Mainstream economists claim that economics is an objective and empirically tested science – contrary to the humanities and soft social sciences. According to this view, economics is beyond the influence of ideology. It represents the rational way of analysing economic welfare – not influenced by political consideration. Therefore, it is explicitly stated within the Treaty of Lisbon that the board of directors of the European Central Bank must not take any direct instructions from the European Council to secure objectivity in the European monetary policy. Unfortunately, economic theory is not neutral. It cannot be separated from the vision and the fundamental assumptions which lay behind the economic model employed when policies are decided upon. The so-called general equilibrium model is firmly relying on market theory and ordo-/neoliberal ideology.

Introduction[1]

Accordingly, this paper is about the economic misfortune of Europe dominated by ordo-liberalism and neoclassically trained economists: how bad or misunderstood macroeconomic theory has contributed significantly to the economic and social tragedy, which is unfolding in Europe; mainly in the so-called periphery of the euro-zone, but with repercussions for all the EU countries – perhaps with the exception of Germany, although there are today more poor people in Germany than 10 years ago.

My focus point will be on the role of the mainstream macroeconomists, who represent a clear majority among the EU advisors and the teaching staff at the faculty of economics all over European universities. How can they go on being so wrong in their analyses of the economic consequences of the European Monetary Union and of austerity policies in general within EUrope?

There is a certain irony related to this development within the European Union (for short the EU). Originally, it was set up back in 1957 to prevent future belligerencies between the major European nations. But, one consequence of the negative consequences of the economic crises and the dictates from Berlin/Bruxelles is that member-countries are becoming more antagonistic, there is an increasing risk of a renewed warfare, fortunately not fought with weapons; but instead with money, debt and severe creditor conditionalities, which can have nearly as devastating consequences as warfare for ordinary people. The present days’ generals – in Europe at least – are the bankers, the multinational firms, the economists and the Bruxelles-based bureaucrats, whom the elected representatives for the European peoples seemingly have difficulties to resist, domestically as well as at the European level. So, my paper will be more on economic ideas, rather than on numbers. Although it is difficult to be believed for ordinary people(please, do not be too surprised), when you read on, and realize how mainstream textbooks pretend to make a proper analysis of the current economic disaster.

In some way Europe has been sleepwalking into this nightmare, because no one intended it to happen and only a few saw it coming, because misleading general equilibrium models were setting the analytical frame and the discourse. But even worse it is that these models are still in use, so no one can know when the nightmare is going to be over. If national governments and the European Council go on taking advises from the present days’ generals, there is a looming risk that the under-performing of the European economy will drag on into an uncertain future – the similarities with the depression of the 1930s are striking. Do not forget: unemployment in Europe as a whole is at a peak for the entire after-war period, with the euro -countries 2-3 percentage points above the average of non-euro countries.

Therefore, we have to look at the mindset of the present day’s generals: the mainstream economists. How could it be that they recommended governments to liberalize capital markets in the 1990s? Endorsed the setting up of a monetary union consisting of so apparently different countries? And when it all went wrong, they recommended austerity policies, which is a treatment quite similar to blood-letting an already weak patient. The generals should have known better by taking advantage of previous historical mistakes of which, one could point at the Gold Standard lasting only from 1925-31 (with a structure quite similar to the EMU) and the Wall Street Crash, 1929, (with many similarities to the 2008 Lehman Brothers collapse and aftermath) – history tells us, that inadequate monetary and financial arrangements often cause (perhaps unintended) consequences of rising unemployment, which can develop into political (and economic) nationalism. Why did the economists step back from telling about the past experiences?[2]

Anyway, I have to be cautious when I use the term ‘economists’ unconditionally. Because economists are not just one homogeneous group. If anywhere, we should be aware of Cambridge, where economists are famous for having an independent mind. I will be back on the distinct Cambridge Tradition in economics; but just to give you a few names: Maynard Keynes, Joan Robinson and the late Frank Hahn, who was a fellow of this college. Keynes is, in fact, known for having more than one opinion, and for good reasons, because economics is not an exact science. It is a human, or – to use Keynes’s expression – a moral science. Perhaps I should have said it was a human science, because I have my doubts with regard to the present day’s generals, for they think of economics as an exact and indisputable science when they deploy their mathematical models.

Some characteristics of Mainstream Macroeconomics

In any case, when we turn our attention to the Continental economists, they seem to be more single-minded. Here, economists close to governments or to Bruxelles share to a larger extent a common mind-set – the neoclassical way of thinking, which in Germany is called Ordo-liberalismus. Probably you know that ‘Ordo’ is an abbreviation for ‘Ordnung’ – in the sense that the market economic system is assumed to work the best, when it is controlled by competition, and government works the best, when it is small and required by law to balance the public budget.[3]

The fundamental assumption undertaken by these mainstream economists is that a private and competitive market system can always equilibrate demand and supply, if prices and wages are made fully flexible. Of course, the easiest example to explain, what ordo-liberal economists have in mind, is by using the strawberry market as a metaphor. We all know from personal experience that at the end of the day the seller is prepared to accept any low price – just to be sure that his desk is cleared with no unsold strawberries left, which have no value the next day. The price is considered as the effective clearing mechanism by mainstream economists. So, if all markets were organized this way and had a size of a local market place, where sellers and buyers can easily look over the trading, then a generalized strawberry model might work well. Hence, the macroeconomic model of most mainstream economists does look like an expanded strawberry model with hundreds of clearing markets, where demand equals supply, and prices and wage levels are made fully flexible.

For instance, in any mainstream textbook on macroeconomics, you will find the labour market presented as though it could be analysed like such a strawberry market, where wage flexibility secures that the market does clear. Therefore, mainstream economists give one and only one answer to the question, of how to reduce unemployment:

Conclusion (1): lower wages reduce unemployment. You hear this advice over and over again, and the logic seems crystal clear: when the price of a good falls, it is more easy to sell a larger quantity; this analytical outcome mainstream macroeconomists have taken uncritically from the microeconomic theory of the strawberry market.

Unfortunately for the mainstream economists and for those who follow their advices, it can easily be recognized that a labour market is nothing like a strawberry market – for many reasons.

Let us look a little closer at the macroeconomic arguments related to the adjustment of the demand for labour when the wage level is reduced. We have to take into consideration what happens to the economy as a whole, not only the labour market, because there will be spill-over effects, when wages are reduced. Wage-earners lose purchasing power – so they buy fewer goods than previously. If, for instance, a 10 percent wage cut is forced upon all wage earners, fewer goods will be sold and production will fall accordingly and so will employment. Even in an extreme case, where all prices also fell by 10 percent – then we have a case with unchanged purchasing power, where firms do not expect to increase output. But many prices, for instance house rents, instalments on loans, and imported goods, are fixed. Hence, lower wage means reduced demand and production. This is one of the explanations behind the deep recession which Europe is going through these days, and recommended by the modern ‘generals’ as a necessary remedy to re-start the growth process. Often, it is at this point argued that lower production cost would improve the country’s international competitiveness – and by that increase export, which might be correct for a single country, but not for Europe as a whole, which comes close to a closed economic system with rather little export. I will be back on this European fallacy of composition.

Let us look at one more dominating mainstream Conclusion (2), which says that austerity policy is necessary to secure budget balance and to stabilize the public debt/GDP ratio. The public debt is considered as a problem of major concern and balancing the public budget is considered as a prerequisite for this purpose by: 1. stabilizing the debt/GDP ratio and 2. to prevent politicians to intervene and by that to disturb the equilibrating market process going on within the private sector, which is considered self-adjusting. The public sector budget deficit is considered as a policy-induced impediment chocking the private sector’s ability to start growing. Demand management policy is argued to hamper the adjustment process within the private sector by reducing the downward pressure on wages and keeping rates of interest too high (crowding out).

Hence, the mainstream economists’ advice is that a credible economic policy has to correct the existing budget deficits by austerity measures. An expansionary policy would in that case only at the best prolong the period with high unemployment, but more likely make the situation even worse. This conclusion is derived from, what I have called the mainstream ‘strawberry model’, and a simplistic house-keeping budget model, where a perfect and self-adjusting market system together with the argument ‘that you should not spend more then you earn’ are the underlying assumptions, which makes it easy to characterize any argument in favour of an expansionary policy as irresponsible and not anchored in microeconomic theory.

Therefore, in this strawberry, house-keeping model, the best policy is – you guess – no policy, and a budget deficit, perhaps inherited from a former more casual government, has to be reduced by any responsible government, which sincerely wants to see the private sector start to grow sooner rather than later.

The finest hour of this mainstream way of thinking was back in 1995, when the American economist Robert Lucas was awarded the Nobel prize for having discovered – you guess again –‘policy ineffectiveness’ within this type of economic models. Robert Lucas in his 2003 presidential address to the American Economic Association declared that the “central problem of depression-prevention [has] been solved, for all practical purposes” and, further on, that Keynes’s General Theory should only be read by political scientists, if at all.

This brings me to the European question, why mainstream economists in general could be so wrong on the economic consequences of the Euro and austerity policies. The majority concluded that the European Monetary Union would enhance the growth potentials of the private sector by increasing competition, reducing transaction costs, removing exchange rate uncertainties and lowering rates of interest. These positive outcomes should be institutionalized by the creation of a politically independent European Central Bank (ECB). It was explicitly mentioned in the Maastricht Treaty that the board of the European Central Bank was not allowed to take any counselling from the European politicians, and decisions taken by the ECB should primarily be directed towards price stability (app. 2 per cent increase in consumer prices). Furthermore, the European so-called Stability Pact (strengthen by the Fiscal Compact), which is a part of the EU/EMU set-up, was deliberately intended to prevent the national politicians undertaking expansionary fiscal policy – recall the conclusion concerning policy ineffectiveness. Furthermore, the EU-commission was entitled to ‘advice’ and in the end to fine governments, which run excessive deficits without taking deliberate actions to reduce it.

This way of thinking on macroeconomics and economic policy is mainstream by the European elite, orchestrated by the teaching at prestigious Economics Departments via national civil servants, central bankers and EU-Commission and communicated to the public by the media. This way of thinking macroeconomics dominates textbooks; it is repeatedly expressed as the only and therefore scientifically correct opinion, of course absolutely free and independent of any ideology – being right or left, because Economics has got a status as an objective science, which cannot be disputed – like astronomy. Policy conclusions are presented as scientific facts: that the economic crises can be overcome by more wage-flexibility to reduce unemployment, by austerity policy to balance the public budget, and by a fiscal union in Europe with strict rules to save the euro. More market, less politics – listen to the economists, because they should and do know!

Mainstream macroeconomists disregard the methodological consequences of the ‘Fallacy of Composition’

The most interesting recent developments in macroeconomic theory seem to me describable as the reincorporation of aggregative problems such as inflation and the business cycle within the general framework of ‘microeconomic’ theory. If these developments succeed, the term ‘macroeconomics’ will simply disappear from use and the modifier ‘micro’ will become superfluous. We will simply speak, as did Smith, Ricardo, Marshall and Walras, of economic theory. (Lucas, 1987: 107-8)

As already mentioned, Robert Lucas (a neoclassical economist) made an apparent methodological brainwave when in the 1970’s he launched the hypothesis of rational expectation formation. The hypothesis is based on the assumption that we basically know very little about the agents’ expectation formation, but if they are rational, then they will learn from their mistakes. Why not, as a consequence of this learning process, making the assumption that economic agents do not make any systematic mistakes and that they individually optimise their economic behaviour on this basis? For, as Lucas argued, if the agents actually had this knowledge and did not use it in full, then it would be a case of irrational behaviour. At this point in the theoretical presentation it is often added that it might be the case that the agents do not have full knowledge of the future, but they are assumed to learn from their stochastically made mistakes, which will eventually give them the knowledge that is required for them to behave in accordance with the assumed full information. Ergo, the only microeconomic behaviour that is invariant in relation to the macroeconomic development is the assumption that the agents have correct expectations, which is the same as assuming that they know (the model-based) future.[4]

This has the logical consequence that the theoretically most relevant part of the analytical model will always be the position of general equilibrium (neoclassical theory), since here agents have realised their rational expectations. On the other hand, there might be some institutional obstacles to the smooth learning and adjustment processes which may delay even rational agents on their way towards the general equilibrium. Agents might know that due to transaction costs, insufficient information etc. there will be a kind of rational inertia in the adjustment process which takes some time to overcome, but as long as the agents’ preference structures are invariant to this inertia, agents will learn and the general equilibrium is still a highly relevant analytical point (new-Keynesians).

In the modern neoclassical analytical practice, ‘rational expectation formation’ is an indispensable, model-based precondition for ensuring consistency between the sum of the rational, individually decided actions, of the representative agent and the general equilibrium solution. In this case there is a model-based coincidence between the micro level and the macro level, which was also Lucas’s research ambition.

This requirement of a firm micro-foundation behind the behavioural relations of the representative agent on the macro level is by construction made look like a mirror of the behaviour of the microeconomic agent, under the assumption of full knowledge about all equilibrium values. Furthermore, perfect market-clearing is assumed on each market. Hence, outcome from partial market-clearing processes is made similar to general market-clearing.

Within this stylised neoclassical general equilibrium model:

- an exogenous change in the individual preference structure, e.g. an increased propensity to save will make the representative agent save more and, due to the perfect market-clearing mechanism, society will end up having increased its total savings and, accordingly, total real investment.

- a reduced labour market related social benefit will increase the representative agent’s supply of labour and, due to the perfect market-clearing assumption where ‘supply creates its own demand’, employment will have increased.

Within this kind of micro-founded neoclassical macroeconomic model where uncertainty is abandoned and a general equilibrium solution is axiomatically imposed, it will hardly make any sense to discuss whether the fallacy of composition can happen.[5]

The fallacy of composition as a consequence of methodological individualism and general equilibrium

Individual actions that are carried out by a large number of individuals can generate a socio-economic result, which is different from what would be expected on the basis of generalised microeconomic behaviour. (Dow, 1996:85)

…

[I]ndividual actions, if common to a large number of individuals, will generate an outcome different from what was intended by each. (Dow, 1996: 85)

There are two dominant possibilities of committing such a fallacy of composition when general equilibrium models are used as the analytical frame for understanding reality. An ideal model of individual behaviour and market adjustments are employed and cause ‘misplaced concreteness’, in the sense that the general equilibrium model is irrelevant especially in cases where unemployment is persistently high.

Firstly, when uncertainty prevails there is no representative macro-agent mirroring microeconomic assumptions. Individuals cannot know the future and therefore behave differently and seldom independently of one each other. Hence, the ‘representative agent’ in macroeconomics is a misleading analytical concept, which cannot be used to understand (not to speak about advising) how single macro-markets adjust, e.g. the labour market, not to speak of the economy as a whole.

Secondly, the fallacy of composition will be further re-enforced when a macroeconomic conclusion (relevant for the economy as a whole) is drawn on the basis of a single market analysis without taking interaction between several (all) macro-markets (labour, goods, housing, capital, money, credit and foreign exchange) into consideration. In general equilibrium models, the impact of the other markets is suppressed by the assumption of ‘all other markets unchanged’ – (ceteris paribus).

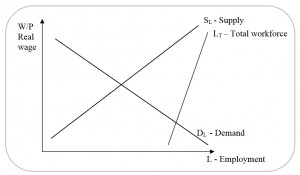

Both categories of fallacies of composition can be illustrated by the development in wage and employment in a traditional, neoclassical textbook presentation of the labour market.

To get rid of ‘voluntary’ unemployment is equally easy (in the figure). It is only a matter of increasing the individually determined labour supply (a representative agent). This is, according to neoclassical theory, done by lowering the social benefit or the income tax rate – pushing the SL-curve towards the right, so it comes closer to the LT-curve.

The fallacy of lower wage level increasing employment

This is, of course, well known from reality; but analytically you have to look at, at least, two markets at the very same time, labour and goods markets, to demonstrate this interdependency. We know the argument so well from Keynes’s multiplier analysis, which unfolds when unemployment is present; but dismissed in ‘modern’ textbooks as either only temporary (short term) or negligible because the private sector is assumed as self-adjusting.

You have seen this explanation of how to reduce unemployment and support economic growth over and over again; but it does not in this simple form give a relevant understanding of the macroeconomic dynamics. Because, wage is not just a cost to firms, it also represent an income and therefore purchasing power to households. When the wage (or social benefit) is reduced, disposable incomes of wage earners are reduced and, accordingly, there will be a tendency of lower private consumption, which makes firms cut their production (and employment).

The fallacy of export led growth solving the euro-crisis

If all countries did like Germany, they would all prosper and the imbalances of the EMU would vanish. But without a closed system – the euro has a floating exchange rate – the sum of the individual countries exports and imports has to be zero.

In a small open economy a third market (export and import of good and services) has to be integrated into the model. Usually, the foreign demand and foreign cost level are considered as exogenous variables. If so, there is a risk of committing one more fallacy of composition, because in case of international crisis, unemployment is rising also abroad, causing a downward pressure on wages commonplace in all countries, with no boost to export, but reducing the wage earners’ income all over Europe. Furthermore, if one country (e.g. Germany) is successful in promoting its export, then by book-keeping certainty import must go up somewhere else, which will cause further unemployment in this/these country(ies), hence reducing income, demand and wages even further (e.g. Southern Europe). The analytically relevant element, for the European economy, of this adjustment process requires that the economic development of the trading partners is not treated as exogenous, but will of cause respond to changed foreign conditions.

This import/export trade interrelationship within Europe (and especially within the euro-zone with no exchange rate adjustments) has until very recently been (nearly) disregarded by the Troika. Therefore, the negative impact of simultaneous, but unsynchronized fiscal contractions had a magnifying effect on the European economies considered as a whole. Year after year the euro-zone was underperforming and the public sector debt/GDP ratio continued to grow, because GDP fell in a number of countries and was even stagnant in countries with a strong competitive position.

The fallacy of reducing public debt creating growth

Look at a closed (no foreign trade) country or the euro-zone as a whole with balanced external trade. Here there has to be an identity connecting the public sector and the private sector balances. A deficit of the public sector has to be euro-by-euro matched by a private sector surplus.

This identity can be written:

- Sp – Ip ≡ G – Tax

Sp – private financial savings

Ip – private real investments

G – public sector expenditures (consumption and real investment)

Tax – taxes minus social benefit

A surplus in the private sector, i.e. financial savings exceeding real investment, has to be matched by an equivalent deficit in the public sector. As a starting point it is not possible to say whether a deficit (or surplus) at the public sector budget is caused by imbalances in the private or public sector. What is the cause and what is the effect. In modern times like for instance the post-2008 crisis the macroeconomic imbalances were mainly (but not solely) initiated by a fall in private real investment (house building as the outstanding example). Reduced private real investment caused unemployment to go up which had consequences for the public sector budget due to the automatic budget stabilizers (increased social benefit reduced taxes).

Let us take Germany as an example: Due to relative high unemployment in the 1990s and early 21st century, even Germany was unable to balance her public sector budget. We know the story how Germany as the very first country (together with France) broke the Stability Pact, which the Germans had been so eager to impose on the euro-members. Unemployment was above 10 percent in Germany, due to low private investments and high private savings i.e. low private sector demand. Hence, the so-called automatic labour market stabilisers de-stabilised the public sector budget. As mentioned above, the financial surplus in the private sector has to be mirrored by a public sector deficit and/or a foreign trade surplus (creating problems abroad). Hence, German public debt/GDP ratio was building up year by year and reached more than 80 percent in 2012.

Why did this rising German public debt ratio not cause financial turmoil or higher rates of interest? The answer is, simply, because the private sector had an even larger financial surplus/wealth looking for secure (and liquid) financial assets. (For a while German banks also bought Greek government bonds; but that trade stopped abruptly in 2008).

The bottom line: General equilibrium models cannot explain reality

In heterodox macroeconomics there are numerous examples of ‘fallacies of composition’, which is committed when general equilibrium models are the analytical framework, and representative agents with rational expectations and single market models are employed. This explains – at least part of – the disastrous counselling, which created a social catastrophe in Southern Europe and persistent stagnation in Northern Europe.

Previously, any academic critique of the mainstream/ordo-liberal way of thinking on economic policy was dismissed straight away – considered to be grounded either in political ideology, in anti-European sentiments or most likely in both.

But, the present and lasting crisis has challenged mainstream conclusions – at least to some extent. This challenge has not yet made an impression on the textbooks, but for sure on the media – take for instance, Martin Wolf in the Financial Times or Paul Krugman in the New York Times: once a week they have a comment where conventional wisdom is challenged always with reference to reality.

In fact, the ECB seems to be willing to disregard the recommendations from the German economists (and politicians) when it started the so-called QE-program of buying € 60 billions of government bonds each month for the following 1½ year. The ECB is doing it out of fear of falling prices, which cannot be explained within the general equilibrium model (GEM). Negative interest rates are another anomaly hard to analyse within the GEM.

Mario Draghi needs a heterodox macroeconomic model for judging the unorthodox monetary policy, which is undertaken (also) in Europe. Let’s hope that this policy at least partly for a while can make a counterweight to the continued austerity policy imposed by the major creditor nations in Europe. But, one should not be too optimistic, because the ECB is not looking at the unemployment figure – it is only price development which counts for the ECB. According to the EU-treaty, the ECB has only responsibility for price inflation, because the labour market is assumed to be self-adjusting.

References

Amoroso, B. & J. Jespersen (2014) Europa? Den udeblevne systemkritik, København: Politisk Revy

Andersen, Torben M. & Lars Haagen Pedersen (2005): Debat om fremtidens velfærd – opsamling og replik, Nationaløkonomisk Tidsskrift, vol. 143/nr. 2/november, p.275-298

Blyth, Mark (2013) Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, Oxford University Press

Jespersen, J. (2009) Macroeconomic Methodology, Edward Elgar

Jespersen, J. (2012) Euroen – hvorfor det gik galt og hvordan kommer vi videre, Allingåbro: forlaget DEO

Kahneman, Daniel (2003): Maps of bounded rationality: psychology for behavioural economics. American Economic Review, Vol. 93, issue 5.

Layard, Richard (2005): Happiness – lessons from a new science. London: Allan Lane.

Lucas, Robert E. (1987): Models of Business Cycles. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Lucas, R. (2004), Macroeconomic priorities, American Economic Review

Mankiw, G. (2010) Macroeconomics, 4th ed. New York: Worth Publishers

Keynes, J. M. (1936) The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, MacMillan

Rotheim, R. (2013) The Economist who took his model for a market, in J.Jespersen and M.O.Madsen (Eds), Teaching Post Keynesian Economics, Edward Elgar

Wolf, M. (2013) Germany is a weight on the World Economy, Financial Times, 6. November

Endnotes

[1] Parts of this paper has been given as a Churchill College-lecture in Cambridge, November 2013.

[2] Of course, I do not claim that history repeat itself; but on the other hand there are not reason to duplicate previous mistakes.

[3] In the UK and US this way of thinking economics comes close to monetarism.

[4] Newer economic behavioural research, however, has demonstrated that it is possible, by way of empirical experiments, partly to discover how individuals do react to altered external conditions. This research has actually revealed that individuals’ preference structures are not invariant with regard to changes in economic conditions and past experiences, see e.g. Kahneman (2003), Layard (2005).

[5] This is probably also, as mentioned before, the reason why Andersen & Haagen Petersen (2005) do not understand that the question about the fallacy of composition can be raised in connection with the use of the general equilibrium model DREAM, for, as they argue, all relevant interaction effects are built into the general equilibrium model. But they seem to disregard that the DREAM model, like many other applied general equilibrium models, by design is ‘well-behaved’ in the sense that it is given a priori the property of generating macro-outcomes which correspond to the microeconomic foundation. For instance, lower tax-rates and social benefit increase employment; an increased propensity to save increases capital formation etc.