This article reexamines the prehistoric Hossa-Värikallio site through parallels between rock art, sacred landscapes and Sámi cosmology, particularly shamanistic practices, beliefs and worldview, as illustrated at the site and on seventeenth century drum landscapes. Adopting a comparative narrative approach, I identify a number of important correlations between the shamanistic séance illustrated on the boulder formation at the Hossa paintings and the significance of sacred structures on seventeenth century Sámi drum landscapes with regard to their spiritual significance in connection with the theory of sacred multifaceted relationships as both cultural and identity markers.

In terms of development of rock art research, in 2007, I published research on prehistoric rock art at Hossa and ethnographic parallels with Sámi cosmology from the seventeenth century. The article titled, “Shamanism and Rock Art – The Dancing Figure and the Stone Face at Hossa, Northern Finland[1] analysed sacred prehistoric rock paintings at the Hossa-Värikallio site located 100km northeast of the town of Suomussalmi in northern Finland. The Hossa site is also approximately 80km southeast of the town of Guossán/Kuusamo, which much earlier was a Forest Sámi settlement area.[2] The site contains rock art as dated by Taavitsainen (1979 in Niskanen 2017: 10) who used “stylistic comparisons in dating the Värikallio paintings to the end of the Stone Age, from 2500-1500 BCE, or between the Late Comb Ceramic and Early Metal Periods.” The painted area above Lake Somerjärvi is a threshold area that constitutes a sacred space. The painted area has been painted across different time periods as superimpositions, indicating that it has a sacred function as a mythical landscape containing sacred narratives related to an ancient shamanic séance.

The research paper from 2007 attempted to highlight the new discovery of a large stone face to the left side of the painted panel. Resembling an old man, the naturally formed face could be an ancient local god or guardian (sieidi in the north Sámi language). Stone figures as such are a well-known phenomenon in pre-Christian Sámi religion and culture. The presence of this figure helped me understand why this abode may have had significance as a sacred site and, therefore, was chosen to create rock paintings upon as a method for constructing cultural narratives. Regarding the decoration of the Hossa boulder formation:

“The painting has been executed on a rock wall plunging perpendicularly into the lake, over an area of some 10.5 meters long. The lowest figures are only about 20cm, and the highest ones are some 2.5 meters above the present surface of the lake. […] More than 60 painted figures have been identified on the rock wall”. (Taskinen 1999: 2).

In 2005, two questions emerged during and after a visit to the Hossa site. Firstly, was the boulder formation on which the narratives are painted a cosmological representation of a sacred mountain or cliff with a lake at its base? This question is salient, given how the mountains in Finland are in Lapland and, thus, tied to Sámi religion and cosmology and also how different spirits inhabit mountains, cliffs and the bottoms of lakes, namely the Sáivo world. And, secondly, what is the identity of the central figure resembling a werewolf among human and animal figures engaged in movement as if dancing? In addition, considering the ethnographic parallels with Sámi cosmology, two interviews featured in the publication. The first interview was with Sámi elder Oula Näkkäläjärvi who lives in the Inari municipality in Finnish Sápmi. The interview concerned the werewolf figure and the two stick-like figures with triangular-shaped heads who seemed larger and somewhat animated above the central figure and other animals on the panel. I also included an interview with Alpo Rissanen who worked at Jalonniemi House as the tourism manager. The interview with Rissanen focused on local Sámi culture and history.

The purpose of my approach at the time was to link the content of the painted panel from prehistory with “[…] a shamanic ceremony related to hunting and animal ceremonialism” (Joy 2007: 77). Sámi mythical landscapes, totemism, rituals, beliefs, structures and practices from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were illustrated on sacred Sámi drums and described in early missionary texts.[3] Forest Sámi settlements in the Kainu district where the Hossa site is located are confirmed by the name of the location. The name Hossa in the Sámi language means “a faraway place” (Rissanen 2006: 1) and also has a Finnish etymology meaning “the place where ‘horse’s tail’ grows, something common to most lakes in the Hossa area” Alpo Rissanen further explained that, “The fact that there is a Saami place name for that site indicates the previous residency by Saami inhabitants” (Rissanen cited in Joy 2007: 82).

For the ancient ancestors of the Sámi who hunted, fished and trapped, “in the northern part, there are sandy ridges [pathways] that the reindeer have travelled on; they go to the west of the Hossa area and there are also holes in the earth that were used for hunting” (Rissanen cited in Joy 2007: 82).

Since the 1960s, over one hundred rock art sites have been discovered in Finland. Many of these sites contain animistic landscapes evocative of elements of Sámi cosmology from the seventeenth century depicted on sacred Sámi drums. According to the latest inventory by rock art researcher Ismo Luukkonen, “the total number of confirmed rock painting sites in Finland is 123” (Luukkonen 2024).

The Hossa-Värikallio rock painting is one of the northernmost sites. Its content is unique because it exhibits elements connected to the origin of Sámi shamanic practices and, thus, pre-Christian worldview. The artwork at Hossa portrays human relations with non-human societies and the powers of nature. Since the publication of my research into the ethnographic parallels between rock paintings in Finland and Sámi cosmology from the seventeenth century at the Hossa site, I have published extensively on the subject (see, for example, Joy 2014, 2016b, 2017 and 2018). My work has followed that of earlier Finnish scholars who noticed similar ethnographic parallels between rock art in Finland, shamanism, Sámi religion and related practices (see Luho 1971, Siikala, 1981, Núñez 1995, Lahelma 2005, 2006, 2008a, 2008b and 2012).

On Finnish rock paintings, archaeologist Helena Taskinen (1999: 2) explains that:

“The figures have been painted with red ochre paint. The exact composition and preparation method of the paint is still unknown. It was probably made from iron oxide by heating and adding fat, blood, and possibly also egg as a binder. The red ochre figures have been preserved by a film of siliceous oxide that has formed over them”.

The main research questions

Regarding further analysis of the Hossa site: What do additional ethnographic parallels between the Hossa site as a sacred landscape and the figures painted on the panel reveal about links to Sámi pre-Christian religion and cosmology from the seventeenth century?

The Hossa site was earlier assessed as sacred because of the presence of the large stone face in the rock to the left of the paintings (Joy 2007). Also, the position of the paintings on the rock just above the lake indicates that multiple considerations for creating rock art within a sacred place. Cosmologically, the painting could represent a sacred mountain or cliff because it is well known in Sámi culture that people connect to gods through offerings to landscapes. It is also significant that the area is in the centre of the location. Henceforth, comparing new correspondences between the two sources of art and historical periods builds on the research from 2007. The current study aims to incorporate additional considerations of Sámi shamanism and cosmological landscapes associated with pre-Christian Sámi religion and, thus, attempts to build a more comprehensive view of the site.

Aims of the research

The re-examination of the position of certain painted figures and landscapes at the Hossa site are central to the current study. Photographs and illustrations linked to the Hossa site and Sámi noaidi drums from the seventeenth century help shed further light on the importance of these significant landscapes.

The initial focus of my analysis considers the research ethics used when engaging with Sámi culture and history. Therefore, I have attempted to assess new features of the Hossa site in a respectful way to establish earlier links between the site and Sámi cosmology. According to the Hossa panel, the site appears to have been a meeting place between humans and the souls of animals and ancestors.

The rock itself could be representative of a mountain or cliff because mountains in Finland are in the far north of Lapland and, thus, connected to the Sámi. Secondly, there is the question of the relationship between the dancing therianthropic figure and the human figure who appears to be rising from below. To follow, how might the large deer or elk located at the top of the painted panel be significant in relation to astral mythology? Furthermore, what does the recent discovery of what looks like a human figure playing a drum mean in relation to the content of the panel? Finally, what are the possible identities of both triangular-headed stick figures which look like spirit figures from Sámi drum landscapes as well as fish-like figures who appear to be rising from just above the surface of the lake? What could these mean in Sámi cosmology?

A new study of the painted drum landscapes and rock art panel at Hossa suggests the creation of art for shamanic purposes. A new analysis strives to help:

[…] illustrate the special importance of the shaman and his drum for preserving the necessary balance between the three levels of the cosmic order. […] The shaman was considered to be a great specialist in the geography of the other world or rather an altered state of consciousness made possible by the trance. During this phase, the soul of the shaman was supposed to be transformed into the shape of a bird, a fish, a wolf, a bear, etc. (Pentikäinen 1987: 19).

Furthermore, the present study aims to enhance understanding of what it means when:

“The definitive separation of the soul from the body causes death, but [how] certain persons, especially the professional shamans, the noaidi, possess the faculty of detaching their soul occasionally from the body, allowing it to make alone journeys to distant places, among other things to the land of the spirits. Very great importance is attached to these journeys of the shamans” (Karsten 1955: 57).

The activities of drum use and dance for example are built around social structures and inter-species communication in a multitude of different contexts that reflect creation myths. Cultural narratives are linked to spiritual beliefs and practices.

Approach and methods used in the research

The purpose of undertaking research at the Hossa location is to re-examine the site in a broader, holistic way using narrative and comparative methods. I designate local-regional traditions (Sámi) as a priority and make comparisons between different time periods, notably, prehistory and the seventeenth century. It is important to point out societal and cultural relevance when developing theories about links between art and different historical phases. The ethical approach of the research is governed by “the single and overriding belief shared amongst Indigenous Religions [which] derives from a kinship-based worldview in which attention is directed towards ancestor spirits as the central figures in religious life and practice” (Cox cited in Tafjord 2013: 222). This is because, as already noted, there are established links between rock art and Sámi culture in other Nordic countries as well as on the Kola Peninsula, in north-west Russia, and on seventeenth-century drum landscapes.

By drawing on Sámi shamanism and cosmology to reinterpret the Hossa site, my aim is to present a more comprehensive view of the figures present on the panels because of the amount of research available about the pre-Christian religion of the Sámi people.

Narrative and comparative research methods are outlined as follows. My selection of a narrative method reflects the creation of rock art landscapes as well as noaidi drum landscapes organized into multiple narratives to transmit different perspectives on reality. The noaidi as a ritual specialist is an artist and storyteller. Data in the form of photographs and illustrations captures the ways in which “narrative research is, consequently, focused on how individuals assign meaning to their experiences through the stories they tell” (Moen 2006: 5). Moreover, in the sociocultural context of Sámi traditions further understanding is gained into how the Hossa site and noaidi drum landscapes when translated into art become “stories [that] cannot be viewed simply as abstract structures isolated from their cultural context. They must be seen rooted in society and as experienced and performed by individuals in cultural settings” (Bruner cited in Moen 2006: 5).

What I attempt to communicate through a comparative approach is how social memory and regional identity are crucial because of the number of analogies between the Hossa panel and the noaidi drums. In both cases, art is confined within sacred landscapes that demonstrate relationships between the phenomena despite varying styles. A comparative approach aims to create dialogue:

Comparative analysis is thus central to art-historical inquiry, and its core methodological principle as well for conservation and conversation science both of which play a significant role in characterizing the art object itself and in classifying it relative to its place in the art historical context […] (Coddington2014: 1).

Through the narrative and comparative framework, despite difficulties because of the age of the site, I suggest connections to Sámi shamanism from the seventeenth century.

Figure 1. This is one of the most elaborate painted scenes found to the present date in Finland. The painted panel is at the Hossa site overlooking lake Somerjärvi. Photograph and copyright Pekka Kivikäs (1997).

Earlier studies of the Hossa site: Possible interpretations of rock art figures

Finnish scholar and artist Antero Kare in his analysis of the Hossa site asked whether the painted panel “[…] is a depiction of a shamanistic rite, or is it a depiction of the inner experience of a shaman on his cosmic journey and fantasies?” (cited in Kare 2000: 106). Kare likewise, interprets the wolf-like figure and surrounding animals as dancing.

On the other hand, Helena Taskinen (1999: 3) notes how “the other main attraction of the cliff wall is undoubtedly the horned human figure that appears to be moving. Could this be a shaman dressed in a fur cloak?”.

Analysis of the Hossa site by rock painting researcher Pekka Kivikäs also suggests an association between the wolf-like figure and shamanism. Accordingly, “[…] The horns and ears which have been painted on the person’s head symbolize that the person belonged in the elk family or tribe, but at the same time it can be a symbol of someone being a shaman” (Kivikäs 1997: 31)[4]. In a later publication, Kivikäs (2001: 154) refers to the dancing figure on the Hossa panel as being “[…] dressed in animal skin”.

In terms of parallels between the Värikallio site and Sámi settlement. Karen Niskanen (2017: 10) suggests that:

“The images at Värikallio have their closest thematic parallels in the petroglyph sites in Northern Norway (at Alta), in the Kola Peninsula (at Lake Kanozero and at Calmn Vaara on the River Ponoy), and on the White Sea (on the River Vyg […]. here are also similarities between Värikallio images with those found at Lake Onega in Russian Karelia and the petroglyphs of Nåmforsen in Sweden”.

Robert Layton (2012: 439) states that “one of the most important developments to have taken place in rock art studies is the acceptance by archaeologists that rock art often continues to have cultural significance for Indigenous communities.” Equally, I strive to avoid the pitfalls “where we only theorize how rock art is a product of culture, and where we have no knowledge or understanding of its cultural context, [can mean] our appreciation of rock art is inevitably impoverished” (Layton 2012: 439).

A new theory of the Hossa-Värikallio rock painting

The landscape in the picture above shows the site located above the lake where a richly decorated large boulder formation is evident. To establish if the lake is a Sáivo lake, I would need to consult someone from the Sámi community.

The whole rock area could be representative of a sacred mountain or cliff on which a cosmic structure has been illustrated that consists of different beings and activities. Despite being at an angle, the large fracture through the rock could play an important part in this structure that symbolically traverses and unites the water and the rock. Representative of the lower realm of the cosmos, the area on the panel where dancing is taking place provides a portrait of the middle world whereas the large deer or elk on the panel represents the celestial upper world.

From observation of Ismo Luukkonen’s photographic work at the Hossa site (2021, pp. 278), the crack in the rock is one of the larger ones in the natural formation and expands from left to right. This might be significant as to why it was chosen. Moreover, the left side of the rock begins near the large stone anthropomorphic face.

In the Sámi culture, it is well known how “nature was regarded as animated: each important feature, mountain, hill, lake, waterfall, grazing area, etc., had its own spirit as a local deity” (Whitaker 1957: 296). In addition, Whitaker (1957: 296) claims that “the gods were worshipped in the form of remarkably shaped stones or cliffs called seiteh (singular seite) […]”. What is evident at the Hossa site is a constellation of features that include the location itself as a sacred place containing a representation of a holy mountain, cliff, a holy lake and local deity personified in stone. These correspond to the concentration of “a personified ruling power” (Whitaker1957: 295). Equally, at the Hossa site, we find other concepts that resonate with Sámi sacred places such as “Passe […] a sanctuary, a holy place (Lindahi-Öhrling, 1780) as well as “passe “holy”; passe-ware, “holy mountain” (Friis, 1887)” (cited in Whitaker 1957: 297).

Similar structures are evident in other rock art landscapes as well as on Sámi noaidi drums from the seventeenth century. Some drums have a clear pole-like structure representative of the axis-mundi, whilst segmental type drums show the content divided into different zones. From within Sámi scholarship. Attempting to better understand the arrangement and composition of the noaidi, Sámi scholar Louise Bäckman (2005: 29), notes the following:

“Due to individual personality, a noaidi was able to renew Sámi mythology but did not change the fundamental structure of the belief system or religious ideas. […] Noaidi preserved and effectively transmitted the traditional myths and were also able to renew old myths as well as create new ones”.

The painted landscape above (Figure 1) includes what could be animal souls that are dancing and what appear to be animated spirit figures with triangular heads if viewed within a Sámi context. They are animated because of their large size and elevated position in contrast to the animal soul-figures who are dancing. It is well known in Sámi shamanism that the spiritual helpers summoned by noaidi were in some instances invisible. This could explain why these figures appear to be dancing because they are portrayed as souls. The view of triangular-headed figures at the Hossa site as spirits is supported by their extensive occurrence on Sámi drums and at other rock art sites in Finland, and therefore, their designs could be identity markers. The human-like figures and animals are all dancing. However, it is difficult to assess if these illustrations have been painted by one or more noaidi.

In addition, Sámi scholar Elina Helander (2004: 555) states that:

“Shamanism is a very central cultural-ecological factor among northern peoples. Sámi shamanism relates to the myths of the Sámi people. The inner world and thoughts of a shaman find expressive voice through songs, drum symbols, and (descriptions of) their rituals, activities, experiences, and dreams”.

A close observation of the location of the human-like figure with horns of oversized ears reveals that it was not painted on a flat surface but on a fissure in the rock. This feature of the painting could represent a sacred door connected to a sacrificial cave where, symbolically, offerings are placed[5]. In addition, elk and deer figures are also painted on this fissure, as examples of animal souls that, after being offered to the spirits, became the noaidi’s helpers. The fissure in the rock might represent the border that separates the invisible side of the middle world from the mythical Sáivo world, which on some Sámi drums is below the earthly realm. Additional evidence is the human figure with an outstretched arm over the other side of the fissure, below the dancing wolf-like figure. On some Sámi drums, the middle world and Sáivo world or world of the dead Jabma Aimo are separated by a zone or borderline area.

Conversely:

“The dead were thought to continue their lives in an underworld called Saivo, like our own world only better. The Saivo-concept was linked with lakes and mountains, which thus, acquired some religious prestige, and were respected and worshipped.” (Whitaker 1957: 296).

Regarding descriptions of the Sámi view of the world depicted within Sámi pre-Christian religion:

“A general feature of the Sámi religion, as noted by Louise Bäckman, professor of Comparative Religion and a Southern Sámi herself, is that all living beings, humans and animals, have at least two souls. One of the souls, the bodily soul, is closely connected with the physical body. The other soul is the free soul that can leave the physical body, transform into a different shape and form and travel long distances. Animals too have a bodily soul and a soul that can leave the body. The noaidi is able to separate the free soul from the physical body and as a result, go on long journeys to collect knowledge. (Solbakk 2018: 16-17).

Another point of interest is what looks like the body of a large reindeer or elk, which is also included on many Sámi drums on the northern axis. Its size and position raise additional questions.

The creation of rock art in relation to Sámi cosmology

Placing prehistoric rock art in a specific cultural context requires interpretation, which scholars in Finland have warned against because it is considered there was no Sámi culture before the end of the last millennium BCE[6]. Typically, scholars have placed the origins of the rock paintings within the North Eurasian Hunting cultures which no longer exist. These views obscure the importance of placing priority on rock art as integral to local cultural traditions, of the Sámi.

As research into the history and culture of the Sámi people has developed and more rock art sites have been discovered in Finland, it is important to consider what Sámi linguist Ante Aikio states in relation to Sámi history and culture. While theories of rock art being connected to earlier North Eurasian hunting cultures are valid, so are theories linking them with different Sámi groups who lived in different areas but who would have travelled extensively following the reindeer and transmitting their cultural heritage through art over a very long period. To not give this equal consideration in rock art research risks marginalising the Sámi and their history. According to Aikio (2012: 106)

“While Saami languages can be shown to have come to Lapland from the south, the Saami as an ethnic group did not “come” from anywhere-they were formed in their present territories through a complex social process that involved the adaptation of a new language. The earlier speakers of “paleo-Laplandic” languages belong to the cultural and genetic ancestors of the Saami even if they were not their linguistic ancestors”.

Furthermore, Sámi historian Veli-Pekka Lehtola (2002: 21), makes two important points in relation to this. The first is that “archaeologists have shown that northern Fennoscandia became predominantly Sámi in the first millennium BC”. And secondly, “Sámi heritage of pictorial art reaches back to the rock drawings of thousands of years ago” (Lehtola 2002: 116). A question arises as to whether the Sámi from the “first millennium BC” Lehtola (2002: 116), understood, developed and maintained their spiritual culture which they inherited from their “[…] genetic ancestors” Aikio (2012: 106). Accordingly, the spiritual aspects of this culture in addition to hunting, fishing and trapping were transmitted through cultural landscapes recorded in art. This may well explain why there are so many analogies between sacred Sámi drum landscapes and prehistoric rock art in different locations throughout Fennoscandia.

What is more, according to Sámi archaeologist Inga-Maria Mulk and Tim Bayliss-Smith (2013: 2).

“Rock art in Fenno-Scandinavia can be divided into northern ‘hunter art’ and southern ‘farmer art’ styles. The distribution of rock art sites shows that ‘hunter art’ is found not only in the area where the Sámi people live today but also across a much more extensive area settled in former times by the ancestors of the Sámi […]”.

With additional reference to what is stated above, Finnish archaeologist Antti Lahelma has noted how:

“Perhaps the single strongest argument that associates the art with shamanism of the kind practice[d] by the Saami are scenes that depict falling, diving, and shape-changing anthropomorphs. The falling humans are usually accompanied by an elk, fish, or a snake … these scenes are an almost perfect match with Saami shamanism, (Lahelma 2008a: 52)”.

Also, in relation to Sweden and Norway, scholars Ernst Manker and Ørnulv Vorren noted in the 1960s how “on the Lapp magic drums, there are all the animal forms found in rock carvings; elk, reindeer, bear, etc […].” (Manker and Vorren 1962: 95). The same might be said also for rock paintings.

Some of the most compelling evidence of links between the distant ancestors of the present-day Sámi and the creation of rock art can be found in Inga-Maria Mulk and Tim Bayliss-Smith’s “Sámi Rock Engravings from the Mountains in Laponia, Northern Sweden” (1999)[7]. A later publication by the same authors: “Rock Art and Sami Sacred Geography in Badjelánnda, Laponia, Sweden. Sailing Boats, Anthropomorphs and Reindeer” (2006), presents a more detailed study of the site. According to Mulk and Bayliss Smith (1999: 96), “the evidence available […] does at least suggest that the rock engravings of boats at the Padjelantá date from during, or just after, the Viking period, c. 800-1300”, which suggests the creation of rock art long after the prehistorical period ended.

Sámi shamanism, mythical landscapes, and rituals at the Hossa site

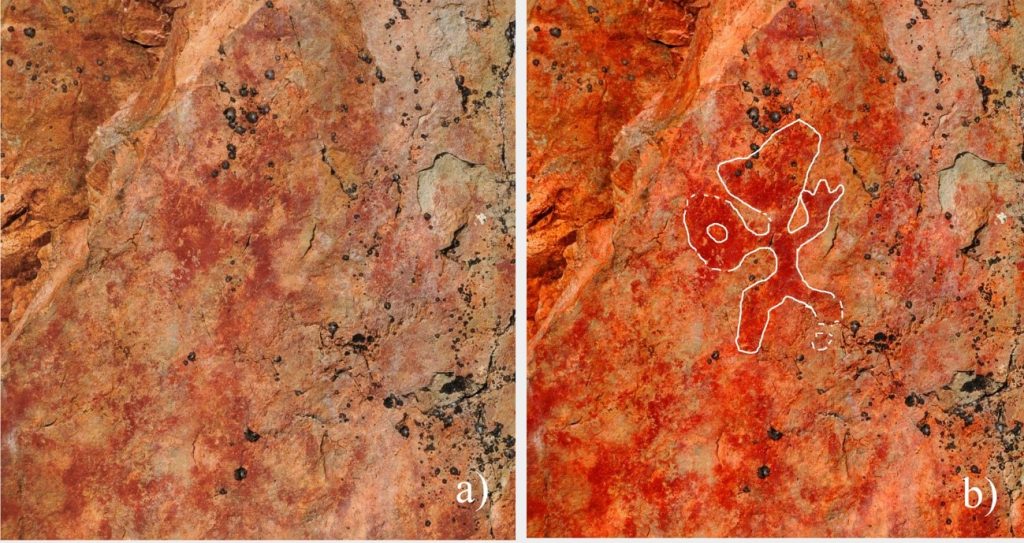

Figure 2. The central area of the rock on the panel at the Hossa site is dominated by this dancing figure with facial features that resemble a wolf-like persona who is interacting with other animals. Photograph and copyright Francis Joy (2005).

The figure which may have metamorphosized into its current form has been painted using red ochre and has its arms outspread. There appears to be a tail between its legs as well as an erect penis which could be interpreted as one of the side effects of ecstasy. What resembles ear or horn-like features on the figure’s head could suggest a representation of the soul of the shaman who has transformed into an animal and, thus, placing him among other animal souls because of the transition from the human form. A closer examination of the facial features indicates that the eyes and nose of the figure were carefully designed in connection to the underlying rock surface The markings appear to be in the stone rather than the paint.

The panel reveals connections to the Sámi view of the world and related rituals, beliefs, and practices from the seventeenth century. A study of these may bring about a more comprehensive understanding of the site. A painted human figure with a head, back, legs and right arm appears just below the central dancing figure on the panel.

Figure 3. A human figure is visible directly below the wolf-like figure who is dancing. Photograph and copyright Francis Joy (2005).

If the fissure in the rock face acted as both a holy doorway to a sacrificial cave and a dividing line between the physical world and the Sáivo realm, then the dancing wolf-like figure and the human figure who is also dancing or ascending from below might be:

“[…] Noaidegázzi [who] could be perceived as deceased relatives or noaidi who lived in the Sáiva/Bassevárri (the Sámi “Paradise” […]) and whom it was believed could help when the siida people in distress. To get in touch with them in Sáivu, the noaidi had these invisible helpers at his disposal: the mentioned bird – noaideloddi, a fish – noaideguolle, or a reindeer buck – noaidesarvvis (further south called saivoloddi, saivoguolli and sáivosarvvis). In addition, a snake: gearpmaš. These were also collectively called noaiddesvuoigna – noaidi spirits” (Solbakk 2018: 18-19).

Solbakk’s description is helpful because, given the location of the rock painting site just above the lake surface, the water acts as a membrane between the physical world and realms below the water, namely, the mythical Sáivo world and world of the dead Jabma Aimo. These dividing lines on Sámi drum landscapes similarly indicate how the landscape has been perceived and utilized for spiritual purposes. In addition to this, noaidi also sacrificed animals to deceased relatives, some of whom may have been noaidi, for their help and protection.

A further contribution from Rafael Karsten (1955: 56), notes how: “the Lapps […] had quite realistic ideas about the Aimo-people. They were supposed to lead about the same life in Hades as those living on the earth, who take great interest in the destiny of their departed relatives.”

What is more, Karsten (1955: 111-112) states:

“Again, Solander remarks that the Lapps believe they can awaken some of the dead so that they may protect their reindeer against wild beasts[8]. […] The tutelary spirits, which according to the belief that Lapps inhabit mountains and lakes and bear in common the name Saivo, were spirits of the departed and especially spirits or souls of shamans.”

The second point of interest concerns what looks like a large deer or elk. Given its location, the figure might be a symbol connected to a constellation over the northern skies which could suggest an astral mythology in which “the whole body of the animal is on the Milky Way in the midst of the group of stars mentioned in the Greek myth of Perseus” (Pentikäinen 1998: 73).

Figure 4. A close-up of the deer or elk figure at the top of the panel. Photograph and copyright Francis Joy (2005).

The large animal’s link to the constellation is due to its size and location in comparison to the size of other deer and elk figures lower down on the painted panel. These could be representative of the middle world or physical reality. What we see as figures dancing below a large reindeer or elk would correspond with this. In earlier research (2007), I connected the deer or reindeer to both Siberian and northern culture. However, my re-evaluation attempts to link the figure with Sámi cosmology considering that seventeenth-century drums feature reindeer on the upper part of many drums thus connecting the animal to the sky above the northern universe[9].

Recent images of Sámi drums and stories within Sámi myths are predominantly linked to the seventeenth century. If the large deer image at Hossa is indeed a representation of the constellation over the northern sky, we see an ancient belief system that spans thousands of years across cultures and peoples linked to Sámi mythology. If the Hossa site is a cosmological representation of a sacred rock formation, then it is equally plausible to suggest that from such a vantage point one would, likewise, be able to observe the northern sky.

According to Swedish scholar Bo Sommarström in relation to the Sámi noaidi and the significance of the reindeer bull painted on cosmological drum landscapes:

“As Sarves, reindeer bull, it serves as one of the principal power or guardian spirits of the shaman, sometimes even as his alter ego. When he entered another state of consciousness with the help of drumming, his reindeer vision must have looked as real as in ordinary life” (Sommarström 1987: 247).

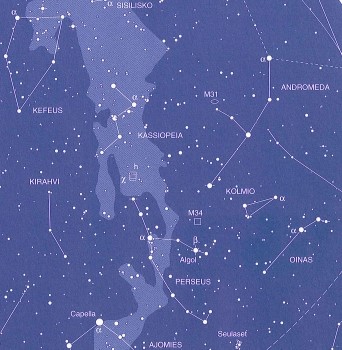

Figure 5. A star map of the northern skies.

“A star map showing the location of Cassiopeia and Perseus in the northern sky within the circumpolar region of the world, ‘Länsi’ – west, which is on the right side. (Helsingissä Tähtitieteellinen Yhdistys Ursa 1998, 23)” (Joy 2016a: 228). “Cassiopeia, Perseus, and the Waggoner, among others, belong to the Elk constellation, in Sámi called Sarvva” (Helander-Renvall 2005, 10)”. Furthermore, “in Sámi myths, one of the names given to these constellations is Sturra Sarvva” (Joy 2016a: 227).

The image of the large deer or elk at Hossa is also presented in the work of Finnish artist Antero Kare who argues that the image appears as one of the largest animals on the panel, thus, indicating further possibilities that it is a mythical being. In addition, Helen Taskinen mentions a headless elk figure in her study (1999). However, the one pictured above is higher up and by contrast, it is not like a stick figure, as is depicted in Taskinen’s booklet (p.4 & 6), because its body has been filled with red ochre and it is directly above where the wolf-like figure and other animals are dancing.

Parallels between Hossa figures and those on Sámi drums from the seventeenth century

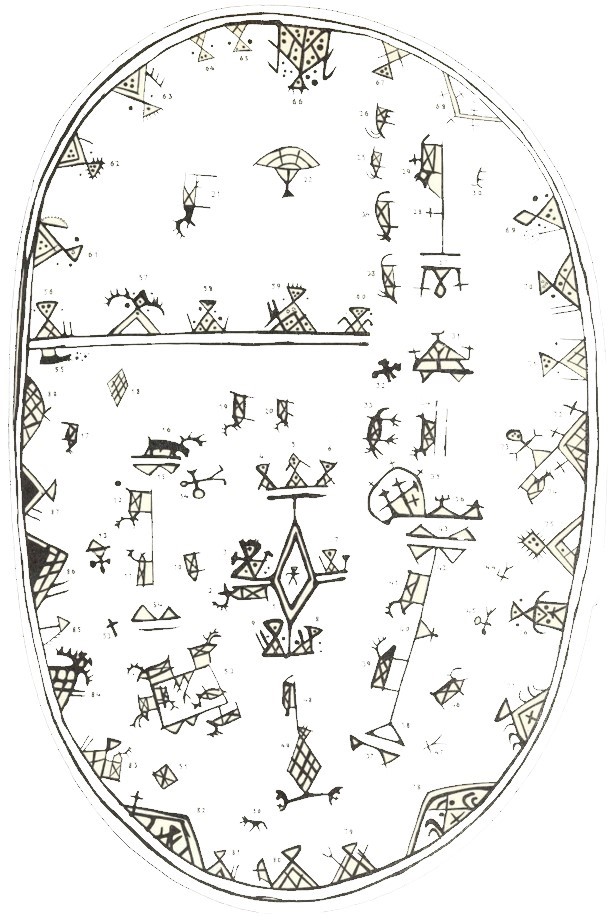

Figure 6. Drum number 27 which is of the Åsele type from Swedish Sápmi, from Ernst Manker (1950: 299).

Figure 6. Drum number 27 which is of the Åsele type from Swedish Sápmi, from Ernst Manker (1950: 299).

On the central axis of the south Sámi drum at the top of the northern sun ray is one of many examples illustrated on different drums of a reindeer, which is a symbol of the celestial being over the northern skies. We can see a connection between the position of the animal on the drum and that painted high up on the Hossa panel. Like the Hossa panel, it is worth noting how there are very few south Sámi drums where the landscapes are divided into different tiered zones, unlike those on the northern and Kemi Sámi drums[10].

The cosmological landscapes on the southern Sámi drum designs are: “characterized by a central sun cross (missing on a single drum) and an unbroken path around the edge, and by the absence of horizontal lines separating the field in separate compartments as in all other styles”. (Kristiansen 2011: 1).

The cosmological features of the Hossa site are not necessarily as clearly defined as they are on drums. The artist or artists at the Hossa panel may have perceived the landscape as a sacred representation of rock formation, such as a mountain or cliff, with the prominent feature of the large stone face to the left of the painting inhabiting this abode. The artist would have recognized the relationship to the drums used for divination as the spirits directed the way the ARPA (divination tool) moved on the drumhead when struck. When we consider how sieidi or sacred places are illustrated on many Sámi drums, some with facial features and located by water, it is possible to recognize additional links to the Hossa site.

Figure 7. The noaidi’s most important tool was the drum, which was used to undertake out-of-body journeys into the spiritual world. In addition, spiritual assistants were the souls of animals and deceased ancestors. Photograph and copyright Rainio et al (2014).

The most recent discovery at the Hossa site by Rainio and colleagues is a human figure holding a drum. However, it is very difficult to make a solid interpretation of this because of the way the colour has run or been smudged on the surface of the rock due to erosion. On the other hand, identifying a drummer depicted on what could be a mountainous landscape or cliff could provide a new understanding as to why some of the figures on the panel are dancing. Moreover, linking them to states of trance and ecstasy is important because these states of consciousness are primarily induced by drumming in shamanic traditions.

In reference to the figure holding a drum Rainio et al (2014) used archeoacoustic research at the Hossa site to determine the following:

“Some ethnographic sources indicate that Sámi noaidi or shamans of the historical period sang or chanted at places that featured a prominent echo (Paulaharju 1932: 50), and while drumming is not mentioned, it seems reasonable to assume that a shaman drum (goabdes), could also be used in such a context, as shamanism and the use of drums are strongly connected in both Sámi culture and more generally in the circumpolar Arctic (e.g. Ahlbäck and Bergman 1991). This makes it particularly interesting to note that during our fieldwork, we identified a probable depiction of a drummer […] overlooked in the previous documentation work carried out at Värikallio (Taavitsainen 1979; Kivikäs 1995, 87-101)” (Rainio et al 2014: 149-150).

Conversely, dancing is not depicted on seventeenth-century Sámi drums, but flying which is associated with trance and ecstasy is as noaidi figures holding drums.

The content of the painted panel at Hossa does not suggest a hunting scene. It appears to be linked to a ritual of some kind. As far back as shamanic practices have been documented, dancing has been a central feature in a multitude of different ceremonies, rituals and contexts. Thus, shamans used dance to alter consciousness as a way of merging with supernatural powers, as evident in the Sámi noaidi.

Figure 8. The two triangular-headed stick figures are reminiscent of those depicted on different Sámi drums from the seventeenth century. Photograph and copyright Francis Joy (2005).

From an overall assessment of the images presented in Antero Kare’s research (2000), it is possible to count five stick-like figures with triangular heads at the Hossa site. One of these appears to have horns. By comparison to the size of the other animal and human figures in proximity, these are clearly much larger suggesting they could be spirit beings.

We find on numerous Sámi drums from the seventeenth century multiple figures with triangular heads, some of which have horns that are depicted as spirits, or in connection with sacred offering places on hills, cliffs and mountains. This particular dimension of Sámi pre-Christian religion is a subject matter written extensively about in my earlier published works (2017 and 2018).

From this research, it has been possible to ascertain how:

“[…] There are paintings that feature figures with triangular shaped heads at Uittamonsalmi, Ristiina; close to the Astuvansalmi rock paintings, Haukkalahdenvuori I, Enonkoski; Vierunvuori in the municipality of Heinävesi; also, Humalniemi, Heinävesi; Kolmiköytisienvuori, Ruokalahti; Pyhänpää, Kuhmoinen; Ruominkapia, Lemi; Hahlavuori, Hirvensalmi; Uittovuori, Laukaa; Kalamaniemi II, Luumäki; Saraakallio I, Jyväskylä and Halsvuori, Jyväskylä.” (Joy 2017: 19).

Further evidence of the parallels between the figures at the Hossa site and those depicted on seventeenth-century drums include a wide variety of triangular-headed spirit figures, some of which only have one eye, for instance, on the central axis of the drum. Also evident are triangular-headed figures with two eyes. These, likewise, correspond with the triangular-headed figure seen in the lower part of the picture in figure 10 (below).

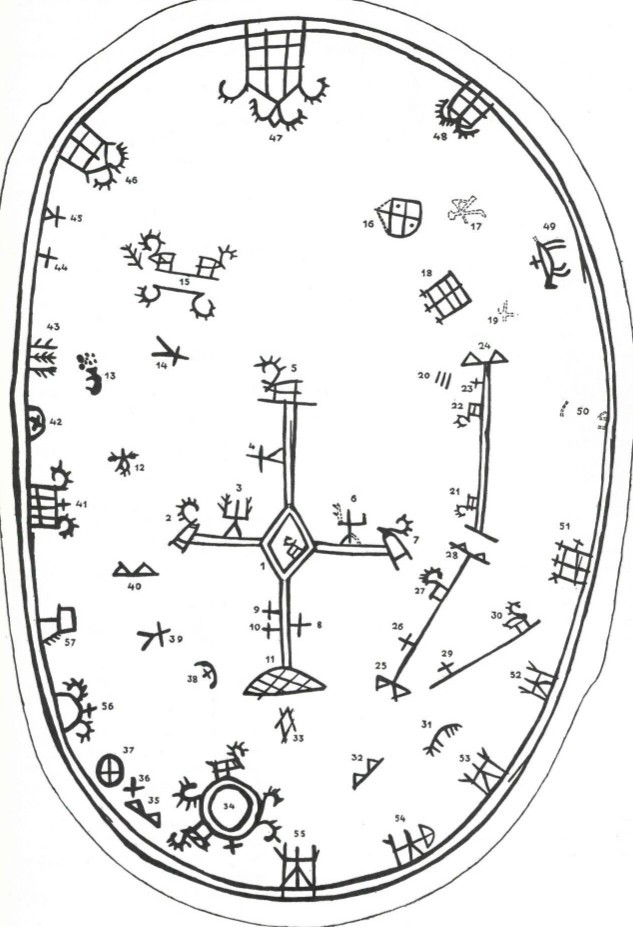

Figure 9. Drum number 17 from Luleå, Swedish Sápmi, from Manker (1950: 270).

Equally as important to recognize in this landscape are two noaidi figures holding circular objects that can be interpreted as drums. These are to the left of the central axis in the middle of the drum and in the lower field on the right side. One is sideways and the second is upside down, which is an indicator they are flying. Both (triangular-headed figures and noaidi figures) correspond to the content of the Hossa panel and, therefore, deserve to be noted because they facilitate a broader understanding of the factors leading to the artwork’s creation.

Those figures that clearly have faces painted on them evoke some anthropomorphic sieidi sites in Finland where stone faces are visible within rock formations. Eyes in particular are visible and therefore indicate critical links between sieidi sites, rock art and drum landscapes. Typically, sieidi illustrated within drum landscapes are not seen in such detail as those on the drum from Luleå, Swedish Sápmi, in terms of facial features. Other Sámi drums feature stick figure designs only. The owner of the drum (figure 9) has made a distinction between triangular-headed figures with facial features and those that do not. This is essential to recognize because it supports a case for links to Sámi cosmology in different contexts.

Figure 10. The bottom or lower section of the painted panel at Hossa is just above the waterline of Lake Somerjärvi. Photograph and copyright Francis Joy (2005).

Regarding another association between the figures on drums and those at the Hossa site, in figure 10 there is a human figure just above the triangular-headed figure as well as a fish-like figure that looks like it has human characteristics. Both emerge vertically from the base of the boulder. Other markings directly above this figure look anthropomorphic. Watching over them is a triangular-headed figure with one eye. The head is like those of the pair higher above on the panel presented in figures 8 and 9. A question remains here about the significance of the water as a membrane through which is the realm of Jabma Aimo, the world of the dead, or the Sáivo world?

On the above Sámi drum from “Luleå, Swedish Sápmi” (Manker 1950: 270), there is a multitude of spirit figures in different realms within the cosmological landscape that have only one eye, and another that has two eyes, which are almost identical to the ones painted on the Hossa panel. This suggests further associations between these landscapes and links to Sámi culture.

In terms of the fish-like figure depicted in figure 10, according to Louise Bäckman (1975: 144), “the Lapp noajdie summoned his theriomorphic beings from sáivo-ájmo, the abode of the spirits […] [including] the fish sájvo-guölie, to accompany his free soul to worldly or extra worldly places”. The pertinence of Bäckman’s assertion is establish because the Hossa site is so old. In terms of the resurrection of the dead or the transmigration of souls, the surface of the water is representative of a membrane that separates the physical and spiritual worlds.

In contrast to other triangular-headed figures, this one is below the other figures higher up the cosmological sacred mountain or cliff. This might indicate that, like the figures on the drums, they can be illustrated in different places and so can be moved around in relation to the nature of the narrative being depicted. These activities and portrayals are consistent with the Sámi view of the world and cyclical universe.

The scaffolding of tradition and cosmology in the creation of epic landscapes

The depiction of Sámi spiritual traditions in sacred art reveals the construction of cosmology in different contexts. Through symbolism and figures, for example, these designs could be linked to identity and have been preserved within both prehistoric rock art and painted drum landscapes from the seventeenth century. The Hossa panel could be depicting a knowledge system that has between 3-4 tiers in a similar way to how some Sámi drum landscapes include zones.

The question arises as to whether drum landscapes evolved from rock painting landscapes. As indicated in the prehistoric rock art of Alta, Finnmark, Norway, drums from prehistory feature scenes of dancing as is the case at the Hossa site. Drum landscapes that have survived from the seventeenth century suggest the long-term survival of traditions, beliefs, and practices from prehistory. Moreover, communication using drums demonstrates cooperation between different dimensions whereby the landscape is seen as a living entity.

The drum landscapes exhibit deep ties to other drums as well as rock art, thus, exhibiting connections between distant and recent ancestors in the spirit world. This includes animal relatives and assistants-helpers. Both rock art and drum landscapes exhibit the cyclical and reciprocal nature of the universe and its cycles and who-what are noaidi, spirits, animals, ancestors, and sacred places. All these elements and structures are intricately tied with local beliefs and practices.

When we consider the size of the dancing wolf-like figure, human figure, and triangular-headed figures, we see a distinct difference in size. One possible explanation for this is during ritual dances and:

“[…] Altered state experiences in the trance dance [a shaman] […] may feel either very small or engage with big animals. It is […] [possible] that the different sizes and placement of motifs seek to recreate for the viewer the experiences of the painter.” (Loubser 2013: 34).

This might help explain these variations in proportion.

Archaeologist Antti Lahelma conducted fieldwork at the Valkeisaari rock painting in south-east Finland where a large stone anthropomorphic head and face are visible at the site. Lahelma (2006: 15), draws on parallels with “[…] the Saami cult of the sieidi – sacred cliffs and rocks viewed as a living, breathing ‘other-than-human persons’ (Lahelma 2008b) Lahelma also goes on to say how in 2008: “seven Finnish rock paintings are similarly located on such boulders, often identical in terms of shape, size, and location. […] Cliffs such as these are not particularly common locations for sieidi, but some do exist.” (Lahelma 2008b: 129).

In contrast to the offerings-deposits found at the Valkeisaari rock painting which present evidence of worship or reverence to the sieidi, no offerings or deposits have been found at the Hossa site. It remains unclear what kind of offerings may have been made or again, if at all, a particular type of worship may have taken place at this large face in the boulder formation. However, not all sieidi sites may have been linked with or identified solely with offerings. For example, in terms of dancing:

“It has been suggested that all three words – Saami sieidi, Saami siida, and Finnish hiisi – are derivatives of a root šej (hei) meaning movement or dancing (cf. Finnish heilua ‘to sway’, heijua ‘to rock’, heittää ‘to throw’, heipata ‘to sway’, hiipottaa ‘to tiptoe’). In this case, the original meaning of the word sieidi would have been ‘object of, or a place for, a ritual dance.” (Koponen 2005: 392).

In a broader context a place such as Hossa would have meaning in the sense that a mountain or cliff can be a sieidi which is what makes it sacred. It is a place where different souls meet.

Concluding remarks

The aims of this article were to reevaluate the prehistoric Hossa Värikallio site in terms of Sámi shamanism and cosmology from the seventeenth century.

A significant difference between rock art landscapes in Finland from those depicted on seventeenth-century Sámi drums is that there are rock painting sites in Finland where human figures and animals are dancing. By contrast, there are no dancing human or animal figures depicted on Sámi drums that have survived. Dancing would have been forbidden by missionaries and, therefore, viewed as ungodly. Evident in rock paintings and on drums, however, are ritual postures and out-of-body-traveling. Each of these practices is commonplace within shamanism. In addition to this, like painted drum landscapes, a rock art panel that includes a mountain or cliff-like structure may also depict the tiered structure of a mythical landscape. This assertion matches what Antti Lahelma (2007: 123) refers to as:

“[…] The role of noaidi (‘shaman’) as the mediator between the world of humans and spirits, and the notion that certain rocks, cliffs or mountains are sacred and inhabited by the spirit helper beings of the noaidi. The noaidi used a drum to reach trance, in which his free soul would journey to the world below, often in the shape of a zoomorphic spirit helper (noaidi gadze). By visiting the holy mountains and cliffs, the noaidi could access the power of the supernatural snake, fish, bird or wild reindeer (Bäckman 1975, Pentikäinen 1995)”.

In terms of a drum landscape, all the elements are contained within the oval shape of the drums that replicate the tiered Sámi cosmos. The Hossa Värikallio rock painting is one such place where these elements contained with a mountain or cliff-like landscape by a lake spread out over a wide, encompassing area. Accordingly, “the replication of the macrocosm in the microcosm can also be seen at painted [rock art] sites” (Loubser 2013: 31); as well as on some Sámi drums.

On the Hossa panel, human-animal interactions express shamanistic values. Human-animal encounters are examples of more than human ethnographies whereby animals and spirits feature prominently in narratives as bearers of traditions. This is of course evident in the shaman who changes into an animal through dancing which is apparent at the Hossa site, or who flies like a bird as is evident on Sámi drums. Likewise, both animals and spirits play a role in sacrificial rituals and offering practices.

If rock art panels such as those at Hossa are linked to shamanism and cosmology, then old drum landscapes offer maps to remembering interactions with spiritual powers from different realms. It may also be the case that the paintings express the working relationship between the noaidi and supernatural powers. The art may have been orchestrated by them and thus we see common patterns between the Hossa figures and those on the sacred drum landscapes.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to Oula Näkkäläjärvi for his assistance in making this new research possible, to John Ryan for proofreading the paper, in gratitude for the memory of Alpo Rissanen.

References

Ahlback, T. and Bergman, J. (eds). (1991). The Saami Shaman Drum. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell.

Aikio, A. (2012). An Essay on Saami Ethnolinguistic Prehistory. In Riho Grünthal and Petri Kallio (eds) A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe. Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 266, pp. 63–117.

Bäckman, L. (1984 [1975]). Sájva: Föreställningar om Hjälp- och Skyddsväsen I Heliga Fjäll Bland Samerna. [Sájva: Conceptions of Guardian Spirits Among the Lapps]: Almqvist & Wiksell international, Stockholm, Sweden.

Bäckman, L. (2005). “The Noaidi and his Worldview: A Study of Saami Shamanism from an Historical Point of View”. In: SHAMAN – The International Journal for Shamanistic Research (ISSR), Volume 13. Nos 1-2. Spring/Autumn 2005, pp. 29-40.

Coddington, J. (2014). A Basis for Comparison: The Thomas Walther collection as Research Collection. In: Mitra Abbaspour, Lee Ann Daffner, and Maria Morris Hambourg, eds. Object: Photo. Modern Photographs: The Thomas Walther Collection 1909–1949. An Online Project of The Museum of Modern Art. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. http://www.moma.org/interactives/objectphoto/assets/essays/Coddington.pdf

Cox, J, L. (2007). From Primitive to Indigenous: The Academic Study of Indigenous Religions. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Friis J, K, (1887). Ordbog Over Det Lappiske Sprog. Christiania.

Gjerde, J-M. (2021). Rock Art and Landscapes: Studies of Stone Age Rock Art from Northern Fennoscandia. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Tromsø, Norway.

Helander. E. (2004). “Myths, Shamans, and Epistemologies from an Indigenous Vantage Point”. In. Snowscapes, Dreamscapes. Snowchange Book on Community Voices of Change, eds. E. Helander & T. Mustonen: Fram Oy, Vaasa, Finland, pp. 552-562.

Helander-Renvall, E. (2005). Silde: Sámi Mythic Texts and Stories: Kalevaprint Oy, Finland.

Helsingissä Tähtitieteellinen Yhdistys Ursa. (1998). Ursan Tähtikartasto: Joka kodin Tähtikartasto, [Ursa Star Atlas for Every Home]. Ursan Julkaisuja 68: Painopaikka Ykkös-Offset, Vaasa.

Joy, Francis. (2014). “To All Our Relations: Evidence of Sámi Involvement in the Creation of Rock Paintings in Finland”. Polar Record / First View Article: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-4.

Joy, Francis. (2016a). The Sámi Noaidi Grave in Kuusamo and the Significance of the North-South Orientation. Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 19, Number 1, pp. 208-243.

Joy, Francis. (2016b). “The Vitträsk Rock Painting and the Theory of a Sámi Cosmological Landscape”. Suomen Antropologi Issue 3, Volume 41: pp. 44-68. https://journal.fi/suomenantropologi/article/view/60389.

Joy, Francis. (2017) “Noaidi Drums from Sápmi, Rock Paintings in Finland and Sámi Cultural Heritage, An Investigation”. First View Article / Polar Record: A Journal of Arctic and Antarctic Research, Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0032247416000917, pp. 1-20.

Joy, Francis. (2018). Sámi Shamanism, Cosmology and Art as Systems of Embedded Knowledge. Doctoral Dissertation: Acta Universitatis Lapponiensis 367. The University of Lapland. URL: http://lauda.ulapland.fi/handle/10024/63178

Kare, A. (2000). “Rock Paintings in Finland”, in, MYANNDASH Rock Art in the Ancient Arctic, ed. A. Kare: Published by the Arctic Centre Foundation, Rovaniemi, Finland, pp. 88-127.

Karsten, R. (1955). The Religion of the Samek. Ancient Beliefs and Cults of the Scandinavian and Finnish Lapps: E. J. Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Kivikäs, P. (1995). Kalliomaalaukset – Muinainen Kuva Arkisto. Jyväskylä: Atena.

Kivikäs, P. (1997). Kalliomaalausten Kuvamaailma. [Rock Paintings and Picture of the World]: Gummerus OY: N Kirjapainossa, Jyväskylässä.

Kivikäs, P. (2001). Rock Paintings in Finland. In: Mare Koiva, Andreas Kuperjanov, Väino Poikalainen and Enn Ernits (eds). Estonian Journal of Folklore, Volumes 18 and 19. Published by the Folk belief and Media Group of ELM, pp. 136-161Available at: https://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol18/finland.pdf

Kivikäs, P. (2009). Suomen Kalliomaalausten Merkit: Kalliot, Kuvakentät Ja Kuva-Merkitykset. Atena, Jyväskylä, Finland.

Koponen, E. (2005). “Sieidi”, in, The Saami. A Cultural Encyclopaedia, eds. E. M. Kulonen., I. Seurujärvi-Kari., & R. Pulkkinen: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. SKS. Helsinki, pp. 392.

Kristiansen. R. E. (2011). Sami Drum. http://old.no/samidrum

Lahelma, A. (2005). “Between the Worlds. Rock Art, Landscape and Shamanism in Subneolithic Finland”. Norwegian Archaeological Review 38(1), pp. 29–47.

Lahelma, A. (2006). “Excavating Art: A Ritual Deposit Associated with the Rock Painting of Valkeisaari, Eastern Finland”. Fennoscandia Archaeologica XXII, pp. 3-32. http://www.sarks.fi/fa/PDF/FA23_3.pdf

Lahelma, A. (2007). On the Back of a Blue Elk: Recent Ethnohistorical Sources and Ambiguous Stone Age Rock Art at Pyhänpää, Central Finland. Norwegian Archaeological Review, Volume 40, No. 2. Published by Taylor Francis, pp. 113-137. DOI: 10.1080/00293650701708875

Lahelma, A. (2008a). A Touch of Red: Archaeological and Ethnographic Approaches to Interpreting Finnish Rock Paintings: Helsinki: Finnish Antiquarian Society.

Lahelma, A. (2008b) “Communicating with Stone Persons – Anthropomorphism, Saami Religion and Finnish Rock Art”. Paper III. Julkaisussa. A Touch of Red: Archaeological and Ethnographic Approaches to Interpreting Finnish Rock Paintings: Iskos 15. Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys ry, pp. 121–142.

Lahelma, A. (2012). “Kuka Maalasi Kalliot? [Who Painted the Rocks?]”, Muinaistutkija 1/2012, pp. 2–22.

Layton, R. (2012). “Rock Art, Identity and Indigeneity”, in, Companion to Rock Art, First Edition, ed. J McDonald and P Veth: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, pp. 437-454.

Lehtola, V-P. 2002. The Sámi. Traditions in Transition. Kustannus-Puntsi Aanaar – Inari, Finland.

Lindahl, E., and Öhrling, J. (1780.) Lexicon Lapponicum. Holmiae.

Loubser, J. (2013). “A Holistic and Comparative Approach to Rock Art”, in, Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture, Volume 6 – Issue 1, pp. 29-36. https://doi.org/10.2752/175169713X13500468476448

Luho, V. (1971). ”Suomen Kalliomaalaukset ja Lappalaiset. [Finnish Rock Paintings and the Lapps]”. Kalevalanseuran Vuosikirja 51, pp. 5–17.

Luukkonen, I. (1994–2023). ”Suomen Kalliomaalaukset [Rock Art in Finland]”. http://www.ismoluukkonen.net/kalliotaide/suomi/

Luukkonen, I. (2021). Suomen Ensihistorialliset Kalliomaalaukset. Oy Sigillum AB, Turku.

Manker, E. M. (1950). Die Lappische Zaubertrommel: Eine Ethnologische Monographie. 2. Die Trommel als Urkunde Geistigen Lebens [The Lappish Drum: An Ethnological Monograph. 2. The Drum as a Record of Spiritual Life]: Stockholm, Sweden: H. Gebers.

Manker, E. M. and Vorren, Ø. (1962). Lapp Life and Customs. A Survey. Translated from the Norwegian by Kathleen McFarlane: Published by Oxford University Press, London.

Moen, T. 2(006). Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methodology 3 (4), Article 5. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/160940690600500405

Mulk, I. M. and Bayliss-Smith, T. (1999). Sámi Rock Engravings from the Mountains in Laponia, Northern Sweden, in: Kõiva, Mare & Kuperjanov, Andres (eds.). Estonian Journal of Folklore Volume 11. Published by: FB and Media Group of Estonian Literary Museum https://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol11/sami.htm

Mulk, I. M. and Bayliss-Smith, T. (2006). Rock art and Sami Sacred Geography in Badjelánnda, Laponia, Sweden: Sailing Boats, Anthropomorphs, and Reindeer: Umeå Universitet. Arkeologiska Institutionen, Sweden. University of Archaeology and Sami Studies.

Mulk, I-M. (2013). Máttaráhkká: Mother Earth in Sami Rock Art. Past Horizons – Adventures in Archaeology. URL: http://www.pasthorizonspr.com/index.php/archives/03/2013/mattarahkka-mother-earth-in-sami-rock-art Accessed on 15.03.2014.

Niskanen, K. 2(017). Prehistoric Pictographs in Finland: Symbolism and Territoriality. Quarterly International. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2017.10.030

Núñez, M. (1995). “Reflections on Finnish Rock Art and Ethnohistorical Data”. Fennoscandia Archaeologica 12, pp. 123–135.

Paulaharju, S. (1932). Seitoja ja Seidan Palvontaa.Helsinki: Suomalainen Kirjallisuuden Seura.

Pekkonen, O. (1999). Raising a Storm. Books from Finland Volume XXXIII, No. 1. Published by Helsinki University Library.

Pentikäinen, J. (1987). “The Shamanic Drum as Cognitive Map”, in, Mythology and Cosmic Order, eds. R. Gothóni & J. Pentikäinen: Studia Fennica. Review of Finnish Linguistics and Ethnology 32. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Helsinki, pp. 17–36.

Pentikäinen, J. (1995). Saamelaiset. Pohjoisen Kansan Mythologia. Karisto, Hämeenlinna.

Pentikäinen, J. (1998). Shamanism and Culture. Etnika Co. Gummerus Publishing, Jyväskylä.

Rainio, R., Äikäs, T., Lahelma, A., Okkonen, J., & Lassfolk, K. (2014). Acoustic Measurements at the Rock Painting of Värikallio, Northern Finland. In: Eneix, Linda, C. (ed). Archaeoacoustics: The Archaeology of Sound. Publication of Proceedings from the 2014 Conference in Malta. Published by the OTS Foundation, pp. 141-152.

Reuterskiöld, E. (1910). Källskrifter Till Lapparnas Mytologi [Sources for Lapland Mythology]: Stockholm.

Siikala, A. L. (1981). “Finnish Rock Art, Animal Ceremonialism and Shamanism”, in, Temenos: Studies in Comparative Religion, Presented by Scholars in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden 17. Helsinki: Finnish Society for the Study of Comparative Religion, pp. 81–100.

Solbakk, A. (2018). What we Believe in. Noaidevuohta – An Introduction to the Religion of the Northern Sámi. New Expanded Edition: ČálliidLágádus, Kárášjohka.

Sommarström, B. (1987). “Ethnoastronomical Perspectives on Saami Religion”, in, Saami Religion. Based on Papers Read at the Symposium on Saami Religion Held at Åbo, Finland, on the 16th-18th of August 1984, ed. T. Ahlbäck, (Published by the Donner Institute for Research in Religions and Cultural History), Åbo & Stockholm 1987. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis XII, pp. 211–250.

Taavitsainen, J-P. (1979). Suomussalmen Värikallio, Kalliomaalaus Nämforsenin ja Itä-Karjalan Kalliopiirrosten Välissä. Kotiseutu3–4/1979, pp. 109–117.

Tafjord, Bjorn Ola. (2013). Indigenous Religion(s) as an Analytical Category. Method and Theory in the Study of Religion 25. Published by Brill, pp. 221-243. DOI: 10.1163/15700682-12341258

Taskinen, H. (1999). The Värikallio Rock Painting, Suomussalmi. Published by the National Board of Antiquities, Helsinki.

Whitaker, I. (1957). “The Holy Places of the Lapps (English Summary)”, in, E. M. Manker: Lapparnas Heliga Ställen: Kultplatser och Offerkult I Belysning av Nordiska Museets och Landsantikvariernas Fätundersökningar [The Sacred Places of the Lapps: Cultures and Offices in Light of the Nordic Museum and the National Anthropological Surveys]: Stockholm, Sweden: Acta Lapponica 13, Geber, pp. 295–319.

Interview Material

Rissanen, A. (2006). The Content of the Painted Panel at Hossa, Suomussalmi.

Endnotes

[1] The online version of the article can be found via the following link. It should also be noted that the sieidi head with facial features is impossible to see when up close to the rock paintings but much more recognisable from across the other side of the lake on an elevated view, as is demonstrated in the 2007 publication. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299469160_Shamanism_at_Rock_Art_The_Dancing_Figure_and_Stone_Face_at_Hossa_Northern_Finland Also and in addition, it should be noted that in the article there are different ways myself and other scholars whose sources have been used who refer to the Sámi people homographically, for instance, Sámi, Sami, Saami and Samek. These terms vary in Sweden, north, south and Norwegian Sámi areas,

[2] It should be noted too how there is a prehistoric rock painting at a location called Julma Ölkky which is in Kuusamo consisting of two human figures and what looks like an animal, possibly a reindeer.

[3] For ethical reasons I am emphasizing here that there are approximately 70 sacred drums that were taken during missionizing from Sápmi to European Museums in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and where most of them still remain today. These are the countries where the majority are currently held: Germany, Sweden, Italy, France, United Kingdom and Denmark.

[4] Text translated from Finnish to English by Anja Rantanen.

[5] Examples of such holy places can be found in the work of Ernst Manker: Lapparnas Heliga Ställen: Kultplatser och Offerkult I Belysning av Nordiska Museets och Landsantikvariernas Fätundersökningar (1957). There are two pages at the back of the book where the photographic data is on plates 172 and 173.

[6] See for example, Milton Núñez: Reflections on Finnish Rock Art and Ethnohistorical Data (1995).

[7] See the link for the online version of the article. https://www.folklore.ee/folklore/vol11/pdf/sami.pdf

[8] Reuterskiöld 1910, op. cit., 27.

[9] For a more recent photograph of the large deer or elk on the Hossa panel, see Ismo Luukkonen’s book: Suomen Ensihistorialliset Kalliomaalaukset (2021), pages 286-287).

[10] Other scholars have put forward theories about the presence of deer high on rock art panels that are located on cliffs with anthropomorphic imagery as being associated with the sky. For example, see the work of Antti Lahelma (2005 and 2007); Pekka Kivikäs (2001) and Osmo Pekkonen (1999).