed” (Woods et al., 2002: 46). The categories were combined and reduced to six sub-categories. These sub-categories were: lifestyle changes and traditions, differences and adaptation, isolation and social life, gender roles, religious identity and children’s school.

The third step was to select the codes and concepts which were related to the research aim and this stage of coding was the final step of coding and is called selective coding. Selective coding identifies categories that build the framework (Woods et al., 2002). This third step identified five categories which were labelled: life in Iceland, adaptation and lifestyle changes, social and cultural values, cultural and religious identity and children’s schooling and future expectations.

Ethical issues related to the study

All participants were willing to take part in this study voluntarily and gave informed consent. Before each interview, the purpose of the study and the benefits that would come from it were explained (Akaranga & Makau, 2016). Issues of anonymity and confidentiality were raised at the beginning of all interviews. To increase confidentiality, all personal information like real names, nationalities and ages, the name of the cities where the women live were removed. All women were given pseudo names in the findings chapter for confidential reasons. These names are: Aya, Fatima, Hanan, Hiba, Lubna, Maryam, Marah, Qamar and Zena.

Findings

The main findings are discussed in four main themes. The first theme explores the purpose behind migration and explains the challenges faced by the women; the second theme explores adaptation and lifestyle changes, the third discusses gender roles and values and the fourth theme is concerned with the women’s religious and cultural identity. These themes are all interconnected and highlight issues that affect Arab Muslim immigrant women’s lives in Iceland.

Life in Iceland and its challenges

The women have different stories behind their immigration to Iceland. Nevertheless, most of them implied in the interviews that they came to Iceland involuntarily. Marah and Fatima immigrated to Iceland because their husbands were already living there. For the refugee women in the study, the decision to move was mostly for safety and a better future for themselves and their children, since they had all left their native countries because of war. The opportunity to come to Iceland was arranged through the UNHCR resettlement program which does not give refugees the opportunity to choose the country of resettlement and leaves refugees without much agency in the decision process (UNHCR, 2018). Aya was the only woman who came to Iceland by choice.

The women’s first impression of Iceland was a shock due to the different environment and culture, and the distorted image they had of life in the country. Maryam had built up her ideas about Icelandic culture through Western media and movies. When Maryam came to Iceland she was surprised that “people in Iceland are respectful and they (Icelanders) wear conservative clothing”. She thought that “in Europe” she “would see naked people” and “people kiss or hug each other in the street” but was “totally wrong”.

Most of the participants had very little knowledge about Iceland before they immigrated. All the women agreed that when they tried to look for information about Iceland, the cold weather was the first occurrence they read about. The first image they had was of a very cold snowy country. Hiba was laughing when she explained that she thought she was going to live in a “freezer”. Lubna shared her experience: “We looked for information about Iceland on the internet because we didn’t know anyone living there, but the biggest difference was the weather. There was too much snow when we arrived. It is colder than we had expected, and the darkness and the daylight were different to what we were used to. I found it difficult in summer to see only the light, I like the darkness more.”

Socio-cultural challenges

The findings showed that most women experienced socio-cultural challenges when they first came to Iceland, because of the differences between the two countries. Lubna explained: “Men and women here like to hug and kiss and shake hands, which is unacceptable in my culture. Also, I was shocked when I went to the swimming pool for the first time. Women there take a shower near each other and without any clothes on. They don’t even try to cover themselves.” Zena also talked about cultural differences: “I am always afraid about my daughter, I don’t want her to have any sexual relationship outside marriage, it is shameful and forbidden in our culture. I am not afraid about my boys simply because they are boys and that makes them different.”

Aya grew up in a traditional Arabic society but her family was “open-minded” and gave her a lot of freedom. She could have friends of both genders even though that was not common in her society, however, she also experienced a culture shock in Iceland, when she met transgender people for the first time. She admitted that she was avoiding contact with them as much as possible. Aya was confused about the way to interact with them because it was something she had never experienced before moving to Iceland.

Language was one of the main obstacles in the participants’ lives in Iceland, since they found Icelandic very difficult and complicated. Still, the women agreed that learning Icelandic was important for their integration because it would build bridges between them and the Icelandic society. The findings indicate that learning the language was even more challenging for illiterate women. Zena was quite “happy” learning Icelandic but being unable to read and write made it more “difficult” and it might take her a “longer time” to be able to speak it. Fatima stated that Icelandic was “very difficult” and she was “not sure” if she would learn it.

Due to the lack of language skills the participants had trouble communicating with others, particularly professionals and institutions. They found it very hard to express themselves without a translator. Being unable to communicate and express their feelings and needs led to anxiety when they first arrived in Iceland. Hiba said: “Language is the most difficult challenge for me. It is hard and new, and because I don’t speak any other language like English I always need a translator when I go to doctors or to the bank or to my children’s school.”

Even the women who had been living in Iceland for a longer time still considered language as one of the biggest challenges. Marah expressed her disappointment at not being able to communicate without a translator: „Language was and still is the biggest challenge for me. It is very difficult and because I don’t speak English I always need someone to translate for me (sigh).” Like Marah and Hiba, Lubna was frustrated about how complicated she thought Icelandic was. She added that people did not understand her because of her “different accent”. In a similar way, Qamar was aware of the difficulty of the Icelandic language but she was also aware of the importance of the language in order to build her future, continue studying or find a good job. Qamar missed communication with her classmates and other people because she did not “speak Icelandic or English”. Consequently, she felt lonely and isolated.

Loneliness and isolation

The other participants felt lonely and isolated too. The lack of language proficiency, which creates communication difficulties, isolated the women to some extent from the local community. All the participants came from a cultural background where they had strong family ties. The extended family lived in the same area and they visited each other frequently. They also had a very active social life within their neighbourhoods. All the women had in common that they missed the social life they used to have back in their countries. Hiba explained: “I have a nice home here and my life is better but I am bored and I feel lonely here, I am sitting at home almost the whole day. I used to go out and see my friends and meet my family almost every day.” Zena’s story is similar: “My life has changed since I left my country […] I am sitting at home almost the whole day. I used to go out and see my friends and meet my family.”

It is common among immigrants who come from very different ethnic groups to attempt to keep the connections to their culture of origin in order to decrease the feeling of homesickness and loneliness. Two factors were important in the participants’ immigration experience: ability and flexibility. For example, Hanan, the oldest woman in the group, did not find it hard to adapt to the Icelandic society. Hanan was flexible and open to the Icelandic culture. She was grateful, “happy and satisfied” to be in Iceland. Even though she experienced many social and cultural barriers to be accepted and welcomed in Icelandic society, it was enough for her to feel “stable and secure”. The biggest obstacle for Hanan was being far from her family but she dealt with that by communicating almost every day using social media.

Marah had a different experience. She felt that adaptation was very hard and slow because she wore a headscarf and was worried about people’s reactions. After Marah first came to Iceland she “preferred to stay at home and never go out”, because of her Islamic outfit. She was depressed and withdrawn for a long time. Marah was isolated until she made a personal decision to “integrate more into the society by learning Icelandic”. When she started to learn the language, she felt more confident and she decided to find a job to communicate more with people. Marah was very stressed in her first days at work, worrying about communication and she was afraid that people might not accept her headscarf. However, she mentioned that everyone was willing to help her and that no one bothered her because of her headscarf. She was happy at work and continued to learn the language.

Qamar’s experience was similar, she found it hard to adapt because of her headscarf. She noted that learning the language was the key to adapting to the Icelandic society. Qamar was one of the refugee women who started to learn the language soon after she arrived. She participated in an organised program for refugees which included learning the language and some aspects of Icelandic culture. Getting to know the Icelandic society helped the women and was an important part of their adaptation process.

Arab Muslim immigrant women in this research described very different cultural and religious backgrounds which affected their adaptation processes. The women who came from very conservative families found it harder to adapt than the women who came from more liberal families. Aya had no problem shaking hands with men or even friendly hugs. Hiba’s experience was very different, she felt “guilty” when she had to shake hands with men, but she was too shy to tell them that in her society people do not shake hands with the opposite sex. In her country, the opposite sexes greet each other by leaving a space between them and putting their right hand over their heart. Likewise, Lubna claimed that she was unhappy that men and women sat together when they visited each other because, in her country, men and women would be seated in different rooms.

The interviews reflected that all the participants experienced positive and negative transfers in their lives after they immigrated to Iceland. Some of the changes in the participants’ lives helped their adaptation processes. For example, for Maryam, Lubna and Marah, working was a big transformation in their lives; they used it to meet people and learn about the Icelandic culture and also to learn the language, which they considered as the key to understanding the social structures.

The findings indicate that the most obvious changes in the women’s lives occurred in their lifestyle and personality. One of the women thought that she had a “more organised life”. In her opinion, she had started to think like Icelanders who “have time organised for everything; for work, food, family, study, and holidays. They work during the winter and travel in the summer”. Another woman said that she is more “responsible” than she used to be in her country. She has learned how to “respect and deal with people”.

The women feel that living in Iceland gave them more control over their own lives. Seven of the women said they used to spend most of their time in their home country caring about the family and its needs. After moving to Iceland, they were able to do more for themselves and “not only for the family”, like learning the language and having a job. This was a big change for them and they said they were more satisfied and confident and trying to be independent, even though the majority of them agreed that their roles within the home would not change.

Maryam, who had already found a job, expressed her feelings by saying: “I have a job and I feel that I am doing something for myself not only for my family, I am also learning Icelandic. I feel more confident and appreciated.” Similarly, Lubna’s lifestyle has changed. She “used to stay at home most of the time” caring for the children and doing housework. Going out alone was not possible for her and “her husband always had to be with her if she wanted to go out”. After she moved to Iceland, she was very happy that her life is “totally different”. Lubna said that in Iceland she is a “stronger woman”. She is “looking for a job, goes shopping alone sometimes, takes her children alone for a walk”. She also added that “the women who work or study are more appreciated and responsible”. Lubna’s husband supports and “encourages” her “to study and work which was impossible” in her country because of the traditions which made women feel “guilty” if they decided to get a job.

The support of the husbands played an important role in the acceptance and adaptation to the Icelandic lifestyle. Marah’s husband “helped and supported” her “a lot” to adapt to her different Islamic dress. He also helped her to understand the different lifestyle and gender role values in Iceland. Marah explained how her life is different in Iceland by saying: “My lifestyle has changed a lot. There were many things I couldn’t do in my country but here I can, like driving and learning another language. Now I am studying. It is just different here.”

Gender roles and values

The women all experienced differences in gender roles from their home countries. According to the women in this study, traditionally women have fewer rights in their countries, for example in education, work and choice of a husband. The women explained that girls have limited freedom in their countries and parents restrict girls’ social life because girls are special and have different roles. Five of the women did not go to school or stopped studying because of traditions which consider girls as a source of honour that has to be protected by their families. As Hiba described: “I studied only to 6th grade because it is thought that it is better for girls to stay at home and marry early. Only boys can continue studying and go to university.”

The women pointed out that in Arab societies men and women have different responsibilities. The women’s priority is inside the homes, doing housework and raising children while men are obliged to take care of the household expenses. As Hanan explained: “it is shameful for men to help with any housework […] In Iceland men clean and cook and wash the dishes. In addition, women are often financially independent.” Similarly, Zena explained the responsibilities of men and women in her country: “Men’s responsibilities are to go and have a job and make money while women’s responsibilities are inside her home, doing housework and caring for the children. Even if a woman has a job, it doesn’t give her the right to ask for help in cleaning or cooking but if a man helps her that means that he is a very good man.”

The findings indicate that women who are married to Arab men who have lived for a long time in Europe have different experiences from the women who are married to men who have always lived in Arab countries. Marah said she was happy that all the responsibilities inside her home are shared between her and her husband because “he has been living in Europe for a long time, he knows about women’s rights”. He supported her integration by helping her with her Icelandic language homework.

On the other hand, Fatima’s husband, who has also lived in Europe for a long time, was different. When she first came to Iceland her husband was very helpful but after a while he “began behaving like a typical Arab man, giving orders, controlling” her life and limiting her freedom. She said: “My husband didn’t want me to go out or learn the language”.

The different gender roles in Iceland have positively influenced these women. Most of the women participating in this study have tried to adopt new roles at the same time as accepting their traditional responsibilities. Fatima explains: “The way of thinking is different. Men here (in Iceland) respect women and help them while in Arab countries they try to control them as much as they can.” This adoption could be comprehended in the common desire of most of these women to learn the language and to get jobs outside the home. Hence, most of the women believed that their responsibilities at home would not change even if they got a job and shared the household expenses. Lubna said: “Even if I had a job he (her husband) would not help me with cleaning or cooking. Arab men are not used to doing it and they would not.” The home is still a very private place, as exemplified by Luban: “if my husband does anything bad to me I will not complain or go to the police, and I will not ask for a divorce because this will affect my children and my family and my life, I am happy like this and I can deal with my problems inside my home.”

Cultural and religious identity

Religion plays an instrumental role in the lives of all the interviewees. Their religious identity is reflected in their commitment to religion: praying, fasting, reading and following the Holy Quran and the Islamic dress or hijab. Religion is also the foundation of their cultural identity and a way to maintain their traditions and lifestyle. This was clearly demonstrated in their responses when asked what specific cultural traditions they brought with them to Iceland. Lubna said: “My commitment to my religion, praying, fasting and reading the holy Quran.” Hiba agreed: “The most important things which are always with me and I bring here are my commitment to my religion, my prayers, reading the holy Quran, not shaking hands with men, and my Islamic outfit.”

As Muslim women, religious practices before immigration mostly occurred inside the home. However, the lack of an Islamic religious atmosphere outside the home made them feel that they do not belong. The absence of a religious atmosphere was a big concern for the women who were afraid of losing their identity. Zena found it strange not to hear the voice of the Adhan (the call to pray which is heard loudly five times a day in all Muslim countries), and she was very emotional when she said: “They don’t have a mosque […] I miss our religious atmosphere.”

In addition, being recognised as a Muslim woman was important to the participants after immigrating to Iceland. The Islamic outfit or headscarf which makes Muslim women visible is a very important part of the interviewees’ religious and cultural identity. Hiba describes: “My Islamic outfit is my identity and I am happy to wear it.”; Lubna said: “I am proud of my headscarf. It is only for me and I don’t like to be criticized because of it, but luckily here in Iceland people accept me as I am.”

The women in the study explained that Icelanders are very curious to know more about the Islamic outfit. Most other immigrants in Iceland are from Eastern Europe and they are not identifiable, whereas the Arab Muslim women wearing headscarves stand out. When asked about her feelings when they wear the Islamic outfit, Zena said: “When I am wearing my Islamic outfit I feel people are very curious about it, they want to understand why we wear it.” Some worried if they would be accepted, as Maryam explained: “I was afraid about how people in Iceland would treat me with my Islamic outfit. They are curious to know more about it, so they ask many questions and sometimes I feel they don’t believe that we have hair (laugh).”

Nevertheless, all of the women agreed that this curiosity about the headscarf makes them feel uneasy. All the participants faced either questions about their headscarves or uncomfortable looks, although these questions about the Hijab did not bother some of my interviewees. Hanan described: “My Hijab is part of me and people here respect it. Sometimes they ask me why I wear it or they want to see my hair. These kinds of questions don’t bother me and my answer is that this is my religion and God asks me to do it.”

On the other hand, the younger women were more sensitive to these kinds of questions or looks. They explained how young people have strange ideas about the Hijab. They said most Icelanders do respect and appreciate them as Muslim women, although a few of them do not, especially young people. For example, Qamar was not sure if people respected her Islamic outfit. She was very upset when she explained that one girl thought that she wore a headscarf because she did not have hair: “I am not sure if people respect my Islamic outfit. They tried to tell me that I would be more beautiful without it. Sometimes they ask strange questions like once a girl asked me if I have hair… can you imagine!!”

The one woman who chose not to wear the headscarf was challenged by her own community. Aya was a bit excluded and she explained that her relaxed dress code was taken as a sign of excessive freedom in other matters, especially by Arab men. She blamed the Arab traditions which make her be judged according to her appearance by saying:

I don’t wear a special costume like a headscarf or long tunic and that causes me to have troubles, not with Icelanders but with other Arab people who live here especially men. I feel that I don’t belong to the Arab community in any way. They judge me by my looks and my clothes and forget other things. This is the Arabic way of thinking, unfortunately.

When asked if they consider their Islamic dress as a barrier to accessing the facilities in Iceland, most women said it does not. They felt glad that they were respected as they are. In addition, they are all planning to have jobs and some already do. Fatima explained: “My religion is very important no matter where I am. I wear the headscarf and inside my home, I sometimes wear the traditional dress. I don’t consider my headscarf or dress as barriers to accessing the facilities in Iceland. People respect me as I am and do not judge my dress at all.”

Others described their experience as similar, except for one younger woman who thought her Islamic outfit was a barrier. Qamar felt that there would be people anywhere who did not understand her Islamic outfit and would need time to accept it. She said: “I consider my Islamic outfit as a barrier to accessing services, and not just in Iceland because people need time to accept and understand me, it might take time until they become used to my Islamic outfit.”

The findings revealed that all women have a common hope to preserve their culture and traditions for their children. The interviewees thought it is important to preserve their religious and cultural identities and this was obvious when they insisted on teaching their religion, culture and traditions to their children. Arab Muslim immigrant women’s traditions, norms and values are influenced by Islam, which is considered as a way of life for most of these women. The women preserved a strong sense of their own religious and cultural identity, but their identity was also changing by having jobs and learning the language which helps them to integrate more into the Icelandic society.

One of the important factors which help the participants maintain their religious and cultural identities was the supportive local community, especially for the refugee women. Before moving to Iceland some of the women felt stressed because they had so little information about the people in Iceland. These women were worried about the way they would be treated in Iceland because of their different cultures and special outfit. After they moved to Iceland, some of the women were surprised about how welcome they were, which made their adaptation process easier. Hiba explained: “Yes, I feel welcome, all Icelanders I have met have shown me respect and they are happy to have us here. They have helped us a lot since we arrived. In the same way, I also respect them and always try to show my best behaviour.” Other women described their experiences as being similar.

Discussion

The findings indicate that the immigration of Arab Muslim women to Iceland created a cultural conflict, which led to social and cultural challenges. Even though the different environment and the weather was the first shock for all the women in this study, the cultural shock has had more effect on the women’s lives and adaptation process in the long run. The findings showed that the women adopted two acculturation strategies: separation and integration. When it comes to Islam, the women chose to maintain their religion and said that Islam is the foundation of their lives. It plays a prominent role in their lives and it influences every aspect of their daily activities. The women adapted to the new society while keeping their commitment to their religion and celebrating their religious festivals. For some of them, religion is considered as a culture and tradition which they grew up with and which they feel a need to maintain and keep their commitment to and teach to the next generation. The women coped with their membership of a minority religious group by putting an extra effort into ensuring that their children kept their home country’s religion, traditions and beliefs. The women were dissatisfied with the unequal gender roles in their countries, while at the same time they maintained this gender regime, for example by being more relaxed about raising boys than girls.

The feeling of being unwelcomed and discriminated against based on their race make immigrant women feel isolated and disappointed (Kim, 2017). However, the women in the study all felt welcomed and appreciated in the Icelandic society. The supportive welcoming society made the women’s immigration experience more positive. Social networks in the new society play an important role in supporting immigrants and may reduce the loneliness and the trauma of family separation. These social support networks assist immigrants during their adaptation process to the new life in the new country (Kim, 2017). Still, the women in the study expressed a feeling of loneliness and some felt isolated.

Kim (2017) found that immigrants tend to have a special social connection with their ethnic group and in line with that all the women in this research have good connections with Arab society. Ethnic groups tend to keep their original identity as part of their ethnic community. In the host country, they meet to share, among others, language, music, food which they had in their culture and which may help to decrease the acculturation stress and the loneliness of the family separation (Kim, 2017). The relationships with the other women from the same ethnic group helped the participants mentally and emotionally when they needed help. Although strong relationships between the same ethnic group members help ethnic immigrants in their early adaptation, this may limit their integration and active involvement in the host society which can lead to more isolation after a while (Kim, 2001).

The women integrated into the Icelandic society by adjusting to some of its values and behaviours. Most of the women showed that they respected and accepted the new culture with a positive attitude and showed an interest in adapting to new values in Icelandic society like gender role values. This is in line with Perdelli’s (2004) findings from Norway where Arab Muslim immigrants use the flexibility of Islam to be employed outside the home and to get help from their male relatives. The participants in this study were empowered by the Icelandic gender roles values and most of the women had tried to find a job (some already had one) or were learning the language to become more integrated into the Icelandic society. Hence, they had faced many challenges and obstacles related to the different cultural values between the two societies.

Language is considered to be the key to the adaptation of immigrants. Learning the language is an effective way for immigrants to get to know the new culture with its beliefs, norms and values and to manage the daily activity in an effective way and deal with obstacles in the new society (Kim, 2001). By having a job or being able to speak Icelandic, the participants felt more appreciated and confident. Increasing the ability to interact with the locals using the host society language is one of the highest achievements for immigrants (Kim, 2001). All the women, except the oldest one, were aware of the importance of learning the language. Most of them were enrolled in Icelandic courses and some had private teachers to help them at home. Learning the language is important for immigrants, not only to build a bridge with the host society, but it is a sign of integration in the host society (Kim, 2001).

The participants introduced themselves as Arab Muslims. They shared a heightened sense of their cultural background. However, because of their immigration experience, the women faced a change in the construction of their identity. These women immigrated from countries where they belonged to a majority (religion and culture), while in Iceland they belong to a minority group. This relocation between the different societies produces new hybrid identities, often with religion as their foundation. Religion plays a significant role in the construction of the new identity for many immigrants especially when they are a minority religious group (Duderija, 2007).

The women’s new hybrid identity is a mix of their ethnic identity and the new values and behaviours that they are adopting in the new culture. The participants selected the Icelandic cultural values which suited their way of thinking as Arab Muslim women. However, the women were caught between the two cultures in some ways. None of the women felt fully integrated into Icelandic society, they chose to balance the two cultures and adapted themselves to the new environment while preserving their own cultural identity and background (Kim, 2010). They had different degrees of acceptance of the new Icelandic cultural values depending on their personal flexibility and the extent they wanted to keep or change their own cultural values. Some women had difficulty incorporating their own Arabic cultural values into Icelandic western cultural values. For example, shaking hands with the opposite gender was a problem for at least three women in this study, whereas others did not mention it at all.

The process of developing the new mixed identity is challenging for immigrants because of the importance of maintaining their religious identity (Berry, 2005; Bereza, 2010; Kim, 2010). The participants insisted on being identified as Muslim women outside the home by wearing their Islamic outfit. The women’s Islamic headscarf confirmed their Muslim identity and is a highly salient aspect of their religious identity (Guðmundsdóttir, 2012; Ólafsdóttir, 2017). Arab Muslim women who wear headscarves agreed that their Islamic headscarf was one of the biggest challenges they faced in Iceland outside the capital area. None of the women mentioned any kind of racism regarding their appearance. However, the women were challenged by the curiosity of people who wanted to know more about it. Identity construction is related to how the host society perceive immigrants and not only the way they introduce themselves (Eriksen, 2002; Ólafsdóttir, 2017). The women hoped that the Icelandic society would not judge them according to their appearance but would appreciate them for their personal qualities and behaviours.

Conclusion

The findings revealed that Arab Muslim immigrant women are generally doing well in Iceland. However, they need more time to integrate fully into Icelandic society. The study found that there are varieties of cultural and social barriers which make Arab Muslim immigrant women’s integration process slow. The different environment, cultural and social differences, the variety of cultural values like gender roles and childrearing values, language, dress code and children’s schooling and future are the main challenging factors faced by the women and cause some struggling to adjust to the Icelandic society.

The participants perceive themselves according to their ethnic identity. On one hand, the women admitted to some adaption to new western values and ways of thinking. They found themselves caught between the two different cultures struggling with different values and norms, which led to mixed identity to help them define accurately who they are and where they fit in. The women were not able to separate their religion from their ethnicity since religion plays a significant role in their lives. Life in the new country was organised around following and respecting Islamic teaching. This influenced the type of clothes worn, their ability to have communication with the opposite gender, to find a job and to control their family life inside and outside their home. On the other hand, the women were able to control and choose the values and behaviours which were not dictated by their Islamic roots and beliefs. In addition, the findings showed that the longer Arab Muslim immigrant women had lived in Iceland, the more they had become open to Icelandic values.

One of the important factors affecting and making the women’s immigration experience more positive is a supportive society. The locals’ positive attitudes towards the women, especially the refugee women, encourage them to integrate more into Icelandic society and to learn the language or find a job. Nevertheless, the lack of language skills limited the women’s social activities and interaction with the locals which caused a feeling of non-belonging. The findings suggest that learning the Icelandic language would lead Arab immigrant Muslim women to a better life and ease adaptation into the new society.

References

Akaranga S.I. & Makau B.K. (2016). Ethical Considerations and their Applications to Research: A Case of the University of Nairobi. Journal of Educational Policy and Entrepreneurial Research 3(12), 1–96.

Barkdull, C., Khaja, K., Queiro-Tajalli, I., Swart, A., Cunningham, D., & Dennis, S. (2011). Experiences of Muslims in four Western countries post—9/11. Affilia: Journal of Women & Social Work 26(2), 139–153.

Bereza, M. (2010). Immigrant adaptation and acculturation orientations. Unpublished BS dissertation. University of Iceland, Reykjavík.

Berry J.W. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29(6), 697–712.

Cook, I., & Crang, M. (1995). Doing ethnographies: Concepts and techniques in modern geography. Norwich: School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Duderija, A. (2007). Literature Review: Identity Construction in the Context of Being a Minority Immigrant Religion: The Case of Western-born Muslims. Immigrants & Minorities 25(2), 141–162.

Erel, U. (2009). Migrant women transforming citizenship: Life-stories from Britain and Germany. Routledge.

Erel, U. (2010). Migrating cultural capital: Bourdieu in migration studies. Sociology 44(4), 642–660.

Guðmundsdóttir, V.B. (2012). „Þetta er ekki bara hlýðni“. Sjálfsímyndarsköpun múslímakvenna. Unpublished MA dissertation. University of Iceland, Reykjavík.

Ísberg, R. N. (2010). Migration and Cultural Transmission: Making a Home in Iceland. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of London, London.

Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross‐cultural adaptation. Sage.

Kim, Y. Y. (2017). Cross-Cultural Adaptation. Communication. DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.21

Lawrence, J. & Tar, U. (2013). The use of grounded theory technique as a practical tool for qualitative data collection and analysis. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 11(1), 29–40.

Ólafsdóttir, H. (2017). Mitt val: Sjónarhorn múslimskra kvenna á aðlögun og notkun blæju í nýjum menningarheimum. Unpublished BA dissertation. University of Iceland, Reykjavík.

Patton, M.Q. (2002). Two Decades of Developments in Qualitative Inquiry: A Personal, Experiential Perspective. Qualitative Social Work 1(3), 261–283.

Predelli, L. N. (2004). Interpreting gender in Islam: A case study of immigrant Muslim women in Oslo, Norway. Gender and society 18(4), 473–493.

Seddeeq, A. H. (2017). Islam in Iceland. In Bilá, A. (Ed.), Muslims are: Challenging stereotypes, changing perceptions. Baštová: Nadácia otvorenej spoločnosti – Open Society Foundation.

Statistic Iceland. (2020a). Population. Retrieved from https://statice.is/statistics/population/inhabitants/background/

Statistic Iceland. (2020b). Population. Retrieved from https://px.hagstofa.is/pxen/pxweb/en/Ibuar/Ibuar__mannfjoldi__3_bakgrunnur__Faedingarland/MAN12103.px

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2018). ‘Refugees’ and ‘Migrants’ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/56e81c0d4.html

Valentine M., M. (2004). Towards Gender Equality in the Arab/Middle East Region: Islam, culture, and feminist activism. Human Development Report Office (HDRO), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/towards-gender-equality-arabmiddle-east-region

Woods, L., Priest, H., & Roberts P. (2002). An overview of three different approaches to the interpretation of qualitative data. Part 2: Practical illustrations. Nurse Researcher 10(1), 43–51.