1 Möbius Strip, mixed-media performance

Figure 1. A Möbius strip. Wikimedia Commons

This article is the continuation of my recent publication Enacting peripeteia in Möbius Strip: Adapting Butoh principles in mixed-media performance (2023) and attempts to untangle the theoretical framework of Möbius Strip (when in italics, it refers to the performance and not to the mathematical concept).

To facilitate the reader’s understanding, a brief description of the duet performance Möbius Strip which was part of my ongoing post-doctoral research follows. The post-doctoral research focus is upon enacting alternative time embodiment in multi-sensorial performative praxis[1] (Kolliopoulou, 2023a). I engaged in Möbius Strip wearing the multiple hats of researcher, director, sound editor, video maker and performer. The performance was shown in Corfu (March 2023) and in Athens (June 2023)[2].

Möbius Strip was accompanied by:

a. The experimental short film Carpe diem 2 (2023). Carpe diem 2 (the elaboration of Carpe diem[3]) narrates violence as a complex phenomenon that occurs in society, in nature and in the relation with ourselves.

b. A soundscape (audio collage) of pieces by Steve Reich (Drumming), Allegri (Miserere) and Iannnis Xenakis (Psappha).

Möbius Strip was structured into different scores/atmospheres that narrate the story of two opponent soldiers involved in a war:

a. The (de)construction of the flag narrates the reason for the separation of the adversaries,

b. The outbreak of hostilities depicts how an explosive situation foments violence,

c. Cleaning the battlefield occurs when the involved enemies miss the opportunity to retreat,

d. Reeling into the battlefield refers to the theater of war when violence is exculpated.

d1. Reeling into the battlefield: peripeteia is an unfortunate twist of plot in the situation when both soldiers are fatally wounded,

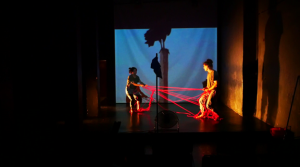

d2. Reeling into the battlefield: re-discovering humanism is a moment of insight that follows peripeteia, urging the enemies to reconsider their principles and act appropriately. (See Figure 3)

1.1 Discovering alternative bondages in the Anthropocene.

The article suggests that war must (unfortunately) be included in the long list of anthropogenic ecological disorders. Its consequences, especially the long-term ones, for example nuclear explosions, have an impact that can be extensively observed in natural ecosystems, human lives, and cityscapes. Hence, it might be argued that war is one of the crudest symptoms of the Anthropocene.

Donna J. Haraway points out that:

The Anthropocene is determined by its textures: […] the issues about naming relevant to the Anthropocene, Plantationocene, or Capitalocene have to do with scale, rate/speed, synchronicity, and complexity. (Haraway, 2015 quoted by Kolliopoulou, 2020).

In this respect, Butoh comes into play and becomes relevant, as a dance form articulated around the embodiment of situations rather than a movement-based choreography. Both Butoh and the Anthropocene are driven by internal human mechanisms that manifest themselves through external forms. In other words, we could describe them as life-motors or complex systems that emerge out of basic principles that are expressed through textures. Butoh is concerned with the embodiment of death-life forms expressed in a poetic way through the body of the performer, which is here seen as an ensemble of frequencies spanning from birth through dispersion. The Anthropocene is a manifestation of the expansion of (self) destructive human activity on earth; its discordant vibrations affect our body textures.

Butoh and the Anthropocene are ontologically correlated since they do not only advocate but they actually embody a perspective on human nature. As such, they are not simply added to the existing ecosystem, but also have the potential to alter it.

This article aims to steer peripeteia which is taking place as a Möbius strip mixed-media performance. The performance synthesizes the philosophical elaboration of the paradoxical mathematic concept of Möbius Strip.

My artistic research is informed by Butoh-fu principles. Möbius Strip emerged as a response to a current flaming issue, specifically the war crisis that erupted in Ukraine and its global repercussions. Sadly, since Möbius Strip was created, there has been an escalation of warfare around the globe, having at its peak the ongoing Gaza Strip military operations and the Nagorno Karabakh issue. The current political scenery is giving the impression that a domino effect is under way. The performance attempts to shed light on the philosophical and existential quests that foment conflict among nations and give birth to wars. The phenomenon of war is here seen as a sociopolitical facet of the Anthropocene.

The hypothesis here is that if those questions remain unanswered, by default they will perpetuate Anthropogenic disasters. In fact, what we are currently witnessing is a vicious circle. The article suggests possible ways of escaping from this situation of perpetual violence, which is manifested as a static system that needs to be readdressed from a fresh perspective. My claim is that by adopting alternative modalities of facing reality we might reach a rearrangement of the systemic dynamics. It would be necessary to nurture our doubt on what is there. That would allow some openness to this hermetically sealed belief system which is rooted in the Anthropocene.

Figure 2. Pic from the video Carpe diem 2

1.2 The Butoh-informed dramaturgy of Möbius Strip

The dramaturgy of the performance has been gradually developed in the studio, having as its starting point the Butoh-fu World of Burnt Bridges delivered, among others, by Yukio Waguri. Butoh-fu is retrievable in Butoh Kaden (Waguri, 2020a) and in the portal of Hijikata Tatsumi Archive, Keio art center[4]. Butoh Kaden consists of 7 Worlds reflecting on different atmospheres (frequencies) that trigger upon Butoh dancers a variety of body movement qualities (textures).

The 7 Worlds reported in Butoh Kaden[5] are: World of Abyss, World of Flower, World of Wall, World of Bird and Beast, World of Neurology Ward, World of Anatomy and World of Burnt Bridges. The latter refers to the destroyed cities and war-ravaged landscape. Möbius Strip availed of this Butoh-fu imagery as a starting point to unfold in a studio-based dramaturgical research process.

Waguri, in his essay Considerations on Butoh-fu, mentions that Butoh-fu is a transferable system that:

Uses words and images to introduce the observer to an imaginative Butoh space. Also, it manages and shares time and space, via physicalizing imagery through words. (Waguri, 2020b)

Waguri explains that the embodiment of helplessness, sense of loss and despair is at the heart of the World of Burnt Bridges. He further mentions that the choreography made by Butoh-fu is characterized by Naru (Becoming). Naru means transformation, or rather possession. A frequent theme of Butoh is ‘the continuous transformation of the two-dimensional space of the painting into the four-dimensional space of Butoh.’ (Ibid)

To circumscribe Butoh as a method we might say that its core aspects are becoming and/ or being in a constant state of transition (Smith, 2017) that expands the visible limits of the body to the space and the time that is created by the performer.

1.3 The concept of Möbius Strip: embodying paradox

However, as Waguri states in his essay (Ibid) it is important to clarify that although one ‘becomes’ the things that Butoh-fu designates, if one completely becomes it, there is a possibility that the choreography received externally may not have any effect on their audience. The reason is that if the performer is entrapped in their own embodiment, they risk being self-referential and non-communicating anything to the spectator. In that case, their performance will be perceived as a certain state of trance. For this reason, it is necessary to underline that in Butoh-fu embodiment:

[…] living in an imaginative space, becomes necessary. That is the state of awakening, being self-aware, and being able to manage oneself […] Hijikata’s Butoh, brought his intense ego and spirit of negation to the cultural situation of Japan, in which the concept of the individual has shallow roots. (Waguri, 2020)

The Butoh dancers strive to cultivate and master a two-directional attention inside and outside their body-mind to synthesize a two-states presence. In this respect, the Butoh method resonates with the Möbius Strip model: having two sides while being interlinked with one another.

Moreover, it is of salience to highlight that Butoh, as every form of art, emerged out of the needs of its historical period in Japan, having (among others) an intrinsic quest to restore the neglected sense of subjecthood lost in the vortex of nationhood during World War II. As a result, Butoh dancers are asked to maintain continuously and contemporaneously a double presence: the inside (individual) and the outside (social).

As Tanya Calamoneri notes,

the transition which was manifested in dance “through both Wigman (Mary) and Hijikata’s work — post WWI Germany and post WWII Japan — is one from dancing body as form to dancing body as site of experience […]. (Calamoneri, 2014, p. 37)

Hence, the body in post WWI Germany’s and post WWII Japan’s dance scenes is not addressed any more as a mere compositional tool in choreographic practice or as an expresser of virtuosic technique, but rather as a vessel of lived experience.

The suggestion here is that this two-fold quality of presence of the performers but also the situation of the war-sparkling conflict resonates with the mathematical concept of Möbius Strip.

Möbius Strip is apparently a two-sided strip that, because of the unusual modality of bondage, behaves as one surface. The concept of Möbius Strip is deployed as a metaphor in this work to signify that, however in wartime the opponents are clearly seen as two (or more) separated and divided sides, this happens only because their actual (non) bondage is not allowing them to be in harmony as one. (Kolliopoulou, 2023a, p.35)

1.4 Understanding the holographic nature of Butoh-fu

To understand Butoh-fu and how it has informed the choreography of Möbius Strip, it is important to distinguish the difference between the terms ‘multi-layered’ and ‘blended and opaque’. Waguri suggests that:

[…] There is a dance hidden in between each of the Butoh worlds. The way of transitioning between each world decides the speed and density of the dance, and this density builds up the strength of the dance. (Waguri, 2020)

Similarly, Möbius Strip has been articulated through interlinked image-states that form a chain of events. However, the image-states do not constitute a puzzle formed by discrete pieces, but rather a ‘soup’ that comes to life after ‘mixing and cooking together a variety of ingredients.’ I am borrowing the metaphor of cooking from Tadashi Endo (Endo, 2023). He is a second generation Butoh master and disciple of Kazuo Ohno.

I worked with Endo in December 2022 on his Butoh intensive workshop offered at the MaMu Butoh Center at Göttingen. During the workshop, he often used cooking as a metaphor for dancing. He kept mentioning that choreographic practice could also be seen as the preparation that takes place before cooking. Endo said that in both cases we slice (sculpting of movement), we cut (eliminating parts of choreography that are redundant), we mix (composing the final piece by assembling its discrete parts), we spice (adding pauses or accents when necessary), and we taste (performing for the audience and asking for feedback). In all the above processes, the duration is a matter of adjustment to the variable materiality, which also dictates the behavior of the ingredients. The latter is ultimately induced by their nature.

When cooking, we use vegetables, salt, water, and oil to prepare the ‘soup’; in choreography we use space, time and our body (altogether equal to experience) plus our emotions and ideas to address the audience.

In both cases, a dynamic dialogue between the creator (cook/ choreographer) and its material (meal/ dance) is evolving, leading into a final recipe/ dramaturgy. Endo is metaphorically alluding to the fact that the creative process of shaping the final artwork (food/ dance) is a process of synthesis that entails an intuitive approach of intermingling rather than analytic thinking of assemblage. Under this prism, this article suggests that, according to Endo, Butoh is holographic. To clarify Butoh’s holographic nature, it is helpful to mention an explanation by Thomas Kasulis.

Kasulis borrows the paradigm of jigsaw puzzles as an example of holographic entities[6]. In jigsaw puzzles,

Each piece has information not only about adjacent pieces, but also about all the other pieces in the whole. That is, the whole is not simply made of its parts, but also, each part contains the pattern or configuration of the whole of which it is a part. Such holographic relations between whole and part are common in Japanese philosophical systems. (Kasulis, 2022, p. 5)

The intention here is to understand Möbius Strip as a choreographic practice under the prism of Butoh holographic modus operandi. The different scores/atmospheres of the performance are interlinked and evolve both in a conceptual and organic manner. Hence, the ending of Möbius Strip (reconciliation) is already contained within its beginning (war outbreak) like a seed already enclosing the potentiality of a plant that has yet to grow.

2 Time-space in Butoh: konpaku

Möbius Strip was created having the World of Burnt Bridges as a compass and by deploying Butoh training as a methodological tool to sensitize the psychophysical compresence of the performers. During the performance, performers allowed themselves to be affected by being observed by each other, as well as by the gaze of the audience.

Butoh as a choreographic method was of interest here because of the following:

Its subjects (articulated in its notation system known as Butoh-fu or generated on the spot by the Butoh masters during their teaching practice) are often driven by the urge to express the paradoxical coexistence of interpenetrating (see also in p.10) contrasting realities in life. In the same way that darkness and light are entrapped in a never-ending dialogue, Butoh performers seek to embody counteracting forces when they dance.

Similarly, in the Butoh-informed dramaturgy of Möbius Strip, both the heaviness of the warfare and its discordant antithesis with the careless and destructive decision-making of those who have the power to decide, are exposed.

Finally, Butoh lies in an uncharted territory between dance and performance art; it entails a specific training that enhances the mind-body receptivity and porosity to the open-ended dynamicity of time-space. This makes Butoh-informed training a malleable and promising choreographic tool that can be easily adapted and become responsive to an experimental performative approach.

When Kazuo Ohno[7], a prominent Butoh dancer, was teaching his students, he often used the term ‘konpaku’[8] to refer to the ‘ailing body’. The ‘ailing body’ is a characteristic state of presence in Butoh that ascribes a ghostlike and oneiric quality to the dancers’ movement.

Natsu Nakajima (Butoh dancer, disciple of Ohno) wonders:

Where is the field of ‘konpaku’? If there is a field of ‘konpaku’ it would neither be in the ‘heavens’ nor in ‘hell’. It is a term that describes the riverbanks where the dead and the living come and go. (Nakajima, 1997, p.4)

With the term ‘konpaku’, Ohno wished to demarcate the opaque time-space of the ‘ailing body’; Expressed by Hijikata with the term ‘suijaku-tai, the ‘ailing body’ was the desired body condition for the Butoh dancer.’ (Kolliopoulou, 2023, p.40) This quality of body condition heightens its permeability and malleability to embody different states of presence/ atmospheres via Butoh-fu. In an analogous way to Jane Bennett’s Vibrant matter (2010), the body in Butoh ideally loses its human connotations that is limiting its expressive potentiality and becomes a non-human entity in a state of transformation (naru). Ultimately, the body’s vibrancy is also directed outwards and affects space. The ‘konpaku’ time-space is fluid and not fixed, available to be transformed into something else.

The embodiment of the ‘ailing body’ occurs in Möbius strip when the two opposing soldiers are witnessing each other’s death. In this ‘konpaku’, all social constructions that have caused the death of the two soldiers are gradually blurred as they (the opponents) finally share something: the transit time of an ailing body from life to death; When they realize that we are all mortal and fragile, a transformation of their inner attitude is on its way. In the obscured time-space of war, a crack of light suddenly intrudes: peripeteia.

Figure 3: Pic from the video Carpe diem 2

2.1 Time-space as a vibrant field in Japanese phenomenology

In Proto-Shintō animism (ancient precursor of Japanese philosophy) it was generally assumed that

[…] We live in a world of internal relations where various forces and things can be distinguished, but in the end, they are never discrete but inherently interrelated in some way […] Reality is not a world of discrete things connected to each other, but more a field of which we are part (a field often expressed by the indigenous word kokoro). (Kasulis, 2022, p. 8)

Japanese philosophers typically view reality in terms of a complex system of interdependent processes. Thomas Kasulis underlines that, in most Japanese philosophies, oppositional polarities do not create dynamism, but rather, dynamism is the primary event out of which polarities emerge (Kasulis, 2022, p. 21). Similarly, in Möbius strip, the polarities (in this case, the two performers) do not have independent existence of their own but exist as vectors of activity. This also happens during wartime, when soldiers and nations find themselves being moved as mere puppets. They are moved by external decisional powers that apart from demolishing their nations (physically), they undermine their subjectivity. In addition,

The notion of ‘being moved’ as understood in Butoh, is one of its core principles […] One recurring image that is often used in Butoh is strings attached to every part of the body, extending out in all directions, and suspending the body in space. (Smith, 2007, p.17)

According to Presocratic philosophers who were mainly interested in cosmology, space was conceived as some sort of vessel or as a very delicate corporal medium within which material bodies are floating as if connected by invisible strings. On the other hand, time was commonly considered as a stream that flows. The idea of time as passage relates to the idea of events changing from future to past while, in addition, the concept of time is chiefly associated with the term of duration. Anaxagoras, in his Theory of Everything, sustained that time was connected to space through the constant change of things and ideas (flow).

In this respect, it is relevant to mention Nishida Kitaro, a modern Japanese philosopher, and founder of the Kyoto school who coined the term Basho which literally means place. The concept of Basho ‘points to a dynamism that precedes any intellectual dichotomization between experience and reality.’ (Krummel & Nagamoto, 2011, p.11) Nishida suggests that we are not linked to the world in a subject-object relationship. Instead, we affect the world while being affected by it at the same time. Hence, our bond with the world has an interpenetrating character[9].

Besides, Nishida was particularly known for his work because he managed to bring together Zen Buddhism’s cultivation of a holistic form of meaning-making with the traditional philosophical methods of understanding that flourished in Japan. Nishida’s work focuses in describing a philosophical way of understanding the world that surpasses analytical thinking and is based upon intuition.

He saw time:

[…] as the continuation of discrete or discontinuous moments, and as such time has a spatial extension, inasmuch as space has a temporal direction […] Nishida considered predicates (persons) to be already contained in the field of consciousness in which the observer is embedded. (Wynn, 2020, p. 224)

Nishida’s thought was rooted into the idea that:

The world is a dialectical universe […] a place of mediation between acting individuals […] Topos does not one-sidedly determine individuals, but it is a topos that arises with them through their creative interactions. (Maraldo, 2019)

Nishida’s perception of the world as a dynamic time-space entity wherein individuals find themselves constantly in dialogue with their reality, resonates with Endo’s approach to the relationship between the artist/ creator and their artwork in Butoh dance.

This article claims that alternative time-space conceptions derived from Japanese phenomenological perspectives as well as paradoxical models in Mathematics such as Möbius strip could serve as means of inspiration to conceive possible solutions[10] in the era of the Anthropocene. This article acknowledges that those concepts encompass twists of reality that are not easily applicable and feasible. The hypothesis however is, that those concepts could be helpful to deconstruct any kind of answers phrased in hackneyed rumbling, upon truths that cannot be challenged, rules that cannot be reconsidered. Deconstruction stands at the core of every creative practice. Creativity is a human activity that attempts to re-read and re-compose reality. Ultimately, it is our acceptance of rusty nonfunctional conceptions that foments and perpetuates the Anthropogenic disasters, including war.

Michiko Yusa explains that:

For Nishida, the essence of the self lies in one’s creativity and expressive operations. This emphasis on creativity (poiesis, artistic and otherwise) is central to his definition of the person. We are born into this world as “that which is created” (tsukurareta mono), but we in turn become “that which creates” (tsukuru mono). (Yusa, 2005, p.4)

Yusa emphasizes that for Nishida creativity is fundamental; he is skeptical of societies that do not allow individual freedom to be creative and condemns historically what happens in totalitarian societies.

Figure 4: Pic from Möbius strip performance at Fournos lab[11], Athens

3 Towards an alternative Politics of time

Byung-Chul Han (2020), in his book The disappearance of rituals: a topology of the present, lists nationalism as a negative, fundamentalist form of closure. On the contrary, culture is a positive form that aids in providing an identity for a community. At the core of Han’s philosophical stance stands Michel Foucault’s thought, who claims that:

[…] from the economic point of view, neoliberalism is no more than the reactivation of old, second-hand economic theories […] from the sociological point of view it is just a way of establishing strictly market relations in society […] from a political point of view, neoliberalism is no more than a cover for a generalized administrative intervention by the state (Foucault Davidson Burchell, 2008, p. 130)

Foucault’s early work begins with the idea that the subject(ivity) is dead, rather than being the source of meaning because it is fundamentally produced by discourses, institutions, and relations of power. He considers the subject as social and historical rather than innate (Danaher, et al., 2002, p. 115).

In his later work, Foucault coined the term biopolitics to discuss the relation between the human body and institutions of power (Danaher, et al., 2002, p. 124). The basic idea of biopower (the way power is exercised in biopolitics) is to produce self-regulated subjects. Its discipline functions through a series of quiet coercions (Danaher, et al., 2002, p. 62) working at the level of people’s bodies. Those coercions silently shape the manner of how people see the world and, consequently, how they behave.

According to Han, aiming to achieve this subtle interference with people’s bodies, biopolitics functions, amongst others, through politics of time. Peter Osborne explains the term politics of time as follows:

A politics of time is a politics which takes the temporal structures of social practices as the specific objects of its transformative (or preservative) intent. (Osborne, 1995)

Möbius Strip is a choreographed performance that suggests Butoh as a method elaborating on the problematics arising from the current politics of time that shrink time’s meaning to fit into the service of a strictly product-oriented society. By giving emphasis on the experience of the Butoh dancers (and consequently, on the audience’s experience) when embodying different states of presence/ atmospheres inspired by Butoh-fu, time becomes process-oriented, and its socially constructed and goal-oriented nature is reassessed. The intention is to share the embodiment of Butoh-fu (while performing) with the audience, aiming to offer them stimuli of an alternative experience of time that could positively challenge the norms of their everyday life perception induced by biopolitics.

The hypothesis posed in my research is that the embodiment of time stimuli offered during the performance will become a new remembrance for the audience to return to. By cultivating the audience’s awareness of slow processes, hopefully they will begin to question themselves about the natural pace of things and become more responsive to their environment. This kind of subtle sensitization creates an extra filter in their perception that helps to distinguish what is abrupt and odd from what is harmonious. In principle, anthropogenic disasters (like war or pollution) are characterized by violence and lack organicity. By recognizing what is problematic, we make the first step in mobilizing our investment of energy in finding solutions.

Hence, Möbius strip acts as a pool of time embodiments in which the audience gently is thrown, aiming initially to sensitize and then to challenge the current politics of time. Sandra Fraleigh (2010), in her book Butoh: metamorphic dance and global alchemy, states that Butoh performances have an extended impact upon the audience through the activation of empathy. Another important aspect of Butoh is about letting the performer’s metamorphosis to occur in the here and now (becoming and transformation at Considerations on Butoh-fu) (Waguri, 2020). This subtle state of attention that arises when Butoh is performed is believed to affect the audience on a subconscious level.

Our temporal perception is deeply rooted upon our body-mind presence. According to Han, politics of time is a layer of Psychopolitics:

Foucault explicitly ties biopolitics to capitalism’s disciplinary form, which socializes the body in its productive capacity […] biopolitics concerns the biological and the physical […] it constitutes a politics of the body […] but neoliberalism has discovered the psyche as a productive force. This psychic turn — that is, the turn to psychopolitics — […] refers to immaterial and non-physical forms of production […] productivity is not to be enhanced by overcoming physical resistance so much but by optimizing psychic or mental processes. (Han, 2020, pp. 24-25)

Figure 5: Pic from the documentation of Möbius strip (2023) featuring Eleni Kolliopoulou and Stratos Papadoudis performing at Corfu, Polytechnon

Han’s discourse is founded upon the idea that the neoliberal regime is developed around the excess of positivity; This refers to our necessity of being constantly excited and in high spirits (especially in our social interactions) not allowing for negative emotions to be felt or even observed by others. Han notes

the emergence of what can be called self-referential optimism. This is a widespread, almost religious, belief that you must be optimistic all the time. This optimistic attitude isn’t grounded in something real or actual, but only in itself. You should be optimistic not because you have something concrete to look forward to but just for the sake of it. (Cikaj, 2022)

This becomes a constant but shallow search for the bright side of things, putting aside any dark aspects of reality (such as illness, grief, and loss) who are also present in our lives. According to Han,

[…] without negativity, life degrades into something ‘dead’. Indeed, negativity is what keeps life alive. Pain is constitutive of experience. Life that consists wholly of positive emotions and the sensation of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2008) is not human at all. (Han, 2020, pp. 30-31)

By posing the question of what is meant to be human in the context of the Anthropocene we are seeking solutions to our everyday common situations in relation to ecological disasters as warfare and climate change issues.

According to Achim Steiner’s (UNDP Administrator) report on Human development report in 2020:

The pressures we exert on the planet have become so great that scientists are considering whether the Earth has entered an entirely new geological epoch: the Anthropocene, or the age of humans. It means that we are the first people to live in an age defined by human choice, in which the dominant risk to our survival is ourselves. (Steiner, 2020)

The question of what it means to be human is also related to the human rights’ issue, to the ethics of human agency upon nature and to the emerging debates around the relationship between humanity and technology. All the above are interlinked to the Anthropocene and would determine its future. As such, they require our attention and care; they require time and space.

3.1 Ningen and the inter-corporeal self

Watsuji Tetsurō (Japanese philosopher, Kyoto school) uses the Japanese term ningen that is usually translated in English as human being. The word ningen is composed of two words. The first word, nin, means person and the second word, gen, means space or between. ‘Thus, the word ningen in his thought emphasizes the meaning of ‘betweenness’ between human beings […]’ (Tetsurō & Bownas, 1961, p.8)

According to Tetsurō the Japanese concept of a person (ningen) has a twofold structure as both an individual existence in time and a social existence in a climate (fudo) of space. This way, Tetsurō introduces the fundamentals for environmental ethics (ecological thinking). His suggestion is that the ‘self’ arises from a relationship between what is individual (which could be also seen as private) and what is social (or related to the public sphere). In this respect, he uses the term spatial climate to include both human society and living nature.

Tetsurō sustains that whatever exceeds the boundaries of the self, belongs to the spatial climate. He believes that personhood is created out of this tension resembling an elastic band that connects the primordial self (oriented to the satisfaction of our basic needs and desires) with the civilized self (in sought of acceptance and exchange with the Other). This elastic band is a channel that allows vibrations to travel from one side to the other, like a Möbius strip enabling synthesis. In Möbius strip this translates to the person (nin) finding themselves on the battlefield (gen), a soldier.

To this tension between the individual and its environment (named by Tetsurō as ningen), Merleau-Ponty adds another one, the inner tension, namely inter-corporeality, which refers to the dynamicity of the bondage between the body and its environment; ‘With the term inter-corporeality, Merleau-Ponty acknowledges and highlights the importance of the context in what forms reality.’ (Kolliopoulou, 2020, p. 38)

Inter-corporeality is a term that resonates with Tetsurō’s climate and gives emphasis to the modalities of connectivity among individuals and society at large. The concept of climate is ultimately based on Tetsurō’s treatment of the body. As Joel Krueger notes:

The body has an irreducibly “dual structure,” according to Watsuji. It is simultaneously an object as well as an experiential dimension, a bodily subjectivity […] The lived body is not strictly speaking a content of consciousness (such as, e.g., the visual perception of a tree or the memory of a childhood experience). Rather, the lived body is our anchored first- perspective on the world. (Krueger, 2013, p. 128-129)

It is important to note that whereas both Tetsurō and Merleau-Ponty appraise the centrality of the context and its potentiality to shape and to be shaped, we note that the latter particularly insists on the ability of the body to remain porous and receptive to its environment. Ultimately, we might argue that Merleau-Ponty’s point of view underlines the centrality of the body as a perceptive lens of reality, while Tetsurō tends to express a less anthropocentric stance that is often encountered in Japanese phenomenologists.

3.2 Butoh-fu and radical imagination

This article conceives Butoh-fu as the trigger of opening an internal space within each performer and, hopefully, within each person in the audience. This process of discovering and subsequently delving into the internal space, has been steadily cultivated during Möbius strip studio-based research (training). The opening of internal spaces allowed the performers to embody specific atmospheres/scores.

Hence, Möbius Strip methodology could be summed up as a conscious effort leading to the discovery of our internal space (during the training) and its nourishment out of mental imagery (Butoh-fu), that gradually acquired a concrete form (performance). The article sustains that claiming individually our creative time/ space could be seen as a conscious political action which could implicitly shift our perception of reality.

Cornelius Castoriadis bases his ontology of creativity on the concept of radical imagination, which is based on psychoanalytic theory by S. Freud.

Radical imagination is defined as a constant flow of presentations, feelings and intention, which cannot be given a fixed definition. (Tovar-Restrepo, 2012)

Castoriadis in his theory of ontology of creativity, explains the layering of the soul and its subjective contents. Contrary to Foucault, he suggests that the maintenance and nourishment of an individual space for self-reflection would offer the potentiality of transformation towards the direction of freedom, both at an individual and a social level. Castoriadis considers that psychical representation (radical imagination) is an immanent condition, ability and quality of the soul that exists before any other organization of the impulses or any real experience.

Ultimately, it is because of radical imagination that human beings can create their own individual and social reality; the soul is creative by nature and is expressed through malleable things. Moreover, for Castoriadis, imagination is iconoclastic, which means that it deconstructs and consumes all pre-given images of self (and reality).

The true polarity is between society and the psyche… These are both irreducible to each other and effectively inseparable. (Castoriadis, 1994: 148 quoted by Ross, 2018:72)

Radical imagination reminds us of the elastic band that connects Tetsurō’s individual and social self (see p. 14) and a Möbius strip (if seen as a process of bondage between the collective and the individual).

4 Agency and transformation: a comparative analysis

The Japanese time-space perception envisions the world as a magnetic field that is articulated by the presence of various agents, and it shapes their actions back in a perpetual flow. This perspective places greater emphasis on the situation that is unfolding rather than on the agency of the engaged acting forces.

In contrast, the plot of Ancient Greek Drama is developed around a tragic event/situation that urges an ethical decision to be made by the protagonist (tragic hero) who is faced with a dilemma. Finally, the tragic hero’s decision affects the development of the plot and interferes with the way the tragic situation is unfolding.

In this way, the plot of Ancient Greek Drama incorporates peripeteia as the decisive turn in time-space when the tragic hero is faced with an unpreceded situation. Being confronted with a vital and crucial dilemma and as a result of the embodiment that this new situation generated, the tragic hero changes perspective upon things (transformation).

Figure 6: Pic from Möbius strip performance at Fournos lab, Athens

This fundamentally different way of spatial perception is evident in the European philosophers’, starting from ancient Greek philosophers’ “ideation of ‘being’ instead of ‘arising from conditional causation’ in the eastern. (Lee, Myung-jin, Michael, 2009 17:02 min quoted by Kolliopoulou, 2020, p.34)

Nishida’s worldview places great importance on the fact that we can change and affect our reality, while, at the same time, he draws our attention to the ways that we are affected by it. Hence, it could be argued that, while in both cases (i.e., Japanese phenomenology and Ancient Greek Drama) the interrelation (bondage) between an ongoing situation and the individual’s perspective is acknowledged, we note that in Ancient Greek Drama the potential of the individual to undergo transformation is highlighted.

4.1 Actors’ peripeteia in Möbius strip: katharsis & flower

According to Aristotle in his Poetics, peripeteia1[12] (Greek: “reversal”) is the turning point in a drama, after which the plot moves uninterruptedly to its finale. It is the shift of the tragic protagonist’s fortune from good to bad, which is essential to the plot of a tragedy. Aristotle explains that peripeteia is followed by a moment of instant awareness whereby the tragic hero reaches deeper understanding of reality.

This article attempts to link peripeteia to other principal concepts encountered in the Ancient Greek drama and the Japanese theater as Noh and Kabuki—here seen as the precursors of Butoh. Lazarin (with reference to Aristotle) describes the cathartic effect of Ancient Greek drama mentioning that:

The states of mind that accompany the most intense and therefore effective, cathartic experiences are astonishment (εκπληκτικός; Poetics 1460 b27) and wonder (θαυμάσιος, Poetics 1452a4). (Lazarin, 2006 p.209 quoted by Kolliopoulou, 2020 p.193)

Lazarin explains that according to Aristotle, katharsis should occur:

At the climactic movement and follow naturally from the construction of the plot and the motivation of the character. (Ibid)

Hence, we could also define katharsis as the feeling of resolution that comes after the embodied knowledge gained via peripeteia, when being faced with the nonsensical nature of reality. Katharsis has a healing potential for both the audience and the tragic hero.

Lazarin comments that through the experience of astonishment and wonder that both performer and audience experience in peripeteia,

Katharsis occurs as a clear marking point or separation from the ordinary state of affairs: transcendence […] the ultimate aim of dramatic performance is to move the audience to a new and presumably higher level of consciousness. (Ibid)

Aristotle’s definition of Tragedy sheds light on the term katharsis as follows:

Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and possessing magnitude; in embellished language, each kind of which is used separately in the different parts; it is a mode of action and not narrated; and effecting through pity and fear the katharsis of such emotions. (Aristotle 1449b Poetics 6)

Reassuming, katharsis is an emotional shift induced in the spectator throughout the embodied action of the actors who find themselves in a liminal experience, that is peripeteia. Katharsis has a transformational effect on the performer(s) and the audience which resonates with Butoh’s metamorphic journey. (Fraleigh, 2010)

Zeami, the greatest playwright and theorist of the Japanese Noh theater, was fascinated by human emotions which go beyond the rational. His research has been concentrated on identifying the modalities in which performers and their audience are steered to a transformation state that exceeds and transcends everydayness. Zeami used the metaphor of a flower to refer to the transformation of the self as an active process:

Form is, so to speak, a bridge between the will and the body. In other words, the artist creates an agreement between himself and nature. And in this process of struggle with his materials and his body […] the object of his concern is nature. (Masakazu & Matisoff 1981, p.215 quoted by Kolliopoulou, 2020. p.189)

Figure 7: Pic from Möbius strip performance at Fournos lab, Athens

Zeami insists on the fact that to reach the flower (transformation) the actors need to be active both in their body and mind: ‘for the true Flower, the cause of its blooming and also of its falling is in the will of the actor.’ (Zeami 2010, p. 96, quoted by Kolliopoulou, 2020, p.190) He envisions the body-mind in its organic ensemble as the attainment and cultivation of the flower.

Zeami places great importance on the willpower of the actor to master the body-mind: The nonsensical is the primal material of the actor and it is stored within the actor’s body. If ‘tamed’ and channeled through technique, it creates the Japanese Noh theater.

What is more nonsensical than the theater of war, where established values and principles are overturned in a terrifying and absurd way? In Möbius Strip, peripeteia takes place in the dynamic time-space of escalating warfare, when two fatally wounded soldiers suddenly realize that they have more things that bind them together than reasons to fight each other. Their peripeteia occurs in the ‘konpaku’ of their death. Their katharsis is the realization that they are made from the same ‘flesh’ (Castaño, 2019). As Merleau-Ponty calls it in his attempt to understand the ontology of the body in-the-world, ‘he and I are like organs of one single ‘intercorporeity.’ (S, 168/ 274 quoted in Marratto 2012, p. 144).

Ultimately, we could conclude that flower and katharsis occur from the actors’ embodiment of the action, and they point to the relational self. The concept of flower exposes the struggle of the actors to master their body-mind as their primal material for their art, whereas peripeteia and consequently katharsis mobilize the tragic hero to a greater awareness of their attunement in the world. Ultimately, this relational self is in an ongoing process of transformation between the self and the other: like a Möbius strip twirling out of the Anthropocene.

Endnotes

[1] https://avarts.ionio.gr/en/department/people/665-kolliopoulou/

[2] http://www.elenivisualart.eu/interruption-ineffability/mobius-strip-mixed-media-performance/

[3] http://www.elenivisualart.eu/interruption-ineffability/ordinary-people-video-performance-2022/

[4] http://www.art-c.keio.ac.jp/en/archives/list-of-archives/hijikata-tatsumi/

[5] https://butoh-kaden.com/en/worlds/

[6] In the etymological sense that the whole (holo-) is inscribed (-graph) in each of its parts.

[7] http://www.kazuoohnodancestudio.com/english/kazuo/

[8] The Japanese word is: 魂魄[Hiragana: こんぱく] meaning ghost, soul, apparition, ghostlike

[9] Basho has been explored later by Nishida’s student Keiji Nishitani (1982) who coined the term Circuminsessional Interpenetration.

[10] Apart from being a means of dealing with a difficult situation, a solution has also the meaning of compound between two or more liquids, a synthesis.

[11] https://www.facebook.com/FournosLab/

[12] https://www.britannica.com/art/peripeteia

Images 2-7 are author’s pictures.

References

Aristotle, (1984). Poetics, trans. Ingram Bywater; Modern Library College Editions, New York.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Calamoneri, T., (2014). Bodies in Times of War: A Comparison of Tatsumi and Mary Wigman’s Use of Dance as Political Statement. Congress on Research in Dance Conference Proceedings, Volume 2014, p. 32–38.

Cikaj, K. “Are We Living in Byung-Chul Han’s Burnout Society?” TheCollector.com, https://www.thecollector.com/byung-chul-han-burnout-society/ (accessed November 30, 2022).

Curd, P., (2008; online edn, Oxford Academic, 2 Sept 2009). ‘Anaxagoras and the Theory of Everything’, in Patricia Curd, and Daniel W. Graham (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195146875.003.0008, accessed 25 Oct. 2023.

Danaher, B., Schirato, T. & Webb, J., (2002). Understanding Foucault. Cambridge: SAGE Publications.

Dufresne, T., (2000). Tales from the Freudian crypt: The death drive in text and context. Broadway: Stanford University Press.

Endo, T., (2023). http://www.butoh-ma.de/ Accessed on 15th June 2023.

Foucault, M.; Davidson, Arnold. I.; Burchell, G., (2008). The birth of biopolitics: lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979, Springer.

Fraleigh, S., (2010). Butoh: Metamorphic Dance and Global Alchemy. s.l.: University of Illinois Press.

Fraleigh, S.H. and Nakamura, T., (2006). Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo. New York; London: Routledge.

Han, B.-C., (2017). Psychopolitics: Neoliberalism and New Technologies of Power. London: Verso Books.

Han, B.-C., (2020). The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. Cambridge: UK: Polity Press.

Haraway, D. (2015) Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin. Environmental Humanities 6, no. 1 p.159–65. doi: 10.1215/22011919-3615934. Accessed on 10th January 2024.

Harman, G. (2015). Object-oriented ontology. The Palgrave handbook of post-humanism in film and television, 401-409.

Héctor G. Castaño (2019). A Worldless Flesh: Derrida, Merleau-Ponty and the Body in Transcultural Perspective, Parallax, 25:1, 42-57, doi: 10.1080/13534645.2019.1570605. Accessed on 10th January 2024.

Kasulis, T., (2022). Japanese Philosophy. In: E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman, eds. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2022 ed. s.l.: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Kolliopoulou, Eleni (2023), ‘Enacting peripeteia in Möbius Strip: Adapting Butoh principles in mixed-media performance’, Choreographic Practices (Journal) Intellect, 14:1, pp.27–49.

Kolliopoulou, E., (2023) Möbius strip, live performance Available at: http://www.elenivisualart.eu/interruption-ineffability/mobius-strip-mixed-media-performance/ Accessed on 17 April 2023.

Kolliopoulou, E., (2020). The body of the relationship: a practice-based exploration of the relationship between the body and its environment informed by the notion of Butoh-body: three case studies in time-based art (Doctoral dissertation, Ulster University).

Krueger, J., (2013). Watsuji’s Phenomenology of embodiment and social space. Philosophy East and West, 63(2), 127–152. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43285817 Accessed on 10th January 2024.

Krummel, JWM., Nagatomo, S., (trans) (2011). Place and dialectic: Two essays by Nishida Kitaro. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Loughnane, A., (2016). Nishida and Merleau-Ponty Art, “Depth,” and “Seeing without a Seer”. January.p. 47–74.

Maraldo, J. C., (2019). Nishida Kitarō. In: E. N. Zalta, ed. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2019 ed. s.l.: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Marratto, S.L., (2012) The Intercorporeal Self: Merleau-Ponty on Subjectivity. State University of New York Press (SUNY Series in Contemporary French Thought).

Masakazu, Y. and Matisoff, S., (1981) The Aesthetics of Transformation: Zeami’s Dramatic Theories. Journal of Japanese Studies, 7 (2), 215-257.

Merleau-Ponty, M., (1962) Phenomenology of perception. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Mikami, K., (2016). The Body as a Vessel: Approaching the Methodology of Tatsumi’s Ankoku Butō. Transl. by Rosa van Hensbergen. Ōzaru Books.

Nakajima, N., (1997) Ankoku Butoh. Lecture delivered after the invitation by Prof. Lynda Scott, ‘Feminine Spirituality in Theatre, Opera and Dance’. Taipei: Fu Jen University.

Nishitani, K., (1982). Religion and nothingness. Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

Osborne, P., (1995). Politics of Time: Modernity and Avant-garde. London: Verso books.

Ross, L., (2018). The mad animal: On Castoriadis’ radical imagination and the social imaginary. Thesis Eleven, 146(1), 71-86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513618776710

Shen, Y., (2021). The Trio of Time: On Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Time. Human Studies, Volume 44, p. 511–528.

Smith, H. S., (2017). Being moved: the transformative power of Butoh: towards an articulation of an aesthetics of Butoh. Monash University. Thesis. https://doi.org/10.4225/03/58b8c240a030c Accessed on 10th January 2024.

Steiner, A., (2020). The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (Foreword). UNDP. Accessed on 31st August 2023.

Tetsurō, W., & Bownas, G. (1961). Climate and culture: A philosophical study. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Tovar-Restrepo, M., (2012). Castoriadis, Foucault, and Autonomy: New Approaches to Subjectivity, Society, and Social Change. London: A&C Black.

Waguri, Y., (2020). Butoh Kaden: World of Burnt Bridges. https://butoh-kaden.com/en/worlds/burnt-bridges/ Accessed on 12th June 2023.

Waguri, Y., (2020). Butoh Kaden: Consideration of Butoh-fu. https://butoh-kaden.com/en/consideration/ Accessed on 12th June 2023.

Wynn, L., (2020). The Concept of Space and Time in Japanese Traditional Thought. June.

Yusa, M., (2005). Nishida Kitarō Encyclopedia of Religion. Encyclopedia.com. (October 19, 2023). https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/nishida-kitaro

Zeami, and Wilson, W.S., (2010). The flowering spirit. Classic teachings on the art of No. Tokyo; New York: Kodansha.