Introduction*

The legal and political dispute Iceland fought with the UK and Dutch governments over responsibilities of deposits in the fallen cross-border Icesave Bank in wake of the international financial crisis – which hit Iceland severely hard in autumn 2008 when its three oversized international banks fell – not only revealed inhered weakness of the European financial system but also led to profound crisis of diplomacy during the Credit Crunch. The legal ambiguity of responsibilities was testing understandings and interpretations of international law in cross-border finance. Not fitting squarely within EU- diplomatic- or financial law it can be argued that the case in its process illustrates contested and hybrid construction of legality as here is explored. Rajkovic et al, (2016) understand international legality as interrelated processes of social and interpretive contestation in the construction of what is understood as (legal) rule in the world. In this regard the Icesave dispute illustrates how larger and more powerful countries were politically able to pressure a much smaller state in time of crisis into abiding to their own interpretation of law and in doing so rallying behind them support of international organizations like the EU and the IMF.

The Icesave dispute was thus not only a matter of international law, but rather also a case of contestation between cross border actors over determination of authority during the crisis. By empirically studying the Icesave dispute this paper discusses a profound crisis of diplomacy and the political processes of international legality of the financial sector during the Credit Crunch. This can be coined as case of perfect legal storm in international relations; a crisis of public international law, diplomatic law, EU law and finance law. This case study traces the dynamics of how international legality is produced and remade during the course of this particular inter-state crisis and in doing so thus contributes to analysis of political construction of international legality.

The study deals with interpretive contest in international relations on what is considered legal, in this particular instance dispute of responsibility over guarantying deposits of a fallen cross border bank. In this case intersecting practices and expertise were to revolve in a struggle over cross border insolvency law. By pressuring the Icelandic government into accepting responsibility of the fallen bank in UK and the Netherlands this was an international push towards sovereign socialization of private debt through twists of circumstances and practise.

At its core, perhaps, this is a study of struggle over who decides authoritative interpretations, of what in this particular instance is understood as international legality, which is constructed, construed and contested through multi-actor and multi-level interaction of multi-national relations.

The Crisis

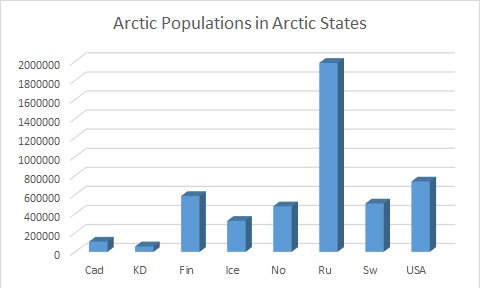

Iceland was the first victim of the of the global Credit Crunch when its three international banks came tumbling down in October 2008, amounting to one of the world’s greatest national financial crises. This was a financial tsunami without precedent. Glitnir Bank was the first to run into trouble when planned nationalization was announced on 29. September 2008. On the basis of emergency laws rushed through Parliament, Landsbanki was taken into administration On October 7th. The following day then British Prime Minister Gordon Brown invoked the UK Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (passed after ‘9/11’ in 2001) to freeze all Icelandic assets in the UK. Operating with little information and in a climate of confusion this was, he argued, to protect UK depositors in the bank. That act served as the final blow to Iceland’s last and largest bank still standing, Kaupthing. The vastly oversized Icelandic financial system was wiped out. Iceland is one of the smallest countries in the world and borders on being a microstate with just over 300,000 inhabitants. However, this experience ranks third in the history of the world’s greatest bankruptcies (Halldórsson & Zoega, 2010). Iceland also responded significantly differently to the troubles than most other states, allowing its financial system to default rather than throwing good money after bad.

Iceland had few good options. The IMF would not consider Iceland’s loan application until the dispute with the UK and Dutch governments over the Icesave deposits accounts was settled. The fallen Landsbanki had set up these deposit accounts in those countries, leaving many of their citizens without access to their money. Even though the Icelandic government steadfastly argued that it wasn’t legally at fault and that the state would fulfil all its legal obligations regarding Icesave, the IMF wouldn’t budge. Iceland was being pressured by the UK and Dutch governments, which were backed by the whole EU apparatus.

This was a staring contest Iceland could not afford to drag out as the state was running out of foreign currency. Early agreements in October and November 2008, first so-called Memorandum of Understanding with the Dutch government and then a more broad based Brussels Guidelines, which included EU involvement, were signed by Icelandic ministers in order for the IMF to be allowed to be brought in to stabilize the economy, not least through the introduction of capital controls and the co-funding of a loan package with the Nordic and Polish governments. By mid 2009, after change in government, these early agreements were abandoned for bilateral agreements with the finance ministries of the Netherlands and the UK, where Iceland accepted responsibilities for deposits of the fallen bank. In an extraordinary move the President, however, refused to sign the bills, referring them to referendums, in which they were rejected by large majority, spurring one of the greatest international disputes Iceland had ever fought.

Not only was Iceland denied any access to united efforts within Europe to bailout banks but the UK and the Netherlands were able use their position within the EU to pressure Iceland to accept their own interpretation of EU laws Iceland was to follow. Though ambiguity still remained as to who was legally liable for the loss, the UK government was using all means available to pressure Iceland to accept responsibility, as is documented later in this paper.

On 28 January 2013, the EFTA Court finally ruled on the case, concluding that no state guaranties were in place on the deposits and, thus, dismissing the claim of the British and Dutch authorities (Judgment of the Court, 2013). The ruling vindicated the Icelandic state of any wrongdoing. In early 2014 the Dutch and the Brits filed claim against only the privately held Icelandic Depositors Guaranty Fund before the District Court of Reykjavik.

A Systemic Flaw

The collapse of the Icelandic banks clearly revealed a serious weakness in the European banking passport system, a macroeconomic imbalance within the Single European Market. It was a weakness that some of the more established banking nations had warned against when the system was being constructed (for more, see Benediktsdottir, Danielsson, & Zoega, 2011). The main flaw lay in the fragmented nature of supervision on an otherwise common market – European-wide regulation but only state level supervision resulting in a tapestry of schemes and insurance levels across the EU. This had caused a mismatch between access to market and adequate supervision.

There was also an inhered flaw in the setup of Iceland’s link to the EU through the EEA agreement. Being in the Single European Market through the European Economic Area agreement (EEA) but outside the fence of EU institutions left Iceland without shelter when the crisis hit. This neither-in-nor-out arrangement – with one foot in the Single European Market, with all the obligations that entailed, and the other foot outside the EU institutions, and therefore without access to back-up from, for example, the European Central Bank – proved to be flawed when the country was faced with a crisis of this magnitude: The oversized Icelandic banks were operating in a market that included 500 million people but with a currency and a Central Bank that was backed up by only roughly 330,000 inhabitants. As a participant in the EU Single Market, Iceland was inside the European passport system so the banks were able to operate almost like domestic entities throughout the continent.

Landsbanki had in 2002 acquired the British Heritable Bank and in 2005 furthermore opened a separate subsidiary in London. However, when marketing the Icesave deposit accounts in October 2006 Landsbanki decided to bypass both and instead opened a branch from the Icelandic Landsbanki collecting the deposits. This was done to be able to transfer the money upstream to the mother company in Iceland (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 8), something the subsidiary system does not allow. Furthermore, branches were under general surveillance in the home country of the parent bank, while subsidiaries were subject to such monitoring in the host country. However, according to this setup, liquidity surveillance should have been in the hands of the British FSA, which also had authority to intervene in marketing of the deposit scheme in the UK. Interestingly, however, when setting up the accounts, Landsbanki had negotiated exemption from the FSA liquidity surveillance until 2011 – liquidity surveillance of Icesave was thus only in the hands of the mother company in Iceland.

At the time no one seemed to even contemplate the risk involved. Without any objections from either Icelandic or UK authorities, the bank quoted the EU/EEA Directive 94/19/EC on Depositors Guarantee Schemes, they insisted was in place in Iceland, which, they said, would protect all deposits up to €20,887. Then they referred to the British top up guaranty for the rest – British authorities were by then promising to cover up to 50.000 Pounds per account. This was however always very ambiguous.

Kaupthing opened a similar high-yielding Internet deposits scheme, named Kaupthing Edge. However, unlike Landsbanki with Icesave, Kaupthing used its subsidiary, Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander, to host the deposits. Edge deposits therefore had to be kept in the UK and were under British banking regime surveillance. At the time, few noticed the difference, which after The Crash left those involved in the two cases a world apart.

Playing on an Icelandic symbol, Icesave was marketed to tap into the trust associated with Nordic economies. Soon attracting the favourable attention of the financial media, the scheme became an instant success. The Sunday Times, for example, wrote enthusiastically about the scheme under the headline: ‘Icesave looks like a hot deal’ (Hussain, 2006). Before the end, Icesave had attracted almost as many savers as there were inhabitants in Iceland. Landsbanki had for a while enjoyed better ratings than the other two because it was able to tap into the Icesave deposits to keep liquidity flowing. This was, however, a mixed blessing, as reliance on deposits leaves a bank much more vulnerable to bad news than if it is funded in the wholesale market. Even a minor issue can result in a run on a bank with avalanche of withdrawals if it is portrayed in the wrong light. Still, all three banks were passing the Icelandic Financial Supervisory Authorities (FME) stress tests with flying colours. In theory, the banks were all doing well. Amongst those buying this story was the Financial Times, which as late as August 2008 wrote that ‘fears of a systemic financial crisis in Iceland have dissipated after the country’s three main banks announced second-quarter results showing that they are suffering amid the downturn – but not too badly’ (Ibson, 2008).

The Central Bank stretched itself to the limit to keep the banks liquid in domestic króna, for example accepting their own bonds as collateral – the so-called love letters. However, to back up the overinflated banking system in such dire straits it needed a sizable sum in foreign currency. The Central Bank thus went knocking on doors in the neighbouring countries asking to open similar swap lines as others were negotiating, that could be drawn on in time of need. This was meant to boost confidence in Iceland’s capacity to back up the financial system. To the surprise of the government, however, apart from earlier limited swap-lines with the Nordics, Iceland met with closed doors in most places. This was at a time when the neighbouring states were still upholding much more extensive currency swapping agreements.

Not only had the banks been pushed out of the international capital market, but the government had as well. For the international financial system tiny Iceland was as a state not thought to be too big to fail. Iceland first approached the Bank of England in March 2008 for a swap-line agreement. Initially, the request was positively received, but with a suggestion that the IMF would analyse the need. A month later, the climate had changed. It had become clear that the central banks of Europe, the US and the UK had collectively decided not to assist Iceland. Later it became known that the governor of the Bank of England, Mervin King, offered instead to co-ordinate a multinational effort to help scale down our financial system. His offer was instantly turned down by the leading governor of the Icelandic Central Bank, Mr. Davíð Oddsson (See for example, Wade & Sigurgeirsdottir, 2010.

UK Concerns

When Northern Rock was running into trouble in late 2007 and taken into receivership in February 2008 worries over further volatility in the banking system were spreading in the UK, raising concerns of health of many other banks. By 2008 Landsbanki had collected around 4 billion pounds through the Icesave scheme. With the International Financial Crisis now blazing and the apparent wide exposure of Iceland’s oversized banking system this was causing increasing concerns in the UK, especially because of the poor state of the Icelandic Depositors Guaranty Fund holding only around 1 per cent of the liabilities of the Icelandic banks now facing headwind (Jónsson, 2009). This caused an avalanche of negative reporting in the UK media on the Icelandic banks. On 5th February 2008 The Daily Telegraph for example asked in a headline: “Is Iceland headed for meltdown?”(“Is Iceland headed for meltdown?,” 2008). Subsequently increased withdrawals were almost amounting to a run on the bank, which the bank was barely able to withstand, before deposits started picking up again in April.

These events lead the British FSA to push for restructuring of the online branch, for example proposing revoking an exemption Icesave had negotiated from liquidity surveillance in the UK. This was raised in meetings between governors of the Icelandic Central Bank and the Bank of England on 3d March 2008 and again in meeting the FSA had with Landsbanki management on 14th March 2008. In these meetings the FSA furthermore proposed moving the deposits to Landsbanki’s Heritable subsidiary and thus entirely under jurisdiction of the British Financial Services Compensation Scheme (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 12, 13). For this, however, demands were made that assets had to follow from the parent bank in Iceland to the UK, which Landsbanki had trouble meeting (Ibid). The liability amounted to half Iceland’s GDP. Additionally such transfer would have to be with depositors consent, though force majeure situation might justify a quicker move. This was the start of increased tension between Iceland and the UK over the Icesave deposits, ultimately resulting in the UK authorities seizing the bank in October 2008 when the parent bank was falling in Iceland.

The tension was heightening in frequent exchange of letters over the coming weeks and months. In a letter dated 29th May 2008 the FSA finally revoked the exemption from UK liquidity surveillance and subsequently demanded that the Icesave deposits be moved to subsidiary (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 16). The FSA had concerns that neither the Icelandic Guaranty Fund nor the Central Bank had ability to back up the bank in times of crisis. The FSA also asked that the Icesave deposits would be capped at 5 billion pounds level which they were now reaching close to and that interests would be set below featuring on best buy tables (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 17). Landsbanki replied on 15th July 2008 agreeing with the general aim of moving the deposits to subsidiary but refusing both capping the deposits and the request of setting interest below best buy level. In the meantime the issue had been reported widely in the UK, for example discussed in the House of Commons were MPs quoted report in The Times on 5th July stating that collectively the deposits of the Icelandic banks in the UK were amounting to 13,6 Pounds or “twice the country’s entire GDP” (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 19).

On July 22nd 2008 the FSA wrote back saying that Landsbanki’s reply was worrying, that risk of run on the bank was increasing and that the FSA would be forced to consider applying its legal measures against the bank if its requests were not being met. That is; a solid cap, solid liquidity buffer and firm time tabled intention of subsidiarisation. (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 19). Though Landsbanki voiced willingness to comply in its letter to the FSA on 28th July it also explained why it might have difficulties in implementing what was being requested unless the FSA would agree on flexibility regarding some of its conditions in the transition period. On these conditions Landsbanki and the FSA were never able to agree on. While the FSA was operating in order to protect UK based depositors the Landsbanki management was rather concerned with saving the mother bank in Iceland. These aims proved contradictory and caused prolonged frictions (see SIC 2010, Vol 6.).

The FSA was not only applying its pressure in letters and meetings with Landsbanki but also in ongoing correspondence with the Icelandic FME and Central Bank. In a letter to Landbanki on August 5th 2008 the British FSA demanded Landsbanki to confirm within a week how the bank would comply with conditions set by the FSA in order to move the Icesave deposits to its subsidiary in London, otherwise it might be forced to apply its formal legal measures (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 23). This was the second time the FSA threatened in a letter to directly intervene in the bank’s operations.

The Icelandic Central Bank was now directly involved. Reportedly it considered openly defying the FSA but decided against that approach as it might risk the stability of the entire Icelandic financial system (SIC 2010, Vol 6). On 11th August 2008 the Icelandic FME wrote back to the FSA pleading on behalf of Landsbanki for flexibility while transferring Icesave to the Heritable Bank in London. The two surveillance authorities talked in a teleconference a week later where the FSA suggested that Landsbanki might sell Icesave. In the meantime, the FSA had written Landsbanki once more on 15th August 2008, demanding increasing reserves to 20 per cent of deposits. At the end of the letter the FSA threatened for the third time that it might apply its formal authoritative legal measures against the bank and stop deposit collection into Icesave accounts (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 25). The Icelandic actors, that is, the Landsbanki, the Icelandic FME and the Central Bank however believed that would only trigger liquidity crisis – not only for Landsbanki but for all Icelandic banks and indeed also the UK fragile banking system (SIC 2010, Vol 6).

It was now clear that the British FSA considered Landsbanki being in non-compliance with its conditions and that it was already failing. The Landsbanki management pleaded with the Icelandic Minister of Commerce to intervene, who with a team of officials met with UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling in London on 2nd September 2008. Mr. Darling has since reported that he was disappointed with the Icelanders as he felt they did not appreciate the seriousness of the situation (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 31, 229). Following up on the meeting few days later, leading official in the British Treasury dealing with the Icelandic case, Clive Maxwell, called the Icelandic Ambassador in London, expressing the Chancellors concerns and explaining how politically difficult the relationship with Iceland had become in the UK. This was perhaps a warning that tougher measure might be taken against Iceland.

In a letter on 3d September 2008 the FSA once again wrote to Landsbanki saying it was considering applying its formal legal measures if the bank would not before 8th September 2008 explain how it would comply with the conditions. Before the deadline Landsbanki replied by again voicing willingness to comply but explaining why it might be difficult to meet all the requests. In wake of several subsequent meetings and correspondence between agencies in the two countries the FSA wrote back on 17th August 2008 announcing that it would apply its legal measures. It was now ordering the bank to fully comply with bringing assets to the UK to underpin withdrawals from Icesave accounts and in order for them being transferred into the British financial space (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 33). The state of the international financial system had by then gone from bad to worse when Lehman Brothers collapsed in the US on 15th September 2008.

In a desperate reply on 19th September 2008 Landsbanki indicated that it would comply before turning straight to the Icelandic FME asking for help. The two surveillance authorities were still in correspondence on the issue when further trouble arose for the Icelandic banks, which I turn to next.

Heightening Pressure

When a planned nationalization of one of the three banks, Glitnir, was announced in Reykjavik on Monday September 29th depositors were flocking to nearest branch and withdrawing their savings. When the news travelled abroad, many of the 300,000 Icesave depositors in the UK, also rushed online to withdraw their money from the Icesave accounts. Throughout the continent, central banks and governments were harmonizing their response to the crisis. The ECB and the Bank of England, for example, were providing massive liquidity to European banks, but despite a wide-ranging emergency plea, Iceland would not be allowed access to these funds. The same was also to become true in Washington. Iceland was flatly refused as neighbouring governments collectively opposed a bailout, referring it instead to the IMF. Being the first Western country in four decades to surrender to the IMF was seen as a humiliation and a defeat for the Icelandic postcolonial project (see Bergmann 2014b).

In the UK, worries over the poor state of the Icelandic banks had been growing for some time. Since May, unsuccessful negotiations had been under way to move the Icesave deposits to Landsbanki’s Heritable Bank and thus under the cover of the UK banking scheme. On Friday 3d October the FSA formally announced applying its legal measures against Landsbanki stipulated in the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA). The bank was already by Monday to install funds amounting 20 per cent of the Icesave deposits into the Bank of England, lower free access deposits to below 1 billion pounds by end of 2008 and cap total deposits at below 5 billion pounds (SIC 2010, Vol 6). The bank was also to bring its interest below best buy levels and halt all marketing of free access deposits. As Landsbanki did not at the time have funding available to comply this was in effect equal to killing of the bank.

In the evening Alistair Darling called his counterpart raising concerns that 600 million pounds were illegally being moved out of Kaupthing and back to Iceland. To this the Icelandic authorities had no answer. By close of market the same day The European Central Bank had placed a margin call of 400 million Euros on Landsbanki in Luxembourg, threatening to seize many of its assets. However, on Sunday evening the ESB revoked the call and by doing so releasing some of the tension (SIC 2010, Vol 6).

Thus, while Iceland was desperately trotting the globe shopping for money, the UK authorities and the ECB were not only refusing any funding but indeed pressing it for cash. The firm stand of the Bank of England, the ECB and the US Federal Reserve against Iceland also made the Scandinavian neighbours hesitant to help further (SIC 2010, Vol 6). To stem the bleeding of the Edge and Icesave accounts, both Kaupthing and Landsbanki were frantically selling off assets at rock bottom prices. With the rapidly increasing flow of negative reporting abroad, the run on Icesave in the UK grew stronger. On Saturday 4th October, depositors could no longer access their accounts online. On the website an explanatory note read that this was because of technical problems. Traffic had increased more than fivefold. Really, however, this was not least because the bank was already exhausted by the run; it could no longer honour the withdrawals. Out of the £4.7 billion the 300,000 or so depositors held, more than £300 million ran off the accounts on that day alone. Foreign reporters and government authorities responded by asking whether Iceland would provide the same protection to foreign depositors as it had already announced for domestic ones. Pressure rose when the government struggled to find a diplomatic answer (Jóhannesson, 2014).

Around dinnertime on Sunday 5th October British PM Gordon Brown called his Icelandic counterpart Geir Haarde, urging him to seek IMF assistance. They were old acquaintances, since both had served for years as finance ministers, meeting on several occasions. Brown also voiced concern that money amounting to more than one-and-a-half billion pounds was unlawfully being brought over to Reykjavik out of Kaupthing’s London subsidiary, Singer & Friedlander, which would not be tolerated. The amount had thus grown by billion pounds in only couple of days since the call from Darling (see SIC 2010, Vol 7).

This claim of illegal money transferring out of the UK, which was repeated by many UK officials over these dramatic days, later proved unfounded as was for example stated in report to the House of Commons Treasury committee (2009, April). The UK was in this regard already burned by Lehman Brothers, which prior to its default had sneaked back to the US eight billion dollars from the City of London, and would not allow the same thing to happen again. The call ended without a solution, with Brown all but begging Haarde to call in the IMF rescue team. The message from the UK side in frequent correspondence over the weekend was always the same: no bailout money would be available internationally for Iceland except through an IMF programme (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 20: 100).

The UK authorities were threating to seize Icesave already by Monday. To halt the blow the FSA demanded 200 million pounds immediately to underpin Icesave and further 53 million to stabilize the Heritable Bank (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 145). All attempts to shift the Icesave accounts into British banking space had thus failed. Negotiations with the British FSA to allow Landsbanki to move the deposits to its London Heritable Bank and thus under the UK banking regime were stuck. The British were asking for more money alongside it than either Landsbanki or indeed the Icelandic state could possibly raise. The Icelandic Central Bank could only bailout one of the three big Icelandic banks. All of them seemed to need around 500 million Euros for only short-term rescue. When it came clear that Kaupthing would win the lottery of which to bail out, as it was deemed to have the best chance of surviving, the light was finally out on Landsbanki.

God Bless Iceland!

When the markets opened on Monday October 6th, the FME had stopped trading the banks’ stocks and the banks themselves froze all fund transactions. To counter the almost inevitable avalanche of withdrawals, the government issued a blanket protection for all deposits within the country. The UK and Netherlands were issuing top-up guarantees for deposits above the €20,887 stipulated in Directive 94/19/EC up to €40,000 in the Netherlands and, by Wednesday, up to £50,000 in the UK. Many European states were also issuing complete guarantees, including Ireland, Germany, Denmark and Austria. Iceland was, however, only guaranteeing domestic deposits but could not explicitly state what would happen in foreign branches, apart from a vague general pledge to the effect that the banks’ Depositors and Investors Guarantee Fund would be ‘supported’. That promise was always very ambiguous and, furthermore, it was always clear that it might anyway be difficult uphold, as deposits in foreign branches of Icelandic banks, most of which were on Icesave accounts, amounted to around £8.5 billion, about 80 per cent of the country’s GDP, whereas the fund held only about 1 per cent of that total amount, which, though, was comparable to other countries. The ambiguity of the statements coming out of Reykjavik was thus worrying neighbours, especially government officials in Whitehall (see Jóhannesson, 2014).

It was clear that Landsbanki would already be defaulting the following day. This was a stark reversal of the bank’s situation from just a few months before, when it seemed to be well funded with a comfortable €800 million liquidity and strong inflow of foreign deposits. Furthermore, redemption of loans was low until late 2009. And even though it was exhausted of foreign cash by the run in the UK, the bank still had enough money in Icelandic króna to survive this storm; the problem was that the króna was no longer tradable for foreign currency. This was thus a double crisis – a banking crisis and a currency crisis – starting already in March (see Bergmann, 2014).

Around noon Monday 6 the UK embassy in Reykjavik reported to London on events over the weekend. Interestingly the ambassador mentioned the Icelandic governments guaranty of domestic deposits but then indicates that the government had sent similar statement to London because of Kaupthing and Landsbankis operations in the UK (Jóhannesson, 2014). This was a misunderstanding but it seems clear that the UK government believed that such a promise had been given, that the Icelandic government would at least protect the minimum of EUR 20.887 (ibid). This proved to be a wrong interpretation of what Icelandic officials meant when stating that the Icelandic Depositors Guaranty Fund would be ‘supported’ (ibid), but given the fact that Iceland officials at the time were avoiding contact with the British and only providing them with as vague responses as possible (ibid) one can understand that there was wide room for such misunderstandings.

In the afternoon on Monday 6 October the Icesave bank was being closed in the UK by formal issue of the FSA. Around the same time PM Geir Haarde was announcing that the Icelandic state would not have the means to bail out the banks. By trying so it ran a risk of being sucked with them into an economic abyss. (Haarde, 2008). An emergency legislation was rushed through parliament, allowing the government to split the banks into a domestic only good bank surviving and bad bank taken into receivership. This method was according to advice of a financial specialist, Marc Dobler, sent from the Bank of England to Reykjavik (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 120). The legislation also altered the order of payments of claims out of the fallen banks by moving depositor’s claims to the front. This was a force majeure situation. The government simultaneously wanted to protect domestic depositors in Iceland and the state from claims from abroad. The action was part of the defensive wall being raised around ordinary households. Foreign creditors would simply have to accept losing most of what they had loaned to the Icelandic banks.

This was a time of chaos. UK authorities were desperately trying to get information out of Iceland. It didn’t help when Alistair Darling could get through to neither the Icelandic PM nor the Finance Minister, who he was asked to contact again the following morning. The UK government’s frustration was reported in correspondence throughout the evening by the UK ambassador with Sturla Sigurjónsson of the Icelandic Prime Ministry. He reported a message from London: if convincing explanations would not come out of Reykjavik, that would be negatively interpreted in London and might have serious effect on the bilateral relationship between the two countries. (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 147).

Before opening of business on Tuesday morning, a board for a new Landsbanki had been appointed. Meanwhile, in the UK, the FSA issued a moratorium on Landsbanki’s London based Heritable Bank.

With all funding opportunities closed, the situation was growing bleaker by the hour. As planned Alistair Darling called on Tuesday morning to discuss these and other grave matters with Finance Minister Árni Mathiesen. When he could not get a clear state guarantee out of his Icelandic counterpart, an assurance that UK depositors would be protected, at least up to €20,887 according to Directive 94/19/EC, he stated that this would be ‘extremely damaging to Iceland in the future’ and then ended the call saying, ‘the reputation of your country is going to be terrible’ (“Samtal Árna og Darlings,” 2008). Mathiesen could not but agree, but he understood from their conversation that he would still have some time to work things out.[1]

Invoking Anti-Terrorist Act

Seen from the UK and the Netherlands, the situation was simply that Icesave depositors were left without access to their accounts. The website was inaccessible and no trace of the bank was left in the UK or the Netherlands. No one answered the phone and there was not even an address to go to. Depositors were in an intolerable position – the bank had disappeared without a trace from the face of the earth. This caused a seriously strained relationship Reykjavik had with London and The Hague. The British and the Dutch governments decided to compensate their depositors, even beyond the €20,887 mark guaranteed by Directive 94/19/EC. For this they demanded payback with interest from the Icelandic government.

In Whitehall, preparations had been under way for dealing with the Icelandic crisis. Icelanders would not get away with simply cutting off their foreign debt, shutting the doors and leaving British citizens out in the cold. It did not help that UK officials had learned of the message from governor of Iceland’s Central Bank on TV few days earlier, in which he stated that foreigners could only expect between 5 to 15 per cent of their claims. The plan was to be kicked into action. The British claimed that giving preference to depositors in domestic banks over those in foreign branches was a breach of European regulations, which Iceland subscribed to through the EEA.

In the early morning of Wednesday 8th October 2008 Alistair Darling appeared on BBC Radio 4 claiming that the Icelandic government was reneging on its responsibility to UK depositors, and that this would not be tolerated. Referring to his conversation with Iceland’s finance minister Mathiesen the day before he said: ‘The Icelandic government, believe it or not, told me yesterday they have no intention of honouring their obligations here’ (Darling, 2008). In a joint press conference at 9:15 Darling and Gordon Brown announced a massive bailout of UK-based banks, to the tune of £500 billion. As a result of pumping the money into the banks, the British state acquired a majority stake in the Royal Bank of Scotland and steered the merger of HBOS and Lloyds TSB, in which the state had acquired third of the shares. There was, however, not a penny for Icelandic-owned banks in the UK. On the contrary, Brown claimed that Iceland’s authorities must assume responsibility for the failed banks and announced that the UK government had taken ‘legal action against the Icelandic authorities to recover the money lost to people who deposited in UK branches of its banks’ (quoted in Balakrishnan, 2008). Director of the British FSA, Hector Sants, is reported to have told the management of Kaupthing Singer and Friedlander in the UK: ‘Those funds are not for you’ (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 171).

Earlier in the morning, the UK FSA had called Kaupthing demanding £300 million instantly be moved from Reykjavik to Singer & Friedlander to meet the run on Edge accounts, which with the Icesave website down also was blazing, and then a further £2 billion over ten days. This was an impossible demand for Kaupthing to meet, and it instead called the Deutsche Bank, asking it to sell off Kaupthing’s operations in the UK. Deutsche’s brokers thought that could be done within 24 hours (Jónsson, 2009).

The legal actions Brown had mentioned in his press brief, however, went much further. At 10:10 in the morning, deposits in Landsbanki’s Heritable Bank were moved to the Dutch internet bank ING Direct for free when the ‘Landsbanki Freezing Order 2008’ took effect (The Landsbanki Freezing Order 2008, 2008). The action was based on the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act, which had been put in place after the terrorist attacks in the US on 11 September 2001. Not minding that around a hundred thousand people worked for Icelandic-held companies in Britain, the UK government invoked the Anti-Terrorism Act to freeze the assets of Landsbanki in the UK and for a while also all assets of the Icelandic state including the Icelandic government, the Icelandic Financial Surveillance Authority and the Icelandic Central Bank (SIC 2010, Vol. 6, Ch. 18: 40).

Later that day the FSA took control of the Heritable Bank and Landsbanki’s subsidiary in London. The Landsbanki Freezing Order was issued with an explanation reading:

The Icelandic authorities have announced that Landsbanki has been placed into receivership but has not given any indication as to how overseas creditors will be dealt with. The Icelandic Government has also announced a guarantee of all depositors in Icelandic branches. However, overseas depositors have not been covered by the guarantee. This exclusion on grounds of nationality is discriminatory and unlawful under the rules governing the European Economic Area. The UK government is taking action to ensure that Landsbanki assets are not transferred from the UK until the position of UK creditors becomes clearer. The UK authorities are seeking to work constructively with the Icelandic authorities to ensure speedy resolution.

Subsequently, Landsbanki and for a while also Iceland’s Central Bank and Ministry of Finance was listed on the Treasuries home page alongside other sanctioned terrorist regimes, including Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, Burma, Zimbabwe and North Korea.

While Kaupthing’s CEO, Sigurður Einarsson, was in his London office in the late morning discussing with Deutsche Bank over the phone the fastest way to liquidate its assets, he read a banner running on the TV screen saying that the FSA had already moved Kaupthing’s Edge accounts to ING Direct in the Netherlands. Their phone conversation quickly ended, as there was no longer anything to talk about. In the afternoon, the UK authorities issued a moratorium on Singer & Friedlander, showed its Icelandic CEO, Ármann Thorvaldsson, the door and sealed the offices (Thorvaldsson, 2009). This instantly prompted a flow of margin calls and a further run on the mother company. When the dark set in, Kaupthing Bank was itself taken into administration in Reykjavik. Thirty thousand shareholders lost all their investment. Interestingly, both the previously mentioned report to the House of Commons Treasury committee (2009, April) and also the British FSA later found out that no money had illegally been moved from Singer & Friedlander to Iceland (Júlíusson, 2009), which, however, had been one of the main justifications for the UK’s attack on Iceland.

On this same day, Thursday 9th October, Brown told BBC that the actions of the Icelandic government were effectively illegal and completely unacceptable. ‘They have failed not only the people of Iceland; they have failed people in Britain’ he said. Then he said his government was ‘freezing the assets of Icelandic companies in the United Kingdom where we can. We will take further action against the Icelandic authorities wherever that is necessary to recover money’ (quoted in “Brown condems,” 2008). Later that day, Brown told Sky News that Iceland, as a state, was bankrupt and that the ‘responsibility lies fairly and squarely with the Icelandic authorities, and they have a duty in my view to meet the obligations that they owe to citizens who have invested from Britain in Icelandic banks’ (“Brown Blasts Iceland Over Banks,” 2008). Iceland was being completely rebuffed. In fact, in the coming days Brown’s rhetoric against Iceland was only to harden.

With UK depositors holding a stake of £700 million in Icesave, including many charities’ funding, Brown stated that the Icelandic authorities were now responsible for the deposits. Even in the UK, many were stunned by Brown’s harsh response to the Icelandic crisis. Many claimed that by attacking Iceland, a foreign actor, Brown was attempting to divert attention from difficulties at home, perhaps much as Margaret Thatcher had done during the Falklands crisis (Murphy, 2008). Initially it did indeed work. On its front page the Daily Mail declared ‘Cold War’ (2008) on Iceland and the Daily Telegraph screamed across its front page: ‘Give us our money back’ (2008). And these were papers that did not even support Brown or his Labour Party.

With access to the estimated 7 billion pounds the Icelandic government and banks held in assets in the UK no longer being available, the wall finally came tumbling down. Invoking Anti-Terrorist legislation against a neighbouring state and fellow NATO and EEA member was virtually an act of war, as is indicated in the interviews conducted for this paper. This was an unprecedented move against a friendly state, which cost Iceland dearly, in both economic and political terms. Moody’s instantly downgraded Iceland by three full points, to A1. Money transactions to Iceland were stopped not only in the UK but as a result also widely in Europe, where many banks refused to trade with Iceland after it had been listed in the UK with terrorist actors. The payment and clearing system for foreign goods collapsed. In only two days, all trading in króna had ceased outside Iceland’s borders (SIC 2010, Vol. 7).

By Thursday 9 October 2008, almost the entire Icelandic financial system had collapsed in a dramatic chain of events, which later became known simply as The Crash. Ironically, this was a full week before Glitnir’s 15 October deadline – which had started the whole thing.

Explaining the UK Attack

In hindsight it seems clear that the UK authorities went in their actions much further than needed in protecting British interests. Invoking the Anti Terrorist Act was for example in stark contrast to responses elsewhere. Authorities in the Netherlands, for example, saw no reason to freeze assets and in Stockholm the Swedish Central Bank was still trading with Kaupthing’s Swedish branch. In this segment I attempt explaining some of the reasons behind the harsh response of the UK government against Iceland.

First thing to note is that this was a time of utter chaos, frustration and widespread political as well as economical upheaval. Perhaps part of the reason can be found in the fact that Iceland’s economic fragility turned the mirror on the UK and its own volatile financial situation. Economist Willem Buiter (2008) who had studied the state of the economy in both countries, saw the similarity and wrote that it was no great exaggeration to also describe the UK as a huge hedge fund.

From private off-the-record interviews I conducted for this paper in late 2013 and early 2014 with several leading UK officials, within for example the UK Treasury, Foreign Office and the Labour Party, who were at the heart of these events at the time, it seems clear that the UK government finally lost faith in not only the Icelandic banks but also the Icelandic government over the weekend from Friday 3d to Sunday 5th October, 2008. This conclusion is for example also supported in unpublished report Icelandic stakeholders commissioned a leading business investigation firm in London to conduct into the issue.[2] The report states that the UK government believed until October 3d 2008 that a ‘high level political deal’ was in place of fast-tracking Icesave deposits to British banking space. The alleged deal included stipulation of insurance premium to be paid by the Icelandic government, that the ‘Icelandic government [was] to transfer 200 million pounds to the UK’.

How the UK authorities came to believe this deal was in place is not clear as no such understanding is sheared amongst Icelandic officials at the forefront of these events at the time, who also were interviewed off the record for this paper in late 2013 and early 2014. Neither are there any public documents available to support such alleged ‘deal’ at ‘high political level’ as the report claims.

UK officials interviewed for this paper point out that this was a time of great uncertainty and misinformation. Long lasting still ongoing tension at the time between the British Foreign Office (FCO) and the Treasury had weakened British institutions. Under Gordon Browns premiership it is reported that the Treasury was leading all actions against Iceland and that the FCO was hardly involved. Still, the little information that was available on Icelandic politics within the UK government was kept at the FCO. It is furthermore reported in the interviews I conducted that there was a serious communication malfunction between the Treasury, the FSA and the Bank of England. This was unfortunate as reliable intelligence on the Icelandic banks was rather within FSA and the Bank of England than in the Treasury.

In addition to not understanding Iceland, the Treasury was overworked by challenges of the international financial crisis blazing at the time. It is furthermore reported that as relatively young and small ministry in the UK the Treasury was suffering from high staff turnover and thus lack of institutional memory. All of this combined meant that when dealing with little Iceland the Treasury neither had the means nor knowledge to properly contemplate the highly complex situation.

My interviewees concur in saying that when trouble arose Iceland was thus not in focus in the Treasury, in fact it was rather viewed as troubling black hole preventing the UK from dealing with the big picture. Unlike the Foreign Service the Treasury had no room to contemplate political implications cross borders, in dealing with Iceland this was just a financial issue like all others. ‘This was just nuts and bolts finance’ said one of this papers interviewees. While desk officers were of course analysing Icelandic banks like all others, higher-level officials were ignorant about the country.

One interviewee for this paper, senior official in the British Foreign Service said that this was in effect a failure of diplomacy. He said that on both sides there existed surprising lack of understanding between the two governments, that the Icelanders did not know British governance and the UK side was almost utterly ignorant about Iceland. He pointed out that even though Gordon Brown and Geir Haarde were on good terms and for example met at Number 10 after Brown took office, that friendship did not amount to much at time of crisis. ‘To think so was foolish’, he said.

Plan A and Plan B

British officials interviewed for this paper pointed out that repeated references in FSA letters to Landsbanki to its legal authority to interfere with the banks operation in the UK, discussed earlier in this paper, was nothing short of blatant threat of seizing the bank. This warning seems, however, not to have been taken equally seriously in Iceland. According to British officials interviewed for this paper a low level and at first rather vague plan to deal with Iceland was slowly starting to emerge since May 2008, developing in gradual steps until the very end when the UK government finally struck on October 8th 2008 with implementing of the Anti Terrorist Act. The plan consisted of two options. Plan A revolved around getting Icelandic authorities on board with moving Icesave to the UK, which was to include proper insurance premium funds coming with it. If however, that would not work out, plan B was quite simply unilaterally seizing the bank.

As mentioned before, until Friday October 3d, Treasury officials believed a deal was in place with Icelandic authorities. Over the weekend however the UK side lost faith in the Icelanders, resulting in Plan B being kicked into action. The above mentioned investigative report prepared for Icelandic stakeholders also indicates that the UK side feared that the government of Iceland was losing control over to Central Bank governor Davíð Oddson, the country’s previous long standing PM and that he was planning to ‘veto the scheme’ – that is, the alleged deal on moving Icesave against 200 million pound insurance premium. The report also noted an expectation existing in the UK that the nationalized Icelandic banks would be ordered to reclaim their funds from abroad following such an Oddson veto. Furthermore, hints of Russian rescue money flowing to Iceland caused further concerns of Iceland going rogue.

When coming to the conclusion of applying plan B, UK officials interviewed for this paper claim that when dealing with Iceland, Brown and Darling wanted to been seen as being tough on rouge bankers. They pointed out that Iceland was viewed to be small enough to be made an example off; that it might serve as stark warning to others. Thus, when the big bank bailout was announced on Wednesday October 8th 2008, being tough on Iceland set the right political tone domestically, i.e. being tough on bad bankers while also preventing the banking system from collapse. Thus, this was also a balancing act. Applying the Anti-terrorism Act against Iceland was thus purposely used by the UK government to send a strong message and in doing so preventing others from straying off from the right path.

UK officials interviewed for this paper agree that the UK government had no idea what implication their action would have on the Icelandic banking system, that they were not thinking about Iceland as such in their actions, that this was quite simply only about British politics in time of crisis and that they did for example not contemplate Kaupthing collapsing as a result.

This view of events is somewhat supported when examining conversation between Icelandic Finance Minister Mathisen and Lord Paul Myners, the British Financial Services Secretary, on 8th October 2008. Myners said that it had worried UK authorities not being able to get reliable information out of Iceland on whether British depositors would be compensated or not. Lord Myners said that the UK government had thus decided to take action in protecting British financial interests against Iceland (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 151). When discussing the issue in the House of Lords on 28th October 2008 Myners cited the same reasons for applying the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act, that is; lack of sufficient commitment from Iceland regarding deposits in the UK but also adding that the actions had been necessary because of volatility on the UK financial market. He said it had been necessary to act vigorously when Iceland seemed to be taking actions hurting British interests (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 154).

Quite clearly, we can conclude that these actions were a co-ordinated attack that had been in the making for days, if not weeks. Indeed, it was a bomb, which was to blow up the defensive wall that the Icelandic government was trying to build around domestic households.

When PM Haarde called in the morning on Thursday 9th October to complain about this brutal treatment, Brown did not even answer. Haarde was instead referred to Darling, who in their phone conversation justified the actions of the British authorities by referring to his talk with Icelandic Finance Minister Mathiesen two days earlier. Darling said that Mathisen had not been able to provide guaranty for the Icesave deposits and that he had indicated that obligations of the FME might not be honoured. Records of their 7th October conversation however do not support Darlings recollection from their talk (See SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 152). Interestingly, when interviewed for this paper a senior UK Foreign Office official pointed out that Mathiesen had made a mistake when agreeing to talk on the phone with Darling that day, by doing so he had given Darling the excuse he needed to attack Iceland. The British official said that the phone call had made it easier for the UK to apply the legislation they had already for some time been preparing to use if the need presented itself.

From correspondence between the UK embassy in Iceland and the Treasury in the UK, now partly made available by the Freedom of Information Act 2000, the UK authorities seem to have felt quite confident of success in their dealings with Iceland. On late October 11th the UK ambassador reported to London that Treasury officials were travelling back from Iceland and that a deal on Icesave was within reach. UK officials discussed imminent ‘quick wins’ in the dispute against Iceland and contemplated ‘lifeline’ to be handed to Iceland after securing their victory (See in Jóhannesson, 2014).

The Icelandic government only made weak attempts to protesting against these actions taken by the UK. On 13th February 2009 the UK Treasury finally provided explanations in a letter signed by Clive Maxwell, claiming that the actions were not taken on grounds of terrorist operations. The letter quoted instead protocol in the law saying that the Treasury can act against those whose actions are construed as being to the detriment of the United Kingdom’s economy. The letter maintained that the British Treasury had believed it to be likely that the Icelandic government was discriminating in favour of Icelandic depositors and against UK and other foreign creditors. The letter quoted the 7th October phone call between finance ministers Mathiesen and Darling, claiming that the Icelandic authorities had failed to issue credible protection to foreign depositors. The letter also stated that the Icelandic government had provided contradictory information and said that the Icelandic actions were threating financial stability in the UK and that there was real risk of contamination (SIC 2010, Vol. 7, Ch. 20: 155). This is somewhat different to the explanation Finance Minister Darling told PM Haarde in their phone call on 9th October 2008.

Forced Agreement

Though ambiguity remained over many legal aspects of this highly complex situation, the UK and Dutch governments were pressuring Iceland to accept full responsibility for the Icesave accounts. While also pressuring Iceland to turn to the IMF, these governments were, with the help of the EU apparatus, lobbying neighbouring capitals to refuse it any loans except through an IMF programme (See in Independent Evaluation Office of the International Monetary Fund, 2014). Iceland’s government, however, was still afraid of the stigma of being the first Western state in four decades to surrender to the IMF (See for example, Mathiensen & Jósepsson, 2010)

Iceland gradually caved under the collective pressure and sought help from the fund. To Iceland’s surprise, the IMF board refused help unless, Iceland was made to understand, first clearing up the Icesave dispute with the British and the Dutch. Initially at the IMF yearly meeting in Washington already on October 11, Finance minister Mathiesen signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Dutch where he agreed to an arbitrary court ruling on the issue. Only in its wake, on 22d October, was Landsbanki removed from the list of terrorist regimes on the UK Chancellor’s website. This agreement was however abandoned by the Icelandic government upon Mathiesen’s return in Reykjavik and in November it was replaced with a much more broadly based deal, what was called the Brussels Guidelines, which included EU involvement. The deal stipulated that Iceland would indeed accept responsibility, but that its European partners would help shouldering the cost. Holding out for not much more than a month, the government thus threw in the towel and under impossible pressure, accepted to guarantee deposits up to the minimum €20,887 stipulated by EU Directive 94/19/EC.

The EEA connection did not amount to much. IMF assistance was only made available after Iceland gave into the Dutch and the British. The government’s apparent weakness in responding to the UK attack added to the public’s frustration, especially when it had become clear that no money had illegally been moved out of the UK.

The initial forced Icesave agreements (The Memorandum of Understanding and the Brussels Guidelines) angered the public, which in wake of the Crash had taken to the streets in ever-greater numbers. After a series of protests, which later became known as the Pots and Pans Revolution (búsáhaldabyltinging), the grand coalition of the Independence Party (IP) and the Social Democratic Alliance (SDA) was ousted from power in late January 2009, paving the way for a new left-wing government – the first purely left-wing coalition in the history of the republic.

The severity of the currency crisis, which followed the banking collapse, can for example be seen in the fact that Iceland was the only country that had to revert to such extreme measures as implementing capital controls. The economy seemed paralysed. On Friday 10 October, the first of many popular protests started.

While the crisis was tightening its grip leading up to The Crash, Iceland’s neighbours had refused help unless it was through an IMF programme. After the collapse of the banks, the IMF gradually emerged as Iceland’s only viable option as it was still being isolated internationally. The British and Dutch governments had been successfully lobbying both the ECB and other European states not to aid Iceland independently, while at the same time pressuring Iceland to accept responsibility for the Icesave deposits. Iceland’s government, on the contrary, insisted that according to Directive 94/19/EC it was only obligated to ensure that a Depositors Guarantee Fund was in place and not explicitly responsible for foreign branch deposits (Blöndal & Stefánsson, 2008). Referring to a report written for the French Central Bank in 2000, Iceland argued that the Directive did not explicitly dictate that the state had to pick up the balance in the event of a systemic collapse (Banque de France, 2000).

This was, however, a difficult argument to get through in the crisis-ridden climate at the time. In order to prevent a further run on their own banks and to regain enough credibility to keep them afloat, the British, during these same days, led a coalition of G20 and EU states promoting collective international action emphasizing almost blanket depositors protection (see, for example, Pilkington, 2008). Allowing Iceland to leave depositors in foreign branches without such protection was seen as countering these efforts and indeed undermining the entire global financial system. In Whitehall, many feared that the Icelandic crisis was spreading to the UK, which also had approached the brink of widespread banking collapse. As a result, Iceland was being turned into an international villain. Iceland was trapped.

Though Iceland was still stubbornly hesitating, a joint economic programme was informally being negotiated that would include $2.1 billion from the IMF and a further $3 billion from the Central Banks of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden in addition to a separate loan from Poland. Iceland’s resilience was however diminishing by the day. The pressure to accept responsibility for the Icesave deposits grew. According to some reports, Iceland was even threatened with being expelled from the European Economic Area (EEA), its economic lifeline to the outside world (Hálfdanardóttir, 2008). With dwindling foreign reserves and at risk of a serious shortage of, for example, medicine, food and other necessities from abroad, Iceland finally threw in the towel and applied to enter the IMF emergency program on 25 October.

IMF Blockade

Based on informal query the government expected that the IMF board would accept Iceland’s application on 3 November (Sveinsson, 2013). In the meantime, however, the British and Dutch governments, which previously had been pressuring Iceland to go to the IMF, were now lobbying behind the scenes against Iceland being allowed into the program unless first accepting responsibility for the Icesave accounts (Duncan, 2008). The NRC Handelsblad in the Netherlands reported that the blockage was being orchestrated by Dutch Finance Minister Wouter Bos and his British colleague Alistair Darling (Banning & Gerritsen, 2008). Later, the chief IMF representative in Iceland admitted to a block of not only the British and Dutch governments but also the Nordic states (Rozwadowski, 2013).

When Iceland would not concede, the IMF board postponed its decision and made clear that the plea would be blocked until accepting of liability for Icesave. During this time, a senior advisor in the IMF’s external relations department publicly acknowledged that the delay was directly due to unresolved disputes with the Netherlands and the UK (Transcript of Press Briefing by David Hawley, 2008). As Iceland was not a member of the EU and thus not subject to the European Court of Justice, and as the EFTA Court had no jurisdiction in the UK and the Netherlands, there seemed at the time to be no available legal body to rule on the dispute – apart from the previously mentioned initial arbitrary court that Finance Minister Mathiesen had felt forced to agree to on October 11 but the Icelandic government later abandoned on the ground that it was skewed in favour of the UK and the Netherlands through the EU’s involvement.

Iceland was thus caught in a tight spot. It needed money to prevent further deterioration of the already devastated economy but that meant agreeing to liabilities it did not want to accept. According to the Brussels Guidelines brokered by the French EU Presidency the government of Iceland agreed to cover the deposits of depositors in the Icesave accounts in accordance with EEA law. Iceland was to repay the Icesave debt over ten years, starting three years after signing, with 6.7 per cent interest on the loan. The agreement also entailed that the EU would continue to participate in finding arrangements that would allow Iceland to restore its financial system and economy. This was a precondition Iceland set for paying out according to the agreement. A stabilization package of financial assistance from the IMF was an explicit part of the agreement, which was to be discussed at the IMF Executive Board meeting on Wednesday 19 November (Agreed Guidelines, 2008).

Though these early agreements on the Icesave deposits were meant to end the quarrel, the dispute was only just starting. Ambiguity still remained. To keep up the pressure, and even to increase it, the Dutch Foreign Minister, Maxime Werhagen, threatened to veto Iceland’s EU bid in July 2009 (The Hague Threatens Iceland, 2009). The Icelandic government justified the agreements by claiming that it had had no choice. Either it bit the bullet and accepted responsibility or the country would remain frozen out, thus without access to vital imports such as medicine and food. The Icelandic government explained that no one supported us; not even our Nordic neighbours were willing to listen to Iceland’s legal arguments. Without agreement, Iceland would no longer have been considered a modern state, internationally recognized as equal to others, but would rather have been relegated to being an isolated outpost surviving on local agriculture and fisheries alone. The signing was, however, a serious blow to the country’s political identity, as the postcolonial national identity insisted on not giving in to foreign pressure. It thus caused great strain domestically (Bergmann, 2014b).

After Iceland’s concession to the British and the Dutch over Icesave, the general public took to the streets in even greater numbers than before, now not only protesting against our government’s mismanagement of the economy but also against apparent foreign oppression. Frustration grew as businesses closed and more and more people were laid off while inflation rose to 20 per cent. The protest was now spreading around the country.

Icesave II and III

The new left-wing government parachuted in on the canopy of the Pots-and-Pans revolution contested some of the premises of the Brussels Guidelines, which they claimed was unlawfully imposed by foreign forces. Under the leadership of Finance Minister Sigfússon, chairman of the Left Green Movement, the new government abandoned the multinational approach and instead sent their representatives to London and The Hague to renegotiate terms. This result, which in effect was merely a loan agreement with the foreign ministers of the Netherlands and the UK, where Iceland accepted to cover up to €4.5 billion, instantly became one of the most unpopular agreements in the history of the country. Only after it’s signing however was the freezing order on Landsbanki and related Icelandic assets lifted.

Similar delaying tactics within the IMF on reviews, as when entering the program initially, was furthermore confirmed in a report by the Independent Evaluation Office of the IMF into its response to the financial crisis. The report spoke of ‘the active involvement of (at least some) Nordic countries served to delay the first review by several months because […] pressure […] by their European partners not to provide financing assurances in an attempt to influence the outcome of the ongoing discussion on the extent of deposit guarantees for Icesave.’ (Independent Evaluation Office of the International Monetary Fund, 2014)

Parliament reluctantly accepted the agreement, but only after adding to it new preconditions, referring to Iceland’s ability to pay. These the UK and the Dutch refused. A new negotiation committee was thus formed, which was able to lower the interest rate a little further. After a fierce debate, the amended agreement was accepted in Parliament on the last day of December 2009. The new government was now also accused of caving in to foreign pressure and surrendering Icelandic interests to external forces.

The saga took a dramatic turn on 5 January 2010, when the President of Iceland, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, denied signing the law necessary to ratify the new agreement after receiving a petition of 60,000 Icelanders asking him to reject the deal. (He had signed the revoked earlier one). This was an exceptional move.

In early 2010, Icelanders once again found themselves in unknown waters. A quarter of the electorate had signed a petition to be put to the President asking him to decline signing the bill, which was thus as a result of the non-signing subsequently put referendum were 90 per cent of voters refused ratifying it. The country was in a mood of defiance. Many felt betrayed by the UK government when it had invoked the Anti-terrorist Act – an action that ultimately drove our last bank into the ground. Icelanders therefore found the idea that they should foot the whole bill alone difficult to swallow. There was also a legal twist. Directive 94/19/EC upon which the British and Dutch had based their claim was rather unclear. It stipulated only that states are obliged to set up special deposit guarantee schemes. It did not speak of a state guarantee. Many Icelanders were thus frustrated by the fact that the British and the Dutch had refused the request for an impartial court to rule on the issue.

The general perception in Iceland was thus that the government had again been bullied by an overwhelming foreign power into signing an unjust agreement. It is generally accepted that the government and Parliament only accepted the initial deals to achieve other ends, rather than because they felt under obligation to pay. It was simply a necessary evil to gain access to the IMF. And then there was the cost. €4.5 billon might have seemed a small figure by UK standards but this was almost half Iceland’s GDP. Divided by Iceland’s small population, the bill amounted to more than €12,000 per head, or just under €50,000 per household. If Landsbanki’s assets deteriorated any further, this would place a devastating burden on an already debt-ridden population.

In addition to the wide-ranging general feeling of frustration, the appearance of leniency towards the British and Dutch spurred a new wave of protest in mid-2010, which heightened when Parliament resumed in the early autumn, to find thousands of protesters surrounding the building, once again.

After twice going back on signed agreements (in addition to abandoning the two initial deals), the government found it difficult to go knocking on doors in London and The Hague asking to renegotiate the deal once again. Headed by a hired American negotiator, the new team was nevertheless in the end able to bring the interest rate down to 3 per cent. This time, a large majority emerged in Parliament when the IP joined ranks with the government in backing the new deal. The Progressive Party (PP) though still opposed any agreement. Yet, to the surprise of most, President Grímsson also refused the third agreement. In a second referendum, on 9 April 2011, the new agreement was refused by a two-thirds majority, illustrating a clear division between Parliament and the public. Now, there was no longer anything to negotiate. The case was sent to the EFTA Court, where the EU was backing the claim of the UK and the Netherlands and the EFTA Surveillance Authority against Iceland. Finally, on 28 January 2013, the court ruled in favour of Iceland, which was vindicated of wrongdoing in its handling of the Icesave deposits (Judgment of the Court, 2013). The court refused the EU’s and the UK and the Dutch governments’ claims of a state guarantee, such as Iceland had been forced to accept in the earlier Icesave agreements. Later UK and the Netherlands filed a much more limited claim before court in Reykjavik, still pending judgment at time of writing.

Conclusion

Internationally the Icesave dispute reveals interesting contestation and political production (and re-production) of constitution of international legality. Development of international legality, as understood by Rajcovic et al (2016), has in this paper been traced throughout the course of this particular crisis. Domestically the issue was dictating politics in the post-crisis period in Iceland. To the surprise of many Icelanders, after the Crash had left Iceland in financial ruin, the Dutch and the British still enjoyed the full backing in the Icesave debacle of our neighbours in the European community. The UK and Dutch authorities were able to use both the EU and the IMF to pressure Iceland into accepting responsibilities that Iceland’s authorities never believed were theirs to shoulder.

From interviews with UK officials conducted for this paper is seems clear that the UK side believed that a high level political deal was in place with the Icelandic government of fast tracking Icesave into the UK banking space and that the deal included insurance premium injection from Iceland of 200 million pounds. Interestingly, though, Icelandic officials claim not to have any knowledge of such a deal. It is furthermore evident that the UK government lost faith in Icelandic authorities during the weekend of 3d to 5th October 2008, finally kicking into action plan B of attacking Iceland by use of the Anti-terrorist Act, which had for a while been in the making in Westminster. When doing so it served the UK government well to take a tough stand on Iceland, while simultaneously bailing out banks domestically – being tough on Iceland became a balancing act, serving the purpose of sending tough message to others when announcing the massive bank bailout.

The Icesave case illustrates that in time of crisis international muscle power still prevails. In time of need small states have difficulties when defending off larger states sharp attacks. In a European context, being formally a non-EU member made it easier for the UK and the Netherlands to deploy the EU apparatus to pressure Iceland than they would against a fellow member state. The illusion of a shelter amongst the family of Nordic states was furthermore also shattered during Iceland’s Crash, which was therefore not only economic but also political and indeed psychological. Iceland had been frozen out in terms of diplomatic relations. Suffering the deepest crisis in its post-war history, the country was already drained of foreign currency when the IMF finally opened its doors in November 2008, after Iceland had, under coercion, finally agreed to guarantee the Icesave deposits. By use of delaying tactics of reviews within the IMF the UK was, with the help of some of the Nordics, able to maintain the pressure on Iceland. However, after the immediate crisis was over, it was through the EFTA Court, a European institution, that Iceland, as a small state, was finally able to escape the pressure applied by the British and Dutch governments.

References

Independent Evaluation Office of the International Monetary Fund. (2014). IMF Response to the Financial and Economic Crisis: An IEO Assessment. Retrieved from http://www.ieo-imf.org/ieo/pages/EvaluationImages227.aspx#

Árnason, S. (2007, 02). Lætur aldrei efast um fjármögnun bankans. Fréttablaðið. Reykjavik.

Balakrishnan, A. (2008, 10). UK to sue Iceland over any lost bank savings. The Guardian. London. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/oct/08/iceland.banking

Banning, C., & Gerritsen, J. (2008, 11). Dutch and British block IMF loan to Iceland. NRC Handelsblad.

Benediktsdottir, S., Danielsson, J., & Zoega, G. (2011). Lessons from a Collapse of a Financial System. Economic Policy, 26(66), 183–235.

Bergmann, E. (2014). Iceland and the International Financial Crisis: Boom, Bust & Recovery. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Blöndal, L., & Stefánsson, S. M. (2008, 10). Ábyrgð ríkisins á innlánum. Morgunblaðið. Reykjavik.

Brown Blasts Iceland Over Banks. (2008, 10). Sky News. Retrieved from http://news.sky.com/story/640086/brown-blasts-iceland-over-banks

Brown condems Iceland over banks. (2008, 10).

Buiter, W. (2008, June 2). There is no excuse for Britain not to join euro. Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/fa2a465a-30bc-11dd-bc93-000077b07658.html#axzz2UrjoJeFr

Darling, A. (2008, 10). Extra help for Icesave customers. BBC Online. London. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7658417.stm

Duncan, G. (2008, 10). IMF bailout of Iceland is delayed until fate of UK savers’ frozen cash is resolved. The Times. London. Retrieved from http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/business/economics/article2148643.ece

Haarde, G. (2008, 10). Ávarp forsætisráðherra vegna sérstakra aðstæðna á fjármálamarkaði. Ávarp forsætisráðherra. Reykjavik: Sjónvarpið.

Hálfdanardóttir, G. (2008, 11). ESB hefði jafnvel sagt upp EES-samningnum við Ísland. Mbl.is. Reykjavik.

Halldórsson, Ó. G., & Zoega, G. (2010). Iceland’s financial crisis in an international perspective. Retrieved from http://rafhladan.is/handle/10802/1898

Hreinsson, P., Gunnarsson, T., & Benediktsdóttir, S. (2010). Report of the Special Investigation Commission 2008. Rannsóknarnefnd Alþingis. Retrieved from http://www.rna.is/eldri-nefndir/addragandi-og-orsakir-falls-islensku-bankanna-2008/skyrsla-nefndarinnar/english/

Hussain, A. (2006, 10). Icesave looks like a hot deal. The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved from http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/business/money/savings/article158555.ece

Ibson, D. (2008, 08). Icelandic banks’ results calm fears. The Financial Times. London. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f908fae6-6172-11dd-af94-000077b07658.html#axzz2NtoDOIX0

Is Iceland headed for meltdown? (2008, May 2). The Daily Telegraph. London.

Jóhannesson, G. T. (2014). Vitnisburður, aðgangur og mat heimilda. Bresk skjöl og bandarísk um bankahrunið á Íslandi 2008. Saga.

Jónsson, Á. (2009). Why Iceland?:[how one of the world’s smallest countries became the meltdown’s biggest casualty]. McGraw-Hill.

Júlíusson, Þ. S. (2009, 02). Eftirlitin skoðuðu flutninga á fjármagni til Kaupþings. Morgunblaðið. Retrieved from http://www.mbl.is/vidskipti/frettir/2009/02/28/eftirlitin_skodudu_flutninga_a_fjarmagni_til_kaupth/

Lyall, S. (2008, 11). Iceland, Mired in Debt, Blames Britain for Woes. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/02/world/europe/02iceland.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Mathiensen, Á., & Jósepsson, Þ. (2010). Frá bankahruni til byltingar. Reykjavik: Veröld.

Murphy, P. (2008, 10). Who will stand up for Iceland? We will. The Financial Times. London. Retrieved from http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2008/10/10/16900/who-will-stand-up-for-iceland-we-will/?Authorised=false

Pilkington, E. (2008, 11). Gordon Brown heralds progress at G20 financial crisis talks. The Guardian. London. Retrieved from http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2008/nov/15/economics-globaleconomy1

Rajkovic, N., Aalberts, T., Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. (2016). The power of legality: Practices of international law and their politics. Department of European and International Public Law. Cambridge University Press.

Rozwadowski, F. (2013, 01). Jákvæð áhrif á lánshæfismatið. Fréttablaðið. Reykjavik.

Samtal Árna og Darlings. (2008, 10). Morgunblaðið. Reykjavik. Retrieved from http://www.mbl.is/frettir/innlent/2008/10/23/samtal_arna_og_darlings/

Sveinsson, S. G. (2013). Búsáhaldabyltingin. Reykjavik: Almenna bókafélagið.

The Landsbanki Freezing Order 2008, Pub. L. No. 2008 No. 2668 (2008). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/2668/contents/made

Thorvaldsson, A. (2009). Frozen Assets: How I Lived Iceland’s Boom and Bust. London: Wiley.

Wade, R. H., & Sigurgeirsdottir, S. (2010). Lessons from Iceland. New Left Review, 65, 5–29.