In the midst of modern digital, social, and visual media communication it may seem out of place and out of date to look for guiding principles among ancient rhetoricians like Aristotle and Cicero: how could they possibly help today’s students cope with the challenges of modern communication? They do not seem to have written much about how to obtain “likes” or followers on social media. At least, not directly; however, they did write quite extensively about how to relate to an audience, how to adapt to a situation, how to appear trustworthy and convincing, how to make a point clear and memorable, and how to gain influence and defend oneself in the courtroom and in society. And they were quite aware that a good rhetorician had to keep an eye on changing conditions and contexts, and adapt to the situation. Perhaps some of their profound insights might even prove useful for coping with the political rhetoric on Twitter today. So, classical rhetoric may still be of some value to the modern student, not just providing critical and analytical academic tools for looking at the texts and performances of others in today’s media, but also inspiring active and personal skills in various upcoming genres of speech and oratory.

Speaking unmediated in front of a large audience at the town square—like Cicero at the Forum Romanum—now seems to be a very exceptional case. It is still possible to go to London, get up on a box and practice one’s rhetorical skills at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, and on Sundays there might even be a few sober passersby who will stop and listen for a while. I have myself, as part of my work at Roskilde University in Denmark, led a number of field trips to Speaker’s Corner and instructed many students about how to deal with this speaking challenge, and it has been quite a learning experience, but of course a little out of the ordinary (Juel, 2005; Carlsen & Juel, 2007, 2009) . However, more relevant for today’s students are be occasions like oral exams, paper presentations at a conference, defending a thesis, going to a job interview, presenting a project idea, chairing a meeting or a discussion within an organization, inspiring a cultural event, taking on ceremonial speeches within the family, pitching one’s own academic résumé in an elevator, or being interviewed as an expert on live TV about a subject within one’s own academic field. These are typical situations of today requiring rhetorical skills and competences in live speaking. But how, when, and where do the students of today learn about this? Writing essays and reports without ever practicing the use of voice and body, or how to pitch in live situations, is not the best way to prepare for this—nor the best way to turn students into active citizens in democratic societies. However, at most universities, guidelines on writing serve as the students’ main or only preparation for all genres of future rhetorical challenges.

In the following I shall argue for the relevance of teaching rhetorical actio (live performance) more directly and efficiently, and I want to encourage a phenomenological approach and point out the didactic benefits of a collaborative, corporeal, and visually oriented perspective on speech and oratory.

Orality makes a comeback

The development of modern media presents a potential overcoming of distances in time and space. We can now swiftly exchange messages and often even see and hear each other despite any physical distance. This actually means a sort of renaissance for live or almost-live face-to-face communication and orality. As early as 1982, Walter J. Ong remarked in his Orality and Literacy – The Technologizing of the Word that radio, television and telephone are technologies belonging to “the age of secondary orality” (Ong, 2002:167). Traditional norms and forms of writing culture are challenged: the short phrases of oral speech and everyday conversations leave their mark on digital messages such as political comments on Twitter; mimics and gestures pop up as icons, smileys and emoticons; the presence and dynamics of the personal meeting are mimicked by the camera movements and montage of filmic media (video and television, digital games and virtual reality).

Within the Western (if not global) educational and academic world, however, the norms of literacy are still very dominant. Many courses and guidelines are offered when it comes to writing papers and essays, and hardly any student emerges from the system without having received plenty of severe criticism and suggestions for better writing, including layout and punctuation. But, at the same time, most university students go through bachelor, master, and even Ph.D. programs without ever receiving the slightest advice about how to orally present themselves, their academic subject, or a case of public or scientific interest.

Students may have learned a lot about correct grammar and the proper use of commas, but they have never been taught or advised how to use their own voice or their own gestures, or how to stand or move in front of an audience, or where to look. In fact, many students—and quite a few of my senior university colleagues—admit that just imagining standing up alone on the floor in front of an attentive audience presents a very scary scenario. And even worse so, if they imagine having forgotten their manuscript, or being unable to read from a paper or find support in a PowerPoint screen.

In my rhetoric workshops at Roskilde University and elsewhere, students often tell me about how awkward they feel when they have to stand up and talk to an audience: they don’t know what to do with their hands, where to look, they become self-conscious in a self-destructive way, and they don’t know how to express themselves. However, if I ask the same students to interview each other in pairs for about 10 minutes, they soon engage in long and lively conversations and narratives using both gestures, mimics, dynamic voices, and they are attentive and interact with their one listener. So, to put it roughly: the problem is not that students are incapable of communicating orally, but that they are not used to and afraid of doing it in more formal and demanding situations where they have to speak to a larger audience and not just a few friends.

Reading from a manuscript might be all right in a university’s lecture hall—especially if the lecturer knows the art of staying in touch with the audience while speaking in a lively and varied manner—almost as if there were no manuscript on the lectern. But reading from a manuscript does not work well in many of the aforementioned modern rhetorical situations, like a job interview or a family gathering. Here we value something different, namely, the personal presence, the eye contact, the freshness of formulations, the intonations and responses adapted to the situation, the audience and the actual unfolding of events. We do not want to know or read the manuscript from last year, we want to experience—here and now—the visions, ideas and stories owned and presented by an actual person.

Challenging the preconceptions of writing culture

What I dare to call the preconceptions and even the heavy burdens of writing culture become evident when I ask students in a class on rhetoric to prepare a small speech on a given topic (e.g. “your favorite hobby,” or “a travel experience”) for the next day. Although I say that I do not want to see anyone read a text from a paper (or from a phone or a laptop), and that I want a genuine oral performance, most participants nevertheless want to prepare by writing a word-by-word manuscript first, and then learn it by heart. It seems natural to the students (and I have classes both with Danish students and classes with a wide range of international exchange students) that preparing a speech is best done by writing, usually alone and in silence. Perhaps it is not just students, but most people in Western societies, academic or not, who find it natural to prepare a speech by writing. But that is a preconception I want to challenge.

What often happens, when it comes to the actual delivery of such a written and seemingly well-prepared speech, is that the written manuscript appears as though still present—not in the hands of the speaker but in the back of the speaker’s head, as it were. Often enough the script becomes a disturbing rather than a supporting factor. The audience will easily detect certain modes of speaking that resemble that of reading aloud, the rhythm and breathing become different, perhaps more monotone. Listeners feel the difficulty and hesitation of the speaker trying to recall the formulations and the order of things in the manuscript, the speaker looks “inside” herself or up at the ceiling or out the window in trying to see the words as they were written on the paper or the screen.

Even though it may be difficult to gage precisely what is going on, it is nevertheless quite obvious as a phenomenological observation that a speaker who is relying heavily on a written manuscript, whether actually on the podium, left at home, or virtually present on a cell phone in their pocket, is quite likely to become a little distant, unfocused, and out of touch with the actual audience and situation. It is in the gaze, in the breathing, in the tone of voice, in the phrasing and modulation, and the speaker feels it too, perhaps, and then becomes even more awkward and nervously self-conscious. The articulation, the flow, the mimics, gestures, posture and even basic movements like walking seem to deteriorate. So strong is the dominance of the writing culture that making a “mistake” or missing something in relation to the written script seems so terrible that the speaker evidently forgets to focus here and now on actually communicating to the audience.

Of course, writing drafts, an outline, or even a fully spelled out manuscript can be a good way of preparing a speech—especially if one is constantly considering not just the topic, but also the specific audience, the specific circumstances (such as the actual place and situation), and one’s own specific appearance (including clothing and physical moves). As Cicero said, a speech must be adjusted according to such parameters in order to become fitting or apt (aptum) (Cicero, III,210). Indeed, Cicero encourages us to always look at the actual and specific circumstances. In modern terms, one might say that speaking live is always contextual, in a different and much more poignant sense than writing something that is then to be read at a different time and place.

So, Cicero’s presumably well-known dictum that “the pen is the best and most eminent author and teacher of eloquence” (Stilus optimus et praestantissimus dicendi effector ac magister, Cicero, XXXIII,150) should not be taken to rank writing over oratory, but as a way to stress the importance of gaining experience and understanding of the shifting situations: there is no one golden rule or absolute, invariable correct way of speaking, it is an art in the making. Eloquence, he writes, is not born from (following preexisting) rules, but rules are born from (having experienced) eloquence (sic esse non eloquentiam ex artificio, sed artificium ex eloquentia natum (Cicero, XXXII,146).

Preparing a speech can be done in many ways, and I want to challenge the preconceptions deeply rooted in academic culture that writing is the best way, or even the only one. Why should sitting down all alone in a small room and staring at a blank sheet of paper or a blank screen and then starting to write words be the best way to prepare a great oral performance? After all, what you are preparing for is a highly social event where you will probably be standing up or even moving about in a large room and using your voice and whole appearance to communicate with real people—and that is not just a matter of words or a writing issue.

The whole idea and common practice of preparing for live speaking by writing down words reminds me of a swimming course I had to attend when I was a very small boy. The first two hours we sat on the floor of a gym and were instructed in doing strange movements with legs and arms while the instructor was giving orders and counting. This might have worked well for some of the other kids, but I did not myself feel well prepared to go swimming in the sea the next week. It so happens that it was a very cold and windy day in spring. This was in Denmark well before any great change of climate, and due to the wind and waves rolling over my head it was quite difficult to hear the instructor counting. Swimming in the sea was rather different from doing exercises on dry land and indoors, and perhaps it would have been better to start out with some more playful exercises in shallow water on a sunny day.

And even when it comes to the didactics and process of writing, it is not necessarily the case that all the best ideas about a certain topic will pop up by themselves immediately when you sit down ready to write, and then you just have to structure them, and finally find good formulations of the various points. Sometimes it is not until we hit upon the striking formulation, and try to say out loud some brilliant words, a thick description, or a lyrical expression, that we actually realize what it is we really mean and want to say, and from there we can see how best to structure it and it becomes easier to recall. In this way actio, elocutio, and memoria direct us back and redefine inventio and dispositio—quite the opposite order of how this is traditionally taught. In academic and educational practice today, we still see a rather rigorous interpretation of these so-called five canons or five work phases of classical rhetoric (inventio, dispositio, elocutio, memoria, actio). Students are instructed to first find their ideas, theme or problem, then structure their report in main sections, then write it out in nice words, and finally print it or upload it (today’s version of memoria and actio, one might say). But perhaps it is nevertheless a common counter-experience that finding the right, striking words even late in the process of producing a report or a thesis might take us back to see what should really have been our main point and focus.

The speaking body

Overcoming awkwardness and nervousness when standing up as a speaker in front of an audience is not an easy task, and it is not just a matter of writing many good manuscripts, nor is it just a matter of reading a lot of good advice about how to think and behave and breathe and where to direct our gaze. Being nervous seems to be a very common reaction, and even though one could argue that it is not a very rational one, it is certainly no help to try to “rationalize” it away by telling yourself “don’t be stupid”, or “pull yourself together and stop being nervous”. It is in your body, and you need to work on it and work it out—or perhaps play it out, in order to become more confident, relaxed but in control at the same time. It takes a good deal of training, of direct live speaking—actio, that is—to overcome the various forms of instinctive and/or norm-based nervousness, and in my experience as rhetoric instructor the best and most direct way is to actually try out speaking with your own body and voice in a realistic but safe setting—just like learning to swim takes more than just theoretical explanations on dry land about buoyancy and propelling in liquids. One could start in the water straight away, but preferably in water that is not too cold or deep or stormy on the first day.

So, in terms of the pedagogy of teaching speech, I want to move away from the traditional focus on paper and words to a new phenomenological focus on body and voice and the experience of interaction with the audience. Being able, as a speaker, to control the performance and become confident and convincing in different challenging speaking situations is very much about a physical, corporeal experience and competence. The skills and virtues of rhetoric need to be incarnated, so to speak—they must be played or drilled into the habits, the stances, the movements, the memory and nature of your body. And the way to practice that is exactly by trying, playing, toying, experimenting: a lot of exercises involving body and voice immediately.

The crucial theoretical and methodological difference and advantage of this phenomenological approach to teaching speech is that body and voice are not seen as some secondary attributes that are to be added later after having written a manuscript. Instead, they are to be understood as the original agents that actually carry the communication. Body and voice are the conditio sine qua non of oral rhetoric, and that is where the training should start, rather than with a detour into written words.

It may seem provocative or unacademic to university students not to be allowed to write anything for a speech class. Sometimes I even boldly forbid the students to take notes in class, just to be clear about the focus I want: I urge the students to pay full attention to what is going on in the room, to how they feel themselves while speaking or listening, and to observe what they can actually see and hear when their classmates are speaking. And I urge them to focus at first on how things are being said instead of on what is being said. Focus is on the forms that deliver content. One of the first exercises, therefore, could be something like standing up one by one and saying just a few simple phrases that I have written in advance on the blackboard/screen, like “Hello everyone, my name is …, I come from …, and I am so happy to be in this class!” But this small presentation has a twist to it: it needs to be done badly, it needs to be said in a way that does not communicate well. And the students just have to find their own unsuccessful way of doing it.

This could be by speaking too fast, mumbling without articulation, grinning stupidly, fiddling distractingly with clothes or a pen, looking out the window as if bored, and so on. The more variations the better, but it has to be done using the exact same words and phrases. This goes to illustrate that important differences lie not just in the semantic or grammatical constructions, but in the actual realization that the various participants perform with their own voice and body. It can be a rather amusing exercise; we seem to get a glimpse of many a strange personality, and after that it seems like much of the nervousness disappears from the room. Students are usually afraid of not performing well enough, but this challenge of performing badly puts things into a new and much more productive perspective.

The importance of body language—or to phrase it perhaps more correctly, the importance of the integrated and communicative corporal aspects of an oral presentation—can also be illustrated by different ways of walking and standing, e.g. just getting up from a chair and walking to a podium. It does not have to be great acting; the students can quickly detect and label what sort of person or mood I seem to embody, as I get up from my chair and look at the class with an angry, a tired, a happy, a humble, or an anxious attitude. And I can give students notes in their hands with different, specific moods or personalities they have to enact without words (just getting up and walking a few feet); the other students can easily see if you are supposed to be old or young, sad or happy, etc. Again, this is not a communication by means of words, but it is an integral part of what an audience perceives every time a speaker walks to the podium.

It is quite evident from exercises of this sort how quickly we sense and recognize the sentiments and perhaps also the personality of a speaker even before a single word has been said. This is a basic human capacity and does not happen through any use of verbal language or through an analysis of signs or signals, it is not through an act of calculation or translation, nor is it through any kind of reading or decoding or help from a popular or scientific book about “body language”. It is due to our fundamental body-phenomenological understanding of others and our surroundings. This capacity for seeing and understanding other persons is a basic human condition, according to Martin Heidegger in Sein und Zeit (first published 1927). We exist in this world as in a with-being with others, or as he puts it: “Das In-Sein ist Mitsein mit Anderen” (Heidegger, 1927:118). The others are phenomenologically speaking given for us, this is evident (from the outset, Heidegger transcends the problem of whether there are other minds or subjects in the world, a problem that seems to have traumatized western philosophy since Descartes established his abstract “I” through an empty cogito).

In traditional academic contexts it might be rather unusual to include observations and thoughts about your own individual body, movements, and appearance, but for many students today it connects well with a more popular and even trendy preoccupation with body-culture, sports, fitness, performance, yoga, singing—even breathing exercises might not seem too silly to them, and this can be very useful as a way into practicing speech. Participants in a speech class often have various resources stemming from non-academic areas that can prove to be of use, and they can inspire each other to think more positively about working and communicating with their bodies. The initial exercises should point to the importance of being in every sense present and aware of the kairos, the here and now of oral communication.

The voice and the mood

A poem can be understood as a condensed expression. In German the etymological relationship between dicten, to make a poem, and the verb for condensing or making tight, is easily seen. The English words poem and poetic stem from the ancient Greek word poesis which has to do with being crafted, created or manufactured. So, I tell my class of students that a good poem deserves to be recited in a slow and well-articulated fashion, so that we, the listeners, can better appreciate and enjoy how well it has been crafted in every sense and detail. It is often one of the first days in a workshop that I ask the students to memorize a short poem of their own choosing and prepare to recite it in class, loud and clear. It soon becomes obvious that a monotone reading-like performance does not do justice to the poems, but that a well-performed recitation of just a few carefully crafted expressions can have a powerful impact on an audience—even though that particular audience might not normally be the greatest fans of poems or lyrical performances.

One practical trick to heighten the understanding of what the right voice and words can do is to ask the performing student to speak behind a screen or even behind a half-closed door—and perhaps even with their back towards the listeners. Then, of course, one has to speak in a loud and well-articulated manner in order to be heard and understood, but the mere awkwardness or silliness of this set-up may also serve to free some students of habitual restraints and allow them to experiment more freely with their voices. After some trials of this, the speaker takes up a more normal position and recites the poem standing in front of the rest of the class. It is not at all easy for everyone; many become too self-conscious of the way they appear or talk, and now sometimes the otherwise well-memorized poem seems to disappear from memory or lose any magic it might have had.

One way, then, of shifting the focus back to where it should be—namely, to experiencing the content of the poem—is to ask the student to teach the poem to the rest of us in the class, i.e. to say it nice and clear one line at a time, and wait for us to repeat each line in chorus. If the audience cannot repeat the line, then clearly it was not well communicated. Most often the reciting student becomes so eager to have the lines correctly repeated by the class that it immediately improves not only volume and pronunciation, but also eye contact and accompanying gestures (that were perhaps absent before or rather rudimentary or distracting). It is a simple point, but worth pointing out in class in connection with these poem exercises, that we really should be speaking in order to communicate some content to our audience, and that we therefore really should be paying attention to whether the audience can actually hear and understand us—and that is every time we speak.

Often the participants in the middle of such an exercise involving reciting a poem have trouble remembering the text; all of a sudden, they forget the next line or mix it up, even though they have practiced well at home and selected a fairly short text. This is where they would like to take a look at their notes, their phone or laptop, and read the text once again or several times quickly before continuing. This is where I show them an alternative way of remembering the text, namely, by looking for the elements in the poem that can be illustrated by means of gestures, changes in posture, direction of their gaze, and by different intonations, volumes, pitch, etc. And even if there is little to find in the poem that can be easily illustrated or supported in this physical way, there is still another way to support the memory: namely, by rehearsing on the floor and, so to speak, “lay out the flow of the poem on the floor”. One says the first and perhaps second line standing in the middle (normal speaking position), then moves a few steps to the left to say the next lines, then a few steps to the right to continue, and then back to the middle where the last lines are said. This very simple choreography does not make it harder to remember the text, though it seems like an additional element; it actually makes it easier. The floor becomes a helper—and this goes for long and more freely formulated speeches too—and the floor of the room is not a dangerous open and empty space, but a guide to structure and to obtaining a calm pace and flow, avoiding all sorts of ideas and words becoming mixed up in a bundle.

To further encourage experiments with their individual vocal capacities, I might ask students to imagine they are speaking to children, to a very noisy crowd, to an audience of old people with hearing problems, or a group of tourists with a limited understanding of English, or maybe to whisper the poem as if it were a secret. The different versions of the same poem may seem silly, awkward and far from any serious public speaking, but all too often the students need to become aware of the immense potential of their own individual voices and the many rhetorical tools they actually have to hand but rarely have considered implementing in a skilled or strategic way: volume, pitch, phrasing, tempo, pauses, and even breathing.

Although some of the exercises and different versions of a poem may seem silly, it also happens quite often that a student performance makes a poem come across in a strong, deep, and moving way. I encourage the students to enjoy that, of course, but also to reflect on and try to put into words what it was in that individual performance that had this effect. Something about the voice, or was it the words, or something unique and personal in that moment, in that situation? It can be hard to describe these qualities or phenomena of a successful recitation, but it is quite clearly felt by everyone who is paying attention when it all “comes together” and “rings true”.

It is also a curious fact, and easily recognized by the students, that the sound of a familiar voice immediately activates a stock of sentiments and expectations. And even a complete stranger on the phone does not have to express many syllables before the specific qualities of that voice affect us and put us in a particular mood. We receive an impression of much more than just the age or gender of the other person. Most often it is hard to specify the experience of the quality or “tone” of the voice as anything measurable or easily categorized, but nevertheless it is clearly felt. In phenomenological terms, it is evident that the sound qualities of a voice can put us in a certain mood, or affect the mood we are in. And according to Heidegger we are always in the midst of some sort of “mood” or “attunement”. The German words (“Befindlichkeit”, “Stimmung”) that Heidegger introduced in Sein und Zeit (Heidegger, 1927) in order to describe how humans fundamentally find themselves in the world, or how they “exist”, are notoriously difficult to translate into English (in Danish it is a lot easier: “Befindtlighed”, “Stemning”).Terms like “mood” and “attunement” may seem fairly close, but lack the clear etymological connection to “voice”, so easily recognizable in the German “Stimmung”, as the German word for a voice is “Stimme”.

Heidegger is trying to overcome the long-standing problem in Western philosophy since Descartes of a subject-object dichotomy, and he does not accept the point of view common in the widespread variations of positivist theory of knowledge that we first and foremost are (or should be) “neutral” or “objective” minds registering impressions from things around us. We are always in a certain mood or attunement, this is a fundamental condition of our awareness, of our “being-in-the-world”, and therefore it makes good sense in terms of teaching speech to focus on what the qualities of a voice can make an audience sense and experience, and in a wider sense to focus on how the overall performance and presence of a speaker in oral communication can appeal to, change, and create the mood and attunement of the listeners. This “mood aspect” of communication is not to be understood as something that is just added later as a sort of adornment to the “original” or “denotative” written content. The Danish rhetoric professor Jørgen Fafner in his book Retoric (Faffner, 2005:140) argues strongly against any such simplistic ornatus theory that assumes that qualities and style are just a sort of “dressing up” of the original point or argument. That would be to misunderstand the intricate relation of content and form.

The phenomenology of taking the floor

Many of the initial exercises in my speech workshops are thus oriented towards the phenomenon of taking the floor; I want the participants to practice, experience, and reflect on what it is that typically happens with our attention (both speaker and listeners) when someone starts speaking. I want everyone to focus on what is happening, rather than on what words are actually being said. Everybody knows that the introduction of a speech (exordium) is important, but what is rarely in the speaker’s notes is that the communication between the speaker and the listeners begins before the first word is uttered. And when the words begin to be uttered, it is typically something specifically oral that counts at first, such as voice quality, gaze, and mimics—and not something that belongs to writing or a dictionary. Here it is all about understanding what it is that is going on in the room and in the situation, in the exchange between orator and audience.

In the following, with my own short description of the phenomenology of taking the floor, I want to point out three phases of attention in the first part of a typical instance of oral communication. It must be underlined that these proposed three phases are not sharply distinct but usually blend and replace each other unnoticeably. But for a trained speaker this also comes naturally, just like the classical division of a standard speech (dispositio) might be well drilled in, and likewise it is possible to allow for variations and even to radically shift the order of things and still succeed.

1) At first the attention is naturally on the speaker as a person. The speaker is getting up and walks onto the floor or up to the podium and looks out over the audience without yet having said anything. At least, this is the recommended way to start; nervous speakers are usually eager to commence speaking and tend to start talking too early, and this is not good, neither for their ethos, nor for the reception of their first words. I advise starting generally with a fairly long silent moment after having taken the floor and put oneself into a strong and grounded position. The speaker should breathe well and deep, look confident and friendly (as a general rule, not without situational exceptions) and wait for the gaze and attention of the majority of the audience to focus on the speaker. This is advisable because at the beginning of a new performance the audience’s attention is quite naturally directed towards sensing, estimating, and perhaps re-evaluating what sort of person and personality is going to speak to them. In this phase, the audience is trying to fine-tune what has been called the initial ethos (McCroskey, 1978:71) of the speaker, and they do so by considering the way the person looks, dresses, walks and moves, takes a position, displays gestures, facial expressions, and so on. All of this is non-verbal communication, and even if a speaker on the way to the podium utters a few words like “OK” or “Thank you”, this is received not so much as meaningful words, but more as signs of a certain mood and personality. They belong, in a way, in the same category as other non-verbal sounds, e.g. the footsteps or noise from clothes and jewelry.

As the speaker, one has to endure (or even better, to enjoy) that right now, everybody is looking at me and more or less trying to figure out what sort of person I am, how my speech will be, how trustworthy I am, etc. I am being evaluated right from the (non-verbal) start, and lots of different categorizations might be at play, even bias and prejudice, cultural norms and individual preferences. It is not necessarily problematic, but usually we are (mostly without any deliberate conscious reflection) categorizing as male/female, young/old, fat/skinny, but perhaps also in more situational categories like entertaining/boring, positive/negative (to the listener’s own view of the issue debated), modest/bragging, nervous/self-confident. The speaker is well advised to be informed about the audience’s attitudes and preferences (and possible prejudices), and to try to accommodate and control the impressions given in those first moments. This includes choice of clothes, the nature of a smile or a nod, and the waving of a hand. Today, in video clips of American politicians entering the stage to give a speech, or an actor coming on stage for a talk show, it is quite common to see the entering character point to someone in the back of the room and wave eagerly. One might suspect that there is not always someone they recognize as a favorable supporter back there—but it seems to be part of a timely visual rhetoric.

Through the attitude and very first non-verbal communication of the speaker, it is also shown in what way the speaker recognizes the presence of an audience and wishes to relate and share. What Aristotle calls eunoia—the display of good will towards the audience—is at work before the first word is uttered. In Roman Jakobson’s terms, one could say that, in this first phase of taking the floor, it is both the emotive and the phatic functions that are predominant at the same time (Juel, 2013).

2) In the second phase of opening a speech, the attention is on the common presence in time and space. As the first words are being uttered, the main attention is probably still on the speaker’s voice, person and ethos, but soon the clever speaker will typically try to move the attention away from just “me”, and on to an “us”: “We are here together today”, “So happy to see you all”, “Glad you made it this early despite the bad weather”, “Such a nice room we are in, I hope you are all comfortably seated”. One way of trying to establish a “we” and a favorable common ground is to start with flattering the audience, in classical rhetorical terms with a captatio benevolentiae: “How nice to see so many bright and intelligent students this morning!” In all of this it is the phatic function or the social aspect of the communication that is now predominant. The speaker strives to establish common ground and presence with the audience.

There is much good advice to be found in classical texts as well as in modern handbooks about how best to begin a speech. Some suggest starting with a quotation, a joke, or an anecdote (Gabrielsen & Christiansen, 2010). Cicero would advise the speaker to adapt to the audience, the situation, the topic, and find what would be becoming, also to yourself as the specific person you are. What is interesting in all of this, however, from a phenomenological point of view, is what happens with the attention (of both audience and speaker) during these initial remarks: it shifts away from being focused on the “I” of the speaker to now being focused more on the social aspect or the “we” in the room, here and now.

3) In the third phase of the opening of the speech event, the attention is directed towards the topic, the case, or question that is to be dealt with. In classical terms this could be achieved by an overview of what is to come in the speech (partitio) or by an account or narrative (narratio) concerning the situation and topic. It is of course also possible to start a speech by stating the issue straight away (in media res), but even so a good deal of the attention will usually and nevertheless be on the speaker at first, and only gradually shift to a focus on the subject, the arguments, the consequences and perhaps decisions to be made. As a speaker you run the risk that no one listens to what you actually want to say if you do not at first spend some time and energy on showing who you are and on establishing a presence and contact as the basis for subject-specific and persuasive communication. In this, the third phase, it is, to use Roman Jakobson’s terms, the referential and conative functions that begin to prevail.

To sum up, one can say that this phenomenological observation of a common shift of attention at the beginning of a speech identifies a move from “me” (or “him/her”) to “us”, and then to “that”. First, we see the speaker, then we see we are together in this room and situation, and then we can start looking at the issue and maybe see what the speaker is really trying to show to us, that is, the pistis or point of the speech. Indeed, to explain this phenomenon I sometimes refer to an analogy of film-making: first the camera is focused on the speaker walking up to the podium and taking a stand, then it is on the speaker and audience together in the same room, and after that the film editor (the competent speaker) shifts the scene and starts showing the issue or problem or story that usually takes place somewhere else. The speaker directs the attention of the audience, but initially a lot of attention is usually on the speaker and on the social event of being together as speaker and audience.

Individual and yet social skills and competences

Understanding the basic phenomenology of “taking the floor” is one of the key reflections developed during the intensive rhetoric workshops I have practiced over a number of years (Juel, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2016). Participants have been university students at all levels, Danish and international, as well as academic colleagues and other citizens. The workshops are based on practical and collaborative on-the-floor exercises, followed by discussions and reflections, and also supported by theory, concepts and principles from modern and classical rhetoric. Aristotle, Cicero and others still have a lot to say, but in my experience, it is hard for students today to read and “listen” to the old masters, unless linked to their own personal and sometimes very new experience and feelings connected to various challenges of oral communication. Reading textbooks and writing manuscripts cannot stand alone, and it is hardly ever the best road towards personally achieving fundamental skills and competences, and it is not even the best way for an individual to develop a specific speech for a specific occasion.

It should be evident that speaking and communicating well is highly dependent on the personal use of voice and body, or perhaps it would be better to say that communicating by speech is highly dependent on an individual vocal and physical activity. It is also fair to say that we have different voices and bodies, a lot of individualization and identity is connected to how we sound and appear, and we have different talents, skills, inhibitions, experiences, competences, possibilities. But at the same time, speaking in order to communicate is also in essence a very social activity; there can be many different types of situations, audiences, contexts, constraints, supports, and interactions as well as socially generated norms, standards, and expectations. In terms of the pedagogy or didactics of rhetoric, the beautiful paradox is that speaking is a very individual skill, but it is at the same time best learned when tried and developed in a collaborative and socially safe zone. Testing and developing speech elements directly by live interaction with an audience consisting of friendly fellow students is, in my experience—and perhaps not surprisingly—a lot more productive than sitting down writing and reflecting in isolation.

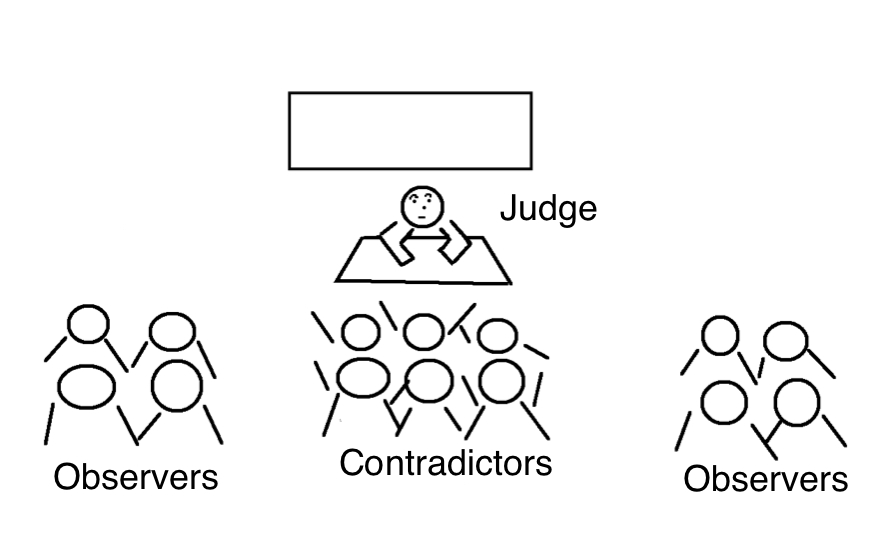

Speech-line – collaboration on actio

One way of teaching the highly individual skills and competences of speaking well to a large group of participants in a short time in an effective—and usually very entertaining—manner is to practice the speech-line method (Juel, 2015). This can be done booth indoors and outdoors. All you need is some free space, like an open floor, or even a corridor. The participants form two rows, facing each other, two or three meters apart. Each one in row A then has a temporary partner in row B, and vice versa, and the two have to be very focused on communicating together, taking turns as speakers and listeners, and giving feedback, following some simple instructions given to all. Then, after one round of speeches and feedback, row B or A moves along one position, so that everybody gets a new partner.

Everybody in row A will start talking at the same time for around a minute or so about their individual subject—an early draft version, perhaps just sketching the idea for a speech in a straightforward manner. Because of the noise from all of the other people talking, it will automatically become necessary to articulate really well, to support with gestures, to maintain eye contact, and so on. If the listener in row B cannot hear or follow what is being said by their partner in the opposite row, the listener must ask the speaker to speak up, repeat, or clarify the points made. But otherwise the listener should be very supportive and affirmative, nod and smile and follow closely what is being said. In earlier exercises we have already established that being a positive and supportive audience quite clearly helps the speaker to find the words, the energy, a likeable ethos and to generally perform better.

In the first round, the speaker from row A does not receive any feedback until the partner in row B has spoken. Then, usually to the surprise of the participants, I ask row B to re-tell to their partner in row A what they have heard, what they recall from that first presentation. And they can also add whether there is something they would like to have better explained or to hear more about. This is quite an effective way to show the speakers what they essentially communicated—and what was more or less lost, perhaps because it was unclear, redundant, meta-communicative or otherwise off the point. I stress that this is not so much about testing how well the listeners remember, as it is about how much the speakers succeeded in relating to their partner.

If the instruction for the first round was to speak for about a minute about, for example, a favorite hobby, then the instruction for the next round (after having switched partner) could be to talk again for a minute or a little longer about that hobby, but this time to include a very specific example, some detail that the listener can easily visualize or even smell or taste what you are doing or enjoying when engaged in your hobby. This time the speaker in row A receives feedback straight away about what was good, vivid, interesting, and questions and suggestions for further elaboration of the short speech about the hobby. Then row B speaks and receives feedback.

Having moved again to a new partner, the instruction could be to keep the example/detailed description, but this time also to stress why this hobby or activity is something good, or how it is joyful to the speaker. And this could also be where a second point or value is introduced, like why this hobby would be good for everyone, not just for the body but also for the soul and spirit, or something like that. So, the little speech, now around one and a half minutes long, should explain what the hobby is about, why it is a good hobby in at least two ways (e.g. for the speaker and for everyone, or for the body and for the soul). The order of the different parts is up to the speaker, but during feedback the listener can advise them to change it or to develop the speech in different directions.

Once more, partners are switched and speaking time raised to around two minutes. When the two minutes are about to be up, I usually clap my hands or ring a small bell to indicate that now it is time not to stop, but to elegantly round up the speech. In this version the speakers need to include a “rebuttal”, the refutatio in classical terms, which means to account for some sort of objection to the hobby, e.g. that some might say it is too expensive, or time consuming, or bad for the climate, and then counter this imagined objection with a positive point or argument. And also include, perhaps, other persuasive rhetorical features like a “rhetorical question” (“Have you ever tried riding a horse at night on a beach in moonlight?”) or a direct, flattering appeal (“You should try mountain-biking too, you are so young and sporty with a great body for that”), or perhaps a three step alliteration (“It is fun, it is free, you can do it with your friends”).

One very effective rhetorical feature is a sound-bite, i.e. a short, catchy phrase indicating the essential point of the speech. It can also be described as a sort of slogan or motto, something that is easy to say and easy to remember, perhaps because it has lyrical or acoustic qualities like alliteration. In order to develop/choose a good sound-bite, the speaker usually has to ask the listener for ideas and advice, and also to practice repeating it a couple of times in various ways. A sound-bite needs to be “drilled in”, it must be repeated many times with variations in order to be properly “owned” by the speaker: only then can the speaker say it with sufficient conviction and emphasis during a speech, e.g. at the beginning, middle and end. A good sound-bite may often look strange and redundant if written out in a manuscript, but well-crafted and rehearsed it can significantly enhance a speech. A sound-bite is a truly oral attribute and it needs to be incorporated not just in the text but literally in the speaker’s mouth and performance.

With speech-line exercises like these it is possible to develop all participants’ individual speeches and have the various ideas and versions tested immediately. This includes receiving feedback on the use of the voice, gestures, posture, the level of energy and enthusiasm too. The speaker can freely decide what good advice to follow and can try different versions, thus it is still a very personally owned and generated performance, despite the different contributions from the trial listeners and the general advice from the instructor. Within just one hour, a class of students can—without preparations or writing anything—develop fairly good speeches using this direct actio speech-line method. It can be done with more than 100 students at the same time out on the campus grass, it just takes a bit of discipline (at least at my university), and it can be done in different languages and even with professors in rhetoric—you just have to get the participants to play along and enjoy it.

The speech-line method can be used not only for building up a speech by gradually adding elements and testing the formulations and the body-voice performance, but also for reducing the length and complexity of an issue and clarifying the essence or point that the speaker wants to make. In workshops with Ph.D. students or other advanced academics and professionals the problem is often not to find material or points to present, but to boil it down to something essential that is easily communicated but still leaves the audience with a vivid and fair insight into the perhaps very specialized and complex subject matter. In this variation of the speech-line method one might begin by asking participants to speak freely and for fairly long about the subject matter (e.g. their own Ph.D. project) to their listener, who then in the feedback gives a short version of what was heard and understood, and then asks for more explanations, examples, etc.

The informal speech-line way of talking at greater length to one attentive listener while standing up resembles the walk-and-talk exercises often used in other workshops and at meetings, where the object is to become clear about something by interviewing each other in pairs (or greater numbers) while walking along. It is generally well known and accepted that physical movement—taking a walk and talking to a colleague—can help clear the mind and/or bring about new ideas and formulations. A speech-line can be used to assemble or build up a speech from scratch, and it can be used to condense or boil down a lengthy and complex matter. The physical or bodily involvement as well as the collaborative interaction play an important part in both of these rhetorical work processes, and it would not be fruitful to regard it as design decisions created by isolated individual brains.

Collaborative work on developing a particular speech can be done in many other ways than with a speech-line or walk-and-talk exercise. A generation of ideas can be done by means of a common brainstorm where a group contributes with whatever ideas pop up—but this may of course be more structured and organized around different questions or templates. One variation could be creating a mind-map (which is also a well-known tool) without writing words but using different drawings and symbols instead.

As mentioned in connection with the exercise involving reciting a poem, various forms of visualizing and making drawings are powerful tools for memorizing (Fernandes & Wammes & Meade, 2018). Curiously, perhaps, it seems easier to recall an image and a phrase together than just a phrase on its own. But it is not only the memoria part of the process that can benefit from visual input; the inventio part, the generation and clarification of ideas, can also be helped along by drawing, alone or together in a group. Drawing is essentially something you do in order to present something, and it can be a way to see things in a new light. Most adults, however, are rather reluctant to go back to this form of expression that they last used when they were children, and to share it with others today, but once the awkwardness has been overcome it can become a very productive, amusing, and inspiring tool in a speech workshop.

Speech, thought, writing – phenomenology and hermeneutics

Mastering a speech situation demands paying attention to the actual audience, and similarly to write in a catchy and relevant way demands also a certain degree of attention being paid to the readers one wishes to reach, perhaps even a visualization of the readers’ reactions, objections and comments. But in the oral situation this respect for the audience, the entire feedback aspect, is much more vivid and direct. Indeed, writing well for a specific audience—and this includes writing a speech manuscript, if one wishes to do so—demands some experience and knowledge of the oral interaction with an audience: writing skills presuppose speaking skills, not (just) vice versa, one could say.

Walter J. Ong is quick to point out the principal aspect of the common, everyday experience that we often try to say the words tacitly, inside ourselves when trying to write: “To formulate anything I must have another person or other persons already ‘in mind’. This is the paradox of human communication. Communication is intersubjective” (Ong, 2002:172). J. Faffner even goes as far as saying in his Rhetoric: “…writing is only a copy of speech—and an incomplete one, at that. The speech has priority in regard to the writing” (Faffner, 2005:67, translation: HJ).

Hans-Georg Gadamer, too, highlights orality in his Wahrheit und Methode. His hermeneutical approach can be seen as a frame for interpreting all kinds of texts, but also as a general theory for the humanities and for humanity, in which the principle of seeking mutual understanding and insight through a conversation (as opposed to an instrumental power and control relation) becomes the guide for all sorts of understanding and communication, including written communication. It is thus not just an accidental metaphorical remark when Gadamer summarizes the ideal of sharing “horizons” as that of making a text speak: “Through the interpretation the text must come to speak […] There is no speaking that does not unite the speaker with the one spoken to” (Gadamer, 1975:375, translation: HJ).

One of Walter J. Ong’s rather polemical formulations reads: “By contrast with natural, oral speech, writing is completely artificial. There is no way to write ‘naturally’” (Ong, 2002:81). In his view, writing is a derived but also very useful technologizing of the word, as also indicated by the subtitle of his book Orality and Literacy – The Technologizing of the Word (1982). Naturally, writing should be appreciated as a culturally developed and smart technique to store and to broaden in time and space the reach of the spoken word. But then again, spoken words can be seen already in themselves as a technical refinement, an articulation of the otherwise rather hidden things you have in your heart. Even gestures, signaling and visualizing, can be considered, I would suggest, as an evolved capacity for expressing at a larger distance an even more basic close-up corporeal form of communication (caressing, slapping, carrying).

However, my point is not to try to search for some basic “original” or authentic communication (a notion sharply criticized by Adorno in his Jargon der Eigentlichkeit – Zur deutschen Ideologie (Adorno 1964)) before literacy or even before digital media, but to question philosophically the rather common assumption made in many a handbook about rhetoric and speech that first we have to think about what to say, then we have to write down these thoughts, and then we can go and deliver our thoughts by means of the words we say to the audience. This seems so natural and basic, but it is worth considering whether this is not essentially a misleading heritage from the era of writing and literacy, an era of writing being in higher esteem (especially academically) than speech—a preconception that is now challenged by the development of digital and audiovisual media. What becomes questionable, or at least somewhat blurred now, is whether we actually need this “detour of writing” in order to get from thought to speech. And is it not questionable that we should actually be “thinking” in such a way to begin with, juggling with something like “thought” elements before they are turned into words? Would such “thoughts” be part of a sign “system” to which one can find a “translation key” turning them into verbal language that can be pronounced and be heard by the listener, who then in turn “translates” the words back into “thoughts” (being now in the listener’s mind)?

This is where Martin Heidegger suggests another perspective in Sein und Zeit, as he sees a close connection between our always already-attuned and interpretative understanding of the world, the articulation in language, and our immediate communicative “being-together” (Mit-Sein) with other humans. We are always, by means of our corporeal, attuned and “moody” being, already “there” and “present”; and we are projecting actions in a participatory and interpretative way, ready to articulate and share with others in and through language. Language, understanding, and experience of the world are closely connected, but the mood or attunement is already an opening onto the world and onto ourselves.

Heidegger is not to be understood from a standpoint of dualism between subject and object, or between soul and body, or on the basis of a truth concept based on a correspondence between a proposition and reality. On the contrary, that is the metaphysics he is trying to deconstruct. And it is remarkable how he foreshadows the grandiose existential-ontology of his Sein und Zeit in 1927 through a close and peculiar reading of Aristotle’s Rhetoric in the 1924 lectures at Marburg (first published 2002). Heidegger is not trying to read Aristotle’s Rhetoric as a handbook in strategic communication, but as a philosophical definition of the human as a speaking and listening being, and not least, as a pathos-being. The interpretation of pathos is a controversial subject (e.g. Oele, 2012), but Heidegger underlines pathos as that phenomenon of being moved or transported (Mitgenommenwerden) as a human. And it is not just “the soul” that is being moved; Heidegger explicitly talks about the corporeal (leiblichen) aspect, even in a section heading: “Das pathos als Mitgenommensein des Menschlichen Daseins in seinem vollen leiblichen In-der-Welt-sein” (Heidegger, 2002:117). This heading is difficult to express in English but one attempt could be: “Pathos as human awareness being moved in its entire corporeal being-in-the-world” (translation: HJ).

It is true that Heidegger, in his Sein und Zeit, seems to avoid using a word equivalent to “body” (das Leib is after all mentioned, e.g.:117). However, the suggestion of a phenomenology of the body, or a corporeal phenomenology, later to be explicitly developed by Maurice Merleau-Ponty, can be seen throughout Sein und Zeit in the unfolding of human existence or way of being-in-the-world as being attuned, being in a mood, being “thrown” into the world, and in many references to crafts and farming as well as the major division of Zuhandenheit/Vorhandenheit, which is Heidegger’s attempt to avoid or dig beneath the traditional metaphysics and theory of knowledge of “things”. We are not blank, immaterial subjects neutrally observing objects around us, some of which are giving off sounds that can be processed and translated into words, but we are typically attuned and engaged in projects involving immediate use of tools and materials, and immediate recognition and understanding of other beings present in a similar way.

Merleau-Ponty is perhaps more direct in linking thinking and verbalizing and body into one and the same process: “To the one who is speaking, the words are not a translation of a thought already made, but the accomplishment of the thought” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945:217). This could be seen, I hope, as contributing to a philosophical and didactic justification of the impromptu actio exercises that I advocate as part of a fair road towards rhetorical competences, a road that often proves more direct than the detour of writing manuscripts. Merleau-Ponty states: “The orator does not think before speaking, nor while he is speaking; what he is saying is his thoughts” (Merleau-Ponty, 1945:219). Consequently Merleau-Ponty also talks about how gestures and actually the whole body become the very thought or intention, that it is showing us—it is the body that is showing, the body that speaks (Merleau-Ponty, 1945:239).

Gestures and mimics, as well as tropes and voice qualities, should therefore not be considered as something extra added to the speech at the end of a development process, nor are they merely ornamentation of an argument (though the classical Roman concept of ornatus seem to suggest that). The good speaker is not one who is also speaking with the body, but one who is the speaking body. Once again: it is a matter of really being there, not hiding behind a manuscript paper, but daring to be present as a speaker, and to reach out to the audience in order to move them, and make them see what you present to them and want them to see—and “from your point of view”.

It is worth remembering that even Plato, who was rather skeptical of the professional sophists and rhetoricians of his time, nevertheless saw some dangers involved in the media of writing; namely, that the lively presence of the speaker could be somewhat lost, the message could be fixed and distanced from its personal creator (in Phaedrus, Plato, 1961). Paul Ricœur also points to this difference between speech and writing in his Interpretation Theory:

“But in spoken discourse this ability of discourse to refer back to the speaking subject presents a character of immediacy because the speaker belongs to the situation of interlocution. He is there, in the genuine sense of being-there, of Da-sein […] With written discourse, however, the author’s intention and the meaning of the text cease to coincide.” (Ricœur, 1976)

Rhetoric, philosophy and the need for oratory skills today

When I am teaching skills in oratory to today’s students, the many actio exercises go hand in hand with also reviving the classical teachings of how to structure a speech, how to make it appealing (using logos, ethos, and pathos), how to distinguish the main genres and styles, and how to employ tropes and figures of speech. But the classical concepts are not taught as theoretical instructions on dry land before swimming, that is, not as paper wisdom before going on the floor. Workshop participants try out for themselves in small, safe live situations, they experiment and play, receive feedback from their peers on what works and what does not, and they soon develop a sense of their own special skills and competences as well as a sense for general rhetorical tools and insights. Rhetorical performance is, to a large extent, an art and a craftsmanship that needs to be guided, developed, and rehearsed, adapting to the individual’s different potentials and in cooperation with peers. This is the didactic opening, which at the same time opens up an understanding and revitalization of classical concepts.

At first some are not aware of the long tradition of rhetoric (after a speech-line exercise one student once told me that he found it a great idea to include a “rebuttal” in his speech, and he congratulated me for coming up with this new and fresh idea!). But having been on the floor and having discovered the almost unlimited toolbox at their disposal, the students usually find classical rhetoric much more interesting. And as I encourage them to also observe and describe what they experience and feel both when speaking and when listening, and to note how different postures and styles of gestures and movements can help them to achieve, they also begin to appreciate the phenomenological and philosophical apparatus I sometimes dare to sketch—and to develop further collaboratively in the classroom.

My own professional ambition is not only to prepare the students and workshop participants for future exams, job interviews, ceremonial speeches, NGO rallies, or political talk shows, but also to understand better, through all of the actio experiments and reflections in class, how oral communication really works. And it is very rewarding to experience what happens when people actually succeed in saying what they mean, and mean what they are saying. It has a remarkable effect on both the speaker and the audience: we see the issue discussed in clearer light, and perhaps that may still contribute positively to an active, democratic citizenship. Rhetoric is about live interaction, resolving an issue and moving and improving, not just the audience, but also yourself—and perhaps the planet.

References

Adorno, Theodor W. (1964). Jargon der Eigentlichkeit – Zur deutschen Ideologie, edition suhrkamp.

Carlsen, Sine & Juel, Henrik (2007): Speaking at Speaker’s Corner – the rhetorical challenge and didactic considerations, http://www.henrikjuel.dk/Essays/SpeakingSpeaker’sCorner.pdf

Carlsen, Sine & Juel, Henrik (2009). Mundtlighedens Magi – retorikkens didaktik, filosofi og læringskultur. Handelshøjskolens Forlag.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1967). De Oratore, The Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press. http://www.thelatinlibrary.com/cicero/oratore3.shtml#1

Fafner, Jørgen (2005). Retorik. Klassisk og moderne, Akademisk Forlag.

Fernandes, Myra A. & Wammes, Jeffrey D. & Meade, Melissa E. (2018). The Surprisingly Powerful Influence of Drawing on Memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2018, Vol. 27(5) 302–308.

Gabrielsen, Jonas & Christiansen, Tanja Juul (2010). The Power of Speech, Hans Reitzels Forlag.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1975). Wahrheit und Methode [1960], 4te Auflage. Tübingen.

Heidegger, Martin (1927). Sein und Zeit. Max Niemeyer Verlag, 1967.

Heidegger, Martin (1924). Grundbegriffe der Aristotelischen Philosophie, Gesamtaus- gabe, Band 18. Vittorio Klostermann, 2002.

Juel, Henrik (2005): Communication at Speaker’s Corner (Movie,10:36), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qhXyT9VPLlE

Juel, Henrik (2010). ”The Individual Art of Speaking Well – teaching it by means of group and project work” Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift, nr. 8. http://www.henrikjuel.dk/Essays/TheIndividualArtofSpeakingWell.pdf

Juel, Henrik (2013). Communicative Functions. Essay, pdf, www.henrikjuel.dk/Essays/CommunicativeFunctions.pdf

Juel, Henrik (2014). ”The persuasive powers of text, voice, and film – a lecture hall experi- ment with a famous speech”, Conference Proceedings, Amsterdam, 2014, ISSA – Inter- national Society for the Study of Argumentation.

Juel, Henrik (2015): “Speech-line – a method for teaching oral presentation”

http://www.henrikjuel.dk/Essays/Speechline.pdf

Juel, Henrik (2016): Please don’t write your Speech! (Movie, 1:07) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9PWZ-sy7sF8

McCroskey, James C. (1978). An Introduction to Rhetorical Communication. Englewood Cliffs.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice (1945). Phénoménologie de la Perception, Gallimard.

Oele, Marjolein (2012). Heidegger ’s Reading of Aristotle’s Concept of Pathos, University of San Francisco Scholarship Repository: http://repository.usfca.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=phil

Ong, Walter J. (2002). Orality and Literacy – The Technologizing of the Word (1982), Routledge.

Plato (1961). The Collected Dialogues, Princeton University Press.

Ricœur, Paul (1976). Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Texas Christian University Press (full text available in Danish, translated by Henrik Juel: Fortolkningsteori. Vinten, 1979).