This is not a scholarly article. It is rather a set of my observations and opinions sparked by the massive scorning, cursing and trolling of the year 2020, which can now be encountered abundantly all over the internet, other media, and in private conversations. This article does draw upon general knowledge of ethics, philosophy, sociology, psychology and history but, nevertheless, it remains within the scope of my personal and highly limited worldview. The idea of the article is to show why such treatment of a calendar year is highly erroneous and immoral, and how it mirrors a general imbalance in human scale of values.

The Setup or The Importance of Every Stone

Firstly, what is a calendar year? I have never asked myself that question until now, simply because the answer seemed trivial to the point where the question itself loses any purpose. The year is comprised of the 365 days between the midnights of January 1 and December 31. The two dates are marked as the moment that human beings typically prefer to celebrate with fireworks, travelling, partying and excessive eating and drinking. More specifically, a year is a mental construct, which is confirmed, measured and distributed by mechanical devices we have developed in order to control the temporal aspect of our experience of being. A second is an idea, so is a year – finally, that makes our division of time a construct forced upon nature. Surely, the temporal placement of the end of the year does follow the pattern of the four seasons – it is comfortably imagined as the first act of winter, the time when people of the past had to slow down, take a rest, and, following nature’s pattern, prepare for a new start. However, do not forget that this correspondence between the end of the year and nature is valid only for the moderate climate belt, more precisely, for most of Europe, and it only reveals the Eurocentric nature of our past rather than any solid connection that the 365 days long period could have with global climatic reality on Earth. Finally, different cultures used, and still use, different calendars to mark the end of the year at different times.

The other important fact which anchors the year into the natural order comes from further observations of the Earth’s surface – it comes from the movement of our planet through the dimension we named the Universe. In these 365 days, as many ancient astrologists noted centuries ago, our planet makes a full circle around the Sun. It is realistic to understand this as an ultimate proof that the one-year period as a mental construction is indeed intrinsically rooted in natural laws, however, in my opinion, there is yet another issue we have to consider. That issue is human binary thinking; a shared mind setup which forces us to divide everything into units that, according to us, can be subdivided into smaller building blocks which always include one beginning, a duration, and one ending. In that sense, humans maybe could have agreed a long time ago that ‘a year’ is half of the Earth’s trip around the Sun, or perhaps two rounds. In the first case, the year today would be 4042, in the latter 1011. Although this would follow some rules of binary logic, it would break the principal one: ‘completion’. One year must be one full turn with a distinctive beginning and ending. It is interesting, just as a short aside, that humans, although they are intrinsically a binary-thinking species, fervently reject the idea of two basic endings in their logical constellation, the ending of their lives, and the ending if the Universe. To bypass their anxiety about dying, they constructed beliefs that later developed into spiritualties and religions, and the theories for avoiding the discomfort caused by the lack of knowledge about the Universe developed into scientific postulates of the Universe being ‘infinite’.

If the entire Universe is based on strict binary logic, which I find hard to believe, then it surely has an ending (maybe it is exactly the shift from binary into a different logical system that marks this ending), or better said, a spatial border where it turns into a slightly or significantly different system. Of course, you can persist in calling that other system ‘the Universe’ as well, but keep in mind that Columbus called the Caribbean Islands ‘India’. What is a non-binary thinking? I do not want to go into this, as it would take too much time and detach me from my main theme, but one thing is for sure: in a non-binary logical system, time would be something entirely different. We almost surely would not need ‘a year’, or any other such measurement at all. To conclude, my opinion is that the idea, based on binary logic, that one voyage of the Earth around the Sun forms a one ‘year’ period, although based on a natural cycle, is still is largely a human mental construct imposed on nature.

Now, imagine there was a specific ‘year’ long period that was perceived by humans as so misfortunate that it became evil itself, a time so globally detested, even by those with serious educational backgrounds, that it became the year that ‘everyone wants to forget’, a symbol of ‘cruel and unjust nature’ taking it out on our poor species. This is, of course, ‘the cursed’ year 2020, the year that destroyed our small human dreams with viruses, bad weather, earthquakes, difficult economic conditions and depression. The Internet and the media these days are burning with mournful and vindictive messages, such as: ‘2020-Go Away!’ or ‘2021, save us from the beast!’ The year 2020 itself was transformed into a global effigy, and everyone around the world is invited to cast a stone at it. In my opinion, this belies a deep problem in the human perception of reality, an intrinsic systematic error, much more dangerous than, for example, flat Earth theories, which are based almost solely on ignorance. The year 2020 is being publicly burned as an effigy at a global carnival celebrating the most frightening limits of human perception. This human behaviour also shows that we, as a species with a set of cultural practices, have not made significant progress from tribal origins based on fear and ideas of safety rooted in collectivism. This also inevitably makes us a naïve species, and, although an easily lovable one, rather sad, and fated in the sense of Greek tragedy. But much more importantly, this attitude towards a calendar year shows our darkest side: an utter lack of morality and any sense of responsibility, issues I will touch upon individually in the next passages. For now, as a quick and perhaps displaced observation, I will just note that our civilization viewed from the Universe might look like a dangerous skin disease on the planet’s surface.

Human beings have managed to shoot a few members of their species out into the surrounding Universe and safely return some of them to Earth. There are two comments that I would like to offer here, even at the risk of the first comment sounding arrogant and ignorant. Launching anything from the surface of anything, and getting it back down, is a matter of sheer physics. It takes a large number of competent scientists to calculate the physics of every part of the voyage, including all variables and possible scenarios. This is, indeed, a complex and time-consuming process that takes a lot of knowledge, dedication, courage, preparation and even creativity. Trips into the Universe are arguably the peak of our technological development. However, these trips are based solely on mathematical calculations – almost endless sequences of numbers, exact results and approximations as well. Numbers. It is my personal opinion that calculating an orbit and then constructing the device that can execute that orbit is certainly an amazing accomplishment but philosophically as trivial as scoring a point during a basketball game. Not to mention the fact that for such space endeavours we use fossil fuels and create tons of terrestrial and atmospheric waste. Human beings continue to destroy the planet in the course of the production of these fuels and the technical components required for space travel (all of which cost billions, while every second on Earth an infant life is taken by starvation). That such advanced knowledge and the rockets that are its expression are seriously employed for the planned evacuation of their species once they have entirely ruined the Earth only shows that homo sapiens has fallen into an abyss of immorality and lunacy.

Here comes my next comment on our amazing technological development: Every square millimeter of untouched nature on Earth is more important than anything humans have ever achieved. Every stone matters, and, if the stone has to be moved or destroyed, it has to be done in accordance with the laws of nature that preserve global balance, the balance we and everything around us depend on. In other words, although a human being or an animal can move or even break the stone, although the water, sunlight and temperature will inevitably damage the stone over time, that stone has its own rights. Let us call them the legal rights of every stone. This law is natural law. The first central tenet of the law is, what I call, the ‘temporality of balance’. We all know by now that everything around us changes, for example, mountains descend due to erosion, new islands are born from lava, lakes get sucked into ground after earthquakes, the sea level constantly changes, continental masses are slowly moving, the climate is in constant shift, entire rain forests turn to desert, various species disappear and new ones emerge. All these changes happen at a pace strictly determined by the logical laws of nature. This pace is typically slow, in the sense that it gives time for species to adjust (‘slow’ in that sense, because in every other sense ‘slow’ is too ethereal to define). Of course, there is plenty of evidence that some global changes in nature were abrupt and that they have caused mass extinction of numerous species. However, even these abrupt changes were always the result of natural causes and exercised upon and with natural materials, in other words, nature only rapidly rearranged itself. There was no, for example, plastic involved, let alone depleted uranium. In that sense, abrupt global changes in nature, although very rare, were themselves natural in essence and in their result. However, the majority of changes on Earth, and in the known Universe, are perfectly adjusted to the need of ‘slow and gradual’ evolution and survival. That pace of temporality of balance was never constant. We now know that most changes in nature at some point accelerate exponentially. That is usually the case in the later or final phases of every change. Even that final acceleration of pace does not put ecosystems in jeopardy; on the contrary, it opens space for natural new beginnings.

It is interesting to note that all living beings, not just humans, to an extent interfere with the temporality of balance. It seems that the simpler life forms are employed to control the stability of the pace of changes, and that is their contribution to this balance. More complex life forms can sometimes display a behaviour that can be described as egoist and borderline destructive. For example, an elephant is able to destroy and kill a tree just to get a decent scratch on its back. On a funnier note, they say the most potent natural source of carbon-dioxide on the surface of the earth is in the intestines of cows, and that, if all the cows in the world would simultaneously empty their carbon-dioxide stashes, the atmosphere would be in serious trouble. The fact is that cows will never do that. And a herd of elephants destroying trees for pleasure will never lead to the extinction of forests.

Let us imagine that both elephants and cows display a human-like intelligence. Elephants would mark their own parts of forests and motivate other elephants (who are excluded from forest ownership) to scratch their backs on their trees. For that service, they would ask for money. In the advanced phase of greed, elephants would motivate their friends to not only scratch when they really need a scratch but every time they want to amuse themselves. That would lead to the destruction of forests, and elephants would have to find new forests for exploitation. Eventually, that would lead to the extinction of all forests, and elephants would be left in scorching sun, some of them penniless, some of them rich, but none of them able to get a decent scratch, nor food, for that matter.

Considering cows as well displayed aspects of human intelligence, it would be enough for one of them to announce that releasing carbon dioxide anally is a spectacle that elephants would gladly pay to hear – and all of the cows would start greedily releasing gases. Some of them would start overeating to produce more gas and thereby generate more profit. Then, some of the cows would start producing plastic balloons for ‘take away gas’. Elephants would buy these balloons, laugh at the sound of the gas released from them, and eventually throw the used plastic balloons on the ground. The resulting overexploited and barren pastures could not renew themselves due to the high level of carbon dioxide in the air. Both cows and elephants would become extinct. The only thing left would be reeking winds carrying non-degradable plastic waste. We have to understand that either elephants or cows would eventually become extinct or evolve into a new species over time. The time determined by the temporality of balance, and typically spanning millions of years. But with human intelligence, cows and elephants would, I suppose, become extinct much more quickly.

This illustrates our biggest crime against nature – we as a species have irreversibly accelerated the pace of the temporality balance. This is now a different type of balance – one that will not spare us any possible consequences. How did we speed up the pace of change? Quite simply, by moving the stone. Crushing it to powder. Painting it with chemical color. By exploding it, or sealing it into concrete. By radiating it. By not realizing that the millennia-old lines carved in the stone were just as much a work of art as any of, for example, Dali’s paintings. By thinking that there is any deity above that stone. The disrespect for one stone led to the destruction of the entire planet.

We often hear that the theories of global climate change are a hoax. That the changes were happening anyway, and that humans had very little or nothing to do with accelerating them. That the planet has let us down, and we will simply atom bomb Mars to create atmosphere and move there. In my opinion, even without climate change, but with the current intensity of human activity, the planet would soon become too toxic to live on anyway. But climate change is here as a logical consequence of our toxic behaviour, and it will shorten our time to develop immunity to our own toxins, making our extinction (or, at least, that of most of us) quite evident. Unfortunately, with us and because of us, even the innocent species like elephants and cows will disappear. Furthermore, those who talk about human innocence in breaking the first tenet of natural law are typically either the rich and powerful or the ignorant. Both need to believe in human innocence simply because the first group offers scratching, and the second group needs it. All this for a handful of dollars.

Let us now return to human space expeditions. Imagine if Nature personified were to appear at the launch site of a space rocket and order humans to make the launch three times faster. All the scientific calculations would be in vain because the balance of human calculations would be disrupted. Humans would be left only with an unrealistic hope that the space voyage would take the same course even with altered physics. This is what we have done to nature’s temporal balance.

My final remark on the temporality of balance is the sad fact that human beings cannot restore its natural pace by further interventions, even ‘positive’ ones. In this unforgiving circle of logic, every human action, even those with good intentions, cause further changes, which trigger new chain reactions. It is a bit like the plot of the Back to Future movies. Whatever we do with unnatural materials, especially on a large scale, seems to bring just as much damage as benefit. And for good reason: We do everything in an unnatural way and with unnatural materials because we are a species entirely detached from nature. In that respect, it would be perhaps the best for humans to entirely suspend activities and ‘development’ for a century or more. Just remember how much nature has gained in a few months of human quarantine due to the Covid-19 virus. Of course, the notion of people giving up their plastic dreams is almost a utopia in itself. Extinction appears to be the correct ending.

The second basic tenet of natural law is the justifiability of actions. By actions, I mean all the activities that alter our environment. That covers everything from starting a fire, plucking a flower, hunting and fishing, to demolishing mountains for stone quarries and murdering rivers with dams. It is clear that almost all the actions by animals in nature are entirely justifiable. And those rare actions by animals that cannot be justified are never massive, serial, organized, globally or statistically significant. On the other hand, humans have to learn that nature is not something God-given to them to exploit, alter and ruin. That one stone – that is the god, and parts of untouched nature are our last true shrines. We are here to benefit from the land and protect it, rather than to overexploit and subdue it.

I have noticed a repulsive process in my homeland that is related to tourism – ecologically one of the most detrimental branches of the economy, which I will illustrate in a hypothetical example. Imagine a small fishing village in relative isolation, connected to other, larger settlements by a narrow road. The village consists of ten old stone houses. Villagers fish mostly for their own needs, they create very little waste, they are relatively poor but have everything needed for survival. They are also relatively healthy, and a few villagers are older than 100 years of age. Around the village are barren stony hills carved by the natural elements for millennia. On the slopes of these karst hills are small herds of sheep. Where the hill slopes meet the sea, the power of water has carved sandy beaches of indescribable beauty.

At one point, the villagers realize that people in other settlements earn more and more from tourism. They try to lure tourists to their village but in the beginning it is hard. Only the adventurous tourists visit, and they leave with stories of untouched nature and hidden virgin beaches that only a few outsiders have had the chance to enjoy. The word spreads, and more tourists wish to visit the village. Investors recognize the chance for easy money. They offer villagers impressive amounts of cash (at least to the villagers) for barren plots of land close to the sea, which were for centuries considered basically worthless. Some villagers become incredibly rich. They immediately rebuild their old houses and add apartments and rooms for tourists (these additional rooms, floors and objects typically lacking any aesthetic value). The investors level the beaches and surrounding terrain and cover it with concrete. This is to make the tourists’ approach to the sea easier. They devastate large portions of natural land to create endless parking spaces. They carve into the slopes of the hill to build hotels and restaurants, with sewers (as was the practice through the most of the twentieth century) running directly onto the beaches. Now new private concrete apartments are built, each with its own concrete approach to the sea. The village suddenly consists of forty edifices, most of them weekend and summer houses, and hotels. The road to the village is widened. The village is now packed with people during the summer. They produce an enormous quantity of garbage that the investors do not care about, and the villagers do not know (or do not want to know) how to dispose of. The approach to the virgin beach is paved. The plot of land between the road and the beach is privately owned, and the owner now decides to level the natural wild wooded area, to create a large concrete-covered parking lot that will make him millions. He also adds kiosks selling drinks and souvenirs. The beach becomes a large swimming pool for an army of tourists. Fast forward a decade or two, the village now is a small town that stretches all the way to the virgin beach. All natural soil is carved up for the foundations of new houses, all natural surfaces are levelled and either covered in concrete or turned into small gardens that remind humans of their triumph over nature. The sea along the littoral belt is devastated – there is basically no life in the sea except for black and brown algae. The beaches and adjacent surfaces are covered with waste, especially plastic, and soaked with gasoline and other chemicals. The landscape that was being created for millennia is devastated under the pretence of justifiable development and the legitimate human need for profit. Although promised a better and longer life, the villagers are living under stress, with only a few of them reaching the age of 80. It is the year of the pandemics and the tourist facilities are empty. Investors and villagers are on the verge of bankruptcy. They are anxiously sitting in their poisoned town, cursing the year 2020.

Needless to say, this attitude towards nature is not justifiable. This is terror. If the villagers kept their stones and cliffs and beaches in the original, natural state, they could have made the same profit on each and every one of them. This is so because the tourists, although perhaps less numerous, would pay more to see untouched nature, and they too would treat it with more respect (and of course, the villagers also would have had the option of not entirely giving up their traditional way of life in the first place). Instead, the villagers have sold their land out, they have devastated it and, instead of acting as hosts, they acted rather as pimps. Human beings have to finally understand that levelling a piece of ancient wooded land in order to make a parking space is not justifiable. That covering the cliffs on the beach with concrete to make easier approaches the sea is not justifiable. That implanting concrete pillars into the cliffs so that the tourists could anchor their yachts a few meters from sandy beaches is not justifiable. Or that turning small wooded areas into posh mini-gardens is not justifiable. The stone is the most important, it should not be altered but we should rather adjust to it. Now imagine another thing. Human beings enter the museum to admire Michelangelo’s David. But, alas, there are problems. Firstly, David is naked, and that disturbs some of the humans. So they cut off the monument’s genitalia. Furthermore, the sculpture is too large to fit in a mobile phone photograph. So they cut it into two pieces to allow accessibility. Now the problem is David’s left arm is raised, and he is looking downwards toward his left side – so if you want to get a clear shot of his face, the hand is basically on the way. So they cut his left hand into pieces. White marble is so passé, so they paint it some more vivid colour, for example, an oily yellow. Next to the severed torso of David, they open a wooden kiosk where they sell pieces and chunks of David’s left hand to tourists.

And this is exactly what we are doing to the nature on which we depend. If you would so much as spit on the statue of David, you would finish in jail. Hence, it should not be difficult to accept that killing a natural stone is not justifiable.

The third basic tenet of natural law is that all materials should be natural and chemically unchanged. When our ancestors burned stones and extracted metals from them, this was already a significant intervention into the natural order. However, this cannot be compared with the damage created by chemically altered substances such as plastic or radioactive materials. There are two basic problems with chemically altered materials: They do not decompose quickly enough, and they typically disintegrate into smaller particles which have the same chemical features as the bigger chunks of material they originated from, hence nanoplastic pollution and radioactive winds.

Naturally, nothing could have prevented humans from creating such things as plastic and radioactive materials. Our civilisation largely depends on them. But what we could have done, as highly intelligent creatures that have walked on the Moon, was to use these materials more cleverly, and to store and recycle these materials in the most effective manner possible. It all comes down to this: We should have made sure that the contact between the natural materials and the plastic and radioactive materials was kept to the minimum possible level.

And what have we done? Let us return to the devastated ex-fishing village. Nanoplastic is in the soil and in the water. From there it enters the air. This plastic comes from the tons of plastic bags that we exorbitantly give out in shops, it comes from the over-packaging of our goods, it comes from a plethora of mostly useless and trivial plastic products that we so full heartedly purchase and that quickly finish in our waste, and now these microscopic poison bugs are everywhere. Furthermore, the villagers, when they were busy levelling wooded areas, filled the holes in the ground with debris left after construction work. This landfill is full of plastics, and now it is releasing poison under the layers of decaying concrete. Finally, (and please do understand that this is only an innocent example) there was a NATO bombardment taking place a few countries away, and the military airplanes extensively used the air corridor stretching just over the village. At some point, the airplanes had to get rid of unexploded projectiles, so they ditched them into the sea (and, mind you, this is totally legal according to the international law) just a few miles away from the virgin beach. The sea splashing the shores of the village is now two times more radioactive then a few years ago. As the shells of the projectiles continue to decompose, the radioactivity in the region will rise accordingly.

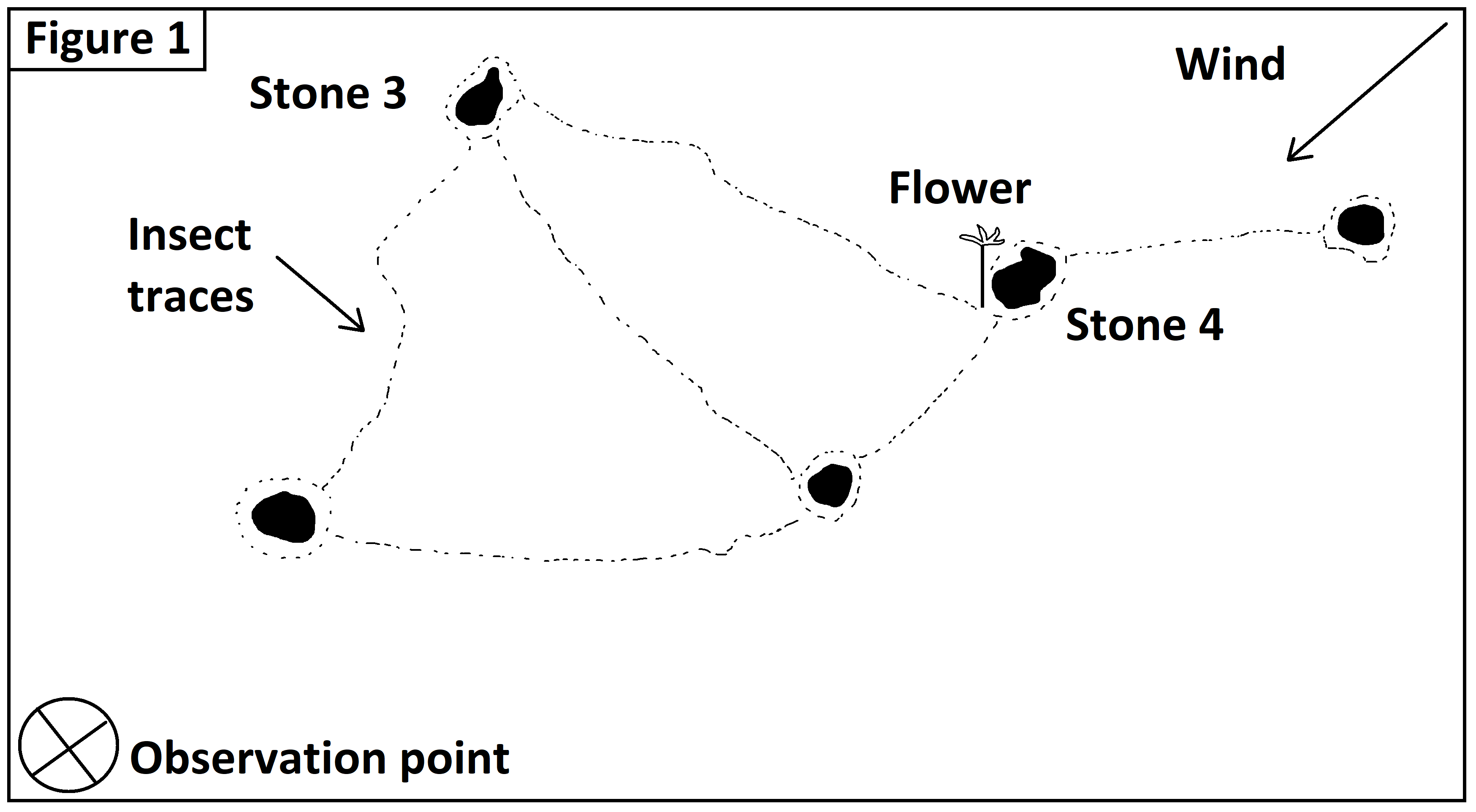

To wrap up this section (hopefully not in plastic), I will use a visual example to describe the importance of every stone and the effect of even the tiniest interventions into our environment. Imagine one-meter square of a barren, desert land (Figure 1). The land is seemingly lifeless and arranged entirely by the seemingly random rules of natural physics. The wind is blowing from the upper right corner toward the lower left corner. There are only five bigger rocks on the land, and one struggling desert flower sheltered behind the rock number four. The flower gives bloom every year in March. The land has been unchanged for at least the last 200 years. Every March, a group of scientists come to the observation point in the lower left corner.

What the scientist observe is the following:

- Stones have moved another 0.8 millimeters toward the lower left corner, as compared to the previous year.

- It was a statistically more arid year, so the flower bloomed a week later than the previous year, nevertheless, the sweet scent of its flowers could easily be felt in the wind.

- The winds were of usually observed intensity and direction.

- Traces of bugs were noticed in the sand; they seem to be distributed in circular paths around the stones, which is telling of the insects’ behaviour.

- At this pace of change, this land will remain practically unchanged for at least one more century.

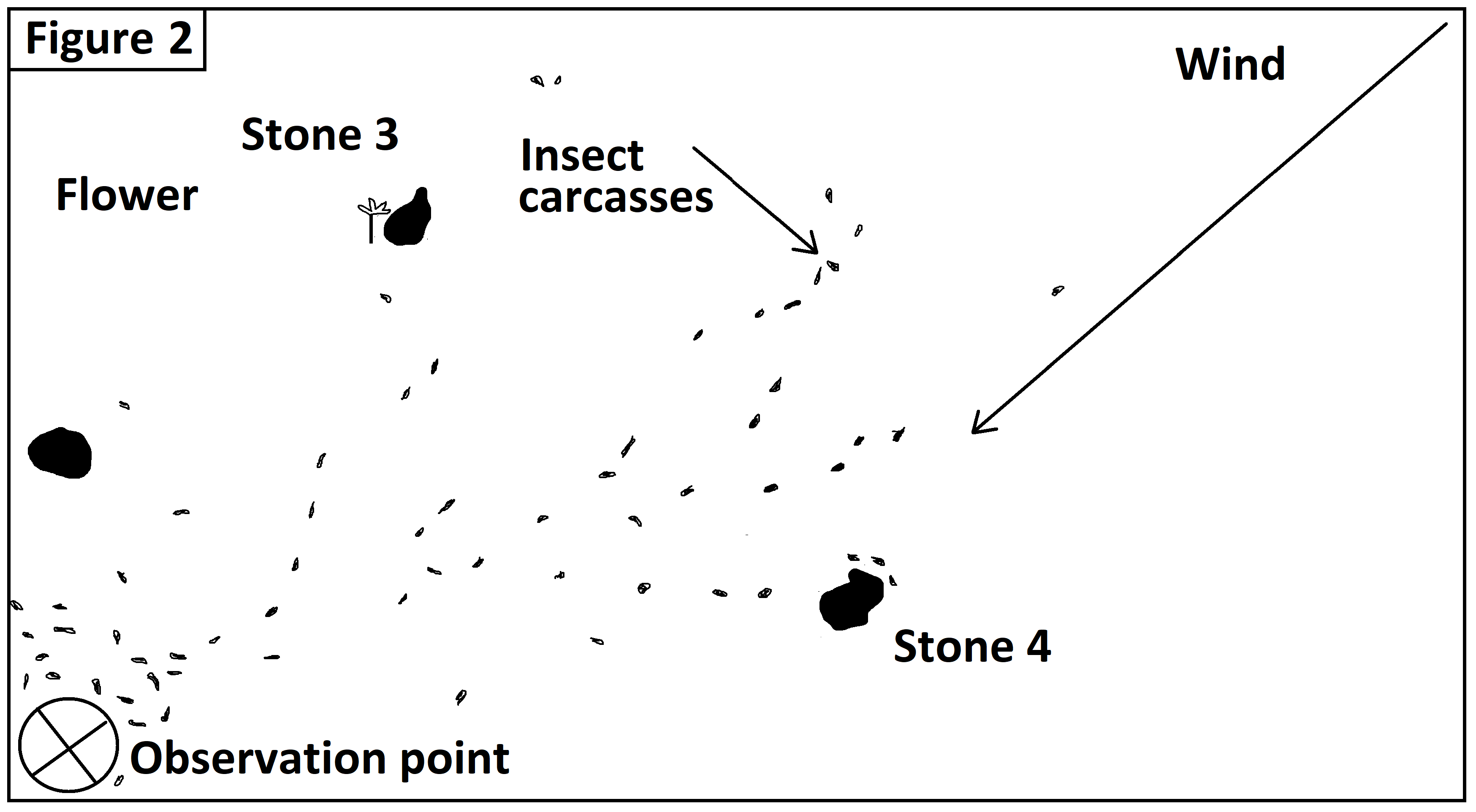

Now, what happened is that some irresponsible humans arrived soon after this observation. What they saw was just a useless and lifeless plot of land. They rearranged the stones by rolling them around. They also took two stones away as memorabilia. What happened next is a mass extinction of the insects and worms living on the land. The flower dried out. The scientists returned next March and they found the plot in the condition shown by Figure 2.

The scientist observed the following:

- Unfortunately, the stones were moved and taken away and this led to the land being more exposed to the wind.

- Exposure to the wind caused the surface erosion to double, at least; this led to the land being more unstable and arid.

- Changes in the land lead to the extinction of insects; numerous exoskeletons of dead insects were noticed; surviving insects must have moved to different plot of land that offers more shadow.

- The flower had a deep and well branched root, so, when deprived of the protection of the large stone, the flower succumbed entirely and dried off; miraculously, the root has sprouted another smaller flowering stem in the protection of a new stone.

- Although the winds are now stronger, the scent of the flower cannot be felt anymore at the observation point due to flower’s new location.

To some, Figure 1 and Figure 2 might seem exactly the same. Who cares about a few stones being rolled over a piece of barren land? However, this illustration shows how even the smallest intervention in our environment always causes significant changes. Every stone on Earth really matters. Even the smallest changes cause micro-tragedies and triumphs, let alone the massive alterations of environment that human beings have been practicing ever since the beginning of the industrial revolution. The most important lesson for humans to learn from this example is that, unless it is a matter of life and death, they have no right to roll even one stone in the most insignificant of deserts.

Maybe you are wondering how this highly intelligent species, which has sent people into the Universe, never realized this painfully obvious interconnection of our environment to everything in it. I believe there were a lot of people who had not realized this basic natural law in time. On the other hand, there were people who were aware of what was happening from day one. Those belonging to the middle class chose to ignore the situation in order not to fall out of their comfort zone. The elite remained silent in order to protect their wealth.

In that respect, there is Figure 3 showing that same one-meter square plot of desert land in 2020. The land is now entirely covered with tarmac (the plot is a part of a parking lot in front of a fast food restaurant situated in the desert). On the tarmac, there are oil stains. The wind brought a used Covid-19 mask that got stuck on the oily surface of the tarmac (the restaurant is closed due to the pandemic).

The Stunning Immorality of 2020 Escapism

The year 2020 was statistically the hottest ever measured. Consequently, the year was marked by extreme weather. We have lived through floods, violent storms, devastating tornados, wild bushfires, and constant earthquakes, just to mention a few examples. This year has seen the biggest retreat of glaciers. According to scientists, there is comparatively little ice left on the planet’s poles. The melting permafrost has caused landslides and craters to collapse in muddy soil. Volcanoes have awakened.

We lost several animal species this year. On the other hand, an enormous quantity of rock was crushed into sand and used for concrete. Thousands of kilometers of pipeline were added to the oil distribution network. While China continues to rapidly devastate its land in order to industrialize its countryside, the four largest and most powerful countries in the world are led by extreme populist maniacs or/and reckless nationalists (I refer to the US, Brazil, Russia and India). The country that has taken on the role of global policeman, the US, has proved to be a society with a very questionable talent for democracy. I have no doubt that, if Stalin could see the state of American society as it is today, he would experience multiple orgasms. Needless to say that America under the current installed president carried on with its dirty wars and incredibly unjust political engineering all over the world. The Brazilian dictator, on the other hand, devastated a large portion of the Amazon rainforest. Russia is led by a person we know more about than our own grandparents – he has been with us that long. He is a dangerous little man, who, astonishingly enough, is sometimes seen as the voice of reason compared to his American counterpart. And India is in a new mode – extreme nationalist full speed ahead. It is, I guess, a matter of luck that I do not need to add the UK and their current leader to this list (and that surely would be an exhausting task) because the UK, and probably soon just the Kingdom of England and those who decide to stay, will become less geo-strategically important than, for example, the Falkland Islands.

In short, although the number and extent of catastrophes does not stand out when compared to many other years in the past, 2020 is a perfect introduction to a story of total ecological collapse. Furthermore, it is the year when the Earth, and especially people from western cultures, was left without the moral and military guidance of the usual superpower figureheads. Regardless of the fact that all the ecological problems that escalated in 2020 were the result of everything that our species has been doing since the 1850s, and regardless of the fact that the previous ‘moral’ guidance of the established superpowers was deeply corrupted and tremendously unjust, I do acknowledge that the year 2020 was quite a shock even for the most pessimistic among us. And I do believe that every next year will pose more and more obstacles for the human species. It is a fairly logical presumption in a world where the word of Chomsky is worth much less than the word of Musk. Whose car is still orbiting the Earth.

Two Objections

Of course, what we will remember 2020 for are not these lurking demons of doom but rather the Covid-19 virus, the clumsy little bugger that stole our dreams and privatized a whole year, maybe even a longer period. With what right and how dare it? In this short and condensed set of observations, I will not give the virus too much time or too much credit, even though it has claimed about 1,835,000 human lives at this writing. I will rather focus only on how humans have decided to blame everything on the calendar year 2020. In the following passages I will consider two principal objections to this massive demonization of 2020 on the internet and in the media, these two objections being number one, the loss of any realistic perspective, and number two, the transfer of responsibility.

The first principal objection, the loss of any realistic perspective, can be observed in the following set of facts: 1. Everything that has happened in 2020 is the result of happenings in previous years. 2. The pandemic situation was something about which scientists had warned us a long time ago. 3. The Western societies revealed how truly spoiled and weak their members are once expelled from their comfort zones. 4. The Covid-19 situation exposed how utterly insensitive Western societies are to the suffering of those outside their cultural circle.

As for the first fact, it seems that humans see 2020 as a period entirely isolated from the rest of history. Perhaps this comes from an ecstatic fear that leads to an urge to wrap 2020 in plastic and just keep silent about it – that I cannot confirm. But it is hard to understand that even educated people believe that 2020 was a ‘year went wrong’ rather than a logical continuation of everything that went on before. And it is even more difficult to understand that they believe that 2021 will bring ‘salvation’. In that respect, those posting on social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, etc., refer to those who lived to see the end of 2020 as ‘survivors’. In their highly delusional manner, they continue to congratulate the survivors for surviving the evil year that decided to crash us all. And, of course, they wish 2020 to die in pain on December 31, midnight, local time. In the forty-two turbulent years I have spent on Earth, I do not think I have ever witnessed such mass hysteria before, even during the war.

The second fact, that we were forewarned, reveals a very interesting feature of human nature: Knowing is not enough for believing, on the contrary, not knowing is often more than enough to believe just about anything. Pandemics are something that followed the human race from the very beginning. Just mentioning the twentieth century and the Spanish flu is enough to illustrate this peculiar relationship between human beings and expansions of deadly viruses. I guess the second half of the twentieth century provided humans with a feeling of false security, which lead to a widespread opinion that ‘this could not happen to us’, despite all the warnings. However, something similar has happened every so often – there were several outbursts of viruses related to the Covid-virus family that caused epidemics in some Asian countries. But that was far from Europe, far from Northern America. Who cared? On TV we watched Asians wearing facemasks and we considered that to be farfetched, weird and nerdish. We still did not believe that this could, and sooner or later would happen to us all. And then there were American catastrophe films dealing with the theme of deadly viruses wiping out our civilization. I guess these films strengthened the idea of global pandemics being a matter of science fiction and undemanding entertainment. And then, in 2020 we are in the midst of it, the whole of humanity in the same boat, in the times of pandemics. After waves of incredible false news, misinterpretations and conspiracy theories both from laymen and, unfortunately, some people of science, humanity is closed off and quarantined. After that, a relatively peaceful summer period followed, and then, with lower temperatures, the virus is back. This is when, starting in October, I first noticed posts on social media which claimed that ‘we cannot wait for this year to finish’ or ‘hold on friends, just a few months left and we are saved’. What would follow were replies of people wishing each other patience and strength ‘to carry on until the end of the nightmare’. Sometimes, more humorous replies would appear, one of such is: ‘2020 the movie, directed by Quentin Tarantino, written by Stephen King, original soundtrack by Yoko Ono.’ All these posts show that the highly probable occurrence of pandemics caught people in 2020 globally unprepared and extremely vulnerable. And that surely is not so much a problem of the calendar year, but rather a problem related to the incompleteness of human perception.

While explaining the third fact, about the global reaction to the pandemics, I have to note that an entirely new genre of lamentation and self-pity was invented in 2020, especially in highly developed and industrialized societies, and that is the Covid-19 lament, of course. Suddenly, people in Western societies felt stripped of their rights and freedoms. They felt isolated, dehumanized, and their work and communication depersonalized. Every description of their existential situation was abundant with words starting with ‘de’. Global destinies derailed. And what happened indeed was that these people were asked to stay at home and avoid social contact so that the Covid-19 virus could be put under control and eventually destroyed. But the fact that Westerners now had to live in isolation for some time suddenly overshadowed, for example, millions of starving children in Yemen. Overnight, drinking coffee with a friend become more meaningful than the fact that there are still hundreds of thousands of refugees on the EU borders freezing in muddy tent camps. This global sentiment was mirrored in social media as well. Memes appeared on Facebook such as: ‘I wish that in 2021 your home, your workplace, and your bar are in three different places.’ Other more ‘spiritualized’ posts appeared, such as: ‘If 2020 taught me anything, then it is the importance of humanity sticking together.’ I cannot help asking myself ‘Then why did 1998 not teach people that illegal invasions of independent countries led to death and destruction, and very little freedom and democracy?’ Or, more importantly, ‘Do human beings really need a pandemic to conclude that they have to stick together?’ All this shows a very ugly aspect of the developed societies: Their members display double standards and two-faced, pathetic emotional ego trips when pushed out of their comfort zones. By posting memes trashing or ‘deeply analyzing’ 2020, they simply restore their self-importance, their comfort, and their feeling of supremacy. And indeed, true are the final verses of T. S. Elliot’s The Hollow Men: ‘This is the way the world ends/ Not with a bang but a whimper.’ We heard a lot of whimpering at the end of 2020, and I suppose the end of our civilization will look equally superficial and detached from reality.

The fourth fact, the capacity for denial, is somehow related to the third one. I will open with one hypothetical or, if you will, poetic question: How can a few months of Covid-19 related quarantine and twelve (to be expected sixteen) months of the Covid-19 situation ever compare to life in the Gaza Strip since 1949? And now in Gaza they have the same degree of isolation, the threat of war, and Covid-19. How can the quarantined world compare to the decades-old situation of (self) isolated Amazon tribes, which are being destroyed, slaughtered, and deported while their forests are being simultaneously cut down and put on the international neo-liberal market? How does the fact that we are not able to drink coffee in our favourite café bars compare to nearly a decade of slaughters in Syria and Yemen? It is important to note that those conflicts were largely fuelled by outside forces – the so called ‘free world’, under the banners of pseudo-democracy, and, their confronting counterparts, the outspoken villains, all of them actually proud of their historical function. It is also interesting to note that the moral, ethical and aesthetic differences between the two opposing outside forces are no greater than the difference between the negative and positive ends of a triple A battery. Were they not entertained enough in Afghanistan, a traditional and once proud society first raped and betrayed by the UK, then irreversibly radicalized by the Soviet excursion and with covert American ‘support’, and then openly massacred by the US? Has Afghanistan not lived in fear and stress for more than a hundred years now? They are talking about, for example, the long-term consequences of the Covid-19 virus on our nervous system. Do we really have any use for gray matter at all if we, as a species, are not able to conclude that the children born terribly deformed today in Vietnam due to the American’s use of Agent Orange more than 45 years ago display more tragic long term consequences in comparison with any aspect of Covid-19 disease? And what about the millions of workers, very often children and minors, quarantined for decades in gloomy industrial (often underground) facilities all around the world, not just Asia, who are paid peanuts in order to produce our precious plastic gadgets? What about the millions of people (self) isolated because of their cast, physical appearance, sexual orientation? Should we promise them a better 2021?

I am always disappointed when this 2020 whimpering finds its way even into the most unexpected of places – highly established cultural circles and institutions. One such example is a text displayed on the building of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) which reads: ‘Please believe these days will pass’, and that instantly went viral. I admit that my reading of this message probably is a bit too narrow. Still, it is my deep belief that such an institution, with such social impact, could have used its influence much more effectively by displaying a radically different message. The message could be, I suppose, the following: ‘Human beings, if you want the bad days to finish, please, stop destroying the planet you live on’. Maybe this is not emotionally and socially engaged enough for the wide masses. But what an opportunity – missed.

The second principal objection to the massive demonization of the year 2020 on the internet and in the media is the immoral transfer of responsibility. If you look closely at the history of human kind, you will see that two feelings existing between humans seem to be essential and constant: fear and guilt. Guilt, of course, being fear’s extremely creative child. Numerous analyses were written about this aspect of the human psyche, and from the point of view of many branches of science. What I am interested in examining in this short overview is the complex system of mechanisms that enable humans to avoid guilt and transfer their objective responsibility onto others, onto deities, natural and supernatural phenomena, and even onto inanimate objects. This complex system of mechanisms (in an extremely and dangerously simplified explanation here but let us take a swing at it anyway) gave birth (just to note the two most prominent examples) to religious beliefs, which outsourced ‘the unbearable human ideal’ to supernatural and nonhuman or semi-human deities, and also to the idea of human societies being organized into units called ‘nation states’, which outsourced the objective responsibility of individuals onto various types of rulers, state institutions and institutionalized pressure groups. This is the reason why even today, in the twenty-first century, we have groups of serious humans with serious university diplomas, followed by serious media, having serious debates on themes such as: ‘Should we allow vaccines produced from aborted embryos?’ and ‘should we have social or authoritarian states?’. These questions in themselves are utterly erroneous. Firstly, the sacred texts of most religions, especially monotheistic ones, claim that land was given to humans to own it, exploit it, and inherit it. Using the Matrix matrix, I will ask you: ‘What if I told you that this is wrong and the source of most of the evils that befall the human species?’ Land is not here for us, we are here for the land (and certainly not as Kennedy intended in his famous speech, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country”, which only confirms the second type of transfer of responsibility exemplified above). Land, that is, nature, is the only true deity. And we are a part of it. In such a society, which would live in a sort of Ubuntu with nature and other creatures, would we have aborted babies at all? My guess is that we surely would not have L’Oreal and Vichy night-care beauty creams. On the other hand, we would have developed science, there is no proof that science and ethical progress stand in confrontation with the philosophy of Ubuntu, au contraire, what I am writing about here is a self-sustainable society, and not a neo-primitive one. If we asked the right questions, our vaccines would be different, their production, development financing and distribution would be radically different, and, finally our diseases would be different and appearing in different historical periods as compared to the ones that we have now.

Secondly, the question of what kind of state we should live in is in itself useless unless another question is thoroughly answered first: Why do we need national/political states at all? In my deep belief, the essential message of every state to its subjects is the following: ‘People, you are incapable of organizing your lives without the monitoring of a higher authority. Hence, you have to give us, the state and its representatives, the power to entirely organize your lives. However, the organization is costly, and you are obliged to finance the state on your own.’ Is this the ultimate ideal for humans? What about societies organized in cooperative interest groups divided by natural phenomena, such as mountain ranges, large rivers, seas, etc. (rather than by ‘national/linguistic/religious borders’), groups distributed in a way that makes their existence on a certain plot of land sustainable over time, and, finally, groups that are at any given moment able to help other groups that might be encountering existential problems?

Pure utopia, most scientists and layman would say. On the other hand, they are offering you either free market economies and abusive societies which will go on exploiting the planet until they irreversibly destroy the last square meter of it, or societies that are a bit ‘less free’ but equally aggressive to the nature. Instead of a ‘naïve utopia’ they offer you destruction, lies, arrogance and, consequently, extinction.

My firm opinion is that humans will never realize that a radically different type of society is not at all a utopia (or does the fact that such societies are currently beyond human shared consciousness actually confirm them as utopias?). They will never start asking the right structural questions. Even those for whom my words make sense, and they are numerous (after all, what I am writing here is no novelty – philosophers have considered the reality of the so-called intuitive societies ever since ancient times) will ignore their own knowledge because of greed and short term personal gain. My prediction for civilization, which the reader might perceive as overly religious (or Biblical, at least), is that it will be abruptly recycled, almost surely in a year starting with number 2 (to remain loyal to a Baba Vanga style binary logic-based prediction).

Instead of respect, love and care for nature, humans will press on with their transfer of responsibility. Covid-19 spread, especially in industrialized areas – blame it on 2020. Half of humanity in quarantine – blame it on 2020. 1,835,000 deaths – blame it on 2020. Ice melting – blame it on 2020. Melted ice temporarily cooling the oceans – blame it on 2020. Ocean levels rising – blame it on 2020. Oceans and continents heating exponentially after most of the ice has been lost – blame it on 2020. A global climate change – blame it on 2020. Activated tectonic plates – blame it on 2020. Destroyed and disappearing biospheres – blame it on 2020. The rise of viruses – blame it on 2020. The consequent collapse of economies – blame it on 2020.

We, humans, had nothing to do with it. We were merely victims of a very, very evil calendar year. I will not continue with my subsequent thoughts because I am now unable to sustain seriousness and be polite (on that note, apologies for the Baba Vanga remark).

Everything I wrote so far is to prove that human beings, as a species that builds its perception of morality on a set of lies and half-truths, have entirely lost their compass in 2020, and began to behave like insulted children. By posting vindictive content about a calendar year, humans have disclosed a very alarming and sad truth about their intrinsic nature, a deep immorality and an utter lack of objective thinking. Humans globally have fashioned an effigy out of a calendar year, a doll they are about to burn at the main venue of their vanity fair, hence releasing an unknown amount of dangerous polluting gases into the atmosphere. And then we will go en masse to see our psychotherapists. I simply must say this: God, what a repulsive species!

What still shocks me is the incredible fact that even people who are aware of the ecological problems humans have created still decided to take it out on 2020 and join the viral public lynch. I really hope they felt better after doing that, and that their lives and the prospects of survival look much better now in the first week of 2021. Finally, I can only agree with one of the more pathetic viral memes stating that ‘in 2020 we at least have not met Godzilla.’ Indeed, I do not think that anyone spotted Godzilla.

In Conclusion: Have a Great 2021!

Do not worry. Let us continue with deceiving ourselves. New year – new start – new me! The year 2021 will be the year of revelation and salvation. The time when we will triumphantly look back on the evil 2020 with scorn and disgust. The year when we will still post online memes and jokes insulting 2020, only this time – we will be in control again.

On the other hand, if this approach does not work out, humans, we will be in a great trouble. Just remember another viral meme, the one showing three tsunami waves, the smallest one being Covid-19, the larger one being the collapse of the global economy, and absolutely the largest one being climate change. To put it simply, humans will probably die out soon, or at least most of us. But even in the worst scenario, maybe everything is not lost. Recently I read an article about scientists on three continents agreeing that some primates have entered an early stone age of their own. This news was also published on BBC Earth in 2015 (just a note – how evil was 2015?), claiming that some chimpanzees and other primate species had indeed entered a stone age, and that there was evidence of 4,300 year-old stone tools used by chimpanzees. My suggestion is that humans start preparing an exhaustive library (printed on durable paper or, perhaps stone or golden plates) about their own civilization, and in a code that chimpanzees will be able to understand after a long period of time (perhaps a cast of chimpanzee nobility should be raised now, to be trained in the language used for instruction on human civilization). That way, chimpanzees will see where humans erred, and what went wrong. That should empower them to avoid committing the same mistakes. The first sentence in that exhaustive library should be: ‘Respect every stone!’ The second sentence should be: ‘2020 was a very evil year!’ Maybe chimpanzees will be more successful bearers of the human existential burden. Or maybe they will totally misinterpret our messages and go extinct.

I just wish that we could understand the year 2020 as our strict teacher, rather than our enemy.