Introduction

The paper focuses on Norwegian minke whale whaling from 2006 until 2015, and seeks to assess the level of transparency in modern Norwegian whaling. Although Norway has been hunting the common minke whale since medieval times,[1] the timeframe 2006-2015 was chosen in order to be able to include and analyse the latest regulations and information concerning Norwegian whaling, rather than providing a historical account. Furthermore, at first glance the Norwegian Government appears to be very transparent about the whaling practices, and the authors wanted to understand whether it is indeed transparent.

This paper will use the definition of transparency provided by Rachael Lorna Johnstone and Hjálti Ómar Ágústsson, as these authors evaluate transparency according to the ease of accessing information and the quality of this information.[2] This type of evaluation of transparency fits best with the type of research conducted in this paper. Most of the research was conducted by analysing various Norwegian Government websites, documents, and other information available online. Additionally, phone calls to Government officials were made in order to obtain supplementary information that was not readily available online – or proved very problematic to find.

The paper will first provide background information about Norwegian whaling, the minke whale, and its status within various organisations. The second part of the paper will discuss the relevant laws and regulations concerning whaling under Norwegian domestic law. The last part will discuss various levels of transparency. The authors observed three categories of transparency: high, medium, and low. The research was also divided into these three categories. The conclusion will provide a summary of the findings and determine the level of transparency in modern Norwegian whaling from 2006 until 2015.

Background Information Concerning Norwegian Whaling

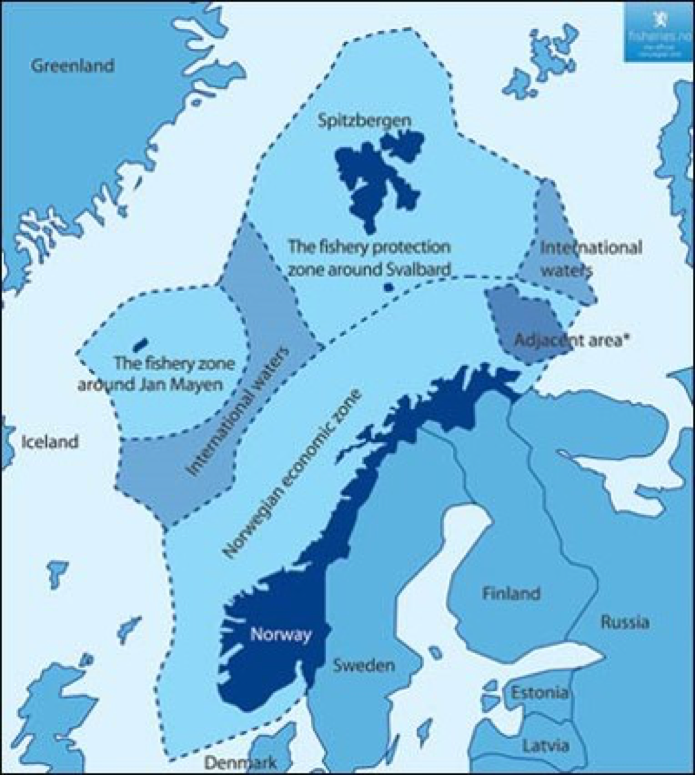

The common minke whale is a small sized baleen whale that is widely distributed in the world’s oceans, though it is most commonly found in the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic Ocean minke whale is divided into four stocks; East Canada, West Greenland, Central-North and Northeast. Norway has hunted all stocks apart from East Canada. Presently, however, Norway mainly whales in the Northeast Atlantic.[3] Norwegian whaling takes place in the Norwegian EEZ, the fisheries zone around Jan Mayen, the fisheries protection zone around Svalbard,[4] and Smutthavet – international waters between Jan Mayen and the Norwegian EEZ.[5]

(Source: www.projourno.org)

Prior to 2006, the catch area was divided into five zones: ES (Svalbard), EB (Barents Sea), CW (Jan Mayen), EW and EN (Norwegian EEZ). However, due to new regulations in 2006 the quotas were no longer subdivided between the zones. Since 2006 Norway has operated with three main areas as opposed to the five zones, as seen in the map above, but the minke whale quota is no longer divided between the areas. Whaling vessels can catch as many whales as they have the capacity to catch, in any area, as long as the overall annual quota is not exceeded.[6] The season for whaling is from April to September, the most important months being May, June and July. Moreover, whaling is only a small-scale coastal business in Norway, and less than 5 percent of the workforce in Northern Norway works in the fishing and whaling industry. However, in some of the small island communities in Northern Norway fishing and whaling employs as much as 40 percent of the population.

Between 1988 and 1992 Norway ceased its whaling activities. However, it became evident that the minke whale stocks were larger than previously believed, and Norway decided that it was possible to hunt minke whale in the Northeast and Central Atlantic in a sustainable manner.[7] Due to the IWC reservation Norway can set its own national quotas.[8] The last year a quota was fulfilled, and breached by 1%, was 2001; since 2001 the quotas have not been fulfilled.[9]

Due to findings made by Havforskningsinstituttet (Institute of Marine Research) through their DNA database, it was discovered that there are no subpopulations of minke whale in the Norwegian catch area, and consequently, the Norwegian Government saw no need to keep the five zones and divide the catch between the areas, as there were no genetic reasons to continue the practice.[10] Fiskeridirektoratet (Directorate of Fisheries), based on research done by the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) Scientific Committee and their Revised Management Procedure (RMP), sets the quota for the Norwegian catch zone.[11] The Northeast minke whale stock alone counts more than a hundred thousand whales, and the quota for 2010-2015 was 1286, approximately 1% of the stock.[12] The actual catch from 2006-2015 was lower than the designated quotas.[13]

In addition to the Norwegian research, both the North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission (NAMMCO) and the IWC conduct research concerning the abundance of minke whale stocks. NAMMCO states that minke whales are the most abundant of the baleen whales; estimated minke whale numbers from NAMMCO date back to 2007 and were set to ca. 112,000 individuals in the Northeast Atlantic; no numbers were available for the Central Atlantic area.[14] The IWC provides stock estimates which lie between 60,000 and 130,000 individuals in the Northeast Atlantic with a median of 90,000; for the Central Atlantic the median lies at 50,000 individuals, with estimates between 30,000 and 85,000.[15]

Norway is a member of the IWC, but when IWC decided on the moratorium in 1982 (enforced from the 1986 season), the Norwegian Government immediately made reservations and objections to Schedule paragraph 10(e) concerning the moratorium.[16] Due to the reservations, Norway argues that the moratorium does not concern them.[17] In addition to the minke whale being protected by the moratorium, it is also listed in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix I.[18] Norway also made reservations against listing the minke whale in Appendix I by CITES, due to the aforementioned research revealing that the common minke whale is plentiful, with the Northeast stock alone counting more than a hundred thousand individuals.[19]

Domestic Laws and Regulations Concerning Norwegian Whaling

Under Norwegian domestic law, there is one law dealing with marine resources, Havressursloven (law of resources of the sea), and it includes various regulations concerning whaling.[20] Havressursloven was established in 2008 and last amended in 2015 (2008/15). Additionally, there are two laws dealing with the conservation of species, biodiversity and wildlife; Naturmangfoldloven (law on biodiversity), which regulates sustainable use of all wild species, terrestrial and marine,[21] and Viltloven (law regulating hunting of wild animals).[22] Additionally, there are many other regulations, called j-meldinger. Currently there are 260 valid j-meldinger, all of them regulate fisheries and whaling. A few of these deal with whaling specifically. There are regulations on the use of tachograph and electronic supervision regarding catch (J-28-2015), regulations on electronic position reporting (J-215-2015), regulation on concession and quota (J-262-2015), regulation on participation (J-174-2015), and lastly J-33-2013, which is the Forskrift om utøvelse av fangst av vågehval. J-33-2013 deals solely with the regulation of minke whale whaling.[23] Many of the other j-meldinger deal with fisheries as well as whaling. All regulations, apart from J-174-2015, are pursuant to Havressursloven under various paragraphs.[24] J-174-2015 is not pursuant to Havressursloven because it deals with a separate law, Deltakerloven, regulating who can partake in fishing and whaling.[25]

Some j-meldinger are worth explaining in more detail, for example J-33-2013 Forskrift om utøvelse av fangst av vågehval (2000/13),[26] which sets out clear parameters and requirements for the equipment on whaling vessels as well as dumping of those parts of the whale that are not used for consumption in Norway.[27] This regulation is also regularly updated, albeit not as regularly as the overarching Havressursloven. J-33-2013, in the first paragraph, states that the killing must be done so as not to cause the animal unnecessary suffering.[28] However, what exactly constitutes unnecessary suffering is not explained. Another regulation describes the requirement for the use of the electronic registration system: Forskrift om bruk av ferdskriver for elektronisk overvåking av fangst av hval (2007/13).[29] When at sea, the system must send data to Fiskeridirektoratet every 24 hours. The electronic system has replaced the personal at-sea inspection almost entirely.[30]

Fiskeridirektoratet is in charge of the proper implementation of the aforementioned regulations and inspecting its adherence at sea. However, Fiskeridirektoratet has charged Kystvakten (the Norwegian Coastguard) with the inspections and issuing of reports.[31] Regarding whaling permits, Fiskeridirektoratet only provides whaling permits for one year at a time, which means that captains of the whaling vessels must apply for whaling permits anew annually. Fiskeridirektoratet also has the power to retract the whaling permit if the crew or vessel is not compliant with the regulations or fails to pass the training.[32] Despite repeated online searches and requests via e-mail and phone calls, it was difficult to find information concerning training contents and length – which will be discussed in more detail below.

For the chosen timeframe of this paper, only one court case concerning whaling was found. The case concerned a whaler who was caught using so-called non-explosive or ‘cold’ harpoons instead of the obligatory grenade harpoons. Despite the fact that the captain had noted the use of illegal harpoons in his logbook, the whaler was not discovered until after the vessel had been reported to a land-based police station by an inspector, who had become suspicious during a routine inspection and subsequently reported it.[33] Fiskeridirektoratet had not noticed the use of the cold harpoons from the electronic registration system, and apparently not read the logbooks either. The case was dismissed, however, due to technicalities with the charges.[34] The example leads to questions of the effectiveness of the rule of law and consequences for whalers who have been found in breach with the law. The laws and regulations are clear and understandable, but the implementation requires more scrutiny.

Transparency

The following section discusses various topics related to Norwegian whaling. For clarity, this section has been divided into three parts: high transparency, medium transparency, and low transparency. As mentioned in the introduction, we evaluate transparency according to the ease of accessing information and its quality.

High Transparency

Laws and Regulations and Quota Setting

The investigation concerning transparency in Norwegian whaling commenced by looking into the information provided on the official website of the Norwegian Government.[35] By doing a simple search on whaling, numerous hits directed the authors to laws, regulations, reports and information about biodiversity and sustainability in general, and whaling specifically. Information about the laws mentioned above and regulations are transparent, easily accessible, of good quality, and up to date. Information about the regulations (j-meldinger) pursuant to the laws are provided: when it was last updated, what Government body is authorised, when it was first passed, and of course, the content of the law is given. Furthermore, the Government is transparent concerning their commercial whaling. It is stated on the official websites and documents that the whaling is for commercial purposes purely, and that they whale legally in spite the IWC moratorium due to the reservations concerning the moratorium made from the onset. The Government is also transparent regarding their relationship with the IWC, and their disagreement with the moratorium.[36] Information about why, where, and which species they whale is also transparent,[37] as well as the history of whaling and what happens with the whale meat.[38] Moreover, laws and regulations on the export of minke whale products, mainly meat, is also transparent.[39] However, most of the meat is for domestic consumption.

The transparency in relation to quota setting is also transparent. The Government provides detailed information about the annual quotas and how many animals were taken. Furthermore, the Government is open about the research behind the quota setting and the collaboration with IWC’s Scientific Committee. The division of the quotas among the various areas was transparent as well,[40] although this is no longer relevant due to the aforementioned minke whale DNA research. Havforskningsinstituttet and their research is also transparent: there are numerous links and pdfs one can download, the website and the information is regularly updated, it is easily accessible and the quality of the information is good.[41]

Material about required equipment and crew on whaling vessels is transparent as well, and it is available on the webpage of Fiskeridirektoratet.[42] Links to the laws and regulations dealing with equipment, weapons, enforcement, punishment and crew of whaling vessels, are all available, easily accessible, clear and up to date. Regulation regarding training for whalers and who is entitled to the training are also available and transparent; however, the content of the trainings is less transparent.[43] This will be discussed in more detail below.

Medium Transparency

Language availability

The authors found that since they are fluent in Norwegian, more information was available to them. Thus, some of the information that is transparent, is only transparent for Norwegian speakers. The official Government websites are available in English as well as in Norwegian, but for example, links to reports to the Government from Nærings- og Fiskeridepartementet (the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries), called St.meld., are only available in Norwegian. On the website it clearly states that it is not available in English.[44] Thus, some information from Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet and Fiskerdirektoratet, to the Government about the internal affairs regarding whaling, inspections aboard the whaling vessels, and breaches of the laws, are only available in Norwegian. The websites used by the authors for the j-meldinger, are also only available in Norwegian. Information from Lovdata, which was frequently utilized in this article, for information about laws concerning whaling, regulations, training and so forth, is also in Norwegian only. Hence, for a person understanding Norwegian, more information is available and thus, the transparency level is higher in Norwegian than the information that is available in English. The information from the IWC and certain articles are published in English,[45] but the greater percentage of the articles, reports, and website information used for this paper, was read in Norwegian because it was the available language. Consequently, for in depth detail regarding Norwegian whaling, one needs to know Norwegian.

DNA Database

The minke whale DNA database merits closer inspection in terms of transparency. Information about the database (when it was initiated, what can be found, who does the registering of the material and how it works) are available online and are transparent. However, the database itself is not. After numerous attempts to access the online DNA database for minke whales through the webpages of Havforskningsinstituttet, Fiskeridirektoratet and other official websites, the authors decided to contact Havforskningsinstituttet. Tore Haug, the lead scientist, informed the authors that Havforskningsinstituttet merely does the analyses and registers the information in the database; they do not supervise the database itself.[46] Haug also informed the authors that the Government body who manages the database is Fiskeridirektoratet. Hild Ynnesdal at Fiskeridirektoratet could inform the authors that the database is not open and accessible online, but anyone can call or email[47] Fiskeridirektoratet and receive information about the whale meat they purchased, for example.[48] The authors were also informed that the purpose of the database was originally to ensure that all minke whales are caught and sold in compliance with the laws and regulations of domestic Norwegian law. However, the database turned out to yield valuable information about the minke whale stocks, for instance the information that lead to de-zoning the original five whaling zones, as mentioned previously. Though the public can access the information and nothing is confidential or hidden, it is not disclosed openly online and one has to make an extra effort to receive the information. On the one hand one can argue that the DNA database is transparent since none of the information relating to the database is confidential or inaccessible, but on the other hand, transparency, as defined for the purpose of this paper, entails ease of accessing information and disclosure of the information. Hence, the minke whale DNA database does not comply with transparency, but is rather semi-transparent as much information is available, but not all.

Training and Training Contents

Another issue that is not as transparent as it could be is the organisation of the trainings. This aspect is particularly important as the whalers, in particular the captain and the harpoonist, are required to have training on a regular basis to prove they know how to use the cannon and harpoon grenades and know how to kill the whale humanely. Despite requests by e-mail[49] and close examination Fiskeridirektoratet’s website in Norwegian, it remained unclear what constitutes the contents of the training apart from shooting practice, for example whether the shooters learn about minke whale biology and how to separate an adult whale from a youngster.[50] Neither did it become clear if Fiskeridirektoratet does indeed organise trainings every year, as claimed by the official English language website of Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet.[51] However, contacting Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet does open doors. Ms. Ynnesdal could inform the authors that the courses cover basic minke whale anatomy, where to shoot the whale, the angle, and distance. The authors learned that, apart from the basic anatomy, which is required knowledge for the shooting of whales in a manner that provides the least suffering, biology is not a part of the training, and that the whalers can shoot any minke whale they see, regardless of supposed age and size.[52] Furthermore the authors learned that whaling captains and harpoonists have to pass shooting tests annually: harpoon at sea and rifle on land. Additionally, the mandatory basic course is generally only required once, unless new regulations are set forth or new equipment is assigned.[53] There seem to be no online documents offering information about detailed contents of the training. As mentioned earlier, laws and regulations regarding training for whalers are transparent,[54] but the content of the mandatory courses, are not transparent because these do not appear to be accessible. From the above it appears that Fiskeridirektoratet is not actively hiding information about the courses and training whalers have to go through; however, the information is not easily accessible and available online.[55]

Electronic Registration System and Time to Death

The electronic registration system that whaling vessels are required to have on board merits a few questions as well. It is unclear how the system works in the fullest extent. For example, it cannot register whether the whale was shot in a way that did not cause any unnecessary suffering, a requirement by law, and how fast it died.[56] It can only register how many shots were fired. The fact that there are barely any inspections done on at-sea whaling vessels leaves room for bending the truth concerning the actual time between the shooting of the animal and when it died. The Norwegian government declares that currently ca. 80% of the animals die within the timeframe of two minutes, even though Norway continued to cite 2002 data concerning Time to Death (TTD) at IWC meetings in 2009.[57] In order to check whether the claim by the Norwegian government is correct and can be supported by research, the authors decided to contact Fiskeridirektoratet once more. After several attempts the authors received the information that the NAMMCO expert group on “Assessing TTD data from Large Whale Hunts” had published a report concerning TTD in November 2015.[58] In this report the collection of data is explained, and the TTD in all whaling nations and areas are assessed. According to this report the average TTD was reduced from 11.5 minutes in 1981 to 1 min in 2012.[59] The report also explains how TTD can be measured aboard ships, as this is not done by the electronic system mentioned earlier: ‘The electronic system does not record TTD but it records time and position of every whale shot and taken on board for flensing through various movement sensors placed in strategical places on the boat connected to a GPS. This means that data from this system may give an indication as to whether the whale died quickly or slowly.’[60] The report proceeds to discuss the results from the 2011 and 2012 seasons, in which 82% of the whales died instantaneously after being shot. The whales that did not die instantaneously had an average TTD of 6 minutes, one whale only died after 20-25 minutes according to the report.[61] The TTD claim by the Norwegian government mentioned in the beginning of this paragraph can be considered correct and the data to back the claim can be found online. Therefore, the discussion concerning the TTD can be considered transparent, although finding the NAMMCO report was not straightforward to locate online; however, this is not the responsibility of the Norwegian government. Nevertheless, for clarity reasons the government website could also refer to the NAMMCO report, this would show that the government is serious about their claims and can provide scientific evidence for them.

Low Transparency

Confidential Coast Guard Reports

During the time of research concerning transparency in Norwegian whaling, only one area was found not to be transparent as the information is unavailable online, nor is it provided when requested: the reports by Kystvakten and Fiskeridirektoratet from the onboard controls or when landing the catch. After having found information about regulation and enforcement of whaling, mandatory electronic equipment to register catch, and the compliance of whaling vessels with the laws and regulations,[62] no information could be found about the reports. Therefore, the authors called Fiskeridirektoratet once again.[63] From information about controls in the fiske og fangst (fishing and catch) industry, it was the authors’ impression that Kystvakten performed the controls. On Kystvakten’s website, it clearly states that the reports are confidential.[64] However, no reasons for the confidentiality were given.

Nonetheless, the conversation with Janne Andersen at Fiskeridirektoratet Nordland[65] informed the authors that first of all, it is Kystvakten’s regulation that all information of such nature as reports are confidential, because they are part of the Norwegian Navy. Second, Kystvakten very rarely performs control on whaling vessels, as their focus is on controlling fisheries. Fiskeridirektoratet themselves regulates and carries out the controls of whaling vessels through the equipment that is required on board, such as the tachograph, black/blue box and diary of the catch. Occasionally there is an observer from Fiskeridirektoratet aboard the vessels, more often there are controls when the vessels land the whales. Ms. Andersen also informed the authors that the reports are confidential because a report is only made when someone is not in compliance with the laws and regulations. The reason the reports are confidential is because someone is reported to the authorities. Hence, they are confidential on the same grounds that police reports are confidential when someone is reported to the police for breaking the law. In the same manner the public cannot access police reports, the reports from the controls, and thus the breaching of the law, are confidential as well.

Because the reports are confidential, it also seems that information about what yields reporting to Fiskeridirektoratet and/or the police is confidential. The overall idea that being in breach of the regulations and laws will lead to certain consequences is obvious enough, but beyond that it seems that no information is obtainable. Breaking the laws and regulations will have consequences, but what breach will lead to what consequence is not available, at least as far as the authors were able to acquire.

Conclusion

The common minke whale whaling as conducted by Norway, takes place under the reservations made by the Norwegian government concerning the IWC moratorium. According to the IWC and NAMMCO, the common minke whale is the most abundant of the baleen whales and the stock is thought to exceed 100,000 individuals in the North Atlantic. The annual Norwegian whaling quota does not exceed 1-2% of the total minke whale stock, and quotas are rarely fulfilled. The quota setting has a high level of transparency and the research showed that the Norwegian government collaborates with IWC and NAMMCO in order to determine the quotas and are set based on the scientific evidence provided by the organisations mentioned above. Furthermore, the numbers of the caught animals are also readily available online.

Many laws and regulations regulate the whaling activities, one of the most important ones being the J-33-2013 Forskrift om utøvelse av fangst av vågehval (2000/13). These laws and regulations are regularly updated and can easily be found online. Therefore, the laws and regulations as such can be considered transparent as they are easily accessible and understandable. However, as the reports of the Kystvakten are confidential, and the only court case that could be found was dismissed due to technicalities, it cannot be established how effective the rule of law is. The true effectiveness of the rule of law therefore deserves more scrutiny in the opinion of the authors, because rule of law without effectiveness undermines itself.

Several points are at a medium level of transparency. The information concerning training and training contents, as well as the electronic data system and the TTD could be made more accessible. The TTD data required extensive calling with the Fiskeridirektoratet and the research concerning TTD in particular yielded conflicting information in the beginning. It was not until several phone calls were made that the authors were provided with the location of the most recent NAMMCO TTD document. However, once this document was found the questions concerning TTD were answered quickly and satisfactorily. The only non-transparent finding was the reporting system from the Kystvakten, as these were considered to be non-public in the same manner as police reports.

It must be noted that, when asking the Government bodies for more detailed information, it was more readily provided when requested in Norwegian rather than English, and phone calls in Norwegian were most effective during the investigation for this paper. Considering Ms Tiili is a Norwegian native speaker and Ms Ramakers speaks Norwegian at an advanced level, information is easily accessible. However, when Ms Ramakers requested information in English, emails were not answered. Some English language websites are available for non-Norwegian speakers; however, most information by the Norwegian Government was only available in Norwegian. Nevertheless, this enquiry revealed that, in general, the Norwegian Government has a medium to high level of transparency concerning their modern, commercial whaling (2006-2015). This can be concluded since a lot of information is easily accessible, the quality of the information is good, the information is updated and, from what this research could deduce, it does not appear that the Norwegian Government is hiding information regarding their commercial whaling activities.

Bibliography

Cites and Cites, ‘CITES Appendices I, II, and III’ (2008) 4 Journal of minimal access surgery 85

Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘St.meld. Nr. 46 (2008–2009) Norsk Sjøpattedyrpolitikk’, vol 46 (2009)

Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’ (2013) 40

Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Norsk vågehvalfangst’ (18 December 2013) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumentarkiv/Regjeringen-Bondevik-II/fkd/Tema-og-redaksjonelt-innhold/Redaksjonelle-artikler/2005/om-norsk-hvalfangst/id437319/> accessed 25 February 2016

Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Fiskeridirektoratet – Høring Om Forslag Til Forskrift Om Deltakelse I Og Regulering Av Fangst Av Vågehval I 2012’ (2012) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Dokumenter/Hoeringer/Hoering-om-forslag-til-forskrift-om-deltakelse-i-og-regulering-av-fangst-av-vaagehval-i-2012> accessed 26 February 2016

Fiskerdirektoratet, ‘Posisjonsrapportering’ (2014) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Rapportering/Fartoey-over-15-meter-med-flere/Posisjonsrapportering> accessed 26 February 2016

Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Fiskeridirektoratet’ (2016) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/> accessed 26 February 2016

Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Fiskeridirektoratet J-215-2015’ (2016) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger/Gjeldende-J-meldinger/J-215-2015> accessed 26 February 2016

Fiskerdirektotatet, ‘J-Meldinger’ (2016) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger?filter=yes&status%255B%255D=Gjeldende&search=hval> accessed 25 February 2016

Fiskeries, ‘Norwegian Whaling – Based on a Balanced Ecosystem’ (2016) <http://www.fisheries.no/ecosystems-and-stocks/marine_stocks/mammals/whales/whaling/> accessed 25 February 2016

Forsvaret, ‘Kystvakta – Forsvaret.no’ <https://forsvaret.no/fakta/organisasjon/Sjoeforsvaret/Kystvakten> accessed 16 February 2016

Havforskningsinstituttet, ‘Havforskningsinstituttet – Unødvendig Med Fem Fangstområder for Vågehval’ (2016) <http://www.imr.no/publikasjoner/andre_publikasjoner/kronikker/2014_1/unodvendig_med_fem_fangstomrader_for_vagehval/nb-no> accessed 25 February 2016

Hjort J, ‘Lover Og Regler – En Historisk Gjennomgang’

International Whaling Commission, ‘An Overview of the Elements/issues Identified as Being of Importance to One or More Contracting Governments in Relation to the Future of the IWC’

IWC, ‘The IWC – Revised Management Procedure (RMP)’ (2016) <https://iwc.int/rmp2> accessed 25 February 2016

Lovdata, ‘Lov Om Forvaltning Av Viltlevande Marine Ressursar (Havressurslova) – Lovdata’ (2008) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2008-06-06-37> accessed 16 February 2016

Lovdata, ‘Forskrift Om Utøvelse Av Fangst Av Vågehval – Lovdata’ (2013) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2000-03-31-312?q=forskrift om ut%25C3%25B8velse av fangst> accessed 25 February 2016

Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘J-174-2015: Deltakerloven’ (2015) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger/Gjeldende-J-meldinger/J-174-2015> accessed 25 February 2016

Lovdata, ‘Lov Om Jakt Og Fangst Av Vilt (Viltloven) – Lovdata’ (2015) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1981-05-29-38#KAPITTEL_6> accessed 25 February 2016

Miljøvernrepartement DK, ‘Oppdatering Av Forvaltningsplanen for Det Marine Miljø I Barentshavet Og Havområdene Utenfor Lofoten’ (2011) 10 Melding til Stortinget 1

Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’ (regjeringen.no, 2013) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-40-20122013/id729136/> accessed 1 December 2016

Regjeringen, ‘Kvalfangst’ (5 March 2015) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/mat-fiske-og-landbruk/fiske-og-havbruk/hval-og-sel-listeside/kvalfangst/id2001553/> accessed 16 February 2016

Ómar Ágústsson H and Lorna Johnstone R, ‘Practising What They Preach: Did the IMF and Iceland Exercise Good Governance in Their Relations 2008-2011?’ (2013) 8 Nordicum-Mediterraneum 1

regjeringen.no, ‘regjeringen.no’ (5 January 2015) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/id4/> accessed 26 February 2016

Statens forvaltningstjeneste, ‘Lov Om Bevaring Av Natur, Landskap Og Biologisk Mangfold (Naturmangfoldloven)’ (2004)

Utenriksdepartementet, ‘Eksport av norske vågehvalprodukter’ (4 October 2006) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/eksport-av-norske-vagehvalprodukter/id87866/> accessed 26 February 2016

Øien N, ‘Økosystemet Barentshavet’, Havets ressurser og miljø (2006)

Endnotes

[1] Fiskeries, ‘Norwegian Whaling – Based on a Balanced Ecosystem’ (2016) <http://www.fisheries.no/ecosystems-and-stocks/marine_stocks/mammals/whales/whaling/> accessed 25 February 2016.

[2] Hjálti Ómar Ágústsson and Rachael Lorna Johnstone, ‘Practising What They Preach: Did the IMF and Iceland Exercise Good Governance in Their Relations 2008-2011?’ (2013) 8 Nordicum-Mediterraneum 4.

[3] Nils Øien, ‘Økosystemet Barentshavet’, Havets ressurser og miljø (2006); Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet, ‘Kvalfangst’ (5 March 2015) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/tema/mat-fiske-og-landbruk/fiske-og-havbruk/hval-og-sel-listeside/kvalfangst/id2001553/> accessed 16 February 2016.

[4] 87 percent of the territorial sea around Svalbard protected, and whaling is not permitted in those areas. See Det Kongelige Miljøvernrepartement, ‘Oppdatering Av Forvaltningsplanen for Det Marine Miljø I Barentshavet Og Havområdene Utenfor Lofoten’ (2011) 10 Melding til Stortinget 1 for more information.

[5] Øien; Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’ (2013) 40 41.

[6] Hild Ynnesdal at Fiskeridirektoratet informed the authors about this during our phone conversation on February 24th 2016.

[7] Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, ‘Norwegian Whaling – Based on a Balanced Ecosystem’ (2013) fisheries.no <http://www.fisheries.no/ecosystems-and-stocks/marine_stocks/mammals/whales/whaling/> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[8] International Whaling Commission, ‘Catch Limits & Catches Taken’ (2016) < https://iwc.int/catches#comm> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[9] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘HØRINGSNOTAT – Forslag Til Forskrift Om Deltakelse I Og

Regulering Av Fangst Av Vågehval I 2012’ (2012) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/fiskeridir/Media/Files/yrkesfiske/dokumenter/hoeringer/2012/hoeringsnotat-vagehval-2012> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[10] ibid; Havforskningsinstituttet, ‘Havforskningsinstituttet – Unødvendig Med Fem Fangstområder for Vågehval’ (2016) <http://www.imr.no/publikasjoner/andre_publikasjoner/kronikker/2014_1/unodvendig_med_fem_fangstomrader_for_vagehval/nb-no> accessed 25 February 2016.

[11] Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘St.meld. Nr. 46 (2008–2009) Norsk Sjøpattedyrpolitikk’, vol 46 (2009) 7; International Whaling Commission, ‘An Overview of the Elements/issues Identified as Being of Importance to One or More Contracting Governments in Relation to the Future of the IWC; for more information about RMP, see International Whaling Commission, ‘The IWC – Revised Management Procedure (RMP)’ (2016) <https://iwc.int/rmp2> accessed 25 February 2016.

[12] Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet, ’Kvote for vågehval i 2016’ <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/aktuelt/kvote-for-vagehval-i-2016/id2480554/> accessed 10 August 2016.

[13] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘HØRINGSNOTAT – Forslag Til Forskrift Om Deltakelse I Og Regulering Av Fangst Av Vågehval I 2012’ (2012).

[14]The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, ‘Minke Whale Stock Status’ (2016) <http://www.nammco.no/marine-mammals/whales-and-dolphins-cetaceans/new-common-minke-whale/stock-status/> Accessed 6 March 2016; The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, ‘Common Minke Whale’ (2016) <http://www.nammco.no/marine-mammals/whales-and-dolphins-cetaceans/new-common-minke-whale/> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[15] International Whaling Commission, ‘Whale Population Estimates’ (2016) <https://iwc.int/estimate> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[16] Johan Hjort, ‘Lover Og Regler – En Historisk Gjennomgang’ 2; International Whaling Commission, ‘An Overview of the Elements/issues Identified as Being of Importance to One or More Contracting Governments in Relation to the Future of the IWC’ 12.

[17] Øien 41; Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Norsk vågehvalfangst’ (18 December 2013) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumentarkiv/Regjeringen-Bondevik-II/fkd/Tema-og-redaksjonelt-innhold/Redaksjonelle-artikler/2005/om-norsk-hvalfangst/id437319/> accessed 25 February 2016.

[18] Cites and Cites, ‘CITES Appendices I, II, and III’ (2008) 4 Journal of minimal access surgery 85.

[19] Miljøvernrepartement; Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘St.meld. Nr. 46 (2008–2009) Norsk Sjøpattedyrpolitikk’.

[20] Lovdata, ‘Lov Om Forvaltning Av Viltlevande Marine Ressursar (Havressurslova) – Lovdata’ (2008) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2008-06-06-37> accessed 16 February 2016.

[21] Statens forvaltningstjeneste, ‘Lov Om Bevaring Av Natur, Landskap Og Biologisk Mangfold (Naturmangfoldloven)’ (2004).

[22]Lovdata, ‘Lov Om Jakt Og Fangst Av Vilt (Viltloven) – Lovdata’ (2015) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1981-05-29-38#KAPITTEL_6> accessed 25 February 2016.

[23] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘J-Meldinger’ (2016) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger?filter=yes&status%255B%255D=Gjeldende&search=hval> accessed 25 February 2016; Lovdata, ‘Forskrift Om Utøvelse Av Fangst Av Vågehval – Lovdata’ (2013) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2000-03-31-312?q=forskrift om ut%25C3%25B8velse av fangst> accessed 25 February 2016.

[24] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘J-Meldinger’.

[25] Lovdata, ‘J-174-2015: Deltakerloven’ (2015) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger/Gjeldende-J-meldinger/J-174-2015> accessed 25 February 2016.

[26] Forskrift om utøvelse av fangst av vågehval (2000/13) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2000-03-31-312> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[27] Ibid. §7.

[28] Ibid. §1.

[29] Forskrift om bruk av ferdskriver for elektronisk overvåking av fangst av hval (2007/13) <https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2007-03-14-297?q=hval> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[30] Economics for the Environment Consultancy Ltd. (eftec), ‘Norwegian Use of Whales: Past, Present and Future Trends, Final Report’ (2011) NOAH, WSPA, Dyrebeskyttelsen Norge <http://www.dyrebeskyttelsen.no/nyheter/nordmenn-vil-ikke-lenger-ha-hvalkjott> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[31] The Norwegian Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, ‘Exercising Resource Control’ (2016) <http://www.fisheries.no/resource_management/control_monitoring_surveillance/Exercising_resource_control/> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[32] Fiskeridirektoratet – Høring Om Forslag Til Forskrift Om Deltakelse I Og Regulering Av Fangst Av Vågehval I 2012’ <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Dokumenter/Hoeringer/Hoering-om-forslag-til-forskrift-om-deltakelse-i-og-regulering-av-fangst-av-vaagehval-i-2012> accessed 26 February 2016.

[33] Economics for the Environment Consultancy Ltd. (eftec), ‘Norwegian Use of Whales: Past, Present and Future Trends, Final Report’ (2011) NOAH, WSPA, Dyrebeskyttelsen Norge, 17.

[34] Economics for the Environment Consultancy Ltd. (eftec), ‘Norwegian Use of Whales: Past, Present and Future Trends, Final Report’ (2011) NOAH, WSPA, Dyrebeskyttelsen Norge, 18.

[35] regjeringen.no, ‘regjeringen.no’ (5 January 2015) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/id4/> accessed 26 February 2016.

[36] Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘St.meld. Nr. 46 (2008–2009) Norsk Sjøpattedyrpolitikk’; Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’.

[37]regjeringen.no.

[38] Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘St.meld. Nr. 46 (2008–2009) Norsk Sjøpattedyrpolitikk’; Det Kongelige Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’.

[39] Utenriksdepartementet, ‘Eksport av norske vågehvalprodukter’ (4 October 2006) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/eksport-av-norske-vagehvalprodukter/id87866/> accessed 26.

[40] All numbers of the quotas were and am available and also how the quota numbers are reached.

[41] Havforskningsinstituttet.

[42] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Fiskeridirektoratet’ (2016) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/> accessed 26 February 2016.

[43] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Posisjonsrapportering’ (2014) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Rapportering/Fartoey-over-15-meter-med-flere/Posisjonsrapportering> accessed 26 February 2016.

[44] Nærings- og fiskeridepartementet, ‘Meld. St. 40 (2012–2013)’ (regjeringen.no, 2013) <https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld-st-40-20122013/id729136/> accessed 1 December 2016.

[45] Information about the minke whale database, for instance, was found in an article written in English.

[46] Phone call made on February 26th 2016.

[48] Phone call made on February 26th 2016.

[49] The request by e-mail to the general e-mail address and was made in English, the Directorate has not responded.

[50] This may be important due to the relative long time that it takes before a minke whale to reach adulthood (7-8 years according to the American Cetacean Society). American Cetacean Society, ‘Minke Whale’ <http://acsonline.org/fact-sheets/minke-whale/> Accessed 6 March 2016.

[51] Fiskeridirektoratet, <http://www.fisheries.no/ecosystems-and stocks/marine_stocks/mammals/whales/whaling/> accessed 6 March 2016.

[52] H. Ynnesdal of the Directorate of Fisheries in Bergen in a phone call with Kristin Tiili.

[53] Information that is available on and through Fiskeridirektoratet’s webpage.

[54] See J-47-2014, J-33-2015, J-28-2013, J-33-2013 at www.fiskeridir.no for more detailed information about the regulations.

[55] Fiskeridirektoratet, ‘Fiskeridirektoratet – Høring Om Forslag Til Forskrift Om Deltakelse I Og Regulering Av Fangst Av Vågehval I 2012’ (2012) <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Dokumenter/Hoeringer/Hoering-om-forslag-til-forskrift-om-deltakelse-i-og-regulering-av-fangst-av-vaagehval-i-2012> accessed 26 February 2016.

[56] Economics for the Environment Consultancy Ltd. (eftec), ‘Norwegian Use of Whales: Past, Present and Future Trends, Final Report’ (2011) NOAH, WSPA, Dyrebeskyttelsen Norge, 17.

[57] Fiskeri- og Kystdepartementet, ‘Norsk vågehvalfangst’ (2013) Regjeringen Bondevik II.< https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumentarkiv/Regjeringen-Bondevik-II/fkd/Tema-og-redaksjonelt-innhold/Redaksjonelle-artikler/2005/om-norsk-hvalfangst/id437319/> Accessed 6 March 2016; Eftec (n18) 17.

[58] NAMMCO, Expert Group Meeting on Assessing TTD Data from Large Whale Hunts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 4-5 November 2015.

[59] ibid. 6.

[60] ibid.

[61] ibid.

[62] Particularly J-215-2015 §12, see ‘Fiskeridirektoratet J-215-2015’ <http://www.fiskeridir.no/Yrkesfiske/Regelverk-og-reguleringer/J-meldinger/Gjeldende-J-meldinger/J-215-2015> accessed 26 February 2016 for detailed information.

[63] Phone call made on February 24th.

[64] Forsvaret, ‘Kystvakta – Forsvaret.no’ <https://forsvaret.no/fakta/organisasjon/Sjoeforsvaret/Kystvakten> accessed 16 February 2016.

[65] Fiskeridirektoratet has divided Norway into sections, and Nordland is one of the sections.