Introduction

The composition of the Icelandic population has undergone a considerable transformation in a relatively short period of time. A medley of different cultural influences brought about by an increased number of immigrants has coloured the traditionally monolithic and culturally homogeneous Icelandic society. In early January 2025, immigrants constituted some 18,9 per cent of the total population, and their number had been rising considerably over the previous two decades, their number being some 7,4 per cent of the total population in 2012. The largest number of immigrants reside in the capital area in Iceland and represent 67,7 per cent of all immigrants. However, the proportion of immigrants among the population in different regions of the country is considerable, about 33 per cent in the South -West peninsula (Suðurnes) and some 24,5 per cent in the Westfjords (Vestfirðir) (Statistics Iceland, 2025). In this paper, we aim to establish how these massive demographic changes impact the civic culture in Iceland. We assess, with the help of specifically designed indices constructed based on empirical data, the extent to which immigrants in Iceland have become part of the civic culture upon which the Icelandic democratic society rests. As far as we know, this is the first time empirical – numerical criteria have been applied to the civic engagement of immigrants in Iceland.

The definition of immigrants follows the one used by Statistics Iceland and defines an immigrant as a person who was born abroad and has both parents and grandparents born abroad (Statistics Iceland, 2018). Immigrants in Iceland come from all over the world, although the largest single group comes from Poland (Statistics Iceland, 2025). Thus, they bring with them a variety of new ideas and cultural traditions, some of which are highly visible such as restaurants and culinary cultures, while other ideas might be more hidden such as their attitudes towards the role of government or civic engagement.

- Politics and civic culture in Iceland

Political divisions in Iceland have traditionally revolved around socio-economic issues and cultural or religious cleavages have been notably absent. For an extended period of time, the Evangelical Lutheran National Church has been relatively uncontested and religious doctrines or divisions have never constituted a real political division. Other religious congregations have been more or less absent, and the value system of a tolerant Scandinavian national church tradition has dominated society. Typically, though, as the Church has lost ground among segments of the public in the past few decades this values system has gradually taken on a more secularized nature.

Historically, the present party system dates back to the period from 1916-1930 when the four main types of parties were formed in Iceland. These parties all have ideological counterparts in the European political spectrum. They consist of a Conservative Party (Independence Party), a Centre party (Progressive Party), a Social Democratic Party (Alliance) and a Left Socialist Party (Left Green Movement). The four party types have maintained a strong position, receiving for extended periods of time more than 90 percent of the votes cast. Until 1967 their share was more that 95 percent but after a temporary drop in 1971 the four-party share fell below the 90 percent limit in the 1980s and 1990s. After the restructuring of the left in 1999, the four-party system as a whole has received some 80-85 percent of the votes. Simultaneously, since the 1980s electoral volatility has been increasing and some 1/3 of the electorate has changed parties between elections since the 1990s (Harðarson, 2008; Harðarson & Helgason, 2024). There was, however, a dramatic change after the financial collapse in 2008. In the elections of 2009, the four-parties jointly received some 90 percent of the votes but in 2013 this number was down to 74.9 percent, and in the 2016 and 2017 elections the number had fallen to the lower 60 percent (Statistics Iceland, n.d.). The economic meltdown in the autumn of 2008 dramatically affected political trust, and in particular, trust in politicians. General social trust and faith in institutional structures, which has traditionally been fairly high, remained more intact. Political trust collapsed with the economy but did not recover at the same rate as the economy, and it is only now, in the early 2020s, that political trust is reaching similar levels as before the crash (Vilhelmsdóttir & Kristinsson, 2018; Gallup 2021). A certain level of turmoil has characterised the political landscape since the 2013 parliamentary elections with a fragmentation of the party system and weak and unstable government coalitions (Vilhelmsdóttir & Kristinsson, 2018; Guðmundsson 2021; Harðarson & Helgason, 2024). This fragmentation and political volatility are, however, only partly a reflection of new cleavages and divisions in society. Rather, old divisions and factions that had been somewhat internally concealed within the four parties have surfaced and developed into new alliances, not least because of a completely changed political communication system born out of the advent of digital media and communication platforms (Guðmundsson, 2021). Although issues of a moral and culturally liberal nature have become somewhat more visible in the public discussion, it can be suggested that political divisions in Iceland by and large still unfold along a socio-economic dimension as has been the case throughout the 20th century and these are marked by the relatively homogeneous composition of the people with respect to race, culture and religion (Harðarson, 2008; Þórisdóttir, 2012). However, having said that, this traditional left-right division has been complicated by a secondary intersecting cleavage of a semi-nationalist or patriotic vs. international cooperation dimension. This dimension should be considered in light of the relatively recent establishment of Iceland as an independent republic in 1944, towards the end of the Second World War. A focus on nationality and patriotic values can be seen to have triggered an important cleavage in the latter part of the 20th century, particularly after Iceland joined NATO in 1949 and a defence agreement was concluded with the US in 1951, establishing a permanent US military base in Keflavík. Indeed, there was a wide consensus on certain patriotic values, symbolized by the Icelandic poet Snorri Hjartarson, who spoke of the true and only trinity of “land, nation and language” that had been passed on from generation to generation (Hjartarson, 1952). The question was how this trinity of values would best be preserved and whether and how a continuous presence of a foreign military was a threat to them. Towards the end of the 20th century, however, this cleavage had shifted somewhat backstage and faded away in the early 21st century when the US withdrew its base due to changed international strategic circumstances. Parallel to the NATO/US base dimension in Icelandic politics, particularly from the 1960s onward, divisions unfolded regarding the extent and depth of Icelandic participation in European integration processes (Einarsson, 2009); first towards the membership of EFTA, which Iceland joined in 1971; then towards the EEA which Iceland joined in 1994 and, eventually, towards a membership application submitted to the EU in 2009, which is still in 2026 a debated issue. The present coalition government of Kristrún Frostadóttir has on its policy programme to call a national referendum by 2027 on whether to renew the application (Evrópuvaktin, 2015, Platform, 2024). The Icelandic National Election Study at the University of Iceland (ICENES) team has further developed this second cross-cutting cleavage based og voter and candidate surveys and defined it as a ”cultural cleavage”. On the one hand there is international liberalism and on the other patriotic conservativism. This continuum involves positions on as diverse issues as liberalising drug use, gender equality, environmentalism, heavy industry, immigration, and European cooperation (Helgason and Þórisdóttir, 2024).

Thus, through the decades two salient cleavages have shaped the political environment and culture in Iceland. On the one hand, the socio-economic dimension along the left – right continuum, and, on the other, a dimension of liberal international cooperation versus a more nationalistic, patriotic “sovereignty – protective” standpoint.

This reality is reflected in the civic culture in Iceland, a culture fundamentally characterized by shared values synthesising the divisions of class and social position and the different outlooks on Iceland’s international relations. This civic culture is, therefore – as Almond and Verba (1963/89) pointed out in their seminal work– in a central role when examining the type of democratic society based upon it. Inevitably, different political cultures are to a lesser or greater extent at play at the same time within any given society and interact and negotiate with one another.

A rich body of scholarly literature on various aspects of civic culture, civic engagement, politics, and integration has been published in recent years (Chang et al. 2023). These studies often differ in nature, with some being empirical and others more conceptual in approach. Quite often they deal both geographically and subject-wise with confined areas of civic culture, such as e.g. discrimination and civic engagement (Müssig and Okrug, 2024), Vaccination hesitancy in Iceland (Meckl et al., 2025) and Eastern European youth in Britain and their political engagement (Sime and Behrens, 2023). This variety reflects the lack of consensus on the definition of the term civic culture or civic engagement, and that the concept spans various activities aimed at improving community life (Adler and Goggin, 2005; Doolittle and Faul, 2013).

The long-standing influence of Almond and Verba on scholarly discussion – and the main reason for revisiting them here – is in fact their notion of how this interaction and mediation of different cultures shapes and influences the development and form of democratic systems. This contribution is not necessarily dependent on whether one accepts the conception of three ideal-typical democratic cultures: parochial, subject or participatory cultures which Almond and Verba suggested. It is the mediation and integration of the Civic Culture that is of most importance. A slightly different but related perspective can be found in Putnam’s analysis of social capital (Putnam, 1993,2000). Unlike some other scholars such as Bourdieu, who saw social capital as a property of the individual rather than the collective, Putnam considers the social capital of large groups or societies which thus becomes a positive social and democratic quality. This then refers to social trust, trust in institutions, values and communication as important elements of social capital and the civic culture. For Putnam, trust and civic engagement therefore play a key role when it comes to democratic participation and inclusion, while other scholars acknowledge that there is a relation between the two but are not prepared to state as categorically how direct this relationship is (Portes, 1998; Fukuyama, 2001).

The civic culture or social capital in a Putnamian sense is an important element in analysing and defining different traits of democratic societies. As stated above, the Icelandic civic culture has mostly been rather homogeneous while at the same time managing to resolve and mediate between the two main political cleavages. In light of the rapid increase in the number of immigrants, people that by and large come from countries with very different political systems and civic cultures, it is far from self-evident that they would fit in and be active participants in the Icelandic civic culture and become members of an inclusive democratic society. Thus, as stated at the onset, the object of the paper is to examine how immigrants are included in the civic culture in Iceland, and to what extent this culture has mediated and absorbed new ideas and values.

- Participation, trust and acculturation of immigrants

The use of immigrants of the host country´s media is an important indicator of their participation an involvement in society. Several studies show that media use of immigrants is of major importance for their acculturation in their host countries (Dalisay, 2012; Timmermans, 2018; Jamal et al., 2019). Empirical studies of immigrants and media in America and in Europe suggest that both traditional and social media play a considerable role in the process of acculturation in a variety of ways. Clearly, the mindsets or strategies of immigrants seem to matter in the approach to media use and acculturation. Alencar and Deuze (2017) found that the media use of both host country and international media by immigrants in Spain and the Netherlands was linked to the immigrants’ strategy to integrate and to assimilate the culture, politics and language of the host society. Furthermore, they suggested that education and language skills influenced how they used news for the purpose of assimilating and/or integrating into the host society (Alencar & Deuze, 2017).

Similarly, Seo and Moon (2013) highlighted the importance of immigrants’ motives and strategies when they discovered that acculturative stress among Korean immigrants in the US encouraged a certain media use pattern. The immigrants who felt stressed tended to use ethnic news media more and US media less than those that were not stressed, and this type of news consumption pattern made them less likely to engage in civic activities related to mainstream US society (Seo & Moon, 2013).

In a study in Iceland published in 2018, Einarsdóttir et al. found that participants with a foreign background felt less connected and less cared for by the Icelandic government, and they sensed that they were less knowledgeable and less informed than participants with an Icelandic background. A very similar result was reported in the investigative journalism programme, Kveikur, shown on the national public broadcast station RÚV in September 2023 (Sigurðardóttir and Þórisson 2024).

Immigrant voter turnout has been studied and/or registered in western countries for the past few decades. In Iceland voter turnout in local elections has varied somewhat in the last two decades. One study found that voter turnout among immigrants in the 2006 local elections was about 25 per cent (Jónsdóttir, Harðardóttir & Garðarsdóttir, 2009). However, a rapid increase in numbers of immigrants in following years seemed to have lowered the turnout ratio, possibly because newly or relatively newly arrived people are less likely to vote than people that have stayed longer. This decline in turnout seems to have happened despite a change in the regulations on who has the right to vote before the 2022 elections, when the required time of residency for voting was lowered from 5 to 3 years (Hagstofa Íslands, 2025).

A study of local government elections in Sweden 2014 showed a 35 percent voter turnout among immigrants, similar to the elections in 1998-2010 (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2015). In the parliamentary elections in 2018 and 2022 the turnout among foreign citizens was between 30 and 40 percent (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2023). Kleven et al. (2022) show statistics on 50-55 percent voter turnout among immigrants in Norwegian elections in the years 2001 – 2021 (Kleven et al. 2022). Consequently, we can say that in at least three Nordic countries the voter turnout for immigrants has been 30 – over 50 percent for several decades.

As stated above social trust is instrumental in accessing social capital or the nature of the civic culture. Most often trust is divided into social trust on the one hand, which refers to trust between people in society and general legitimacy. On the other hand, institutional or political trust refers more to performance (Bjarnason, 2014). This entails that trust is conceptualised in at least two different ways. One conception sees trust as a rational evaluation or assessment of a particular condition. In this approach the focus is primarily on the trustee, the performance of the institution or actor that is to be trusted. The other conception sees trust as an affective feeling, a commitment or norm of someone that trusts. In this sense the focus is not necessarily on the trustee but on the one who trusts (Vilhelmsdóttir & Kristinsson, 2018). This can have implications for social research, and it is in this latter sense – the affective approach – that the trust discussion in relation to social capital (Putnam, 1993, 2000) and the civic culture (Almond and Verba, 1989) is based. Trust is thus seen as a stabilising democratic social and political element that is carried between generations through socialisation (Almond & Verba, 1989). Social trust and institutional trust are interlinked, and it might be suggested that social trust is an important prerequisite for institutional trust. However, Bjarnason (2014), following Rothstein and Stolle (2008), has pointed out that institutional trust can also be seen to be a prerequisite for social trust, as without institutional trust social interaction is made difficult, limiting the possibility of social trust. Whether evaluation of practice, affective predispositions or a combination of both is seen to be most important for the study of trust has not become a problem when it comes to measuring trust. Trust can be measured simply by using questionnaires that demonstrate people’s confidence in actors and institutions. Such measurements have been quite frequently used, both internationally and in Iceland. Generally, social trust has been measured high in Iceland as in the other Scandinavian countries, even to the extent that it has been seen to be a determining characteristic for this area, or “Nordic Gold” (Anderson, 2017). However, institutional or political trust in Iceland fell dramatically after the economic meltdown in 2008 (Bjarnason, 2014) whereas social trust remained intact, and it has been suggested that the loss of political trust after the economic meltdown focused more on the representational than the implementational aspect of the political system, involving a specific mistrust of actors and parties rather than signifying a legitimacy crisis (Vilhelmsdóttir & Kristinsson, 2018).

- Methodology and index construction

The aim of this study is to measure, through survey-based indices, to what extent immigrants in Iceland are acculturated to the domestic civic culture. As far as we know this is one of very few research initiatives and the most comprehensive quantitative study on immigrants’ participation and integration in Icelandic society. The analysis is based on survey material from the research project Samfélög án aðgreiningar? Aðlögun innflytjenda á Íslandi. (e. Inclusive societies? The integration of immigrants in Iceland). An electronic survey among immigrants was implemented in the fall of 2018, translated into 7 languages and containing 39 questions. Respondents were identified through the snowball sampling method where centres of continuing education language schools all around the country were the key actors in finding participants. The total number of respondents was 2,211 (Meckl & Gunnþórsdóttir, 2020:8f). Reaching immigrants in Iceland randomly is difficult due to registration matters. As the sampling method was not random rigorous statistical analysis are not possible, but we seek to give extensive descriptive statistical data. Reservations are appropriate regarding the generalisability of our results for the same reasons.

Equilateral to the immigrant survey in the fall 2018 there was also conducted a survey among Icelanders on their attitudes to inclusion of immigrants into the Icelandic society. This was done in twelve municipalities and areas which met the conditions regarding the number of immigrants residing in the areas (Sölvason and Meckl, 2019).

As stated in the introductory chapter much of scholarly literature on civic culture and civic engagement focuses on specific aspects of the phenomena, e.g. political engagement or certain social variables. However, by combining different but related variables and operationalising them in the form of indices, it is possible to obtain a better and broader picture and, ideally, gain insight into how and wether different parts of the civic culture interact and are being negotiated.

The principal index we use in most of our analyses in this article (Participatory Index) is constructed of three components, “Activity”, “Use of Icelandic media” and “Voted in the local government elections 2018”. Participation can be measured in a number of ways e.g. through membership in organisations of different types. Taking part in society is also accomplished through following domestic media (as mentioned above). Following the news and media is a form of engagement in society and hence participation. Finally, using one’s right to vote is a form of taking part in a community/society.

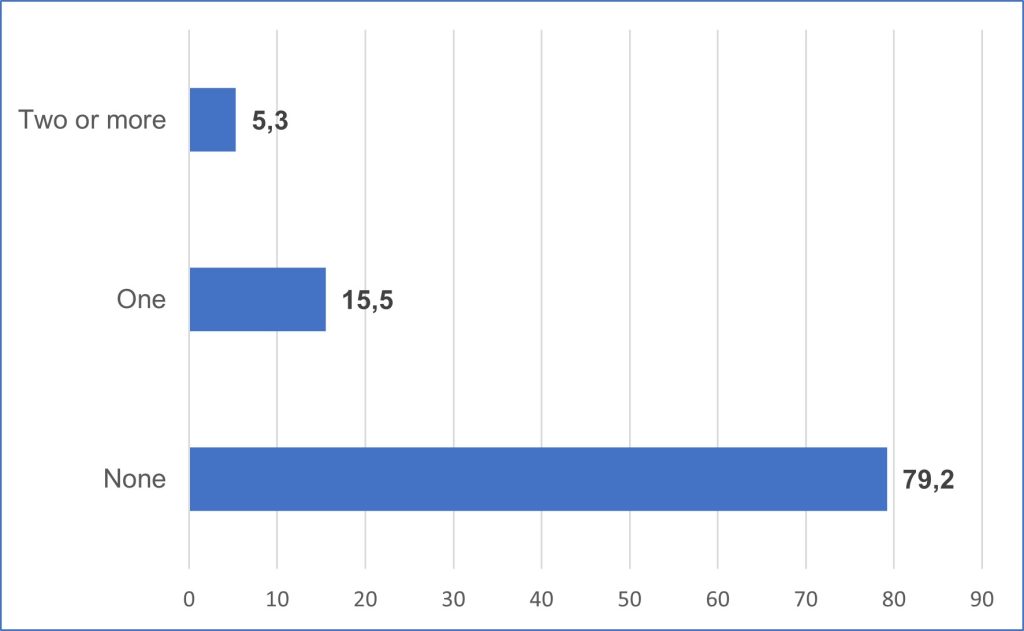

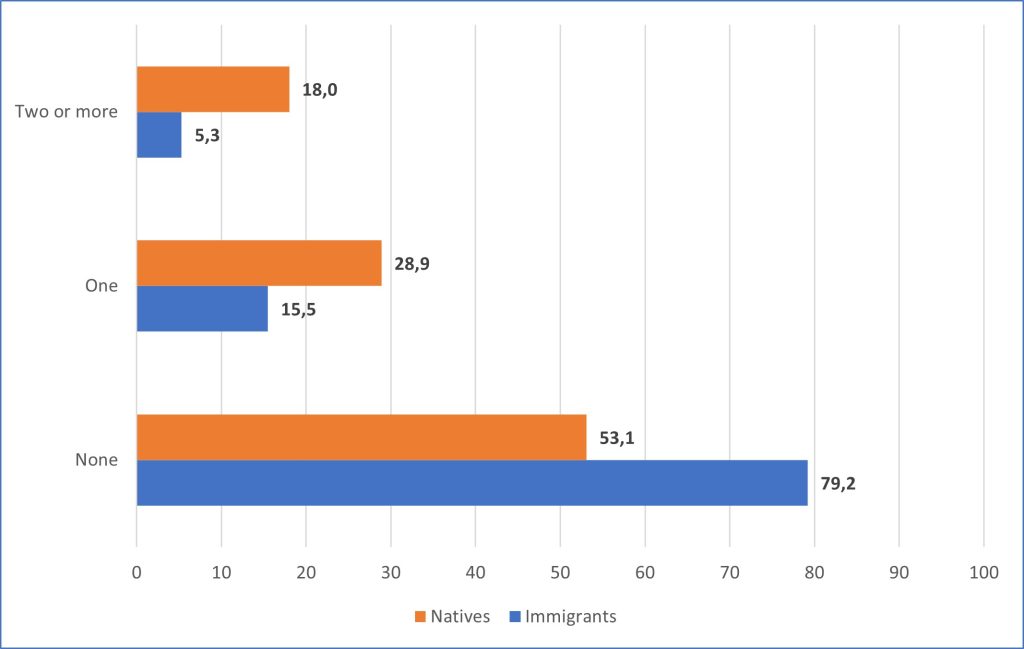

The component of “Activity” is composed of the number of organisations, clubs, or associations the respondent claims to be a member in. One question in the survey asked whether the respondent was a member of: Sport clubs, youth organisations (ungmennafélög), choirs, women’s associations, rescue teams, the Red Cross, organisations such as Rotary or Kiwanis and finally political parties. These can all be considered as quite common in Iceland. The scores for this component increased with a higher number marked. Activity was classified as follows: Membership in none (1), Membership in one (2) Membership in two or more (3). Figure 1 shows the immigrants’ activity. The overwhelming majority of the immigrants in the survey claim membership in no organisation and only about 5 percent in more than one.

Figure 1. Immigrants’ activity measured through membership in various organisations (%).

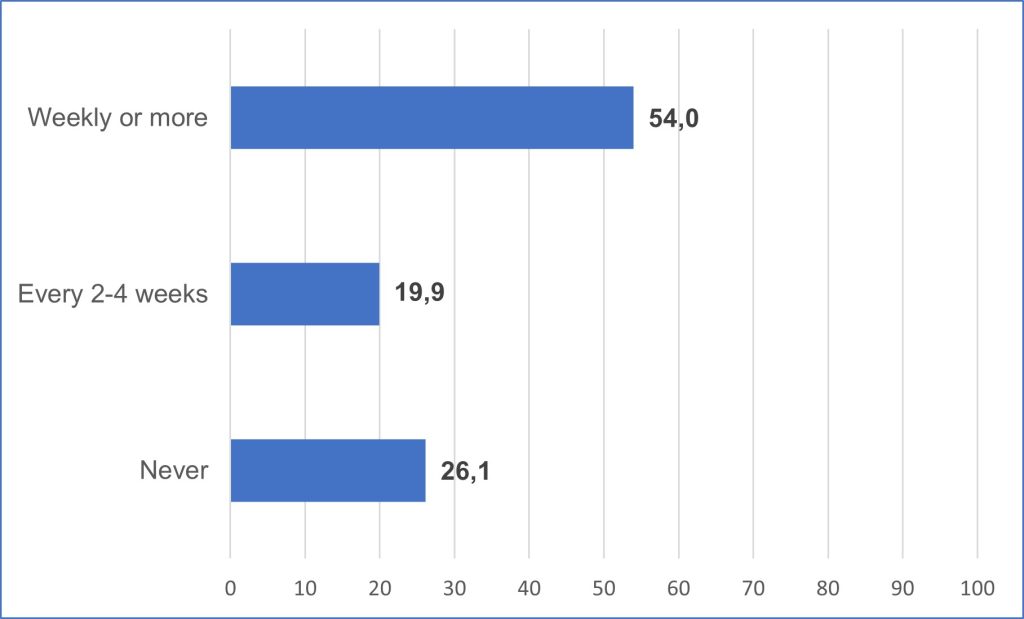

“Use of Icelandic media” comprises answers to a question about the frequency of using domestic media. The classification was: “Never” (1), “Every 2-4 weeks” (2), and “Weekly or more” (3). As figure 2 shows, more than 50 percent of immigrants use Icelandic media weekly or more, while about ¼ never do.

Figure 2. Immigrants’ use of Icelandic media (%).

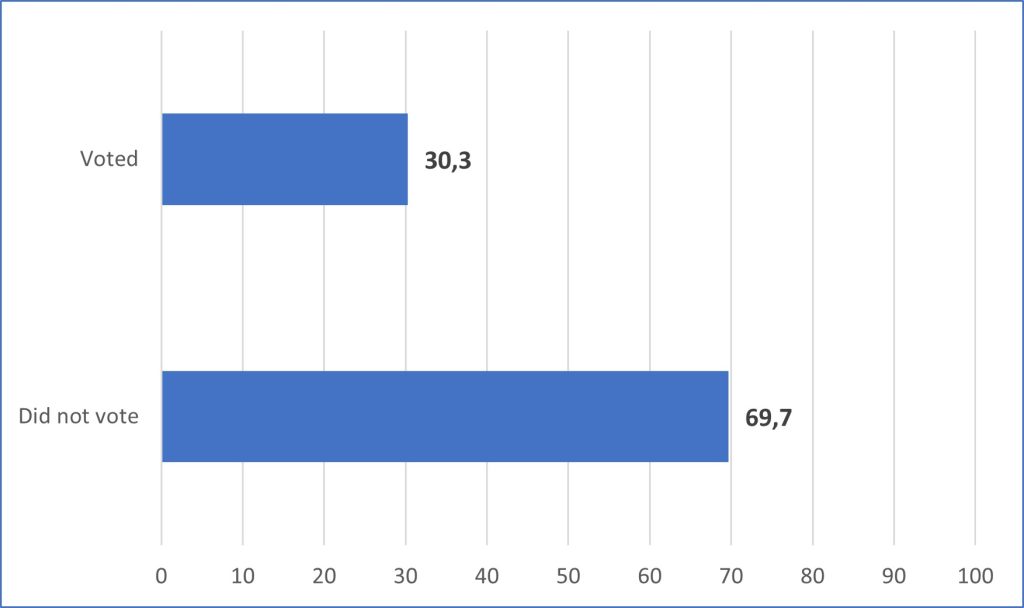

The third component in the Participatory Index is: “Voted in local government elections in 2018”. People were asked whether they voted in 2018 or not. Having voted yielded a score of 3 and not having voted resulted in a score of 1.[1]

Figure 3. Immigrants’ voter turnout in the Icelandic Local government elections 2018 (%).

These are the components building the Participatory Index which spanned the scores between 3 and 9, where a higher score meant more participation in Icelandic civic culture. In this paper we analyse the index by selected background variables collected in the immigrant survey. These are: gender, age, proficiency in the Icelandic language, residency in Iceland and its duration. The Participatory Index was also cross analysed with a Trust Index we constructed from the survey, consisting of answers to questions on trust in the police, the parliament, the Directorate of Labour, trade unions, the school system, and the health system.

- Analysing participation and trust

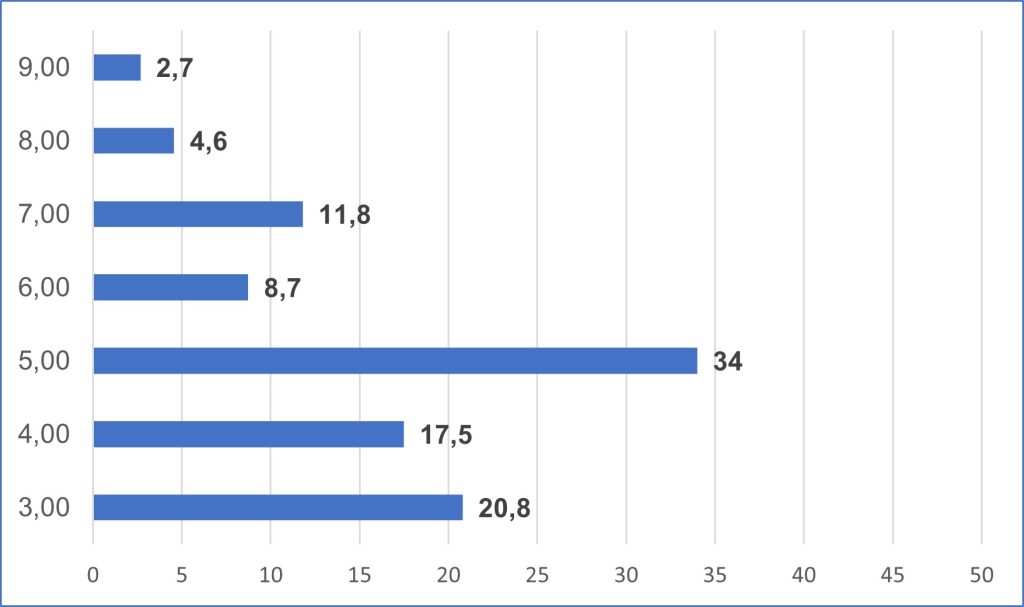

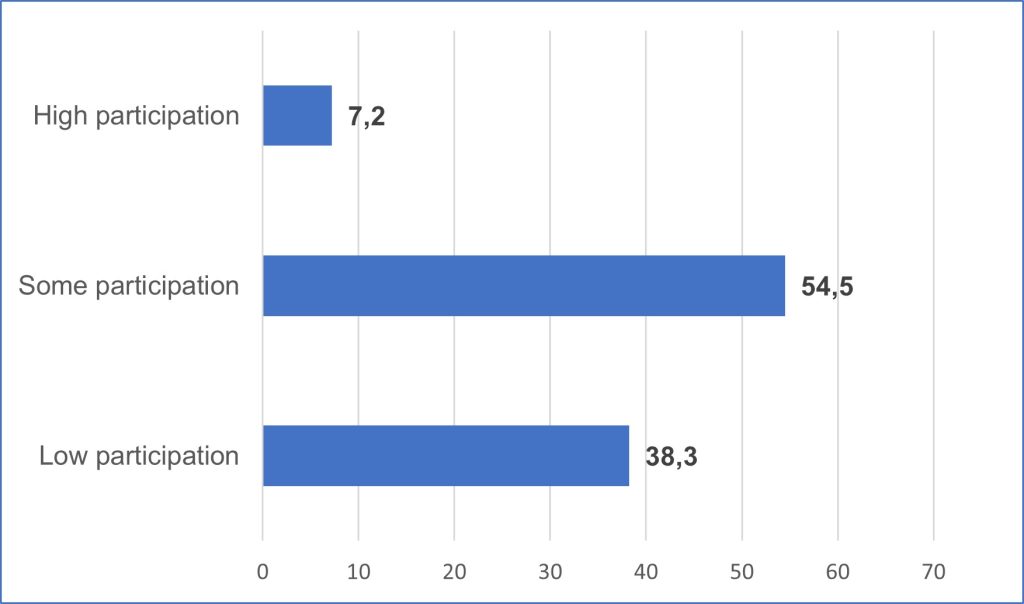

In this section we show our analyses of the scores on the Participatory Index by different background variables. Further, we show the connection between participation and trust. Immigrants in Iceland score quite differently on the two indexes. As figures 4, 5 and 6 indicate, a considerable proportion of the immigrants (38 percent on 3-4) score low on the Participatory Index while very few score high (7 percent on 8-9). The majority of immigrants score neither low nor high (55 percent on 5-7). This indicates that immigrants are rather limited participants in the civic Icelandic culture as far as our index measures it.

Figure 4. Frequency of scores on the Participatory Index for immigrants (%).

Note: The scores range from 3 to 9 where 3 is lowest and 9 highest in participation.

Figure 5. The immigrants’ Participatory Index in three groups (%).

Note: From Figure 4 scores from 3 to 4 are classified „Low“, scores from 5 to 7 as „Some“and scores from 8 to 9 are classified as „High“.

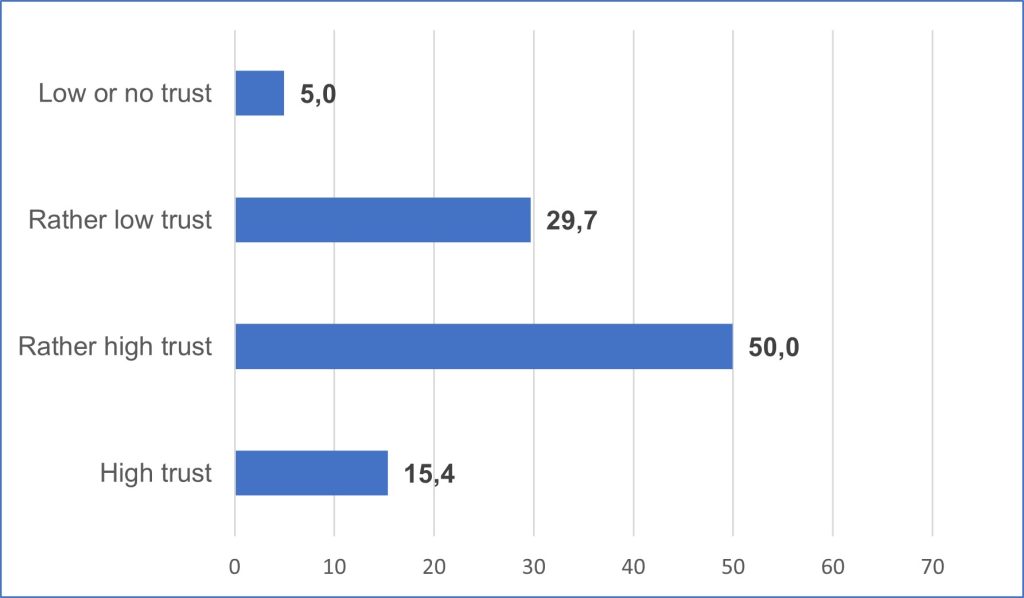

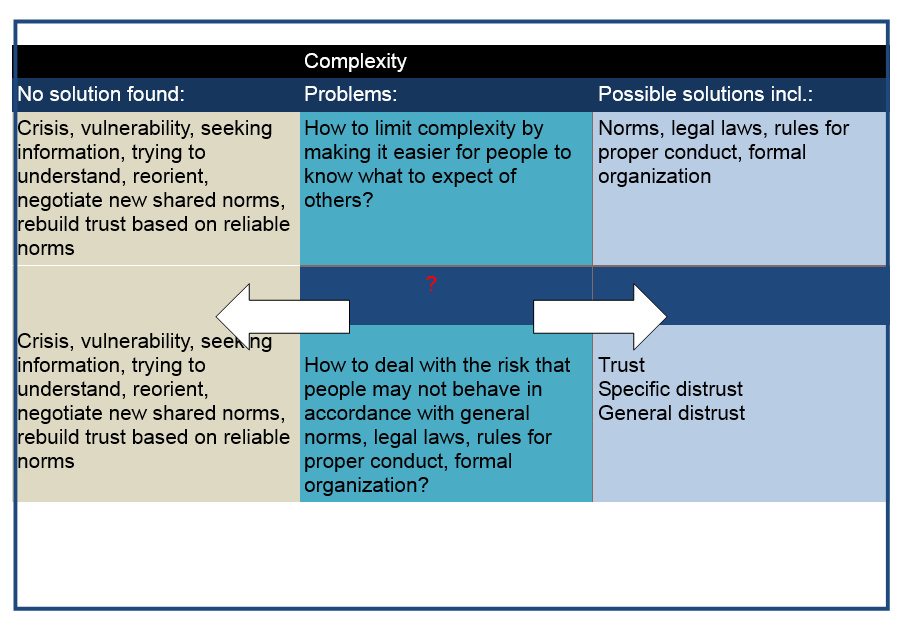

At the same time as the Participatory Index shows low participation of immigrants, it is of considerable interest to note their high or rather high trust in several important institutions of Icelandic society. Figure 6 tells us that almost 2/3 of the responding immigrants show rather high or high trust on our Trust Index. In the survey, people were asked about trust in six institutions and organisations[2] answering on a 1-5 Likert scale where “no trust“ was coded as 1 and „A lot of trust“ was coded as 5. From the questions on the 6 institutions, we constructed a 6-30 scale. The scores were placed in 4 categories as we see in figure 6, with the following values and labels: “Low or no trust“ (6-12), “Rather low trust“ (13-18), “Rather high trust“ (19-24), “High trust“ (25-30).

Figure 6. Immigrants´ trust in Icelandic institutions (%).

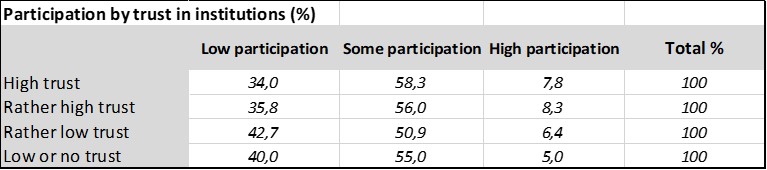

As shown in Table 1 below, we do not see any consistency between the two indexes – that is, participation and trust among immigrants. There is no clear link between high participation and high trust, and we only see a minor connection of that kind.

Table 1. Immigrants’ participation by trust in institutions (%).

- The Participatory Index and background variables

In this section we examine the immigrants’ scores by background variables collected in the survey from 2018. These variables are: Age, gender, length of residency in Iceland, proficiency in the Icelandic language and geographical region of origin. As shown earlier, the scores on the Participatory Index are mean scores on the scale 3 to 9 where a higher score means more participation.

- Age

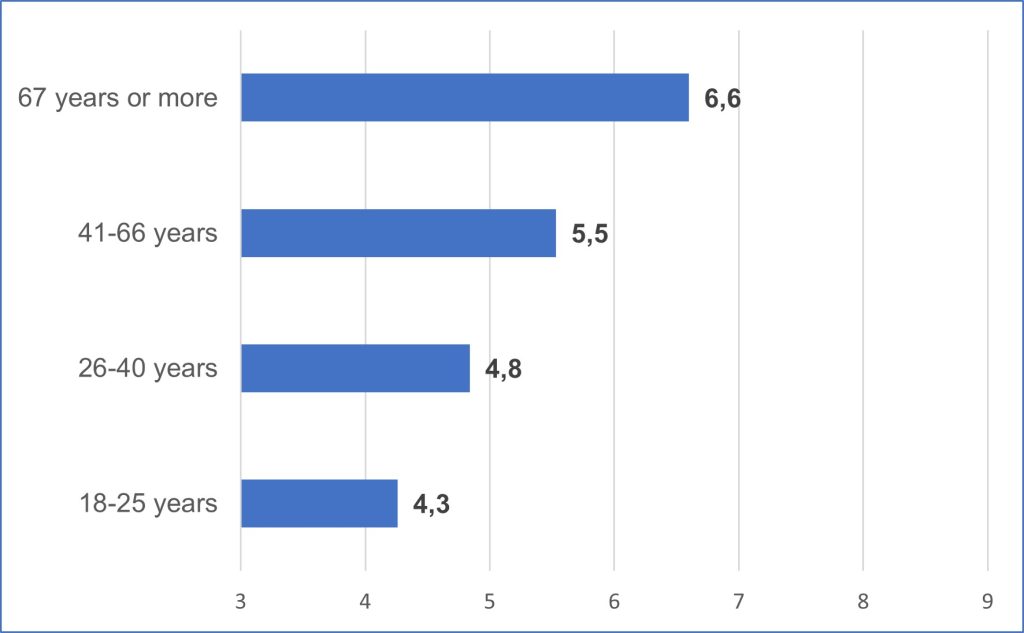

As one might have expected, the age of immigrants influences participation as measured by the index due to connections with longer stay as an immigrant. People above forty score on average higher than the average score of all respondents (5.0). Participation increases with age, with the youngest scoring lowest and the oldest highest (Figure 7). The scores for the oldest group are much higher than the scores for the youngest group, more than 50 percent higher.

Figure 7. The immigrants´ scores on the Participatory Index (3-9) by age.

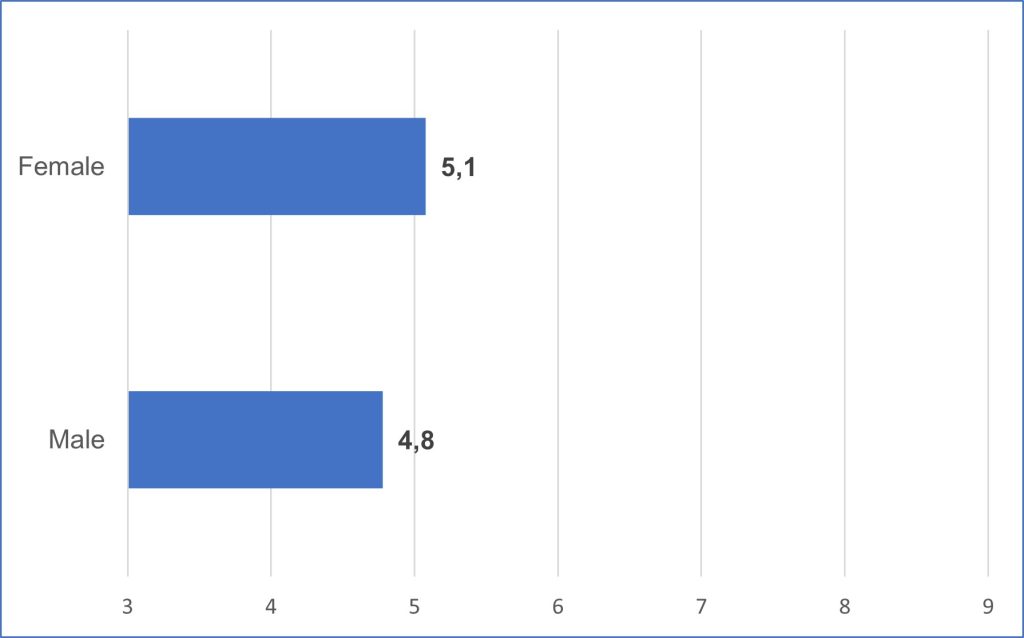

- Gender

The average scores for male and female immigrants are very similar as Figure 8 shows. The numbers for females are slightly higher, but a difference between male and female of 0,3 on the 3 – 9 scale is very little.

Figure 8. The immigrants scores on the Participatory Index by gender.

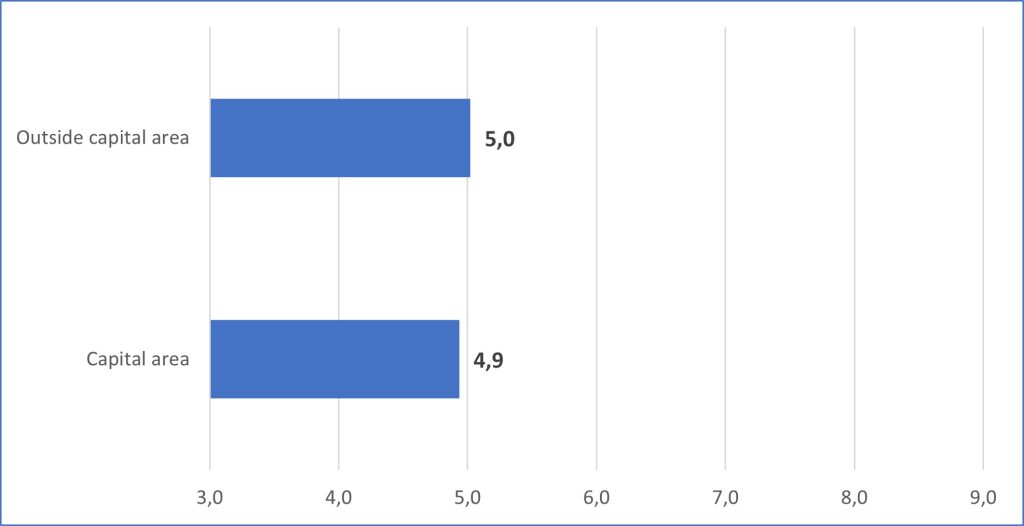

- Place of residency in Iceland

This background variable is of particular interest as it is likely that the place of residence matters regarding participation, in this case whether immigrants lived in sparsely or densely populated areas. The sample size and the spreading of immigrants around the country did not allow us to analyse our material by municipalities and sometimes not even by regions. However, we tried to push the matter further by categorising regions into two sectors: The “capital area” (densely populated, Reykjavík and surroundings) and “outside capital area” (more sparsely populated), the latter being areas with some densely populated municipalities but overall, much fewer inhabitants. As Figure 9 shows, there is almost no difference. These results suggest that it does not seem to matter for immigrants’ participation, social or political, whether they live in urban or more rural and sparsely populated areas.

Figure 9. The immigrants’ scores on the Participatory Index by region of residency.

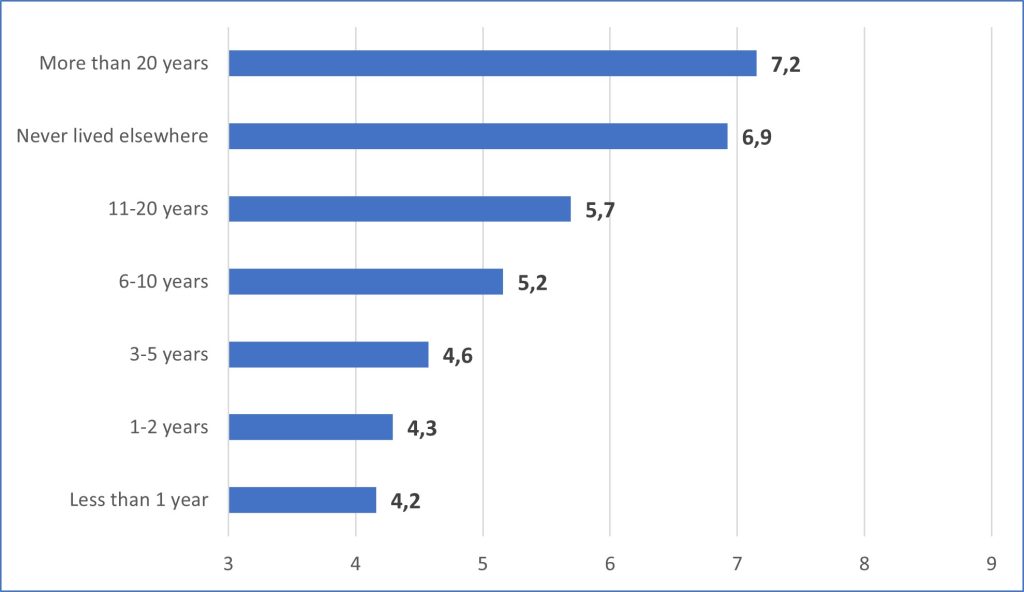

- Length of residency in Iceland

Figure 10 below, clearly indicates that those who have always lived in Iceland or have lived there for more than 20 years are more integrated in Icelandic culture through participation than those who have lived in the country for a shorter period. Scores of 6.9 and 7.2 out of 9 must be considered as quite active participation. The figure also shows that participation, as measured by the index, is closely connected to length of residency in the country. The index scores have a linear increase from the lowest score of 4.2 up to 7.2.

Figure 10. The immigrants´ scores on the Participatory Index by length of residency in the country.

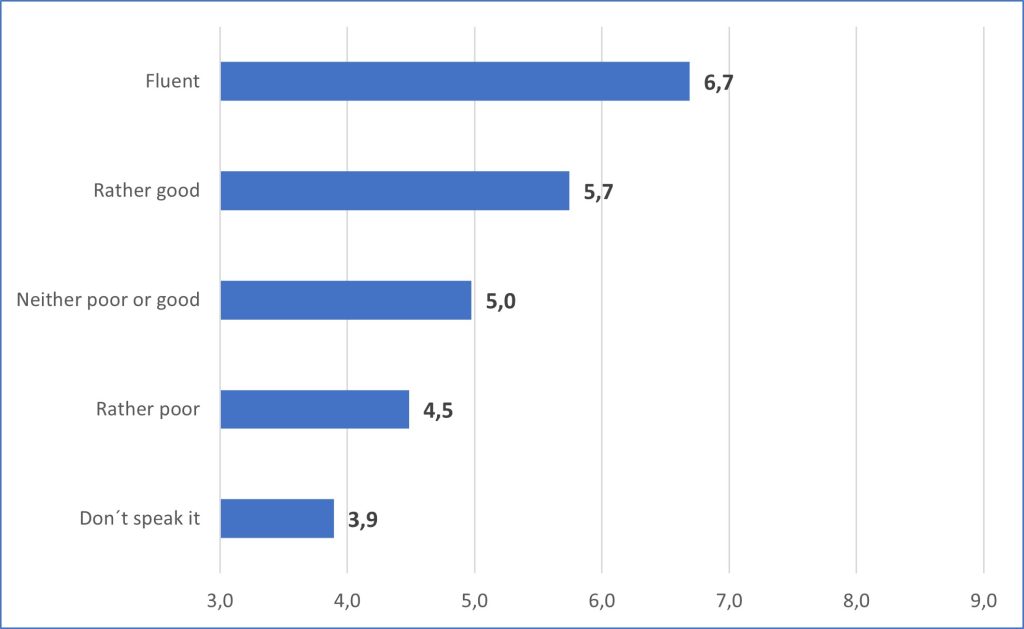

- Proficiency in the Icelandic language

Self-review or estimation of “Proficiency in the Icelandic language” is a background variable of importance. Here too, we see a linear relationship where participation is linked to proficiency in the language. The variation of the scores shows that learning the language is of importance for immigrants to adapt or integrate and that participation is important for learning the language.

Figure 11. The immigrants’ scores on the Participatory Index by own estimation of the proficiency in Icelandic.

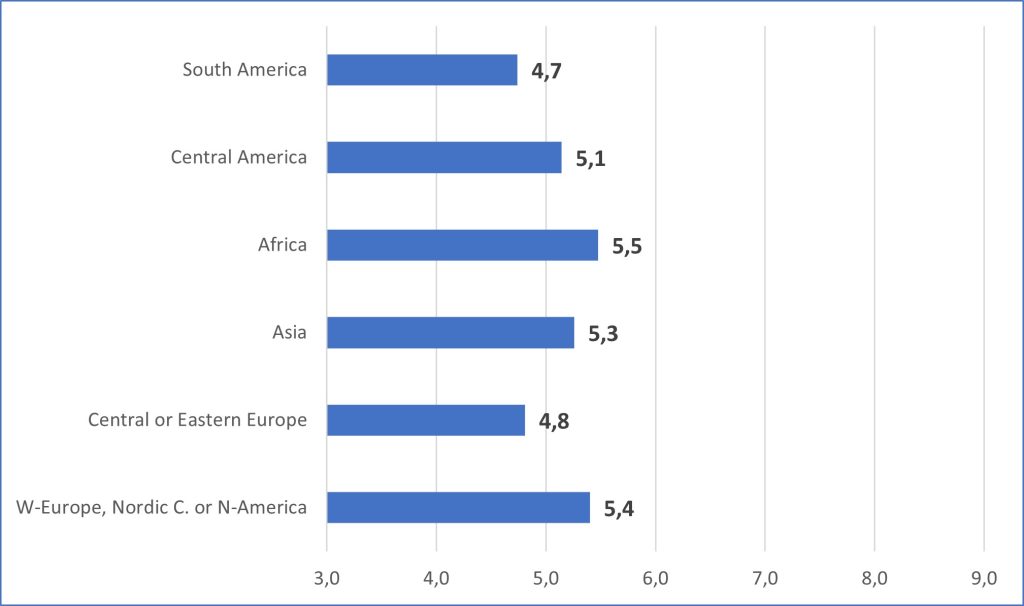

- Country/region of origin

The last background variable we look at is the geographical region of immigrants’ origin. The differences seem to be small. The average scores vary between 4.7 and 5.5 on the 3-9 scale which cannot be considered much – the difference between the lowest and the highest score is 13 percent of the whole scale. However, we can still see that immigrants from South America and Central and Eastern Europe have lower scores, while immigrants from Africa and Western Europe, the Nordic and North America have the higher scores. That is indeed in line with the afore mentioned numbers on a higher voter turnout in 2018 and 2022 elections of Nordic immigrants than other immigrants.

Figure 12. The immigrants’ scores on the Participatory Index by their geographical region of origin.

- Comparing immigrants and natives

At the same time as the immigrant survey was implemented, in autumn 2018, a survey was conducted among a random sample of natives. A stratified random sample of 8100 persons in 12 selected municipalities around the country was asked to participate and 3610 agreed to do so. In terms of gender, the respondents were very evenly represented (51/49 per cent). The average age was about 51 years. Respondents were asked questions about life in Iceland, and, among other things, trust in institutions and activity through membership in organisations. These two questions were identical to those presented to the immigrants. A comparison of the answers to these questions is, therefore, highly interesting, allowing us to place the results for immigrants into context.

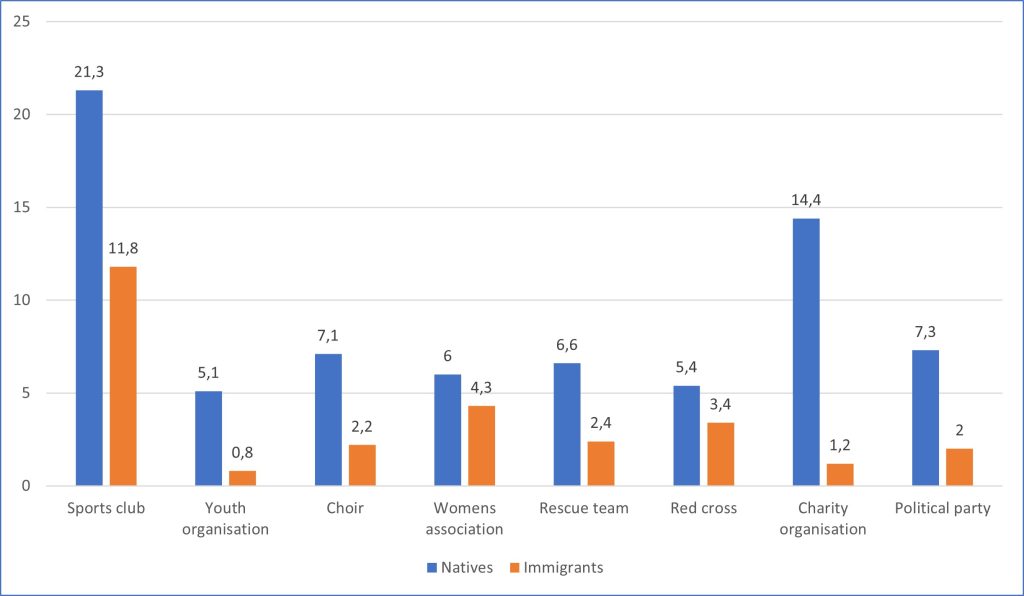

Figure 13 shows membership in selected organisations for both groups. The pattern is the same for all organisations; natives are more active. In most cases they are more active by far, but in three cases the difference is less than double: sports clubs, women’s associations and the Red Cross. In others, the difference is bigger, up to more than tenfold.

Figure 13. Immigrants’ and natives’ membership in organisations (%).

When the number of organisations is simplified into three categories, we see in figure 14 that only just over 20 percent of the immigrants are members of an organisation, while the number for natives is close to 50 percent. The difference is considerable.

Figure 14. Immigrants’ and natives’ membership in organisations – categories (%).

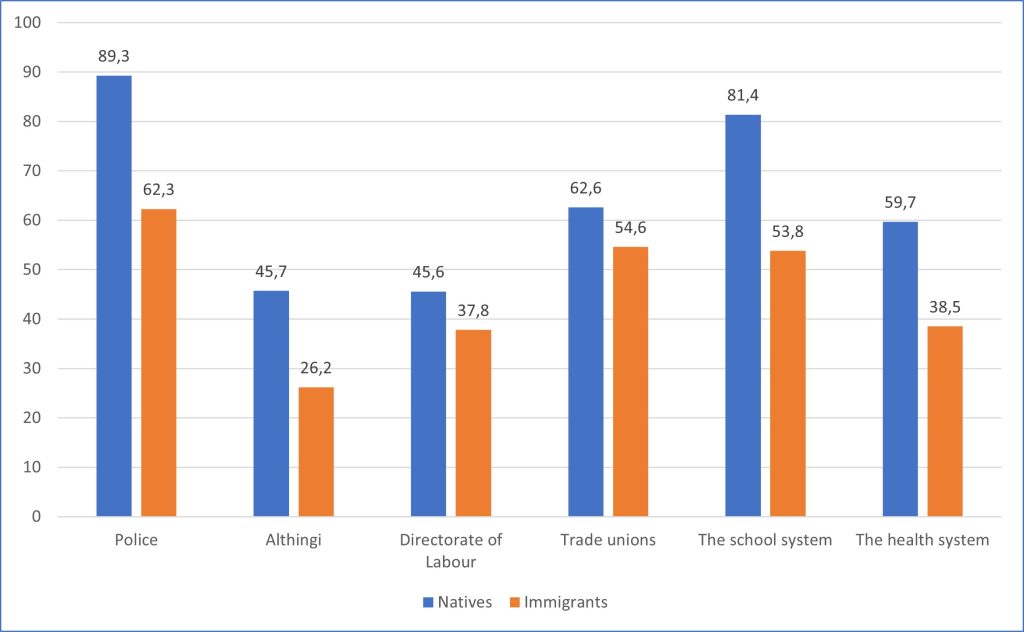

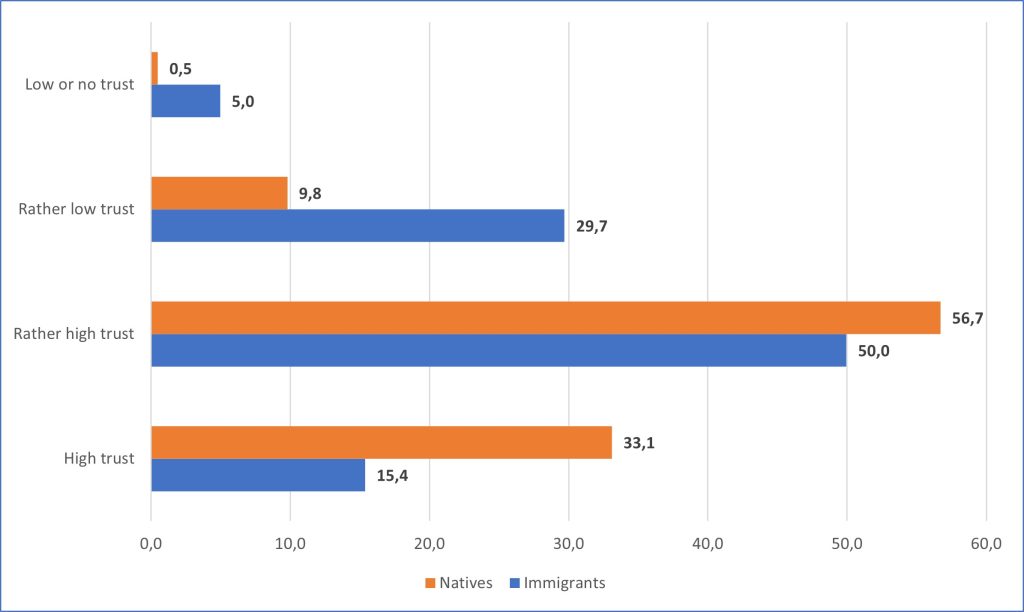

The second variable for comparison is “Trust in institutions”. Trust is not a matter of membership, but membership calls for activity and participation which encourages the build-up of trust in social institutions. Figure 15 shows less trust among immigrants in all the selected institutions. However, the differences are not as great as when comparing participation. The trust in the state run “Directorate of Labour“, and the “trade unions“ differs by less than 10 per centage points. It should be noted that participation in trade unions is very high among Icelanders. In other institutions the difference is 20-30 per centage points.

Figure 15. Immigrants’ and natives’ trust in institutions (%).

When an index of trust is constructed and the difference between the groups is compared, as shown in Figure 16, it appears that, in general, immigrants trust institutions to a lower degree than do natives. The proportion of immigrants expressing high trust is, for example, less than half of that among natives (15 percent / 33 percent).

Figure 16. Immigrants’ and natives’ trust in institutions – categories (%).

To sum up, there is a considerable difference between immigrants and natives when looking at integration through membership in organisations, but the difference between immigrants and natives is less when it comes to trust in institutions. This suggests that immigrants in Iceland have some trust in the Icelandic institutions, though not as much as natives. The survey material does not allow a complete comparison on the indices constructed between natives and immigrants. Not enough data is available to construct the Participatory Index for natives, but only parts of it.

- Discussion

The main results of this study are that immigrants do not participate to any larger degree in Icelandic civic society while their trust in societal institutions is measured as rather high compared to their participation. This was not expected, since theory considers trust as the key to civic engagement and social capital (Putnam, 1992, 2001). We can offer somel explanations of this; for example, that the relationship between trust and civic culture is not a direct one and can be affected by some more complicated factors. Another explanation could be that our indexes for measuring participation and trust do not catch this correlation.

However, even though participatory culture, as defined by Almond and Verba (1989; 1963), has been prominent in Iceland’s political culture, this does not have to be the culture immigrants grew up with in their countries of origin. The fact is that the biggest groups of immigrants in the country come from East-European states where we can say that a subject culture existed under the Soviet regime’s influence. In that period citizens’ level of participation was generally limited by the state, which, despite that, was often trusted to perform basic functions. Indeed, this cultural difference between Eastern Europe and Iceland (and the Nordic countries) has surfaced in different fields, suggesting a complex relationship between trust and the role of government and participation or integration. Studies show that vaccine hesitancy in OVID-19 among Eastern European Immigrants in Iceland and in Norway was considerably greater than among natives. This has been explained with reference to different civic cultures, and complex interaction of economic and social factors, but also partly by the role of the state and distrust of authority by Eastern Europeans, which they import with them to the host country (Meckl et al., 2025; Kour et al., 2022).

Our analysis of immigrants’ participation by using the Participatory Index and several background variables shed light on some items of importance which should be further investigated. Firstly, there is the linear relationship between immigrants’ length of residency in the country, and their age and proficiency in Icelandic, on the one hand, and participation, on the other. It seems apparent that an important acculturation or interplay between immigrants and civil society takes place over time and leads to more participation among immigrants. Mapping this process would be interesting, not only to note how immigrants adapt to national culture and values but also to discover how, or whether, this interplay changes the existing civic and political culture. Indeed, as mentioned in the discussion of Icelandic political culture above, certain moral and liberal values as well as nationalistic and conservative have become more apparent in Iceland in recent years that might be attributed, in part at least, to this interplay. Furthermore, it is not surprising to see that the findings clearly suggest that learning the language is important for participation, while at the same time participation is important for learning the language. The linguistic issue has for a long time been prominent in most discussion on immigrants in Icelandic society. Language appears to be a ticket to the civic culture and participation, an element which is reflected in the patriotic undertone that has historically been evident in Icelandic political culture. Secondly, it is of particular interest to note the conclusion that the residency of immigrants in Iceland – whether they live in the capital area or in the smaller and more sparsely populated communities around the country – does not seem to matter regarding the degree of participation. We see this as an important finding and a valuable contribution to the discussion in Iceland on immigrants in general and quota-refugees specifically. The discussion has quite often been about whether it is better or worse to place refugees within or outside the capital area (Félagsmálaráðuneytið, 2019).

In fact, our analyses and measurements show that a large proportion of immigrants take at least some part in Icelandic society. This indicates that there are no serious defects in the acculturation of immigrants, nor are there – yet at least – emerging new major cleavages in the civic culture in the country. Nevertheless, it needs to be pointed out that “low” and “high” participation is relative. We cannot conduct any broad comparisons with other measurements, such as among native Icelanders, other than the two we presented in the preceding section of this article. Those results, even though not fully comparable, indicate lower participation and lower trust among immigrants than among natives.

In this article, we present indications that participation among many immigrants in civic society and culture could be higher. That, in itself, is a significant research result and a matter for public policymakers to consider ways to increase immigrant participation in Icelandic society. The type of research approach applied in this study, where important variables regarding immigrant acculturation are collapsed into indices, can also have useful implications beyond the Icelandic case, as the question of immigrants’ acculturation is a pressing issue in many countries.

Clearly, there are important limitations to our study. The most pressing ones relate to the fact that we do not have a random sample, which considerably limits the scope of statistical analysis. Also, the indices constitute an aggregate where the component parts weigh more or less equally, possibly missing some finer nuances in their relative importance. Civic culture, in the sense we have chosen to define and use the concept, is a setting for compromises and mediation of different cultural traits. The indices we have used to operationalise the concept of participation and trust may not catch the full content and nature of the culture in Iceland, but they are, however, important indicators.

- References

Adler, R. P., & Goggin, J. (2005). What Do We Mean By “Civic Engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236-253. Retrived from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344605276792

Alencar, A., & Deuze, M. (2017). News for assimilation or integration? Examining the functions of news in shaping acculturation experiences of immigrants in the Netherlands and Spain. European Journal of Communication, 32(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323117689993

Almond, G. og Verba, S. (1989 (1963)). The Civic Culture. Newbury Park, California: Sage Publications Inc.

Anderson, U. (2017) Trust – the Nordic Gold. Nordic Council of Ministers.

Bjarnason, T. (2014) Traust í kreppu: Traust til Alþingis, lögreglu, stjórnmálamanna og forseta Íslands í kjölfar hrunsins. Íslenska þjóðfélagið, 5(2), 19-38. Retrieved from https://www.thjodfelagid.is/index.php/Th/article/view/67

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In: J. Richardson (ed.), Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education (bls. 241–58). Westport, CT: Greenwood. Retrieved from: http://www.socialcapitalgateway.org/content/paper/bourdieu-p-1986-forms-capital-richardson-j-handbook-theory-and-research-sociology-educ

Dalisay, F. (2012). Media Use and Acculturation of New Immigrants in the United States, Communication Research Reports, 29:2, 148-160, DOI: 10.1080/08824096.2012.667774

Doolittle, A., & Faul, A. C. (2013). Civic Engagement Scale: A Validation Study: A Validation Study. Sage Open, 3(3).Retrived from: https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013495542

Einarsdóttir T J, Heijstra T M & Rafnsdóttir G L (2018). The politics of diversity: Social and political integration of immigrants in Iceland. In: Icelandic Review of Politics and Administration. Special Issue on power and democracy in Iceland (131-148). DOI: https://doi.org/10.13177/irpa.a.2018.14.1.6

Einarsson E. B. (2009). Hið huglæga sjálfstæði þjóðarinnar. Áhrif þjóðernishugmynda á Evrópustefnu íslenskra stjórnvalda. Retrieved from https://skemman.is/bitstream/1946/10829/1/Phd_eirikur_endanlegt%283%29.pdf

Eyþórsson, G. T. (2019). Samfélag án aðgreiningar? Kosningaþátttaka innflytjenda á Íslandi 2017 og 2018. Frumskýrsla. Rannsóknasjóður. Háskólinn á Akureyri. Retrieved from https://www.unak.is/static/files/pdf-skjol/2019/kjorsokn-innflytjenda-agust_2019.pdf

Eyþórsson, G. T. (2020). Kjörsókn innflytjenda á Íslandi 2017-2018. In: Meckl, M. H. And Gunnþórsdóttir, H. (eds.): Samfélag fjölbreytileikans. Samskipti heimamanna og innflytjenda á Íslandi. Háskólinn á Akureyri. (p. 72-79) Retrieved from https://opinvisindi.is/handle/20.500.11815/2402

Evrópuvaktin (2015). Ákvörðun ríkisstjórnar tilkynnt ESB: Ísland er ekki lengur í hópi umsóknarríkja. Retrived from: http://evropuvaktin.is/stjornmalavaktin/35098/

Félagsmálaráðuneytið (2019). Skýrsla nefndar um samræmda móttöku flóttafólks. Félagsmálaráðuneytið.

Fukuyama, F. (2001). Social Capital, Civil Society, and Development. Third World Quarterly 22(1), 7–20.

Gallup (2021) Gallup Iceland, website. https://www.gallup.is/frettir/traust-til-heilbrigdiskerfisins-tekur-stokk-milli-ara/

Guðmundsson, B. (2021) Political communication in a digital age. Defining new characteristics of the Icelandic media system. Ph.D. thesis. Faculty of Political Science, University of Iceland.

Guðmundsson B. & Eyþórsson G. T. (2020). Félagsleg og pólitísk þátttaka innflytjenda á Íslandi. In: Markus Meckl og Hermína Gunnþórsdóttir (eds.) (2020): Samfélag fjölbreytileikans. Samskipti heimamanna og innflytjenda á Íslandi. (bls. 62-71). Retrieved from https://opinvisindi.is/handle/20.500.11815/2402

Hagstofa Íslands. (2024). Innflytjendur 18,2% íbúa landsins. Retrieved from https://hagstofa.is/utgafur/frettasafn/mannfjoldi/mannfjoldi-eftir-bakgrunni-1-januar-2024/

Hagstofa Íslands (2025). Alþingiskosningar 30. Nóvember 2024 (General elections to the Althingi 30 November 2024). Hagtíðindi (Statistical Series).

Harðarson Ó. Þ. (2008). Political Communication in Iceland. In: J. Strömback, M. Örsten og T. Aalberg (eds.), Communicating politics. Political Communication in the Nordic Countries. Gothenburg: Nordicom.

Harðarson, Ó. Þ. and Helgason, A. F. (2024) „Tímans þungi niður. Þjóðfélag og flokkakerfi í hundrað ár.“ In ed. Þórhallsson,B. (2024) Lognmolla í ólgusjó. Háskólaútgáfan.

Helgason, A. F. and Þórisdóttir, H. (2024). Með eða á móti? Tengsl stjórnmálaviðhorfa og kosningahegðunar. In ed. Þórhallsson,B. (2024) Lognmolla í ólgusjó, Reykjavík, Háskólaútgáfan.

Hjartarson S. (1952). Marz 1949. Á Gnitaheiði. Reykjavík: Heimskringla.

Hoffman, L., Bjarnason, T. and Meckl, M. (2020). Regional differences in the inclusion of immigrants in Icelandic society. In: Markus Meckl og Hermína Gunnþórsdóttir (eds.) (2020): Samfélag fjölbreytileikans. Samskipti heimamanna og innflytjenda á Íslandi. (bls. 80-90). Retrieved from https://opinvisindi.is/handle/20.500.11815/2402

Hogeby, L (2006). Hvorfor er den politiske deltagelse blandt etniske minoriteter i Danmark så forholdsvis høj? In: Bortom stereotyperna? Invandrare och integration i Danmark och Sverige (2006) Serie: Centrum för Danmarksstudier nr 12. Göteborg & Stockholm. Makadam Förlag.

Jamal, A.; Kizgin, H.; Rana, N.P.; Laroche, M.; Dwivedi, Y.K. (2019). Impact of acculturation, online participation and involvement on voting intentions, Government Information Quarterly, 36:3, 510-519

Jónsdóttir, V., Harðardóttir, K. E. and Garðarsdóttir, R. B. (2009). Innflytjendur á Íslandi. Viðhorfskönnun. Reykjavík. Félagsvísindastofnun og Fjölmenningarsetur.

Kleven Ø, Bergseteren T, Risberg T & Corneliussen H M (2022). Innvandrere og stortingsvalget 2021. Stemmeberettigede, valgdeltakelse, partivalg og representanter. Statistisk sentralbyrå.

Kour P, Gele A, Aambø A, Qureshi SA, Sheikh NS, Vedaa Ø, Indseth T. (2022) Lowering Covid -19 vaccine hesitancy among immigrants in Norway: Opinions and suggestions by immigrants. Front Public Health. Nov 16; 10:994125. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.99412.

Meckl, M. and Gunnþórsdóttir, H. (2020). Inngangur. In ed. Meckl, M, and Gunnþórsdóttir, H. Samfélag fjölbreytileikans. Samskipti heimamanna og innflytjenda á Íslandi. Rannsóknarsjóður, Háskólinn á Akureyri

Meckl, M; Guðmundsson, B.; K. Ólafsson; Barillé, S. (2025). Munurinn á bólusetningarhegðun innflytjenda og innfæddra Íslendinga í COVID-19 faraldrinum. Læknablaðið, 07.08. tbl. 111

Müssig, S., & Okrug, I. (2024). Discrimination and civic engagement of immigrants in Western societies: A systematic scoping review. Journal of International Migration and Integration. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-024-01154-9

Platform for the Coalition Government of the Social Democratic Alliance, the Reform Party and the People’s Party 2024. Retrived from: https://www.government.is/library/05-Rikisstjorn/Platform-for-the-Coalition-Government_21-December-2024.pdf

Putnam, R. (1993). Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N J: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Portes, A. (1998). Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24, 1–24.

Rothstein, B. and Stolle, D. (2008). The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust. Comparative Politics, 40, 441-459.

Seo, M. & Moon, S. (2013). Ethnic Identity, Acculturative Stress, News Uses, and Two Domains of Civic Engagement: A Case of Korean Immigrants in the United States, Mass Communication and Society, 16:2, 245-267, https://DOI: 10.1080/15205436.2012.696768

Sigurðardóttir, K. and Þórisson, A. (2023) 26.000 raddir sem ekki heyrast. Kveikur, Retrived from: https://www.ruv.is/frettir/innlent/2023-09-12-26000-raddir-sem-ekki-heyrast-422489

Sime, D., & Behrens, S. (2023). Marginalized (non)citizens: migrant youth political engagement, volunteering and performative citizenship in the context of Brexit. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 46(7), 1502–1526. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2022.2142061

Statistiska Centralbyrån (2015). Vilka valde att välja? – Deltagandet i valen 2014. Statistiska Centralbyrån. Demokratistatistik 19.

Statistiska Centralbyrån (2023). Delat deltagande En studie av integration och segregation baserat på valdeltagande i 2022 års allmänna val. ME09 – Demokratistatistik 2023:2.

Statistics Iceland (2018). Innflytjendum heldur áfram að fjölga. Retrived from: Mannfjöldi eftir bakgrunni 2018 – Hagstofa Íslands

Statistics Iceland (2025), Innflytjendur 18,9% íbúa landsins. Retrieved from: https://hagstofa.is/utgafur/frettasafn/mannfjoldi/mannfjoldi-eftir-bakgrunni-1-januar-2025/

Sölvason Ó H and Meckl M (2019). Samfélög án aðgreiningar: Viðhorf innflytjenda á Íslandi til símenntunar og íslenskunámskeiða 2018. Háskólinn á Akureyri. https://www.unak.is/static/files/pdf-skjol/2019/samfelog-an-adgreininga

Timmermans M. (2018) Media Use by Syrians in Sweden: Media Consumption, Identity, and Integration. In: Karim K., Al-Rawi A. (eds) Diaspora and Media in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65448-5_3

Vilhelmsdóttir, S. & Kristinsson, G. H. (2018). Political trust in Iceland: Performance or politics? Icelandic Review of Politics & Administration, Vol 12:1, 211-233.

Zhang, Y., You, C., Pundir, P., & Meijering, L. (2023). Migrants’ Community Participation and Social Integration in Urban Areas: A Scoping Review. Cities. 141, Article 104447. DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2023.104447

Þórisdóttir H. (2012). The left-right dimension in the minds of Icelandic voters 1987-2009. Stjórnmál & stjórnsýsla (2)8, 199–220.

Endnotes

[1] In this question people could mark the answering alternative „Did not have the right to vote“. Those who answered with that were excluded from further analysis of voting participation.

[2] The institutions/organisations were following: Police, the Parliament, the Directorate of Labour, trade unions, the school system and the health system.