Politics are becoming increasingly personalized, the focus shifting from party policies to individual candidates. Throughout the world, social media plays a significant role in this transformation (Enjolras & Karlsen,2016; Garzia, 2011; Kruikemeier, et.al., 2016; Larsson, 2014; Small 2010; McAllister,2007; Meeks, 2017). The most common definition of the term personalisation phrases it simply as a dichotomous relationship between the importance placed on the candidate on the one hand and the party on the other (Chan, 2018). Compared to other countries, Icelanders are very active on social media with 92% of the population owning a Facebook account, while 62% use Snapchat. Other social media are used less, Instagram 44% and Twitter 20% (Gallup, 2017). Electoral volatility has furthermore been on the rise in the last two decades with diminishing party loyalty and partisan dealignment (Harðarson, 2008, 2016). Dealignment in turn creates a dynamic context for personalization and leadership focus vis-á-vis party attachments (Garzia, 2011; Garzia, et. al. 2018). This rising trend of dealignment, as Lobo (2018) has pointed out, correlates with the phenomenon of personalization (Lobo, 2018).

Precisely this tendency was felt in Iceland before the 2017 parliamentary elections, e.g. in the case of the now prime minister of Iceland, Katrín Jakobsdóttir, who had become more popular in the polls than her party (Jóhannsson, 2016. Magnússon, 2017).

Traditional media and their news values are partly responsible for keeping up the visibility of political leaders on the news agenda, as normally they are considered more newsworthy than ordinary MPs or candidates. Thus, personalization is enhanced by the media, not only traditional media but social media as well. There are two cornerstones to all recent research into social media and politics: the Obama campaign of 2008 and the Trump campaign of 2016. These elections were not exclusively held nor won on social media but innovated its use to attract more attention and votes (Chadwick, 2017).

However, Scandinavian research has shown that in the fragmented hybrid media environment in European parliamentary democracies, social media have as well become a vehicle for non- leaders and newcomers who use these platforms proportionally more than their leaders (Blach-Örsten, et.al, 2016; Larson and Moe, 2014).

The aim of this paper is to find out if politician´s usage of social media, not only of leaders, contributes to the personalization of the Icelandic political system, which has historically been party centred (Harðarson, 2008). This will be done through a content analysis of the posts on social media of top two candidates of every party in every constituency before the 2017 parliamentary elections and with post- election semi-standardized interviews with 5 party officials. We will explore whether social media is more party, or candidate centred, gaining insight into why that is and what we can expect to see in the future through the interviews. As no research exists on the effect of social media on personalization in Iceland, this will be the first attempt at such analysis.

Literature review

It should be noted at the outset that personalization of politics is not a new thing. It has been growing ever since the first televised debates, decades before the first social media emerged. However, electronic media have led to an accelerating pace of personalization (McAllister, 2007).

Social media does not determine who wins or loses an election, as the hybrid media system has led to all media being interconnected (Chadwick, 2013, 2017). Indeed, people post stories from traditional media on social media and the traditional media covers posts from politicians on social media, the tweets of Donald Trump being an extreme case in point. Social media is, however, a very important tool in a system of hybrid media, where two different types of media logic, traditional media logic (one to many) and network media logic (many to many), interact and coexist in new and dynamic communication fora (Klinger & Svenson, 2014). This is particularly important with respect to personalization as more votes are potentially available than before because of the decline in partisan alignment which leads to more undecided voters (Garzia, 2011).

Drawing on the experience from many elections where social media has played a part, party officials and spin doctors have become more confident in the use of social media and less afraid to lose control of the conversation about their candidates on social media (Chadwick, 2017). The influence of individual candidates is based on their competence in social media and how well they can create a synergy between social media and the older, more traditional media. This is mostly up to the candidates themselves because in party centred democracies, professional help is mostly provided for party leaders (Enjolras and Karlsen, 2016). However, as the Danish example suggests, one can expect politicians that are successful in this sense, “hybrid-media politicians”, to be younger than average, belong to different parities and come from a metropolitan area (Blanch-Östern et. al. 2017)

Research from Scandinavia has shown that use of social media by politicians is not high on a normal day, with spikes in usage mostly being connected to events in mainstream media and big political events. Usage will also pick up in the last few weeks before an election, especially when there is a political event in the mainstream media, reaching its peak on election day (Larsson, 2014). Politicians don’t seem to be using social media to keep in touch with their voters nor to get input. Their aim seems to be to preach to the masses when there is something they feel needs to be told, particularly when it pertains to gaining their vote (Larson, 2014).

When obtaining political information, social media is more important for younger voters whereas older voters use traditional media (Strandberg, 2013). The most influential users of Twitter do not consist of politicians holding top positions in their parties, but rather someone who is trying to make a name for themselves within the party. The average Twitter influential is male, young and rather centrally placed in his party (Enjolras and Karlsen, 2016). Social media has also been shown to be important in reaching citizens that are not exposed to campaign communication through other media as well as encouraging more voter participation in campaigns (Bor, 2014). Candidates do not only use social media to connect to voters but also to communicate to their own party in an attempt to gain more influence within it (Enjolras & Karlsen, 2016). Other research has shown that exposure to a Twitter account of a candidate results in higher political involvement, including greater voter participation, than only being exposed to an account of a party (Kruikemeier, et.al, 2016).

Most studies of the impact of social media on political communication and personalization are case studies and the trends found vary somewhat between countries and political systems. Research in Germany suggests that social media has had little impact on already low levels of personalization (Schweitzer, 2008). In Canada, high levels of personalization were recorded in the use of Twitter by party leaders, mostly focusing on what they were doing or were going to do (Small, 2010). In Norway, social media was shown to be a mode for personalized political communication (Enjolras and Karlsen, 2016). Another research compared personalization between presidential and parliamentary systems, with personalization being higher in the presidential system but also found it to be increasing in the parliamentary systems (Garzia, 2011). This is because of the growing impact of public perception of party leaders on voting decisions and because the media now focuses more on individual candidates rather than issues, and when they do talk about issues they are normally tied to a candidate and depend on his popularity (Garzia, 2011; McAllister,2007).

It is however important to note that the degree and nature of personalisation does not only vary between countries and political systems but also within countries and between territories and constituencies. As Chan (2018) has convincingly demonstrated, territory matters and e.g. in large constituencies local or regional issues are likely to become prominent and result in personalised politics by candidates, that are not necessarily in line with the more central party line (Chan, 2018).

The social media revolution is not something which only new parties are using to get listened to by voters, old parties have taken in social media as one of their communication tools. Research on the Icelandic hybrid media condition has shown that the emergence of new media has not had a great empowering effect on new or disadvantaged parties in Iceland (Guðmundsson, 2016). This in turn supports the normalization hypothesis, which says that the more established parties will have an advantage on social media due to having more of the resources needed to be successful (Schweitzer, 2008 and 2011; Lilleker et.al., 2011; Larson and Svenson, 2014; Larson, 2014). The new parties also look at the old media as being just as important as new media, although there is a degree of variation between parties (Guðmundsson, 2016). Other research has shown that parties in Iceland mostly think of social media as an advertising medium. A way to tell people what is going on in the cheapest, most efficient way or to tell voters what they can do to help the campaign, not to interact with voters or allow them to influence policy (Bergsson, 2014; Guðmundsson, 2014). Also important is the finding that communication officials in Icelandic parties tended to think that too much politics on Facebook would discourage voters’ attention, the point of Facebook being to post pictures and tell people where meetings would happen (Guðmundsson, 2014).

The Icelandic context

Iceland is an island in the North Atlantic with just under 350.000 inhabitants. Over two thirds of the population lives in the Southwest of the country in the capital Reykjavík and surrounding area. The Icelandic parliament, “Alþingi”, is unicameral and has 63 representatives from 6 multi member constituencies, elected using two tier proportional representation (d’Hondt). Of those members, 54 are elected through proportional results in each constituency while the other nine are divided proportionally to parties, who reach the 5% threshold, to make up the national results (Harðarson, 2008). The party system has been characterized by a four-party domination with no party outside the traditional four ever being elected for more than four terms. The Pirate party, which has served three terms, is the longest serving current party outside of the established four. The established four parties have combined received more than 85% of the votes in most elections since the beginning of the current party system in 1931. That proportion has however been significantly less in the last few elections. The traditional four parties are the conservatives (Independence party), which has been the largest party in every election except in 2009, the agrarian/centre party (Progressive Party), which has historically most often been the second biggest, the social democratic party (currently Social Democratic Alliance) and the socialist party (currently Left Greens). The parties on the left have periodically been restructured but it has always led to the same four types of parties. The norm in Iceland is majority government with no formal blocks, neither on the left nor right and the big four parties have all participated in a majority at some point with each other (Harðarson, 2008). Turnout in Icelandic elections is high compared to other countries, only once going below 80%, and voter volatility has also been relatively high, most often over 10% since 1971. The Icelandic system is a party-oriented system with high party discipline (Harðarson, 2017).

The Icelandic media system did not break party ties until around 1990 with all papers before that time having a direct or indirect link to a specific political party. The current media have all been accused of having some party orientation or working for the interests of their owners. Iceland has, compared to other countries, liberal rules for the ownership of media (Guðmundsson, 2016). This is most likely because of how hard it is to have many media companies in such a small market (Harðarson, 2008). The biggest player in the market is the state run public broadcaster RÚV which operates two TV channels (RÚV, RÚV2), two radio stations (Rás1, Rás2) and a webpage (ruv.is). Other big players are telecommunication- and other private companies and include Vodafone, Síminn and Árvakur. All in all, there are more than 20 TV channels in Iceland, over 30 radio stations and 2 daily national newspaper and several others.

The 2017 elections

The election on the 28th of October 2017 was an early election that came one day short of a year after the last one. It was the third early election in Iceland since 2008 and the second in a row. The election was caused by the Bright Future Party leaving a government coalition with the Independence Party and centre-right Reform Party. This was due to an alleged breach of confidence that had to do with an application to restore an honour program for ex-convicts wanting to get their criminal records cleaned. Issues relating to the program had been a hot topic on the news in the months leading up to the fall of the government, with a former child-molester getting his “honour” restored and then going on to repeat his offences. The alleged breach came with news that the prime ministers father had in a different case in the past signed a recommendation letter for a convicted child molester, something the prime minister knew about for two months without telling his coalition partners (Harðarson & Önnudóttir, 2017). After the 2016 elections it took more than 2 months to form a government, so instead of trying to form a new majority, Prime Minister Benediktsson dissolved the parliament on the 18th of September and announced new elections in six weeks’ time (Harðarson, 2017). Despite the moral reasons behind the early election, the campaign was conventional, focusing on issues such as health care, economic stability, welfare and taxes (Harðarson & Önnudóttir, 2017). Turnout in the election was 81,2%, just higher than the record low of 79,2% from 2016. Eleven parties ran in the elections, 9 ran in all constituencies, and 8 of them got candidates elected into parliament. The outgoing majority parties all lost seats in the parliament, with the Bright Future dropping out of parliament with only 1,2% (-6% from the last election). This was the fourth consecutive majority to suffer a loss of more than 10%, with only 7 out of 22 coalitions since the 1931 elections gaining votes. The old big four parties only obtained 64,9% of the votes a slight improvement from the 62,1% they obtained in 2016 but still a historic low (Harðarson, 2017). The fact that the elections were held on such short notice may have impacted the focus on social media.

Research questions

The aim of this paper is to see if social media platforms are mainly a vehicle for personalized politics in Iceland, a historically party centred system. While news values of traditional media and their programming and editorial structure tends to put focus on party leaders and party spokesmen, the more fragmented and horizontal structure of network media logics of social media platforms gives space to individual candidates. Thus, the aim is to find out to what extent political communication in social media is party-political and to what extent is focuses on the candidates themselves. Clearly, in a hybrid media system, there is no definite criteria on the proportion of certain type of content to determine whether or not a platform is predominantly a tool for personalization, but it can be suggested that if one half or more of the content is of a personal nature, the platform can be considered a vehicle for personalized politics. This research subject will be approached through posing four interrelated research questions that deal with the type of content in social media platforms before the 2017 parliamentary elections in Iceland. Also, the difference between candidates and parties as well as individual social media platforms will be explored.

RQ1. Are social media a platform for personalized politics in Iceland? This basic question aims to establish through measurements what kind of content is posted on social media platforms.

RQ2. Is there a variance in the social media use of candidates? It is unlikely that all parliamentary candidates use social media in the same way and it is of major importance to draw out the differences with respect to variables such as the party of candidates, geographical area, gender and whether a candidate was elected or not.

RQ3. Is there a difference between the ways in which major social media platforms are used? This is an important question as while many studies have been done on the role and use of different social media all over the world, e.g. Twitter (Jungherr, 2016), very few if any have sought to establish the difference in use of individual social media platforms.

RQ4. Is social media use mainly orchestrated from central party organizations to boost party centred communication or a united party line? Through this question an insight should be gained into the role of party organizations in the social media use of candidates.

Methods

The four research questions will be dealt with in two ways. Three of the four questions will mainly be answered by way of content analysis of the posts of parties and candidates on social media in the run-up to the elections. One question, the one on the relations between the central party organization and the autonomy of individual candidates will be explored through half – standardized interviews with party officials from five of the nine parties that ran in all six constituencies.

Content analysis

The content analysis was done in the last two weeks before the election on the 28th of October 2017 starting on the 14th and ending on the 27th of October. Only the 9 parties that ran in all 6 constituencies were followed, with 8 of them eventually being elected to parliament. The top two candidates on the party lists for each party in each constituency were followed, as well as the official social media accounts of the parties on Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat. Each post was coded into one of three categories.

Category 1, non-political personal: the posts were non-political and mostly consisted of the candidates telling people where they had been or where they were going, as well as pictures and posts saying how lovely some place or people were.

Category 2, political personal: consisted of posts where the candidate was defining his own policies, defined by phrases such as “I believe”, “my view is” and “if elected I will” etc.

Category 3, political non-personal: This category consisted of party policies, with statements such as “my party believes”, “our party wants to…”, and so forth.

To answer RQ2 the data was analysed in the light of 8 variables. These were: gender, constituency, leadership position, party, if a candidate was elected or not, if the candidate was from an old or a new party, how active candidates were on social media, and if the posts came from a party account or a candidate account.

Facebook was the dominant medium with 97% of candidates and all 9 parties posting on there at least once during the two weeks analysed. Snapchat was barely used, with only two parties and two candidates using the medium during the campaign. Twitter usage varied greatly between parties, ranging from candidates of the Bright Future Party posting on average 28 times per day to not a single tweet from a candidate from the Peoples- or Centre parties.

Interviews

The half-standardized interviews focused on party officials mainly responsible for the social media communication strategies of the respective parties. The purpose of the interviews was to deepen information acquired through the content analysis and in particular to establish the role of the central party organizations in the social media use of candidates and in dictating a party line. However, the interviews were only half- standardized and thus not confined to this topic, allowing the interviewees to initiate and offer points that they thought to be important. The interviews were both conducted face to face and through telephone. They were taped, typed up, coded and analysed into themes. All in all, there were five interviews with officials from five different parties that stood in all six constituencies.

Results

There now follows a discussion of the results, starting with results of the content analysis in light of the three relevant research questions, on the content and variation in use of different social media platforms. Then the interviews will be analysed to add understanding about the research question on the relations of central party organizations and candidates and the role of social media in the overall communication strategy of the parties.

Content analysis

The results from the content analysis are primarily based on Facebook data because of the lack of posts by politicians on Twitter and Snapchat. It should however be noted that 84,3% of the coded communication on Snapchat falls into the non-political personal category (category 1), but the significance of this is limited because of the lack of posts and posters (only 108 total posts). Twitter is also too small in the research to be convincingly important but a general comparison between Twitter and Facebook will however be introduced below.

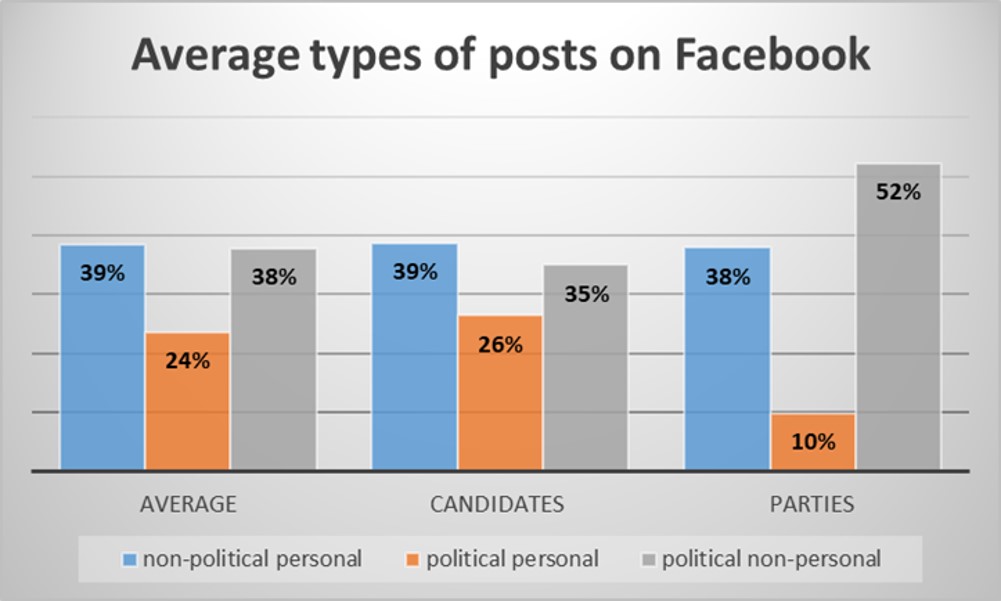

Personalized vs. party accounts: Figure 1 provides a positive answer to the first research question, suggesting that social media (Facebook) are dominantly personalized tools in Icelandic political communication. When the average of all posts posted on Facebook during the campaign is considered, we find that personal posts, both political personal and non-political personal posts constitute some two- thirds of the whole (63%). The difference between the types of posts from parties on the one hand and candidates on the other is striking. Parties post to a much larger extent political posts (52%) than the candidates do (35%). While communication by the candidates themselves can be said to be dominantly personalized this is not so for the official party communication although it is only just under the 50% mark.

Figure 1 The average communication on Facebook by parties, candidates and the general average.

Variance in social media use: Next, we turn to an examination of the variance in the use of social media platforms which was the subject of the second research question. Specifically, we shall look at the following variables: party leaders vs. other candidates; differences between parties; differences between constituencies; differences between metropolitan areas and the regions; differences between men and women; and finally difference in the posts of candidates that got elected and those that did not.

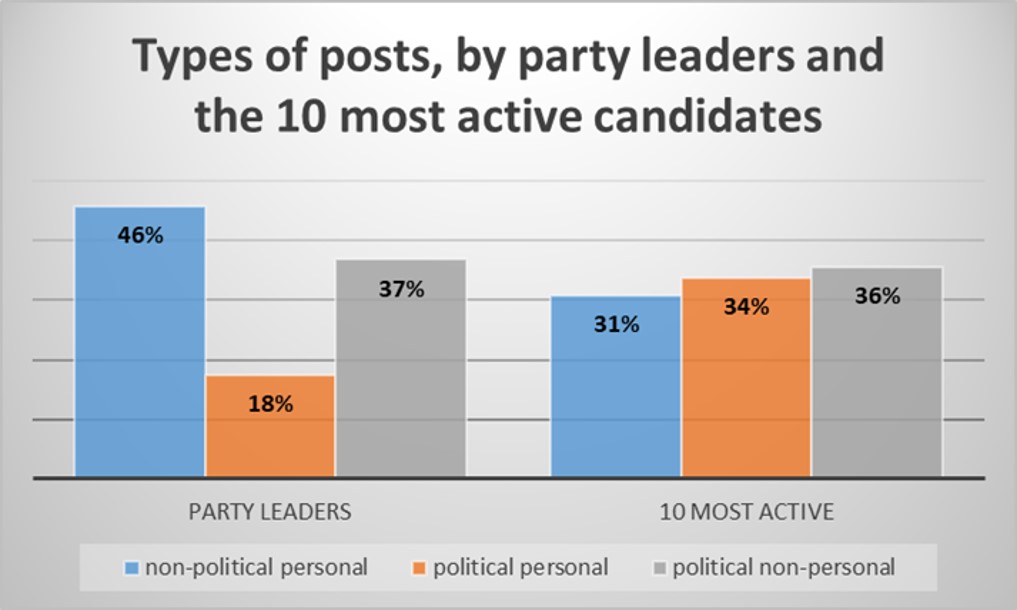

Party leaders: Figure 2 shows a comparison between the 9 party leaders and the 10 most active candidates on social media. Personal posts from both groups are above the 50% mark, with both party leaders and the 10 most active candidates at 64%. Despite the amount of personal posts being similar for both these categories there are a lot of internal differences, the 10 most active candidates have similar amounts of communication from all categories, therefore they differ from the average by having more personal political and less personal non-political (category 2 and category 1). Active posters therefore seem to post more of their own political thoughts than the average candidate and less non-political material. Some 46% of the posts made by party leaders fell into category 1 (non-political personal communication) but at the same time they only have 18% from category 2, political personal communication. This can probably be explained by the leader representing the party and therefore the party´s policies are also personal policies. Furthermore, leaders receive more attention in traditional media and do not need to profile themselves politically on social media to the same extent as non-leaders.

Figure 2 The average of the type of posts on Facebook from the party leaders and the most active candidates.

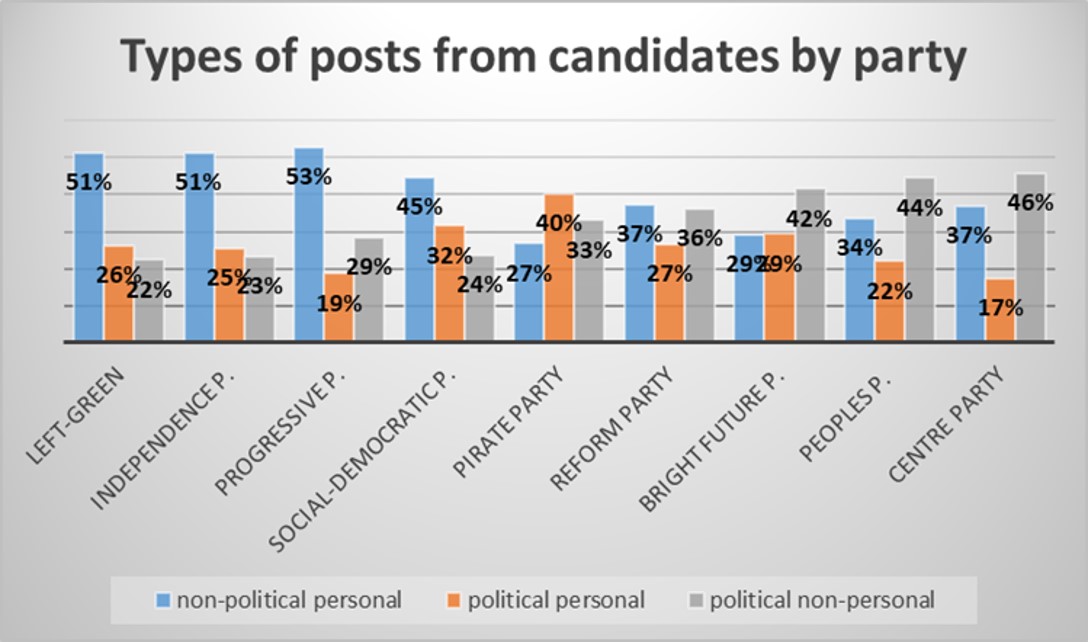

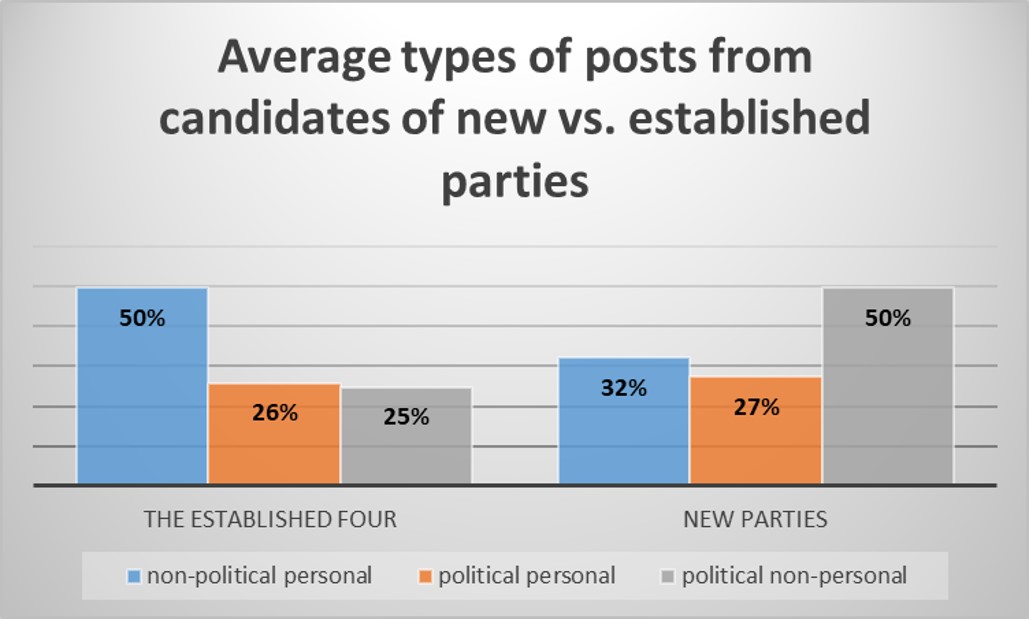

Party differences: The results regarding the difference between parties show quite a clear distinction between the new parties and the old traditional parties. Although the social media communication can be said to be dominantly personal (category 1+2) for all the parties, the established four had by far the highest number of personal posts, or an average of 76%, while the average of personal posts was 59% with new parties. Candidates from three of the four traditional parties, excluding the Social democrats, had more than 50% of their social media communication coded as non-political personal, while that average was only 32% for the new parties (Figures 3 and 4).

It can therefore be suggested that the newer parties look at social media as a platform to introduce their policies to voters and that their candidates look at these media more as a political tool than do the candidates from the big four. Both the parties that were running for the first time (Centre party and People’s party) had a very high proportion of party-political communication on social media. Only one other party, the Bright Future had more than 40% of its communication from the political non-personal category. The big parties use social media more to connect with voters in a personal way and show the human side of their candidates.

Figure 3 The average of the type of posts from candidates by party.

Figure 4 A comparison of the type of posts by candidates of the big four parties and the new parties on Facebook.

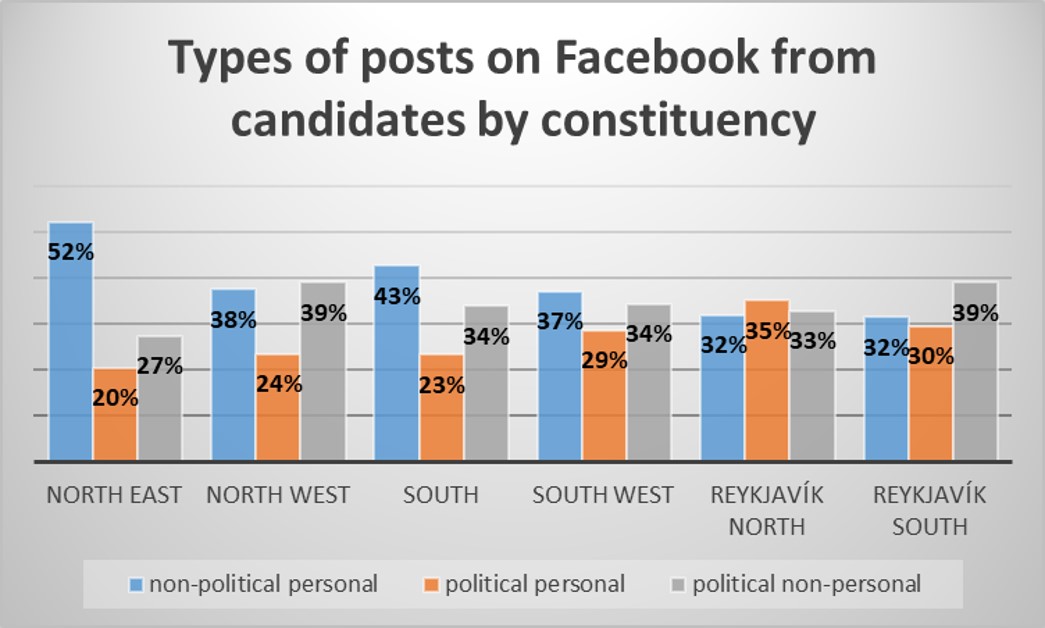

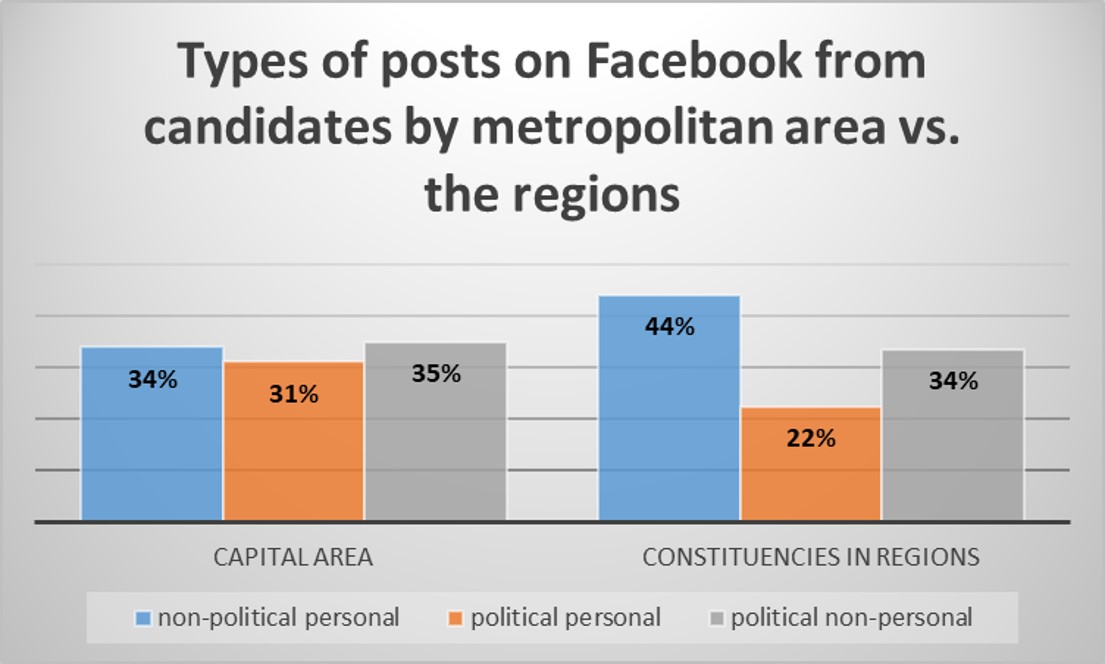

Difference between constituencies

There is a big difference between the social media use of candidates from different constituencies. Candidates in all constituencies were found to have personalized posts, although there was some difference, especially between the capital area and the countryside constituencies. Comparing the 3 constituencies that make up the capital area (Reykjavík-North, Reykjavík-South and South-West) against the three that make up the regions (North-West, North-East and South) it can be seen that both are dominantly personalized. However, an interesting difference lies in how much more emphasis candidates from the regions seem to put on non-political personal communication versus their own politics and the politics of the party. The fact that they emphasise category 1 (non- political personal) communication more than candidates in the metropolitan constituencies is potentially due to the sheer size of their constituencies, the three constituencies outside of the metropolitan area cover vast territories. Here Chan´s (2018) point on the importance of territory probably kicks in. Purley practical reasons are also at play, as many posts are informing people where the candidates are or will be. The North-East clearly stands out with the value for category 1 by far the highest and party-political communication the lowest.

Figure 5 A comparison of candidate communication on Facebook depending on which constituency they are from.

Figure 6 The difference in social media communication between the capital area and the countryside constituencies, on Facebook.

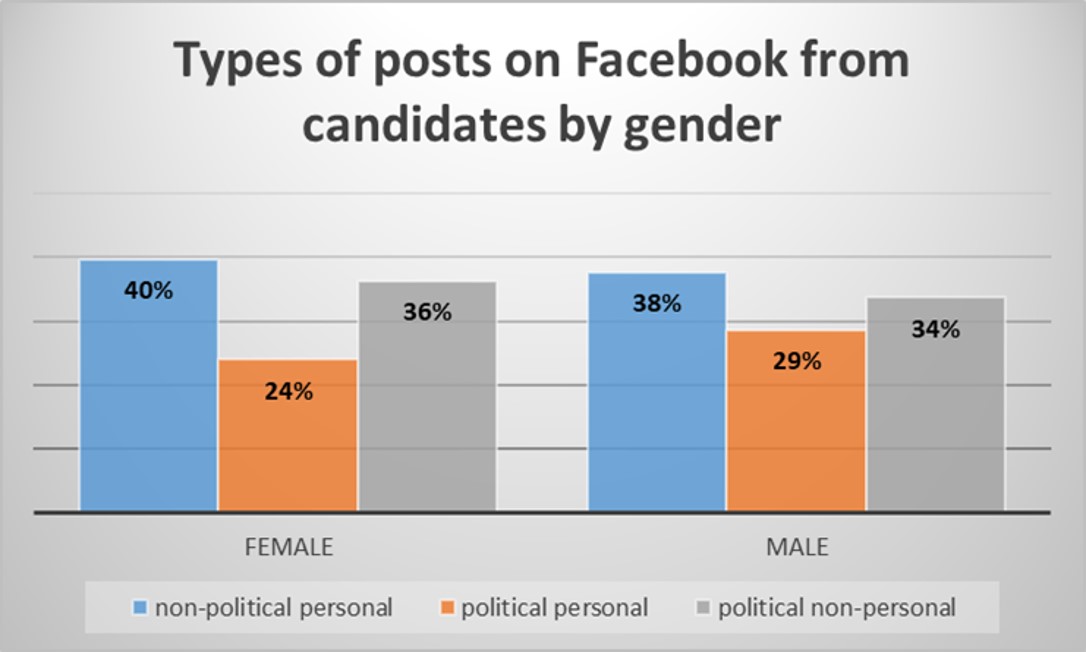

Gender differences: Gender does not seem to be a significant variable in determining what candidates post on social media. Both males and females post dominantly personal posts. In all categories the difference seems only marginal. Neither men nor women being more dominant in one category than another.

Figure 7 Differences between the communication of female and male candidates’ communication on Facebook.

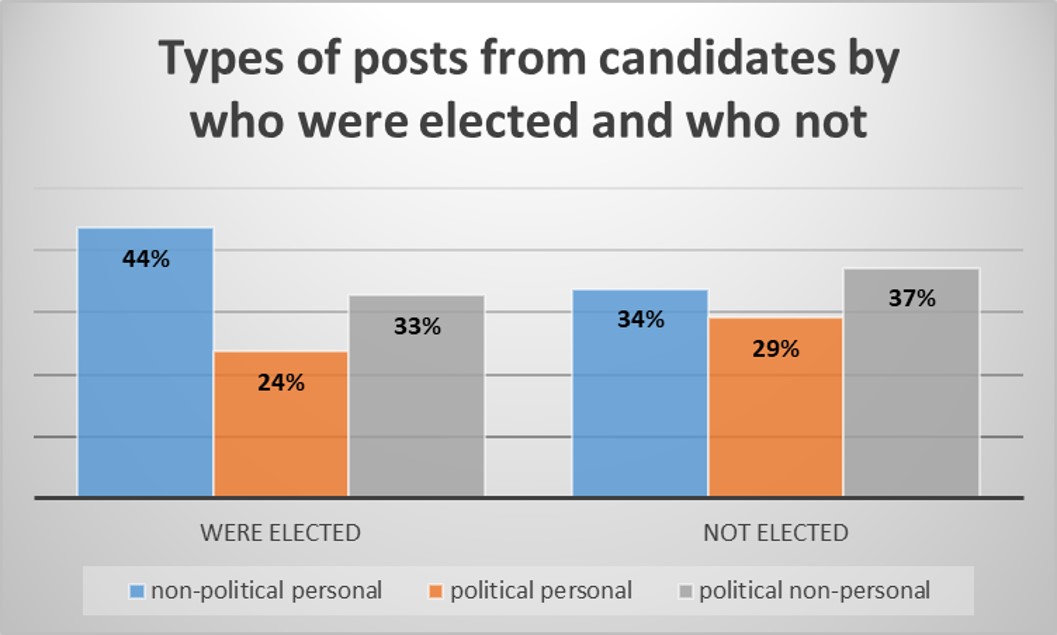

Elected candidates vs those who didn’t get elected: Finally, it is hard to draw conclusions from the posts of those who did get elected and the ones that did not. The nature of the Icelandic political system, with party lists and proportional representation as well as the different size and following of the parties call for a careful interpretation. But the results indicate that it is not necessarily good for politicians to be very political – at least not on social media! Those who got elected are much more personalized and non-political than the candidates who did not get elected. The candidates who failed to get elected also had slightly more communication coded as political non-personal.

Figure 8 The difference between the Facebook communication of those candidates who did get elected and those who did not.

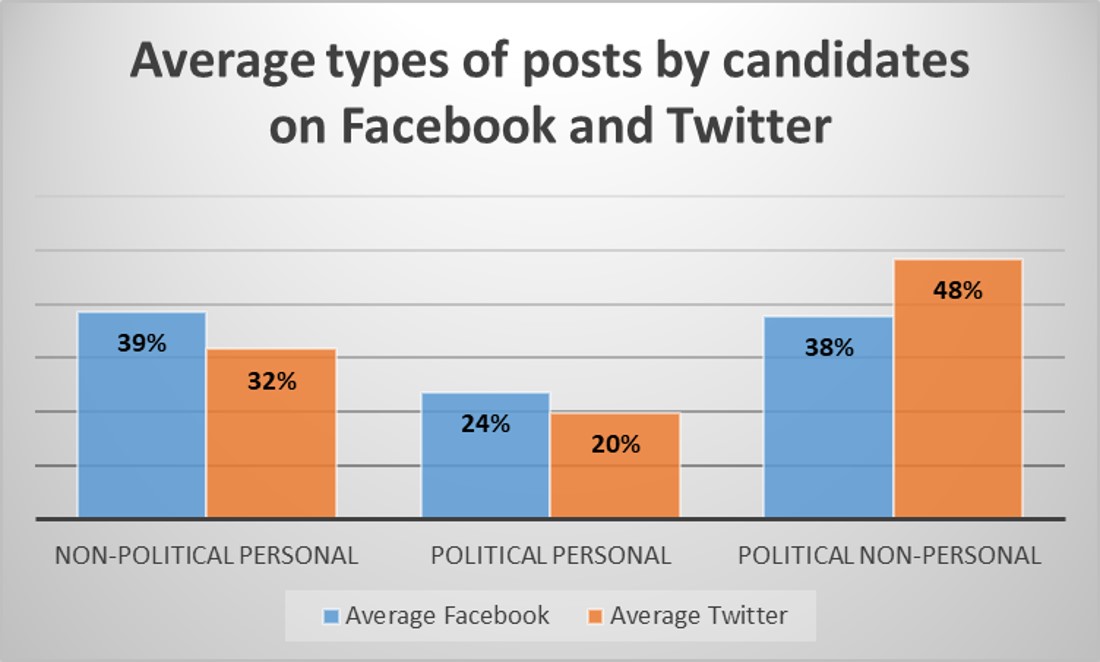

Facebook vs.Twitter: As mentioned above the results are based on the Facebook part of the research project because of the lack of activity on Twitter and Snapchat. RQ3 however asks about the difference between the ways in which the major social media platforms are used. As pointed out earlier, Snapchat was not much used in the 2017 campaign and to the extent it was used its use fell into the category of non-political personal communication. Twitter on the other hand, is a more popular platform with politicians and it is interesting to compare the results of Facebook to those of Twitter. Both gateways can be said to be personalized, although Twitter is only just over the one-half line, with 52% of posts on average coded as personal. Twitter is much more political than Facebook, and with 68% of the Twitter posts coded in two political categories, Twitter can be said to be dominantly political. But with only 42% of its posts coded as personal it is much less personalized than Facebook. Candidates use Twitter as a political medium much more so than Facebook, that is to say, those candidates who have a Twitter account in the first place and are actively using it.

Figure 9 There is a clear difference between the two social media platforms as Facebook is more personal than Twitter which has almost one-half of its posts “political non-personal”.

Interviews

When analysing the interviews, five main themes came up that were considered to have impact on how the parties and candidates acted on social media. The analyses are mostly based on Facebook which all interviewees perceived as the most important social medium for political communication in Iceland, because as one interviewee said, “that’s where the people are”. The themes are the following:

- Candidate freedom and external professional help: The extent to which the candidates control what they post on social media and how much help is available to them.

- The effects of the short run-up to the elections: How the fact that parties only had 6 weeks to plan for the election changed their focus on social media and the content that they posted there.

- Negative ads on YouTube: How did reacting to negative ads change the focus on social media?

- Targeting and voter data: The extent to which the parties tried targeting groups on social media and what voter data they used to inform those decisions.

- The perceived personalization of social media: What was, according to the party officials, the main theme of the party communication during the election.

Candidate freedom and external professional help: All interviewees said that there had been some professional help for candidates in how to use social media but that it had mostly been in teaching candidates how to use social media and explaining what kind of material worked best, without being directly instructed what to put on social media or how to present it. Although they all added that it was very important that everyone in the party was talking about the same thing, sometimes there was a need to intervene when someone was drifting too far off the party line.

The effects of the short run-up to the elections: The 2017 elections were held with only six weeks’ notice, although normally party officials have years to prepare for an election. The general agreement was that such a short notice made it harder to put out quality material and be ready for the social media conversation and they all would have wanted more time to work on the content. One interviewee said:

“It had an impact as we didn’t have any material (to post on social media) and sometimes we didn’t have the time to create it which made things more difficult.”

There was also a general agreement that the role of social media had increased due to the lack of time for making material for other media, or to plan as many meetings as would have been in a normal election year. In the words of one official:

“The difference between the elections of 2016 and 2017 is enormous. All the power went into social media, much more than it would have been if we would have had a longer notice.”

Negative ads on YouTube: The 2017 elections were the first in Icelandic history to have a significant number of negative advertisements. These mainly came from anonymous sources or independent actors not directly or openly connected with a political party. There were ads against every party, but the Left-Greens and Social Democratic Alliance took most of the heat. The officials from both of those parties mentioned this as the biggest challenge they faced in the 2017 elections. They said a lot of work went into trying to answer those on social media, and both thought they had mostly failed in responding.

Targeting and voter data: The focus on how parties use voter data and how much they try to target voters through social media has been very prevalent in all social media research since the Obama election of 2008 (Chadwick, 2017). There was a wide range in how much parties tried to target the audience for their messages ranging from the Left-Greens only targeting by location in preparation for regional meetings to the Social Democrats, Reform party and Centre party saying they tried to target most things that was sent out in the name of the party. They all used some form of voter research in deciding what to put out and who to target, for example targeting labour workers for labour issues and women with equality measures.

The perceived personalization of social media: One theme that came up in the interviews was if the party had focused more on presenting political issues or candidates. The Social Democrats, Reform party and Centre party all said they focused more on policy issues while the Independence party had focused more on interacting with voters. But the Left-Greens focused more on the candidates or as their official said: “Our emphasis, although we always had policy in the bits, was on Katrín [Jakobsdóttir]. It (the focus) was on the candidates and mostly on Katrín.”

Themes summary: Viewing these five themes considering RQ4 it becomes evident that the candidates have considerable autonomy in their advocacy and in pursuing personalized political communication. The interference of the central party in the electioneering of the ordinary candidates is mainly of a technical nature, providing training and skill in the operation of social media platforms and providing some targeting information, to help candidates to be more effective in their posts. Furthermore, the complaints that preparation time was short to produce material for the campaign, points to an important role of the central party organisations in providing stuff for candidates to post and share, with their own personal additions and comments. Other concerns that emerge in the interviews support the view that in European parliamentary systems the ordinary candidates are pretty much on their own while the central party organizations focus more on party leaders (Enjolras & Karlsen,2016; Blach-Örsten, et.al. 2017).

Discussion

The findings presented in this paper suggest that social media is indeed a vehicle for personalisation in politics in Iceland. This is an addition to other forces that have contributed to an increase in personalisation, such as the decline in partisan attachments and general political dealignment in Iceland in recent decades and the news value focus of traditional media on personalities. In this sense it can be argued that Iceland is threading the same path as other parliamentary democracies. However, this might be of special consequence in Iceland because dealignment and distrust in the political system escalated after the financial meltdown in 2008 and the massive shock and sense of political corruption that followed and exploded in the “pots and pan” revolution (Bernburg, 2016). At the same time there is considerable distrust in traditional media and its professional integrity (Guðmundsson, 2016). This makes the influence of social media even greater than in neighbouring countries where traditional media is stronger and has a richer professional heritage. As the trustworthiness of institutions, parties and media has declined, the importance of the trustworthiness of personalities increases and these personalities express themselves largely through networked logic of social media platforms. This expression can e.g. take the form of new parties or candidates offering their services, claiming to be more trustworthy than existing politicians. This expression can also appear within parties as a candidate in quest of more trust seeks to distance himself from a party which has lost trust, or at least to demonstrate some independence from it. This line of reasoning would indeed rhyme with party-splits and the increased number of parties standing in elections in Iceland since 2013. Individual candidates seem to have considerable autonomy vis-á-vis the central party organisations in the way in which they use social media – with limits though – for their own personalised political campaigns.

Another important element is highlighted in the findings connected to the relations between the central party structures on the one hand and the candidates on the other. It seems that elements of “presidentialism” which has been highlighted in the literature (e.g. Lobo, 2018) can be seen in the close cooperation between the central party organisations and the party leaders. The similar nature of the posts by the party organisations and the party leaders suggests that the leaders might be controlling the agenda of the party rather than presenting it, which indeed is a form of personalisation. And the variance in the forms of personalisation and the rather slack central control is still furthered by the territorial difference which can be seen to be in line with findings elsewhere (Chan, 2018).

Earlier research on media use by candidates in Iceland suggested that new and small parties could not claim an advantage over older parties on the grounds of new media gateways such as social media, even though these media were readily available and inexpensive, simply because older and established parties also use these media (Guðmundsson, 2016). This study adds an important point to that discussion, namely that new and small parties seem to use social media in a different manner than the more established parties. While the established four tend to be more personalised on social media the new and small parties seek to use these platforms to spread political messages, possibly because of lack of other means of communication.

Thus, the findings in many ways compliment findings from elsewhere and the general literature, but the Icelandic case study also adds to and sharpens the understanding of personalisation in general. One last point should be mentioned as it is of major importance, not only for further study of social media and politics in Iceland but for such research in general. There is clearly an important difference between the ways in which politicians use social media platforms. Personalised politics are clearly more practised on Facebook than Twitter. Indeed, Twitter is quite political, which needs not come as a surprise as it is in many ways an elite medium for politicians and journalists and has been widely studied as such (Jungherr, 2016). In light of the finding presented above is becomes precarious to talk of social media as a single entity with the same general characteristics. That would clearly be an oversimplification of the situation in Iceland and the role of Facebook on the one hand and Twitter on the other.

References

Bernburg, J. G. (2016). Economic Crisis and Mass Protest; The Pots and Pans Revolution in Iceland. Oxon: Routledge.

Bergsson, B. Th. (2014). Political parties and Facebook: A study of Icelandic political parties and their social media usage. Stjórnmál og stjórnsýsla 10(2), 339-365. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.13177/irpa.a.2016.12.1.3

Blach-Ørsten, M.; Eberholst, M. K.; Burkal, R. (2017). From hybrid-media system to hybrid-media politicians: Danish politicians and their cross media presence in the 2015 national election campaign. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 14(4), 334-347. DOI: 10.1080/19331681.2017.1369917

Bor, S.E. (2014). Using social network sites to improve communication between political campaigns and citizens in the 2012 Election. In American Behavioral Scientist. 58(9), 1195–1213. DOI: 10.1177/0002764213490698

Chadwick, Andrew. (2013). The Hybrid Media System. Politics and Power. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system. Politics and Power (Second Edition). New York. Oxford University Press.

Chan, H.Y. (2018) The territoriality of personalization: New avenues for decentralized personalization in multi-level Western Europe. Regional & Federal Studies. 28:2, 107-123, DOI: 10.1080/13597566.2017.1411906

Enjolras, B., & Karlsen, R. (2016). Styles of social media campaigning and influence in a hybrid political communication system: Linking candidate survey data with Twitter data. The International Journal of Press/Politics. 21(3) 338–357. Doi: 10.1177/1940161216645335

Gallup. (2017, 16th of November). Samfélagsmiðlamæling Gallup. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.is/frettir/samfelagsmidlamaeling/

Garzia, D. (2011). The personalization of politics in Western democracies: Causes andconsequences on leader–follower relationships. The Leadership Quarterly. 2011 (22)697–709. Doi: /10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.010

Garzia, D., Ferreira da Silva, F., & De Angelis, A. (2018). Partisan Dealignment and the Personalization of Politics in West European Parliamentary Democracies, 1961-2016. UC Irvine: Center for the Study of Democracy. Retrieved from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8r7500zq

Guðmundsson, B. (2014). New realities of political communications in Iceland and Norway. Nordicum – Mediterraneum 9 (1). Retrieved from http://www.nome.unak.is/nm- marzo-2012/ volume-9-no-1-2014/60-article/456-new-realities-of-political-communications- in-iceland-andnorway

Harðarson, O.Þ (2008). “Media and politics in Iceland“.In J.Strömbäck, M.Örsten, & T.Aalberg, (Ed.) Communication Politics: Political communication in the Nordic Countries. Gothenburg: Nordicom

Harðarson, Ó.Þ. (2016). Icelandic Althingi election 2017: One more government defeat – and a party system in a continuing flux. Retrieved 15th of December 2017 from: https://whogoverns.eu/iceland-2016-major-changes-but-not-a-revolution/

Harðarson, Ó.Þ., & Önnudóttir, E.H. (2017, 11th of December). Iceland 2017: A new government from left to right. Retrieved from https://whogoverns.eu/iceland-2017-a-new- government-from-left-to-right/

Jóhannsson, J.P. (2016) 40 prósent vilja Katrínu Jakobsdóttur sem forsætisráðherra. Stundin. Retrieved 7th August 2018 from: https://stundin.is/frett/40-prosent-vilja-katrinu-sem-forsaetisradherra/

Jungherr, A. (2016). Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 13(1), 72–91.

Klinger, U. and Svenson, J. (2014). “The emergence of network media logic in political communication: A theoretical approach”, New Media & Society. Online first, February 19. Available at: http://nms.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/02/18/1461444814522952

Klinger, U.; Svensson, J. (2018). The end of media logics? On algorithms and agency. New Media & Society 1-18 Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444818779750

Kruikemeier, S., Noort, G.V., Vliegenthart, R., & Vreese, C.H. (2016). The relationship between online campaigning and political involvement. Online Information Review 40 (5), 673-694. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-11-2015-0346

Larsson, A.O. (2014). Online, all the time? A quantitative assessment of the permanent campaign on Facebook. New Media & Society. 18(2), 274–292. Doi:10.1177/1461444814538798

Larsson, A. O. and Svensson, J. (2014). “Politicians online – identifying current research opportunities”, First Monday, 19(4). Available at: http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4897/3874

Lilleker, D. G., Koc-Michalska, K., Schweitzer, E. J., Jacunski, M., Jackson, N., and Vedel, T. (2011). “Informing, engaging, mobilizing or interacting: Searching for a European model of web campaigning.” European Journal of Communication, 26(3), 195 – 213.

Larsson, A.O. & Moe, H. (2014). Triumph of the Underdogs? Comparing twitter use by political actors during two Norwegian election campaigns. Sage Open. First Published December 8, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014559015

Lobo, M. (2018). Personality Goes a Long Way. Government and Opposition, 53(1), 159-179. doi:10.1017/gov.2017.15

Magnússon, H. D. (2016) Katrín nýtur stuðnings flestra. Morgunblaðið. Retrieved 7th of August 2018 from: https://www.mbl.is/frettir/kosning/2017/09/25/katrin_nytur_studnings_flestra/

Meeks, L. (2017). Getting personal: Effects of Twitter personalization on candidate evaluations. Politics & Gender. 13(1), 1–25. doi:10.1017/S1743923X16000696

McAllister, I. (2007). The personalization of politics. In Dalton and Klingemann (editors) Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior (571-588) Oxford: University press

Schweitzer, E.J. (2008). Innovation or Normalization in e-campaigning? a longitudinal content and structural analysis of German party websites in the 2002 and 2005 national elections. In European Journal of Communication 23(4) pp. 449 – 470. Doi: [10.1177/0267323108096994

Strandberg, K. (2013). A social media revolution or just a case of history repeating itself? The use of social media in the 2011 Finnish parliamentary elections. In new media & society 15(8) 1329–1347. Doi: 10.1177/1461444812470612

Small, T. A. (2010). Canadian politics in 140 characters: Party politics in the Twitterverse. In the Canadian parliamentary review. Retrieved from http://www.revparl.ca/33/3/33n3_10e_Small.pdf c

Statista. (2018, no date). Active social network penetration in selected countries as of January 2018. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/282846/regular-soial- networking-usage-penetration-worldwide-by-country/

Schweitzer, E. J. (2008). “Innovation or Normalization in E-campaigning? A longitudinal content and structural analysis of German party websites in the 2002 and 2005 national elections”, European Journal of Communication 23(4), 310 – 327.

Schweitzer, E. J. (2011). “Normalization 2.0: A longitudinal analysis of German online campaigns in national elections 2002–9”, European Journal of Communication 26(4), 449-470.