The objectives of reforming sub-levels of the public sector have historically been driven by the will and need to amalgamate municipalities. The reasons given for amalgamating have primarily been size-efficiency and capacity, as well as quality and quantity in services. This is shown, for example, in a recent study of selected European countries where these objectives are of high importance with regard to amalgamations in 11 European countries (Steiner et al., 2016). Baldersheim and Rose (2010) have described these objectives as “the consolidationist argument”. The basic argument is that, due to scale economies, increased size of political-administrative units will lower average costs (i.e., cost per capita) of providing municipal services and therefore increase the capacity to redistribute economic and organizational resources more effectively. What this means is that increased size yields lower average cost, which gives opportunities to provide services of more quality and quantity and distribute them more equally within all neighbourhoods and between neighbourhoods.

Whether these objectives are realized after amalgamation in a new municipality is, however another question which has often been hard to answer in empirical studies. In the study of 11 European countries by Steiner et al. (2016) the most important outcomes of amalgamations tend to be improved service quality and to some extent cost savings. Case studies evaluating the impact of municipal amalgamations seem to be rare. However, Eythórsson and Jóhannesson (2002)[1] evaluated the impact of 7 different amalgamations out of a total of 37 municipalities in Iceland from the 1990’s. The evaluation covered various aspects such as democracy, administration, services, economic development and cost-efficiency. Among other things, their results indicated that services tended to improve and cost-efficiency tended to be realised, at least to some extent. Important aspects in this context were found to be equality between different parts of the municipality, as well as time from amalgamation. Even though, in general, quality and quantity in services increased after amalgamation, this did not seem to be the case for all parts or neighbourhoods of the municipality. People and local leaders in the more peripheral and less central parts were more discontent with the development of services in the new municipality. The time perspective seemed to matter, at least in some service fields. In the case of Iceland, there was some evidence that improvements in economic development and in infrastructure took time and that no positive signs could be detected until at least five years after the amalgamation.

These almost 20 year old results indicate that the impact of municipal amalgamations often turns out to be more complex than general approaches may show. Therefore, we find it relevant to analyse newer material to try to determine whether this is the case with amalgamations a decade or decades later – in times when lessons could have been learned from previous cases in order to try to prevent inequality in service provision. This article attempts to answer the question what impact municipal amalgamations have had on municipal services, especially looking at service quality, service capacity, service efficiency and equality in services between the centre and the periphery in the municipality. The analysis is based on material from two separate research projects: firstly, from 2015, survey among elected local politicians in Iceland and, secondly, data from a survey conducted in 2013, where the respondents were citizens in eight amalgamated municipalities, which had been amalgamated in and around the middle of the first decade of the 21st century.

The municipal level in Iceland

Municipalities in Iceland have a long history, dating all the way back to the 11th century. When the Danes took control over Iceland in 1662, they whittled down the autonomy of municipalities and then totally abolished them by law in 1809. Later on, in the 19th century, when the Icelanders began asserting their rights of independence, the local government system was re-instituted by law, in 1872, this time including a regional governmental level – Amt (county, administrative province), similar to an earlier structure in Denmark which was reformed in 2007. This regional experiment was not successful, and the Amts had already been abolished in 1904.

The main historical pattern of structure indicates that the number of municipalities gradually increased slowly until the middle of the 20th century when it reached a peak of 229 municipalities, after which a slow decrease set in, but not significantly until after 1990. Since 2013 the number of municipalities has remained 74.

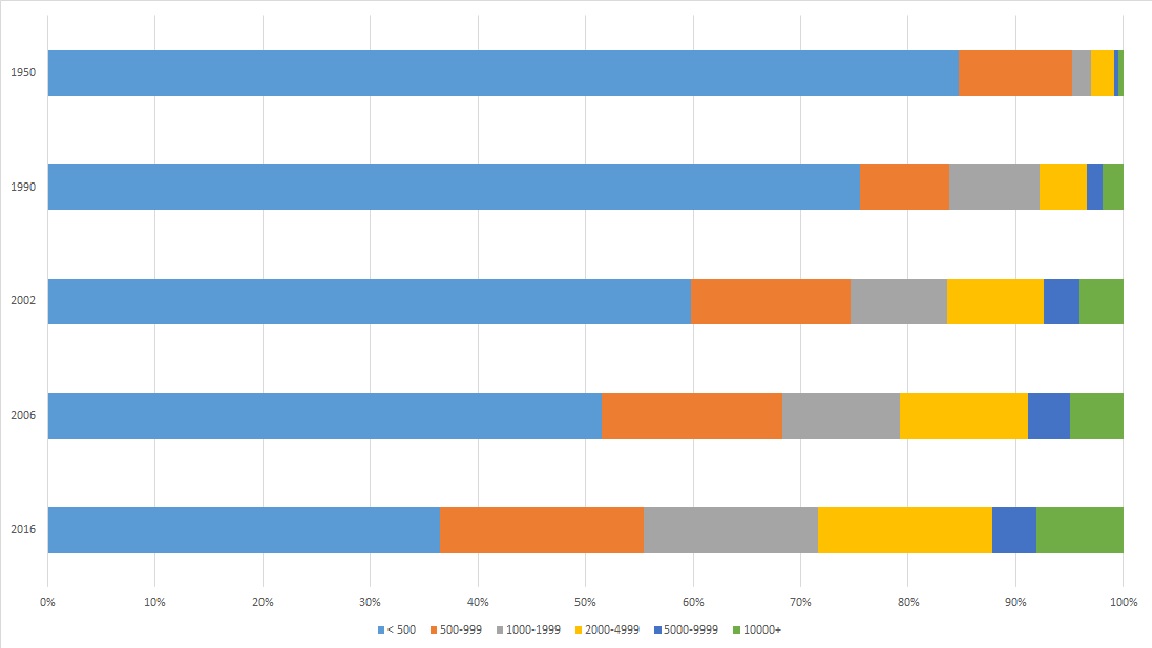

The rapid changes since 1990 were directly and indirectly facilitated by two referenda on municipal amalgamations – the first in 1993 and the second in 2005 – and their implications. The referendum in 185 municipalities in 1993 (especially) and the referendum in 66 municipalities in 2005 contributed to the reduction of the number of municipalities from 196 in 1993 to the 74 today. However, this reduction has not managed to change the main characteristics of the municipal structure – small municipalities and a relatively fragmented system with an average population of approximately 4,500 and a median of about 900. This is illustrated in figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Figure 1. The patterns of municipal structure in Iceland 1950 – 2015.

The figure shows a fragmented municipal structure, despite the reduced number of municipalities by almost 2/3 in two decades. From the beginning, amalgamations were meant to strengthen the municipal level by producing larger local units which could take over extensive new functions from the state. The partial failure to carry out a complete reorganisation of the structure led to a setback; thus, this way of making progress was defeated to a certain extent (Eythórsson 1998; Eythórsson 2009).

Twice during these twenty years, extensive functions and responsibilities have been decentralized to the municipal level, the primary school in 1996 and the handicap services in 2011. In the case of the primary school, the heavy burden of running the schools for many of the smallest or smaller municipalities pushed them into amalgamations. As far as the handicap services were concerned, problems were only solved by means of inter-municipal cooperation, since a large majority of the municipalities did not have the capacity to run these operations by themselves.

Iceland has a two-tier administrative system, national and local. A regional level as an elected instance is absent. Therefore, the lower level is ill-equipped to take care of tasks allocated to the median instance in some of the other Nordic countries. While the local level in the Scandinavian countries such as Denmark, Sweden and Norway is responsible for 60-70 percent of public expenditure, the local level in Iceland is only responsible for about 30 percent.

The local government system is characterized by a high proportion of small municipalities. More than half of them have a population of less than 500 while just above 10 percent have more than 5000. More than half the municipalities have limited capacity to provide services cost-efficiently and with reasonable quality. That is, at least, what the critics have said when they have advocated more municipal amalgamations (Eythórsson, 2014).

This has been reduced to 74 in more than 80 different amalgamations, almost all of which were voluntary. The largest years, counted in number of amalgamations, were 1994 and 1998, when there were 13 and 12 amalgamations respectively (Karlsson, 2015).

As for a description of the tasks and main premises of the municipalities in Iceland, the main tasks are the following:[2]

- Education (primary school, kindergartens and music schools)

- Social services (except elderly care)

- Youth leisure and sports

- Health care (health care centres)

- Culture

- Fire department and public disaster protection

- Hygiene

- Planning and construction

- Traffic and transportation

- Environmental affairs

- Industrial affairs (economic development etc.)

Education is by far the largest expenditure post, followed by social services, and youth leisure and sports, which are also considerable posts. Local government expenditures constitute around 30 percent of total public spending – which is low in comparison with the other Nordic countries where the local level expenditure is between 60 and 70 percent. Municipal revenues are mainly through Income tax (58%) and the rest is through Real estate tax (12%), contributions from Equalisation fund (12%) and other income (18%).[3]

Amalgamations and services. Some theoretical reflections

The so called consolidationist argument on the impact of municipal amalgamations claims that increased size of political-administrative units will lower costs of providing municipal services and increase capacity to redistribute economic and organizational resources more effectively (Baldersheim & Rose, 2010). This leads to, or at least can lead to, improved service quality. Even though this is a widespread argument, only few studies exist on the outcome of such an approach, at least in the case of the Nordic countries. However, the consolidationalist view was clearly stated before the big amalgamation reform in Denmark in 2007 (Kjær and Mouritzen, 2003). In an Icelandic evaluation study on amalgamations in the 1990’s by Eythórsson and Jóhannesson (2002), some indications of this causal connection appeared, but they were not fully confirmed by the results. However, the authors found that all economic gains in terms of lower cost were used to improve services. In a new Norwegian anthology on municipal reforms (Klausen, Askim & Vabo eds., 2016), Borge puts this view forward in the context of Norwegian municipal amalgamations. Comparatively, provision of public services is likely to generate scale economies in step with agglomeration economies and thus lower average cost. Even in a bigger European context this has been investigated. In a study on the outcomes of municipal amalgamations in 15 European countries Steiner (et.al) found that one of the absolutely most important outcomes from municipal amalgamations was “Improved professional quality” (Steiner (et.al.) 2016 pp. 36-37).

Some findings connect gain of scale economy and agglomeration with service improvements. Rosen and Gayer (2008) suggested that scale economies were present in public services such as fire departments and libraries. Similar results were addressed in a general study for Britain, where this seems to be the case in the provision of health care services, water supplies, and telecommunications (Burridge, 2008). Furthermore, scale economies are present in primary and upper secondary schools, both regarding overhead and teaching cost. However, diseconomies of scale became apparent in teaching when quality was taken into account. Similar findings were obtained by Duncombe and Yinger (2007) and Duncombe et al. (1995). It has also been argued that an urban population contributes to social benefit in terms of agglomeration economies. „In the presence of agglomeration economies, average production cost is generally lower, which in knowledge-based industries increases profits, returns to shareholders and the real wages of highly skilled labour“(Karlsson, 2012, pp. 125–126). Thus, agglomeration economies are similar to scale economies in being a source of economic growth and higher welfare.

Results from empirical literature do not all point in the same direction, both in national and international comparisons. A result suggesting a net positive return following an amalgamation because of scale economies, might be detected in something other than lower average cost, such as better services. Better or more services might, however, either be delayed or not provided to part of the population.

The centre-periphery dimension

Both citizens and political elites in municipalities often tend to oppose amalgamation reforms, not least if the reforms are initiated by central government – from above. But there is a difference in this between large and small municipalities, on the one hand and between smaller, peripheral and larger central municipalities, on the other hand. Results from studies on both Swedish and Icelandic municipalities have shown that the strongest explanatory variable for resistance against amalgamation is each municipality’s expected status in the new/potential municipality (Brantgärde, 1974; Eythórsson, 1998). The potential loss of status and power is something that does not seem to be acceptable for either citizens or local leaders in municipalities with little chances of getting the central place status. In this sense there are centres and peripheries within the new municipalities. This different positions can easily impact attitudes towards the service provided in a new municipality – those who feel they have lost status and power as a consequence of an amalgamation might also have similar attitudes to the services, both service quality and quantity. The study by Eythórsson and Jóhannesson (2002) showed precisely those patterns.

The time perspective

The time factor is known in economic theory. The rigid behaviour of individuals or institutional units can create a time delay in the outcomes of economic events, such as in the case of price elasticity in the short versus the long run (McGuigan, Moyer, and Harris, 1999, p. 105). Therefore, the impact of inputs might have to wait to show up and be realized by citizens in the community.

The time perspective can be play an important role in the context of a municipal amalgamation and its impact. Whether the amalgamation was implemented a short time ago or a long time ago, is in many cases a question of the opportunity for reorganisation to come into effect. This has for example, been found in evaluations of amalgamations. Eythórsson and Jóhannesson (2002) discovered a time-related impact in their evaluation of seven different amalgamations in Iceland in the 1990´s. The increased service deliverance capacity gained by the amalgamation and to invest in infrastructure was found to have an impact on economic development, but the improvements often did not begin to take effect until 5-10 years after the amalgamation.

Local leader survey in 2015

The data we use in this part of the empirical study are from a net-survey sent to the whole population of elected local councillors in Iceland in the summer 2015. This was a part of the research project „West Nordic Municipal Structure“.The same survey was even sent to elected local councillors in Greenland and the Faroe Islands (Eythórsson et al., 2015). Little more than half – 263 out of a total of 504 councillors answered in the Icelandic part and they build the database we are using. In our analysis, we only use answers from councillors in municipalities, which have been part of an amalgamation for the past 20 years. In the Icelandic case, this means less than half of all municipalities. Table 1 below shows the age and gender distribution among those who participated in the survey and compares it with the actual distribution in the population of all local councilors in Iceland.

TABLE 1

Table 1. Participation in the 2015 survey among Icelandic local councillors by gender and age.

Looking at age the distribution is very similar which indicates that there is quite equal respresentation in the survey. When it comes to gender there is a little deviation – women participated more in our survey than men did. The difference is however not great.

In the survey, we asked several questions on municipal amalgamations and their impact on services and administration. In this article, we present a fourfold analysis. Firstly, we asked whether amalgamations had made the service provision more efficient. The second question was about service quality, whether it was higher or lower; thirdly, we wanted our respondents to evaluate whether service quality was equal in all neighbourhoods (areas) in the municipality. The fourth question related to a general evaluation as to whether services and administration were more professional after the amalgamation.

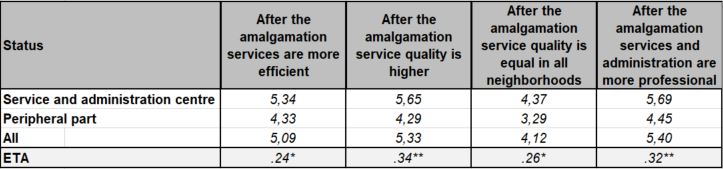

Status/position and centre/periphery

The following table clearly indicates how answers from municipal service centres and peripheral parts differ significantly. Here we see far more differences than in table 2, where we analysed perceptions of services by the time since amalgamation factor. Status or position has a clear impact on local leaders’ perception of service development. In all four questions, the difference between centre and periphery exceeds 1 on the 1 – 7 scale. However, in three questions, the scores are quite high in both groups, which tells us that efficiency, quality and professionality has increased with amalgamations as perceived by the leaders. In the question on equal quality, the pattern is the same as in others, but the scores are lower. In the centres, the score is just above the middle of the scale (4.37), but in the peripheries it is well below (3.29).

TABLE 2

Table 2. Icelandic local councillors’ attitudes towards four statements on the impact of municipal amalgamations on services/administration by status/position. (Means on a 1 – 7 scale. N = 86 – 91).

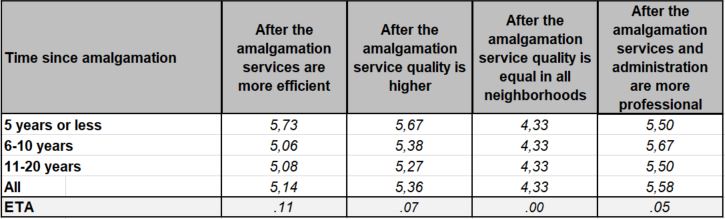

The time perspective

Therefore, with this in mind, we looked at whether the time factor could have an impact on local councillors’ perceptions of services. In table 1 below, we see the results. In three of the questions the scores are rather high – well above 5 on the 1 to 7 scale, which indicates a positive impact of the amalgamation. The differences in scores between three time periods do not show any significant variations and the correlation coefficients show little and insignificant correlation. The only question with slightly divergent results is the one about equality between neighbourhoods in service quality. The local councillors gave more split responses to that statement – the total mean is in the middle of the 1 – 7 scale. The scores are not at all different between periods so the time factor is not present in that question either.

TABLE 3

Table 3. Icelandic local councillors’ attitudes towards four statements on the impact of municipal amalgamations on services/administration assessed by time since amalgamation. (Means on a 1 – 7 scale. N = 111 – 117).

To conclude on this, the time factor does not have any impact on how the local councillors perceive the development of service quality after amalgamations.

To sum up, in general, local leaders evaluate the impact of amalgamations on services as being positive but leaders in the peripheries are significantly less positive than their colleagues in service and administrative centres. Their evaluation also shows us less confidence in service quality being equal in different parts of the amalgamated municipalities.

The citizens’ views

Since the above survey is from an elite study – that is, shows evaluations of elected politicians, we want to contribute with results on the citizens views. The results we present here are from questions we sent out to citizens over 20 years of age in eight municipalities in Iceland, which had been amalgamated from a total of 22 municipalities. This was sent out in spring and summer 2013. This was not based on a random sample – we used the snowball method by distributing to Facebook friends in respective municipalities, asking them to forward the messages to friends in their municipalities, aged 20 years or above. This sampling method does of course not allow us to generalize from the results. Nonprobability sampling methods are used in quantitative studies where researchers are unable to use probability selection methods (Schutt, 2012). In our case, lack of funding prevented us from being able to make a probability sampling. However, we believe we can accept these results as an indication. Our main aim is to try to identify whether the results differ from those in the leader survey. Thus, we wish to present some results from this citizen survey, emphasizing, at the same time, that they have to be used with caution, avoiding excessive generalization.

The database consisted of totally 911 answers from citizens aged twenty or above, in the eight selected municipalities, since they had only a few years before gone through an amalgamation.[4] The respondents were asked questions on most service areas covered by the municipalities and whether they thought the services had improved or deteriorated since the amalgamation. We selected the results from questions on four different service areas, as well as the question on services in general. In this data set, we do not have the “time since amalgamation” variable but instead the “centre-periphery” variable, which is constructed the same way as in the leader survey from the section above.

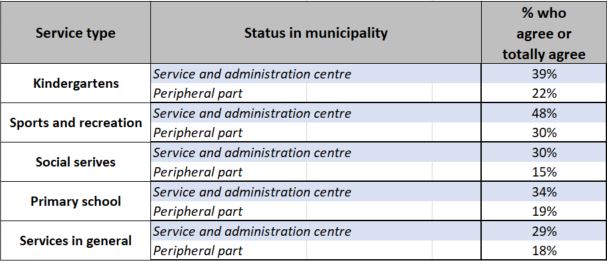

Citizens, services and centre-periphery

Our first analysis is of the citizen’s views is in their evaluation of the development of services in general after the amalgamations. Here we found clear differences between the views in centre and periphery where 29 percent in the centres agreed or totally agreed on that the services had improved and not more than 18 percent in the peripheries had the same opinion. As many as 58 percent in the peripheries disagreed or totally disagreed on this – only 26 percent in the centres. This can’t be seen otherwise than showing obvious differences between centre and periphery where the impact of amalgamation on services is clearly seen as more negative in the peripheral parts of the municipalities.

When looking at the specific service areas we first pick out the two posts who are largest with respect to the total municipal budget primary school and social services, and, additionally, two voluntary posts which can be said to be among the most common and important sectors, sports and recreation and kindergartens.

We begin by looking at primary schools. Here we see the same pattern as in the evaluation of services in general but here the differences between centre and periphery are not as marked. Still, the evaluation shows divided views and even in the centres only 34 percent agree on that services have improved since the amalgamation while 19 percent in the peripheries do. Quite a number – more than 40 percent do not see any change after the amalgamation. The difference is apparent and this indicates that the centre and the periphery evaluate this differently.

Next, we look at social services and here we see a pattern very similar to that of the primary school services. The people in the peripheries evaluate the change more negatively than people in the centres. 30 percent in the peripheries agree on that the services have improved, while only 15 percent in the peripheries do. We see a pattern here, the difference between centre and periphery is apparent.

Sports and recreation is a voluntary service post but nevertheless an important part of the modern living conditions most municipalities in Iceland try to provide for their citizens. Here, we continue to see similar pattern as in the other servies; people in the peripheral parts evaluate the development in this kind of services more negatively than people in the centres. Though, the views are in general rather positive compared with the others but still they differ between the central and peripheral parts.

The last question we look at relates to kindergartens – another voluntary service post but still necessary and most, if not, all municipalities try to provide it. The results continue to show us similar patterns – both negative and positive evaluations but more negative in the peripheries. A considerable proportion of the people in the peripheries see improvement in this post.

In table 3 we show the summarized differences between centre and periphery in all the services we asked about. Lets keep in mind that these figures just show us tendencies and we are not allowed to generalize too much due to our sampling method.

TABLE 4

Table 4. Overview of the Icelandic citizen’s views on the impact of municipal amalgamations on the services by residence in eight amalgamated municipalities.

To sum up our results from the 2013 study, we conclude that the patterns we got are very similar to those in the local leader’s survey. The general pattern is that people coming from and living in the administrative and service centres are more positive towards the impact of amalgamations on services in general as well as on four selected service posts. Those who live the peripheral parts seem to be more negative, but we can hardly conclude from our material that there exists any deep discontent. It is interesting to see that the general evaluation of services seems to be more negative than that of specific service areas. In this section, we have to keep in mind that our analysis is grounded on a snowball sampling method, which limits our possibilities to generalize. Still, we see similar patterns here as in the analysis of survey results among local leaders where we made a total sample.

Conclusion

This article has attempted to analyse material from two separate databases from surveys where the respondents were asked about their perceptions of the impact of municipal amalgamations on the quality of services in their own municipality. The survey was conducted among elected local politicians in Iceland (2015) and the other research among citizens in eight municipalities, amalgamated in and around the middle of the first decade of the 21st century. In our analysis we have mainly been concerned with the possibilities of varying impact between different parts of the municipality – the centre and peripheral areas.

The results from the local leader survey have shown us that the time perspective appears not to matter with regard to perceptions of how municipal services are evaluated after amalgamations. On the other hand, the local leader survey shows significant differences between perceptions in the centre and the periphery. In all four questions asked about services, local leaders from the peripheral parts evaluate the impact more negatively than their colleagues in the centres, where services and administration are more concentrated. However, generally, the local leaders evaluate the impact of amalgamations on services as being rather positive. The analysis also shows us that service quality does not seem to be equal in different parts of the amalgamated municipalities. The centre-periphery divergence is apparent, though without any dramatic differences. Those are the most significant results gleaned from the local leader survey.

Results from the 2013 citizen survey have to be handled more carefully. As we have underlined earlier in the article, the sample in the citizen survey was non-random. Therefore, no generalisations can be made on the ground of the results. We are only allowed to talk about indications at the most. Although the questions in the citizen study were not exactly the same as those used in the local leader survey, they also focused on services and how the respondents perceived their development after amalgamations. To put it briefly, the results from the citizen part point in the very same direction as those from the leader survey. There is, for example, a significant difference in how people in peripheries and in the centres evaluate the development of services after an amalgamation. All the tables above show people in the peripheral parts as being more negative or less positive than those in the centres. However, the perceptions seem to be mixed. In some cases, people in the peripheries see a positive outcome of an amalgamation and in others a negative outcome. The difference between the two groups is largest by far in the question where people are asked to evaluate services in general. When asked about specific services such as primary schools, kindergartens, social services and recreation and sports, the same pattern is also apparent but it is less evident than in the general evaluation. Again, it should be noted that the results from the citizen survey support the other results. Thus, there seems to be a good match between how citizens and the local leaders perceive the development.

The research project by Eythórsson and Jóhannesson (2002) returned a similar pattern. However, in that case only social services and primary schools were evaluated. In this study we have broadened the range and showed that when looking at several large and important municipal service areas, the rift between centre and periphery is very much in evidence. As for municipalities entering into amalgamations in the role of little brother, it is probably sensible to conclude that in those kinds of reforms you win some and you lose some.

References

Baldersheim, H., & Rose, L. (2010), Territorial Choice: Rescaling Governance in European States, Baldersheim, H. & Rose, L. (eds.) (2010). “Territorial Choice. The Politics of Boundaries and Borders”. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Borge, L-E. (2016). Økonomiske perspektiver på kommunesammenslutninger [Economic perspectives on municipal amalgamations], Klausen, J. E., Askim, J. & Vabo, S. I. (eds.) (2016). ”Kommunereform i perspektiv” [A perspective on municipal reform]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Brantgärde, L. (1974). Kommunerna och kommunblocksbildningen [Municipalities and municipal amalgamations], Göteborg: Göteborg Studies in Politics 4.

Burridge (2008) “Scale and efficiency in the provision of local government services”. International Journal of Business Performance Management, 10, 99-107.

Byrnes, J., & Dollery, B. (2002), “Do Economies of Scale Exist in Australian Local Government? A Review of the Research Evidence”, Urban Policy and Research, 20(4), 391 – 414.

Dollery, B., Byrnes, J., & Crase, L. (2007), “Is Bigger Better? Local Government Amalgamation and the South Australian Rising to the Challenge Inquiry”, Economic Analysis and Policy, 37(1), 14.

Dollery, B., Crase, L., & Johnson, A. (2006), “Australian Local Government Economics”, The Economic Record, The Economic Society of Australia. Sidney: UNSW Press.

Duncombe, W., & Yinger, J. (2007), “Does School District Consolidation Cut Costs?”, Education Finance and Policy, 2(4), 341-375.

Duncombe, W., Miner, J., & Ruggiero, J. (1995), “Potential cost savings from school district consolidation: A case study of New York”, Economics of Education Review, 14(3), 265-284.

Dur, R., & Staal, K. (2008), “Local public good provision, municipal consolidation, and national transfers”, Regional Science and Urban Economics, 38(2), 160-173.

Eythórsson, G. T. (1998), Kommunindelningspolitik i Island. Staten, kommunerna och folket om kommunsammanslagningar[Politics of municipal divisions in Iceland. Perspectives of the state, the muncipalities and the inhabitants regarding municipal amalgamations]. Göteborg: CEFOS.

Eythórsson, G. T. (2009), Municipal amalgamations in Iceland. Past, present and future, Baldacchino, Greenwood & Felt (eds.): “Remote Control. Governance Lessons for and from Small, Insular, and Remote Regions”. St. John´s: Iser Books.

Eythórsson, G. T. (2011), Kommunsammanslagningar på Island. [Municipal amalgamations in Iceland]. Ivarsson, Andreas (ed.): ”Nordisk kommunforskning. En forskningsöversikt med 113 projekt” [Nordic municipal research. A survey of 113 research projects]. Göteborg: Förvaltningshögskolan.

Eythórsson, G. T. (2012), Efling íslenska sveitarstjórnarstigsins. Áherslur, hugmyndir og aðgerðir [Strengthening the Icelandic municipal level. Focal points, ideas and actions], Stjórnmál og stjórnsýsla 8(2)., 431-450 http://www.irpa.is/article/view/1187

Eythórsson, G. T., & Jóhannesson, H. (2002), Sameining sveitarfélaga. Áhrif og afleiðingar [Municipal amalgamations. Impacts and consequences]. Akureyri. RHA.

Eythórsson, G. T., Gløersen, E., & Karlsson, V (2014), West Nordic municipal structure. Challenges to local democracy, efficient service provision and adaptive capacity.

Akureyri: University of Akureyri Research Centre. http://ssv.is/Files/Skra_0068629.pdf

Eythórsson, G. T., Gløersen, E. & Karlsson, V. (2015), Municipalities in the Arctic in challenging times. West Nordic local politicians and administrators on municipal structure, local democracy. Service provision and adaptive capacity in their municipalities. Akureyri: University of Akureyri.

Fujita, M., Krugman, P., & Venables, A. J. (1999), The spatial economy: Cities, regions, and international trade. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Houlberg, K. (2011), “Administrative stordriftsfordele ved kommunalreformen i Danmark – sandede eller tilsandede” [Aministrative economies of scale in local government reform in Denmark – realised or exaggerated]. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 15(1), 20.

Jordahl, H., & Liang, C.-Y. (2010), “Merged municipalities, higher debt: on free-riding and the common pool problem in politics”. Public Choice, 143, 16.

Karlsson, V., & Jónsson, E. Á. (2011-2012), “Meðalkostnaður íslenskra sveitarfélaga, fjöldi íbúa og sameining sveitarfélaga”. [Average costs of Icelandic municipalities, populations and municipal amalgamations]. Bifrost Journal of Social Science, 5-6, 73-85.

Karlsson, V. (2012), Transportation improvement and interregional migration. (Ph.D.), University of Iceland, Reykjavik.

Karlsson, V., & Agnarsson, S. (2016), Kostnaður við íslenska grunnskóla [Operational cost of Icelandic compulsory education], Paper presented at the conference Rannsóknir í félagsvísindum [Research in the Social Sciences] XVII, Reykjavík. http://skemman.is/stream/get/1946/26366/59617/1/HAG_Vifill_Sveinn.pdf

Karlsson, V. (2015), “Amalgamation of Icelandic Municipalities, Average Cost and Economic Crisis: Panel Data Analysis”. In: International Journal of Regional Development, 2,(1), 17-38)

Kjær, U., & Mouritzen, P. E. (eds.) (2003), Kommunestørrelse og lokalt demokrati [Size of municipalities and local democracy]. Odense: Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Klausen, J. E., Askim, J., & Vabo, S. I. (eds.) (2016). Kommunereform i perspektiv [A perspective on municipal reform]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

McGuigan, J.R., Moyer, R.C., & Harris, F.H. (1999), Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategy, and Tactics. Boston. South-Western College Publishing.

Myrdal, G. (1957), Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. London: Methuen & Co.

O’Sullivan, A. (2009), Urban economics (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill / Irwin.

Rosen, H. S., & Gayer, T. (2008), Public Finance (8th. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Rouse, P., & Putterill, M. (2005), “Local government amalgamation policy: A highway maintenance evaluation”. Management Accounting Research, 16(4), 438-463.

Schutt R. K. (2012), Investigating the social world: the process and practice of research. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

Steiner, R., Kaiser, C., & Eythórsson, G. T. (2016), A Comparative Analysis of Amalgamation Reforms in Selected European Countries. In: Kuhlmann, S. & Bouckaert, G. (eds.): “Local Public Sector Reforms in Times of Crisis. National trajectories and international comparisons”. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Tyrefors Hinnerich, B. (2009), “Do merging local governments free ride on their counterparts when facing boundary reform?” Journal of Public Economics, 93(5-6), 721-728.

Endnotes

[1] See also in Eythórsson (2009) and Eythórsson (2011).

[2] Cf. http://www.samband.is/media/skyrslur-og-utgafur-hag–og-upplysingasvid/Enskur_Baeklingur_mars_2016.pdf

[3] Local Governments. Facts and figures. http://www.samband.is/media/skyrslur-og-utgafur-hag–og-upplysingasvid/Enskur_Baeklingur_mars_2016.pdf

[4] In the eight municipalities there were about 15500 inhabitants in 2013. Roughly 70% of them were 20 years or older. That means that our 911 respondents are about 8-9% of that population.