Introduction

This article discusses the concept of integration as it appears in a select body of social policy documents in Norway, and relates it to the Norwegian model of welfare. In Norway as well as other European countries, the concept of integration has been an issue of debate over the last 30 years. Integration is a contested term because it is difficult to define and operationalize. It is used politically from so many shifting positions, and it highlights underlying questions on national boundaries, national identities, and questions concerning distribution of national welfare.

The concept of integration is most often associated with immigration and inclusion of new citizens. The EU defines integration as “a two-way process based on mutual rights and corresponding obligations of legally resident third-country nationals and the host society which provides for full participation of the immigrant. (Collett, 2008) Anthony Giddens in his book Europe in the Global Age, describes how Europe in the age of globalisation has become vulnerable, due to unemployment, financial crisis, changing demography, environmental challenges and substantial immigration and demands for adaptation to increased cultural diversity (Giddens, 2007). Policies developed to handle immigration and the cultural diversity associated with it, are often referred to by the term integration. As the EU definition states, integration involve EU host countries allowing immigrants to fully participate in society. This article focuses on how this policy has been defined and implemented in Norway.

Frame analysis

Integration has for a long period of time been a policy area in Norway, and this policy area has been developed and chronicled through various documents and reports. Policy here includes government papers, visions, programmes, plans for action, and modes of implementation. My interest in this article is to analyse the development of understandings and shifting positions behind integration politics. Party politics and public debates are particularly influential to this policy, but they will not feature directly in the analysis.

To investigate such understandings and shifting positions Carol Bacchi asks “What’s the problem represented to be?” (Bacchi, 2009). Policy is here defined as “a problematizing activity”. In defining the problem, some aspects are included and illuminated, while other dimensions are excluded in order to avoid complexity. In Bacchi’s analysis one is not searching for real problems that are meant to be solved, but one is rather searching for contesting views of the problems and how they are defined. This means identifying and evaluating the problem by questioning the taken for granted assumptions within the particular policy field. It further involves explicating the ways in which problems are described, how reasons for problems are analysed and what the implications of these problems involves (Lotherington, 2002). The problem representations can be stated along material lines (through access to and distribution of resources) or along discursive lines (through the attribution of legal and/or cultural norms and interpretations or through the use and legitimation of violence (Verloo & Lombardo, 2007).

Jørgensen and Thomsen suggest the use of critical frame analysis (Jørgensen & Thomsen, 2012) when analyzing social policy. Frame analysis is a concept originated in the work of Erving Goffman, who saw reality as a “schema for interpretation” – where framing refers to the actors interpretations of reality in actual situations (Goffman, 1974). In frame analysis one assumes the existence of multiple interpretations of the discussed problem, and the task is to explore the implicit and explicit understandings involved. Verloo and Lombardo defines a policy frame as “an organizing principle that transforms fragmentary or incidental information into a structured and meaningful problem, in which a solution is implicitly or explicitly included” (Verloo & Lombardo, 2007: 20). The theoretical notions of framing, are also associated with social movement theory, building on the works of Benford and Snow:

Framing describes an active procedural phenomenon that implies agency and contention at the level of reality construction…. Thereby, the political process can be characterized as a contest between different frames regarding the right to interpret an issue or social problem. (Benford & Snow, 2000: 614)

If policy is seen as a contest between frames, it is this contest or “conceptualization of frames” that becomes interesting for analysis. Some of these frames then become frames for collective action, and “frames tasks” for the policies to follow. If we say for instance that integration has to do with income redistribution, it might be the financial dimension of the problem that is addressed. By contrast, if integration is defined as a problem of cultural difference, we might focus on ways to incorporate the differences, or adapt to differences involved. Benford and Snow suggest that these tasks are framed in three particular ways, and they are followed by specific problem-setting stories. (Benford & Snow, 2000: 615)

The table below delineates Benford and Snow’s concepts of framing.

|

Framing tasks

|

Diagnostic framing

|

What is the problem?

How is it defined?

|

|

Prognostic framing

|

How do we solve the problem?

|

|

Motivational framing

|

How do we argue for our definitions and solutions – ideology

|

|

Problem-setting stories

|

Specific representations

|

They way problems are told, presented and given meaning

|

(Benford & Snow, 2000: 616)

If we view the problem of integration for example as an unemployment problem where specific groups are outside the labour market, our diagnostic framing will focus on unemployment generally. These diagnostics could also be more specific, by suggesting that unemployment is related to demands for particular competences, to issues of discrimination or racism, or to structural crisis in the economy. The way we think about solutions to this unemployment problem, will represent our prognostic framing. The implementation of the prognostic framing will depend on the way the problem is understood. If discrimination is defined as the source of the problem, the prognostic framing would center on legal initiatives rather than business support programs. The motivational framing in turn will be necessary to motivate for and pave the way for relevant implementations, for instance through legislation and political decisions. During the 1990’s there was a strong focus on integration politics in Norway. Within this decade there was a deep economic recession, with high unemployment especially among foreigners. According to the media, may have been related to cultural difference, but this diagnostic frame did not solve the problem of the structural crisis. Problem-setting-stories might be put forward when the media present the problem in specific ways, for instance the story of an immigrant who had been beaten up at his work-place would diagnose the problem as one caused by racism or discrimination.

Verloo and Lombardo suggest to incorporate the dimensions of “location” and “mechanisms” into the analysis of frames. (Verloo and Lombardo, 2007) This means that we have to find “locations” where integration actually is supposed to take place, and find out which “mechanisms” in society help to facilitate or impede integration. If as in the Norwegian case, integration is associated with welfare politics, then welfare services are a kind of location. The legal system behind these services is part of the mechanisms relevant for this inquiry. These two dimensions together can shape the context behind what we are studying.

Foucault suggests an understanding of context that embraces history and society as something broader than both the individual hermeneutical interpretation of society on one hand, and the structural determinants on the other hand (Foucault, 2012). Context appears in this sense as a shifting environment constructed through the lines of history, into collective representations:

In a Foucaultian frame, the condition of temporary society cannot be understood by examining the negotiated meanings of social agents, nor can it be found within the broader field of social relations. Rather a history of ungoverned practices and knowledge relations brings subjects and the knowledge that constitutes them into play. Foucault called the methodological approach that takes history of these relations as its object of investigation “geneaology”. (Bastalich, 2009: 5)

Bastalichs point is to show that Foucaults work on genealogy shifts away from persons producing meaning – as in hermeneutics – and points to the role of historical practices and discourse in producing subjectivity and meaning. In this way Foucault presents an important epistemological and ethical basis for knowledge, and this basis deserves attention on its own terms. According to Bastalich, this does not have to do with a search for “authentic voices” and “the majestic performance of the sovereign subjects.” Society is constructed from established “positions of knowledge” which are collective, continuous and stable, as opposed to individual interpretations. In this Foucault also focuses on the role of Government, and points to the role of the State as a disciplinary force that produces knowledge in society, – a knowledge that “defines” the population, and the represented problems connected to the population.

Genealogy offers socially relevant descriptions of the interrelations of past practice and knowledge that enable reflection on our current condition. Their value lies in their ability to open the field of practice by throwing current rules into doubt. (Bastalich, 2009: 5)

When applying Foucault’s concept of genealogy to this policy analysis, the “frames” we are investigating cannot be understood in isolation from time and space. Rather they must be understood in relation to each other as “positions of knowledge” that have been constructed and developed over time (Foucault, 2005). In this article I will focus on different positions of knowledge to discuss the meaning of integration in public policy.

The texts that I draw upon are selected official documents that in various ways express explicit interpretations of what integration is interpreted to be as a policy problem, (diagnosis) which interventions are suggested to meet that problem (prognosis) and how are such interventions motivated and legitimized (motivation). The types of documents relevant for the analysis are:

– Laws concerning provision of welfare and distribution of welfare

– Norwegian Official reports concerning immigration, and welfare (often used to as the basis for new legislation or new policies)

– Norwegian Reports to the Storting concerning immigration and welfare

Before I draw the timeline, I will present a set of relevant concepts, which will constitute the theoretical basis for the analysis.

Relevant theoretical concepts

When discussing integration, some researchers stress the absence of social exclusion (Dahrendorf, 1995; Woolley, 1998). Other researchers focus on the importance of various forms of social capital (Bourdieu, 2011; Coleman, 1988) (Robert D. Putnam, 2001). As we shall in the analysis, social inclusion has in many instances replaced the original concept of integration. Also the awareness of exclusion mechanisms has contributed to a larger awareness of social justice.

However, the traditional method of understanding integration emphasises norms and values. In social science the term integration was introduced by Emile Durkheim and is often associated with the question of how social order and cohesion can be maintained in societies undergoing profound changes and dissolution of norms and values. Durkheim was concerned that during his time society’s various institutions – the church, the family, traditions were dissolving and were unable to socialise individuals into existing norms and values. Durkheim assumed society would devolve into chaos and destruction in the absence of the strong norms carried by these institutions.

People in the 20th century might share the same concern and pose questions about how one can preserve the values of the nation, the welfare state, and religion, and still maintain a stable society in times of globalisation and extensive immigration. Discussions on these questions often employ the concept of social cohesion. Jenson (1998) suggest a five dimensional model:

i) Belonging/isolation,

ii) Inclusion/exclusion,

iii) Participation/non-involvement,

iv) Recognition-rejection, and

v) Legitimacy – illegitimacy.

(Jenson, 1998)

Network and O’Connor (Canadian Policy Research Networks & O’Connor, 1998) brings up three similar dimensions:

i) Ties that bind (values, identity, culture),

ii) Differences and divisions (inequalities and inequities, culture, geography),

iii) Social glue (associations, network, infrastructure and identity)

Several researchers stress the significance of common values in relation to social cohesion. In the Diversity Report (St. meld. 49 (2003-2004)) the question of core values is raised:

The question of core values is also a question of which ambitions we should have based on the level of community between citizens and various groups in society. One stance is to search for broad consensus, that in terms of cultures and values we try to approach each other. Another stance is to define a minimum set of human rights and political rules of conduct that must be respected by all. The maximum solution – the broad unity of values – aims to strengthen among citizens the feeling of belonging to the same collective unit. The minimum solution, to a greater extent, protects the right to be different even if human rights and politics limit the exercise of this difference. This report is closest to the latter understanding. (Author’s translation; St. meld. 49 (2003-2004): 34)

Here the question of cohesion is associated with society’s core values. The quotation clearly states that the aim of policy is moving away from broad, all-encompassing value consensus in society towards more value differentiation, where a few core values are established to protect individuals and maintain social cohesion. Such a move could be interpreted as a modern form of transition from mechanic to organic solidarity. In the classical meaning of integration presented by Durkheim, core values are associated with the collective consciousness of society as a whole. A strong collective consciousness would depend on a broad consensus of values. Social cohesion based on a broad value consensus focuses on society as a whole and reflects the classical meaning of the term. A society based on traditional or religious values shared by the majority of the population would be an example of this. This represents the maximum solution. The minimum solution on the other hand, aims at protecting the right to be different from the core values, where you can chose your religion and your cultural practices, chose your sexual orientation, live your life in different ways than the majority, and still have the respect from society. The sum of these individual choices might represent a challenge for social cohesion. In terms of Jenson’s five binary concepts mentioned above, one can ask do the increased diversity lead to belonging, inclusion, participation, recognition and legitimacy, or does it rather bring isolation, exclusion, non-involvement, rejection or illegitimacy? And in what way can society hold the different individuals together like “social glue”?(Canadian Policy Research Networks & O’Connor, 1998) These questions cannot be fully explored here, but will serve as underlying reflections as we move into the construction of frames.

When we talk of integration in the more modern sense of the word as it is used in politics, t refers to the participation of immigrants in their new societies (Rugkåsa, 2012). By this interpretation, integration not only refers to society as a whole but also concerns individuals in terms of skills, attitudes, and individual resources. It concerns the material basis for individuals to participate in society and how the structural underpinnings of the system either facilitate or impede the possibility of participation. Understood this way, integration also pertains to the ability of a system to combine a multitude of beliefs, identities, and practices, and questions the tendency to include or to exclude.

In the case of Norway, these questions must be discussed in relation to the Norwegian model of welfare. Lately there have been political discussions on how increased immigration has influenced the welfare model. The Official Norwegian Report on welfare and migration addresses this issue, where the Norwegian welfare state is described as a comprehensive welfare model and a “social integration project” with three key ingredients: democracy, citizenship, and modernisation (NOU 2011: 7). The welfare model represents both the problem and the solution when it comes to integrating immigrants. While there is an implicit assumption that fulfilling people’s social rights leads to social integration, lately the opposite has been argued – that rights to social benefits also can be seen as an impediment to integration or to including immigrants in the labour market. In many ways the lives of immigrants have been improved because of assistance from the welfare state. At the same time, long-term passivity and clientification is not beneficial for the individual or for society (ibid). These problems represent more than just a challenge to the welfare system, but an overall challenge to social democracy in general in terms of the lack of participation and the need for general trust in the population.

If the Norwegian Welfare State in itself is to be considered a social integration project, new issues are raised when new, larger groups of people who have not gone through basic socialisation in Norway immigrate and settle here. The degree to which they are considered epresentatives of cultural differentness, have special needs, or are subjected to social marginalisation also contributes to challenging the function of the welfare state and the basis for the legitimacy of the common good. (NOU 2011:7; English Summary: 4)

This quotation illuminates different representations of the problem of integration, and shows how this understanding, implies conceptions of challenge for the welfare state. It questions the efficacy of the socialisation process and emphasises immigrants’ unfamiliarity with Norwegian norms and values, their cultural differences, special needs, eventual marginalisation – all of which in turn frame tasks for the welfare state. As this article will show, integration issues in Norway over the years have been framed as welfare policies. These policies very often concern distribution of benefits and resources, and there has been an underlying assumption that welfare contributes to integration and to social cohesion.

Framing integration – redistribution, recognition and activation

If integration is framed in terms of welfare, it means the aims and concepts of welfare are used also to study integration. Verloo and Lombardo’s dimensions of “location” and “mechanisms” in frame analysis as mentioned above, could suggest the location of the integration policy into the location of welfare institutions, controlled by the welfare instruments and the values of the welfare society (Verloo & Lombardo, 2007). In the construction of frames we shall see that the legislation on social benefits played a very important role, as well as Social service offices, and also formal and informal criteria for citizenship. When discussing welfare we know that welfare has a universal orientation, which embraces all citizens. This means that all citizens – the elderly, the unemployed, the disabled, the poor, and the immigrants – they are all in a sense entitled to be a part of society, they have the right to integration. As such, the question of integration is also a question of social justice. Three central concepts concerning social justice are redistribution, recognition, and activation.

Fraser (2009) focuses on the first two concepts and states that claims for social justice often are connected to the way society redistributes resources or the way society values or devalues individuals or groups. Redistribution has often been defined in terms of class, social democracy, or social-economic reforms and defines injustice as primarily socioeconomic. Recognition, on the other hand, has to do with social and cultural representations and the way these are interpreted and communicated in society. The following table is based on Fraser’s argument:

Two paradigms of social justice

|

|

Interpretations of injustice

|

Examples

|

Remedies

|

|

Redistribution

|

Socio-economic distribution of ressources

|

Exploitation, economic marginalization, deprivation

|

Redistribution of income, reorganizing division of labour, transforming economic structures

|

|

Recognition

|

Social and cultural representations

|

Cultural domination, non-recognition and disrespect

|

Cultural or symbolic change towards positive evaluations of diversity and validation of individual identities

|

(Fraser, 2009: 24)

Fraser first claims that the redistribution paradigm is broader than class; other principles for distribution, such as socialism and social democracy, are also included. The recognition paradigm involves more than the widely known identity politics based on gender, sexuality, and race. On the one hand, it advocates rights that are specific to gender, race, or sexual orientation in a way that underlines and valuates these aspects of identity. On the other hand, recognition also involves a deconstruction of identities that rejects an essential conception of these, suggesting instead that identities can be constructed in multiple ways.

Fraser argues that the emancipatory aspects of the redistribution and recognition paradigms must be combined in a common comprehensive framework, in a way in which both paradigms are treated as dimensions of justice that cut across all social movements. Thus, injustice can be traced both to the politics of distribution and to culture for oppressed groups. These groups suffer from both misdistribution and misrecognition, although “neither of these injustices is an indirect effect of the other”. Rather, they are both “primary and co-original” (Fraser, 2009: 75). Fraser suggests examining institutionalised patterns of social interaction that focus on social status rather than specific group identities to determine whether reciprocal recognition and status equality exist. Do institutional patterns constitute actors as peers who are equally capable of participating in society? To what extent do institutional structures facilitate or impede parity of participation? As we shall see in the first part of the analysis, the Norwegian Social Care Act of 1964 could be seen as an example of an institutional structure that contributed to clientification and stigmatisation, thus preventing parity of participation. We can assume that the social benefits given under this law were seen as a redistribution of society’s resources that eventually would help integrate individuals into their new society. Based on this assumption, one could also argue that people receiving these benefits suffer from misrecognition in society because they were regarded as clients, as unproductive, and as a burden to society.

Fraser emphasises the structural and institutional basis for misrecognition and suggests that misrecognition is a deeply rooted problem in itself, and should not be analysed with redistribution. Other theorists disagree with Fraser and interpret recognition on the level of interaction: recognition from others through interaction is a condition for self-esteem and undistorted subjectivity (Taylor, 1994; Honneth, 1995). In this way recognition is seen as related to self-realisation and ‘good’ ethical conduct, more so than as part of an institutional structure. If recognition is connected to self-realisation and self-esteem, Fraser questions how recognition can also be seen as a matter of social justice. She calls this a sectarian approach rooted in individual psychology, whereas she herself would emphasise that social justice is rooted in social relations and institutional patterns. When the concept of recognition is related to integration in this paper, it has to do with absence of discrimination, but also to do with affiliation and belongingness. The way society takes measures to fight discrimination and strengthen affiliation and belongingness, could be seen as ways to change the institutional patterns that facilitates recognition and participatory parity.

In this paper, recognition, when connected to integration, is treated as related to the absence of discrimination and the presence of affiliation and belongingness. The measures taken by society when fighting discrimination and strengthening affiliation and belongingness could be seen as ways of changing the institutional patterns that facilitate recognition and participatory parity.

In addition to redistribution and recognition as central concepts concerning social justice and welfare, researchers also point to the paradigm of activation.

Activation is a key notion in the European employment strategy, and activation policies and programs are main instruments to promote the transition from welfare to work and to (re)integrate people dependent on social insurance benefits or social assistance into the labour market. This has happened simultaneously with increased migration and a resulting ethnically diverse workforce. (Djuve, 2011: 114)

Giddens (2001) asserts that in Europe social protection of citizens previously was provided in the form of transfers, but now transfers are more conditional on participation in training and job preparation (Giddens, 2001). This is seen as an investment in society that will eventually pay off. Activation could be seen either as a general introduction to the labour market, regardless of the type of job, or as preparation for a specific job that requires relevant skills (Dean, 2003). Djuve (2011) points out that the activation trend is particularly important for studies of integration policy, because of the close links between integration policy and citizenship as a fundamental right. She also states that activation seems to be applied more eagerly to foreigners. Activation is also mentioned explicitly in NOU, 2011:

This alternative represents a shift from pure income transfers to more systematic efforts to activate relevant groups in the form of qualification and adapted work, in combination with work-related wage subsidies and a more comprehensive use of graded benefits connected to health-related benefit needs. (NOU, 2011: 7; English summary: 13)

The paradigm on activation is characterised by three orientations of societal intervention: an individual approach, an emphasis on employment, and a contractualisation approach (Revilla & Pascual, 2007). The individual approach has to do with “tailoring” the individual to fit the demands of the labour market, and the tendency to promote the individual’s involvement in his own integration. This represents an ontological change, emphasising individual responsibility, citizenship, and agency. The second approach aims at strengthening labour market attachments and enhancing economic autonomy. Revilla and Pascual (2007) argue that employment is now to be seen more as a civil duty than as a right. The task of the welfare state has addressed protect against the risks inherent in a market economy, but now there is a tendency to encourage individuals to adapt and be flexible in relation to the ever-changing economy. The third approach emphasises contracts and focuses more on the economic aspects of citizenship than the social ones.

In addition to the contract as a key to social regulation mechanism, the ‘reciprocity’ norm is reaffirmed, and ‘deservingness’ becomes one of the key principles underpinning the legitimacy of citizenship itself. (Revilla & Pascual, 2007: 5)

Djuve (2011) is also pointing to the changes in citizenship under the paradigm of activation. She asks if activation is eroding social citizenship by revoking rights.

She found that the activation discourses in Norway has clearly been influenced by ideas of empowerment and political/gender equality, and in this sense Norway as a social democratic welfare state, constitutes a distinctive case. Social democratic ideas remain central, and the elements of activation are included in ways perceived by different actors as solutions to earlier problems (Djuve, 2011).

In a broad sense, the theoretical development shown here, demonstrates a turn from seeing integration as a question on social cohesion, to seeing integration more as a question of social justice, or also a question of social economics related to welfare. Equipped with these paradigms I will now present the timeline of the analysis and the following construction of frames.

Frame analysis of ethnic minority integration in Norway – drawing the timeline

It is difficult to analyse social policy related to integration because this is not a delineated policy area. Integration before the 80s, it seems, had been connected to an overall immigration policy, only later being connected to various policy areas, including citizen participation. In the 90s integration could also be defined in terms of cultural policies and later also in terms of policies of diversity. At present, integration and inclusion politics are diffused into almost every policy area. In the material presented, we will see that integration as a contested concept has been changed and redefined many times. It is this process of redefinition that I will try to contextualise and discuss in the following section. As the concept appears in public policy, it is framed around specific understandings of the underlying problems that the policy should address. By using policy documents, I will establish six frames of seeing “what is the problem represented to be” in a specific period of time. Within the context of each frame, I will develop the concepts of diagnostic framing, prognostic framing, and motivational framing.

The time period of analysis spans from 1975 to 2012. It is not possible to give an exhaustive account of events and developments within the field of immigration and integration during this period, but I will highlight some essentials, supported by contributions from existing research. As Tjelmeland & Brochmann (2003: 208) note; by exploring history, we recognise that “immigration sets the lens on the recipient country itself, history and traditions, political values, self-reflection, and identity” (author’s translation).

The year 1975 was chosen because in this year an immigration freeze was officially declared in Norway. Before this time, there were few immigration regulations. Like the rest of Europe, labour immigrants came from countries like Turkey, Morocco, Greece, and Pakistan. Concentrations of these groups were found in big cities, mainly in Oslo. After 1975, the groups that had been exempted by the immigration freeze were individuals applying for political asylum (refugees), students, those seeking family reunifications, and people with special skills needed in the labour market (Ihle, 2008; Tjelmeland & Brochmann, 2003).

For Norway since 1960, we can identify three waves of immigrants: labourers from southern Europe and Pakistan who arrived from 1960–1975, families of these labourers who came later in 1970–1980, and refugees and asylum seekers from many countries who arrived from 1975 to today (Tjelmeland & Brochmann, 2003). After the extension of the EU in 1994, a fourth wave can be identified: labourers from new EU-member countries in Eastern Europe.

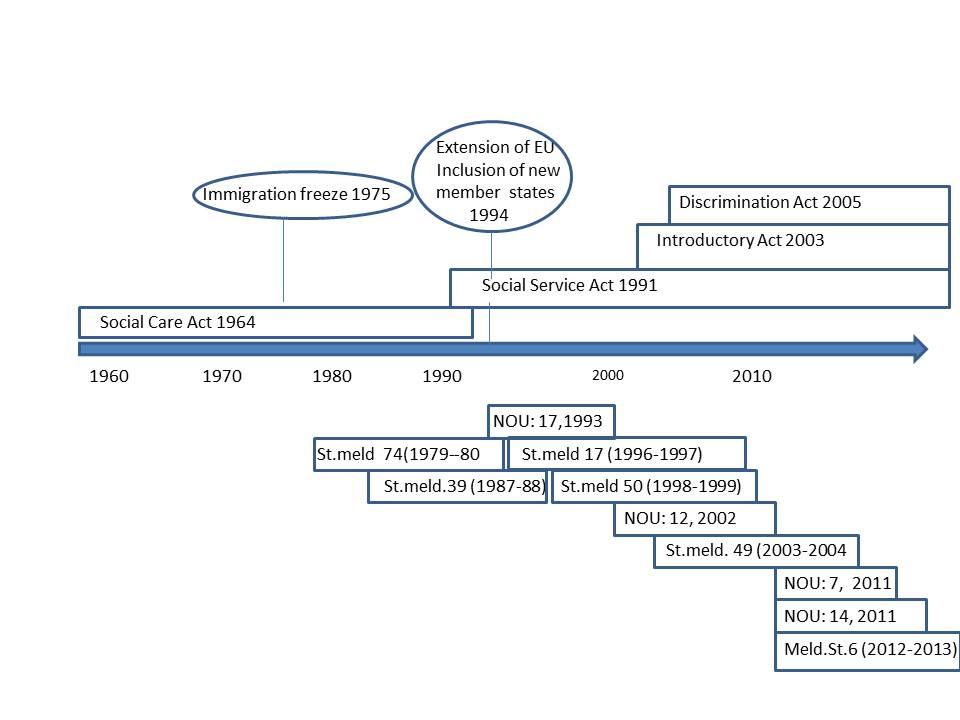

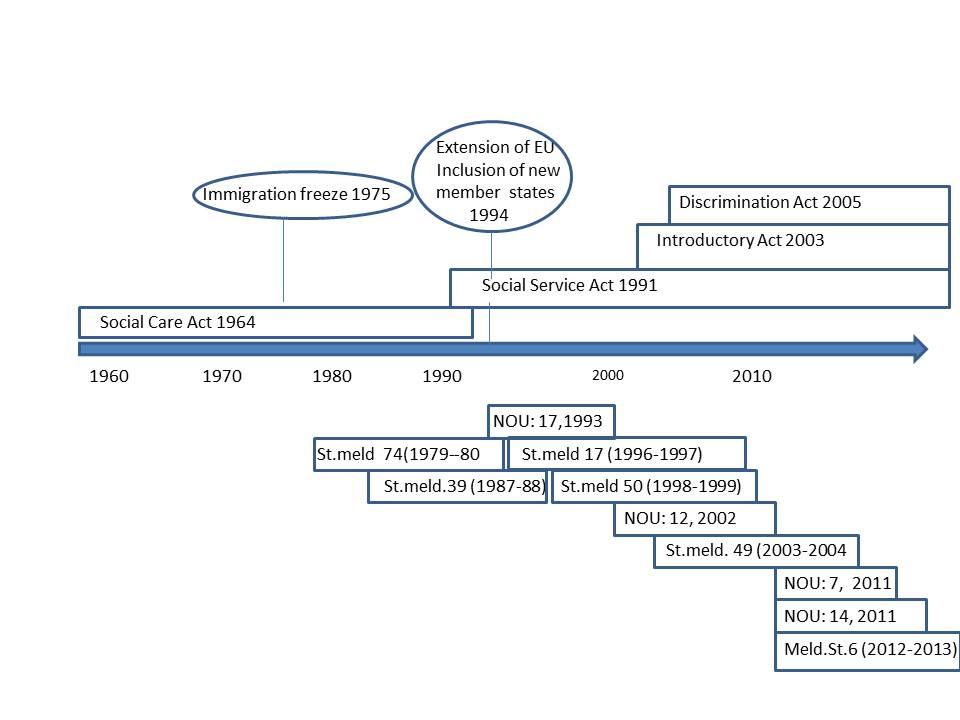

Timeline showing legislation, events, and publication of documents

(click to enlarge)

(Timeline with relevant laws, events, and selected documents; St.meld./Meld. St.: Reports to the Storting; NOU: Norwegian Official Reports)

The timeline above indicates the laws that I will refer to and the documents selected for the present analysis. I have also referenced the immigration freeze in 1975 and the extension of the EU to new member states in 1994. After the immigration freeze, a substantial portion of immigrants into Norway consisted of refugees and their families, who were given a residence permit for humanitarian reasons. These immigrants include those who have gone through the asylum application process, those who have been selected for Norway via the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and the flow of family members who have been connected to these people.

Refugee politics during the 80s was included in the general immigration policy and was institutionalised in a new management structure.

Immigration policy is employed as an overall concept, despite the reasons for immigration and independent of the grounds for residence permits. (Author’s translation; St. meld. 74 (1979-80): 6)

At this point, immigration politics and integration were seen as quite identical and were associated with the same policy area. As we shall see, immigration control and integration were separated at a later stage.

In the following, I will describe some characteristics of the aforementioned time periods. Those characteristics are related to legislation and specific documents relevant for that period. The presented descriptions will be fundamental when analysing the constructed frames of understanding.

1975-1991: Individuals in need – care and clientification

The basis for working with refugees and unemployed immigrants during the 1970’s and 1980’s was the Social Care Act of 1964. In many municipalities the Office for Social Services was responsible for refugees, and since refugees mostly came “empty-handed” from countries ravaged by war and conflict, they were looked upon as “in need”. The Social Care Act was to a large extent based on a “philosophy of treatment” – a conception of emergency as an individual and temporary problem that, through economic support and counselling, could be resolved within a short time period.[1] This was an expression of “treatment optimism” and “a fundamental belief that the welfare society could identify and solve social problems.” (Bernt, 2003) Being defined as “in need” could refer to the need for economic support, language training, housing, education, work, health services – basically everything. Language acquisition was seen as the main asset in a person’s integration process, which is why interpretation services and language training centres were established and developed. Having a different language could be seen as an obstacle that had to be overcome, as well as different culture and traumatic experiences.

The Report to the Storting 39 (1987–88) mandates including integration policy in municipal responsibilities through local social services as a part of a general welfare programme. Despite local variations, this meant providing social benefits without explicit claims of participation in specific qualification programmes (Djuve, 2011).

In order to fulfil the requirements for social benefits, people would have to be assessed individually as clients and would be left to the discretion of the social worker. This assessment easily could be associated with the search for deficiencies, and the deficiency concept itself might have constituted an important diagnostic framing. The problem of integration in this sense would lie in pinpointing immigrants as “lacking something” or as “needing something” – language skills, cultural competence, housing, management of post-traumatic stress, among others. Many researchers in Norway have stated that immigrants are often categorised as different from the majority in the sense that difference is interpreted as a deficiency (Djuve, 2011; Gullestad, 2002; Vike, Liden & Lien, 2001; Vike, 2006; Ytrehus, 2001).

There are reasons for believing that the law, with its implicit care orientation, contributed to the interpretation of difference as deficiency. The approach here focuses on the skills and assets of individuals, defining who is “thoroughly integrated” and who is “poorly integrated”, as though on a scale (Ihle, 2008). This can be interpreted as a claim for functionality, where society has to provide for the ‘deficient’ individual. From a functionalist point of view, this could also be seen as a societal compensation strategy for making individuals behave in more functional ways. In a Dürkheimian sense, individuals who don’t have the necessary resources and do not know the norms, values, and language of society, could be considered deficient and seen as a threat to society. In this functionalist terminology the system maintains social order by controlling for and compensating individual limitations (Tjelmeland & Brochmann, 2003).

The Report to the Storting 39 (1977–88) states accordingly that it is the duty of society to minimise differences and level the conditions that influence people’s lives:

The point of departure is that human beings have different needs conditioned by social, environmental, and economic factors. It is the duty of society to try to reduce these differences in conditions, or reduce the effects of these through compensatory programmes for those who are worse off than others. This point of view implies special targeted measures – “særtiltak” – that delineate social differences in individual conditions and living conditions. These measures are implemented by many different groups in society in many different areas of life. (Author’s translation; 47)

Therefore, where the diagnostic framing had to do with the focus on individual limitations or individual needs, the prognostic framing had to do with compensatory programmes for developing individual skills and creating equality. Provided with the necessary skills, the individual could be on the same level of preconditions, and on this basis have the same opportunities as Norwegians (Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008).

Providing immigrants with the above-mentioned skills and opportunities appeared to be an enormous undertaking for the system, and during the 70s and 80s this effort was severely criticised (Djuve, 2011). First, it challenged the fundamental concept of legitimacy and the “social contract”, which often refers to the protection of society against the risks of the market economy, although it also can be seen as a reciprocal exchange of rights and responsibilities. Extraordinary compensation programmes for immigrants could appear as conflicting with the principle of universalism in the welfare state because of the lack of reciprocity (Djuve. 2011 Rugkåsa, 2012). Second, compensating people’s differences in terms of welfare – by helping them catch up to the level of others and gain access to essential resources – seemed a difficult aim to operationalise and implement. Third, this compensation effort could be interpreted as an assimilation strategy, wherein the effort towards equality also means encouraging immigrants to adopt the majority culture (Djuve, 2011). These arguments in turn influenced the motivational framing under the core concept known as “likestilling”, literally equality in terms of position, although this might also be described as “mainstreaming”. Brochmann and Kjelstadli refer to this as real equality as opposed to equality politics(Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008). They do not explore this difference, but they do indicate that equality politics has to do with the inclusion of immigrants in the social welfare system. Real equality, by contrast, would have to do with equal access to resources and to social venues in society like for instance schools, workplaces, political parties or the like.

The Report to the Storting “On Immigration Policy” (Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88) highlights this idea, and declares explicitly the aim of creating “equal positions” or mainstreaming.

This policy will aim to maximise mainstreaming between immigrants and Norwegians. This implies that immigrants, as much as possible, should have the same opportunities, rights, and duties as the rest of the population. It is worth noting that the aim of mainstreaming between different groups is not specific to the politics for immigrants. It is in line with the ideal of solidarity in the welfare state, based on the principle of equality and equal worth between society members. It is also in line with the conception of a just distribution of societal resources and societal duties, with the overall aim of extensive welfare for all. (Author’s translation; Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88: 47)

This report is also very clear that the concept of mainstreaming implies that immigrants should have the same actual opportunities as the rest of the population. They should have access to all public services and have control over their own lives through active participation. The implication here is that all immigrants are offered the opportunity to learn Norwegian, to gain knowledge that will help them orient themselves in society, and to receive an education. The report also emphasises economic and social security as a necessary condition for immigrants to live as equals with the rest of the population, so that they also can maintain their own cultural identity and live in harmony with their environment (Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88:48).

The motivational framing of the Report to the Storting 39 (1987–88) largely had to do with defending the necessity of compensatory programmes or targeted measures in order to achieve mainstreaming. It says explicitly that “these measures should not be perceived as specific advantages for immigrants” (ibid):

The aim of targeted measures is to remove or reduce hindrances or difficulties that immigrants meet in their new environment, so they can achieve a real, equal position compared to the rest of the population (Authors translation; Stortingsmelding 39, (1987-88): 48).

Targeted measures were severely criticised, basically because they were seen to be favouring immigrants before over groups of the disadvantaged among the native Norwegians.

A motivational framing – arguments to defend this policy and the extended benefits to individuals – focused on the temporary nature of this support and also emphasized the aim of equality that supposedly would be reached when the benefits and programmes enabled people to stand on their own feet. Nevertheless, if welfare benefits flowed disproportionately to immigrants, the legitimacy of the welfare system itself might be weakened (Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008; Djuve, 2011). Indeed, these targeted measures were severely criticised for favouring immigrants over the disadvantaged among native Norwegians. Moreover, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, an increasing number of immigrants were receiving social benefits over longer periods of time. The allegedly temporary welfare initiatives – through targeted measures – turned out to be not so temporary after all.

1987 – 2000: Integration as the preservation of culture – A tribute to “colourful community”

When asking “what’s the problem represented to be” in terms of integration and culture, it is difficult to find a kind of diagnostic framing explicitly stated in the early political documents. What is very apparent, though, is a tribute to cultural difference as an ideal for a modern, pluralistic, democratic society (Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88). When looking at the 1980s and 1990, researchers point to an extensive and prominent discussion on assimilation and integration (Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008; Djuve & Hagen, 1995; Eriksen & Sajjad, 2006; Gullestad, 2002). While these researchers describe assimilation in various ways, the common thread treats assimilation as absorption into majority society when cultural specificities are muted and when immigrants conform with the majority in the strongest possible way. By contrast, an integrationalist point of view would mean that immigrants could preserve and practice their own culture while still participating in the different venues of mainstream society. It seemed quite obvious that an assimilationist approach was incompatible with the inherent political egalitarian values in Norway. Integration based on the preservation of culture, on the other hand, was the obvious political goal, especially for the more leftist side of government. Furthermore, Norway was heavily influenced by the rest of Europe, which was experiencing the spread of multiculturalism and the belief in “cultures in a plural sense” existing side by side in the context of modern nation states. Assimilation would oppose true pluralism, and should therefore be avoided and fought against.

From this point of view, assimilation was a potential problem, and much of the diagnostic framing centred around this. For starters, Norway was, through the UN Convention on Social and Political Rights, committed to respecting and allowing immigrant cultures:

Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to respect and to ensure to all individuals within its territory and subject to its jurisdiction the rights recognized in the present Covenant, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. (United Nations Declaration of Social and Political Rights, 1966: Article 2.1)

Second, Norway had a history with traditional ethnic minorities, where national authorities had practiced severe assimilationist strategies in the Norwegian nation-building process, especially with the Sami population in the north (St. meld. 49 (2003-2004)). This policy had been strongly criticised both nationally and internationally.

Both immigrants and minorities connected to Norway were in the same period met with claims of “Norwegianising” and unilateral adaptation to society. Many people at the time saw “Norwegianising” as a condition for these groups to adapt to society as equal citizens. The language and culture of minority groups had low value, and there was an attempt to erase them. (author’s translation; St. meld. 17 (1996-1997): 24)

For assimilationists, culture was often seen as an obstacle that has to be overcome in order to achieve equality and integration. The idea of culture as an obstacle fit neatly with the problem orientation in the application of the Social Care Act, as mentioned above.

Third, culture was seen as part of larger series of social problems – unemployed, low income, poor housing, low degree of interaction, low education, and foreign culture combined as comprehensive attribution of particular people. In this way culture could become one of many factors that had to be dealt with by the social system in order to “improve” a person’s situation (Ihle, 2008). At the same time, however, this can be viewed as a way of helping to develop the person’s individual skills – including the processing of so-called cultural artefacts – in order to become more functional. It could also be seen as a quest for conformity from the system, which also expresses a value orientation when defining the majority culture as more valuable and important than other cultures. Where the majority perceives immigrants as different, the concept of difference, as mentioned above, could be interpreted as deficiency, and thus not validated by society. Rugkåsa (2012) states that whereas the missing integration among native drug abusers, elderly people, persons with disabilities are ascribed to individual factors, the missing integration among immigrants, are ascribed to culture.

Having a different cultural belonging than the majority, could then easily become identical with a lack of the right cultural competence (Gullestad, 2002; Rugkåsa, 2012). A consequence could be that the immigrants would not be included in the community before they have acquired the cultural skills that are considered necessary by the majority population (Rugkåsa, 2012). In this way the system could be practising assimilation, whereas integration was the ideal presented in the political documents.

In trying to determine the diagnostic framing of culture and integration, there is an ambiguity in policy that is deeply rooted in this discussion on assimilation and integration. On the one hand, one’s own immigrant culture is seen as an obstacle that has to be processed or altered in order to achieve integration. On the other hand, practising and preserving one’s own culture is seen as a prerequisite in order to achieve integration. This second point is very prominent in the policy documents and also the core of prognostic framing.

In the opinion of the government, an anchoring in one’s own culture and environment will ease the possibilities for immigrants to adapt and function in the majority society (to integrate) (…) To maintain and develop one’s own language and culture, should not be seen only as means in an integration process. To the immigrant, to be able to maintain your identity and attachment to your original environment has a value in itself. (…)The core of the politics towards immigrants is that they should be able to participate in the life of society – politically, economically, and socially – without the claims of cultural assimilation. It should be fully possible for immigrants to be able to live here as accepted members of society, at the same time as they build on their cultural legacy. (Author’s translation; Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88: 47-49)

To support these aims, there was wide public support for immigrant communities and cultural activities. There was also an effort to adapt public sectors to immigrants as new users of services. This could have to do with language and the need for interpretation, but it could also have to do with adjustments according to ethnicity and religion. The need for efficient language training was also prominent, as language is very tightly connected to culture. So, by learning Norwegian, one would also assume that this implied learning about Norwegian culture. As we will come to see later, learning about, or acceptance of, new cultural values is a lengthy process.

The motivation and reasoning behind this policy could be seen in some of the policy documents. We can identify three factors in the motivational framing, namely the principle of eligibility or individual choice, respect, and cultural enrichment to society. The Report to the Storting 39 (1987–1988) on “Migration Policy” emphasises quite explicitly the norm of individual choice when it comes to culture. This was elaborated already in Report to the Storting 74:

The principle is that an immigrant should be able to choose how strong and how long term the stay and attachment to Norway should be. One does not want to claim that the immigrant should be as Norwegian/assimilated as possible (Author’s translation; St. meld. 74 (1979-80): 28).

The Report to the Storting 39 follows this up by establishing the principle of respect:

It is the view of the Ministry that a more appropriate concept for the intention that lies in the principle of eligibility is respect for immigrants’ language and culture. The principle of respect for immigrants’ language and culture will be kept to emphasise that immigrants should not be forced to become as Norwegian as possible in the shortest possible time, unless that is what they wish themselves. (Author’s translation; Stortingsmelding 39, 1987-88: 49)

This report goes on to argue how the public sectors can facilitate and support immigrants in preserving and maintaining their culture. Cooperation, mutuality, and tolerance are leading concepts in the policy towards immigrants. This means that immigrants should be able to participate in Norwegian political life and that they should maintain their own cultural activities. Report to the Storting 39 (987–88) echoes this sentiment when stating that “the positive sides of the cultural influence from immigration should be our focus of attention” (49).

The concept of cultural enrichment of society served as political legitimation for the implementation of many measures under the banner “fargerikt fellesskap”, or “Colourful community”. The 1990s could be defined as the era of multiculturalism, where the cultural influence of immigrants was supported, and there was an attempt to integrate this influence into the nation’s existing cultural life. Culture was in this context defined in terms of its expressions and artefacts – like music, dance, and literature. Culture in another sense had to do with access and participation as a dimension of welfare and recreation. Culture also had to with human and civil rights.

Related to this, social scientists have engaged in a long-term discourse on the meaning of culture and the need for a reconceptualisation of culture to adapt to the new, shifting environments of multiculturalism (Gullestad, 2002). First, this had to do with a critique of the established understanding of culture as static, value neutral, descriptive, and based on essential, accepted characteristics. Second, in the descriptions of a given culture, nation states were often referred to as the unit of analysis, where critics would point out that the nation state, as a coherent force, had withered (ibid). The nation state could be seen as a social construct, serving particular purposes, and the sense of community it offered could be seen as a kind of “imagined sameness” (Anderson & Andersen, 1996). If culture was seen as constructed, imposed on the individual from the outside, it could also be seen as enforced, hegemonic structures of society (Gramsci, Hoare & Nowell-Smith, 2001).

In the traditional concept of culture – often referred to as cultural essentialism – non-Western cultures are often perceived as traditional and static. By being associated with those cultures, immigrants would be perceived as carriers or representatives of those cultures, rather than being innovators or agents in their own right (Ihle, 2008; Ytrehus, 2001). By perceiving immigrants as determined by culture and tradition, as marginalised and deficient (as described earlier), and as different in terms of norms and values, the obvious response could be assimilation, even if integration was the strategy of the political agenda.

1990 and forward: Upheaval of living conditions in specific social groups

During the 1990s, growing social inequality in Norway began to be identified. This inequality was largely in contradiction with the established belief in Norway as an egalitarian society (“likhetssamfunn”) – a society of equals. In a way, the conception of “likhet” (similarity, equality, or sameness) has constituted a fundamental ontology of the Norwegian welfare state. The state should be responsible for equal opportunities for all citizens regardless of gender, geographical location, or family income level. To achieve this aim, the state would need an epistemology – a more fundamental knowledge of social differences – and also a methodology of how to measure, assess, and analyse these differences. This is where the concept of living conditions (“levekår”) comes in.

In the 1990s the number of clients depending on long-term social benefits was increasing. Clients were generally unemployed people, including early immigrants who had worked as unskilled labourers since the 60s and 70s. At the same time, there was also an increase in the number of young drug abusers, single mothers, and young school dropouts. Refugees and their families were also dependent on social benefits as they arrived in Norway, and as such they became part of the growing queues of people at the social service offices. Unemployment rates were high during the 90s, and there was pressure on the social system and strong competition for jobs. In 1991 a new law was established: the Social Service Act, which replaced the Social Care Act of 1964. The new act aimed to reduce the effects of clientification, stigmatisation, and the orientation towards care. In the old law, treatment was based on the discretion of social workers, in the individual assessment of needs. The services and the benefits provided to people depended on this discretion, whereas the new law focused on more operational rights and claims of justice (Bernt, 2003). In spite of the new law, the same problems remained. Djuve and Kavli (2007) claim that the integration regime of the 1990’s was construed as a failure.

This statement pinpoints the burdens of being a long-term recipient of social benefits, as well as the extensive costs for society. According to Djuve, the criticism of the integration regime increased during the 90s, and a number of studies revealed the high rate of unemployment, high dependency on social assistance, poor living conditions, low levels of Norwegian knowledge, and extensive social exclusion in large immigrant groups (Djuve, 2011; Djuve & Hagen, 1995; Hagen, 1997; Sivertsen, 1995; Vassenden, 1997). This criticism pointed at questions concerning quality, continuity, and intensity in the services offered to newly arrived refugees. The criticism also pointed to large local variations in. Critics also claimed that the present system still contributed to clientification and that the system itself did not express and transmit Norwegian values to people new to the system (Djuve, 2011). In 1995 Norwegian anthropologist Unni Wikan cautioned against the rise of a new Norwegian underclass (Wikan, 1995). Brochmann and Kjelstadli also asked whether the state had done immigrants a disservice by (formally) encouraging “cultural preservation” that consigned them to the lower strata of the population (Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008).

In 1993 the Official Norwegian Report on “Living Conditions in Norway” and subtitled as “Is the grass green for everyone?” was published. The report’s highlights are as follows:

- Living conditions are determined by individual access to resources – like income, fortune, health, and knowledge – that people can utilise to govern their own lives. The focus on resources implies that living conditions are not something ‘given’ to people; they are also something that can be created and changed through conscious action, either individually or collectively.

- Living conditions imply a broad range of components, particularly health, employment, labour conditions, economic resources, educational possibilities, family and networks, place of residence and local environment, recreation and culture, security for life and property, and political resources and rights.

- Living conditions are measured by creating an overall picture based on large interview surveys geared at obtaining objective measurements. In addition, one can employ accessible economic and demographic statistics.

(Author’s translation; NOU 1993:17 & 42)

The importance and significance of equity of living conditions – as a system or ontology of social democracy, a system of knowledge and also a methodology – cannot be underestimated (Ihle, 2008). With the progressing technology in statistics, it was possible to conduct large surveys that could compare both geographical areas and groups of individuals across a large number of social indicators. With this approach, the understanding of integration became less about increasing individual skills and affiliation with culture, and more about access to resources on a collective level. This indicates that living conditions involve a mutual relationship between the individual and society, where the individual can access and employ resources – for instance, education and work opportunities – and society must provide these resources on an equal basis. According to this approach, this relationship is measured at the group level, showing positions in society related to social resources for various social groups. This is a different perspective than the previous focus on social care related to individuals.

Research and social policy on living conditions also included immigrants, and it is quite clear that the epistemology and methods of measuring living conditions also could be applied to analysing integration. We could go so far as to say that the measurement of integration and living conditions can be understood in practically the same way, when applied to the immigrant population. According to the research on living conditions, high score on these conditions, or these indicators would also imply a significant level of integration.

Surveys on living conditions that compare population groups are the most common way of measuring integration. The results do not present a complete picture, and must be supplemented by more qualitative data. But data on living standards are indicators of the situation. Measuring living conditions is crucial for maintaining welfare politics. Systematically low results for one group compared with other groups in the population are reasons for concern. (St. meld. 49 (2003-2004): 28)

With surveys on living conditions, the diagnostic framing in social policy was improved and more targeted. Immigrants became a dominant target group, and the surveys revealed indications of unemployment, low income, housing problems, health problems, and various other social troubles.

This perspective on living conditions represents an economic and statistical rationality that deals with measuring of welfare. By analysing living conditions, a scale of high and low standards for welfare was introduced, while average standards of normality were defined in the language of statistics. When defining a statistical standard of normality, one also presents those who deviate from these standards. In this sense, diversity in Scandinavia tends to appear as a relationship between normality and deviance, between the resourceful and the disadvantaged, between natives and those from other cultures (Vike, Liden & Lien, 2001). The use of categories in statistics and in social welfare, combined with strong media influence, contributes to societal production of knowledge and the understanding of defined categories as true and natural. On the other hand, this use of categories implies the commodification and cementation of extending, changing, and situational identities (Gullestad, 2002).

Through the analysis of living conditions, groups and people are scaled; a broad set of indicators yield an image of a group in a population to illustrate and document their position in society in terms of resources (Ihle, 2008). In this way, integration had more to do with the societal inclusion of immigrants as a target group for welfare in many areas of society. This led to a number of discourses and public debates. The most extensive had to do with equality and assimilation (Gullestad, 2002; Tjelmeland & Brochmann, 2003; Vike, Liden & Lien, 2001). Another had to do with categorisation and labelling of the term immigrant (Gullestad, 2002; Ihle, 2008; Rugkåsa, 2012). Another debate concerned a multicultural society and the position of being a majority vs many minority populations (Eriksen & Sajjad, 2006).

The shift in discourse here regards the previous understanding of integration as an aim for the individual. With the surveys on living conditions, the unit of analysis is no longer the individual, but ethnic minorities – very often portrayed as a single target group despite the internal differences. Over time, the understanding of immigrants as a target group for welfare has been severely criticised, and the diagnostic framing has been differentiated and has gradually begun referring to factors more specific than simply immigrant status, such as nationalities, continents of origin, gender, duration of stay, education, ethnic groups, and generational differences.

The prognostic framing following the emphasis on living conditions is a broad approach to welfare that involved many sectors of society – the labour market, education, health, housing, voluntary organisations, etc. This meant that what was previously a single immigration policy was now split into two areas: immigration and control, and internal integration. Internal integration, since the 1990s, was controlled by the UDI (the Directorate for Immigration), and responsibility for minority integration into society was placed on departments representing various sectors. This implied considerable differentiation of responsibilities, both on the state level and the municipal level. The amount of changes – bureaucratically, legislatively, and in policy implementation – was enormous during the 90s. We can single out three important change directions that are fundamental to the prognostic framing. The first was previously mentioned: the differentiation of policy across the field of welfare in all sectors and levels of society. The second came as a direct result of the living conditions surveys that revealed large concentrations of immigrants in the cities, especially Oslo. These concentrations appeared in combination with other indicators like poverty, poor housing facilities, low education, and health and social problems. Large programmes in specific geographical locations were established with state sponsorship. These programmes focused on renewing buildings, erasing poverty, bringing people into activity, and avoiding the development of social problems. Many people who lived in these areas, including non-immigrants, showed a low score on income, work, and education, and a high score on negative factors. Thus, these measures in the big cities could be referred to as integration schemes.

The third direction of change within the prognostic framing had a direct emphasis on qualifications for newcomers. In 1999 a national committee known as the Introduction Committee was appointed; its role was to examine and develop a proposal for a new law to mandate municipalities to offer an introduction programme for refugees who recently arrived to the country. The Introductory Act of 2003 emphasised the work line as part of Norwegian social politics in general, which entails both ongoing effort towards persons not easily absorbed by the labour market as well as working for a generally inclusive labour market (Ihle, 2008). This policy was introduced by the Brundtland Government in the Report to the Storting on rehabilitation (St. Meld. 39 (1991-1992)). Participation in this specific programme for refugees was made mandatory, and participation was connected to a standardised income, work and education preparation, and language training, combined with knowledge of Norwegian society. Participation in the programme should amount to 37.5 hours per week at a “normal” job, and existing rules for the labour market should be applied (NOU 2001: 10). The programme should have a standard timeline of two years.

These implementations were introduced basically to make the system of receiving immigrants more efficient and economically viable. The differentiation of politics and diffusion of responsibilities to various sectors was also important, signalling that immigrants were not “specific” clients of particular services, but part of the responsibility of normal institutions in society.

2000-2005: Absence of structural barriers, racism and discrimination

A legal development alongside the policy development of the new Introduction Act is connected to an official policy against racism and discrimination. Even though Norway is not an EU member, it does adapt various EU regulations and standards. The EU approach to social questions and human rights has undergone profound changes over time. Since the mid-1990s there has been a broad agreement on the need to effect measures against discrimination on grounds other than gender. The Amsterdam Treaty in 1997 established protection against discrimination along many dimensions, among them race and ethnicity. In Article 13, the Commission proposed two directives:

– The right to equal treatment independent of race or ethnic origin, and protection against discrimination in many areas (2000/43/EF),

– The need to prevent discrimination across a multiplicity of grounds (2000/78/EF).

When a National Action Plan against racism and discrimination was presented in 1998, it was a response both to the developments within the EU and also to reports of increasing discrimination taking place in Norway in the 90s.

By the end of the 1990s many investigations and reports questioned the extent to which discrimination and racism existed in Norway. Many reported a shortage of documentation of these issues and the need for better surveillance and reports (NOU 2001:10). The diagnostic framing is centred first and foremost around the labour market, public services, school and education, police/prosecution/courts, the Internet, and the local community. A report based on investigations in 29 municipalities in 2002, initiated by the Directorate of Immigration, states that there is a basis to claims that discrimination is a typical phenomenon in Norway, especially in the labour market, the housing market, at schools, and in public services.

Many municipalities report that exclusion is the most visible form of discrimination against immigrants. The term here covers the actions that, consciously or unconsciously, contribute to the fact that immigrants are not able to enter the labour market or that immigrants in work positions are isolated or pushed out of work. Exclusion can happen in the process of hiring, in labour adaption programmes, or at actual workplaces. (Author’s translation; Utlendingsdirektoratet, 1999-2000)

An important question for discussion was whether the high number of unemployed immigrants was caused by discrimination. In the Report to the Storting on Immigration and the Multicultural Norway it is stated that unemployment among non-Western immigrants was nearly three times higher than among ethnic Norwegians during the 90s (St. meld. 17 (1996-1997)). Berg shows how structural, cultural, and individual factors mean that immigrants end up last in the queue (Berg, 1996). The report concludes that efforts against discrimination and racism should have high priority (Berg, 1996). Djuve and Hagen (1995) were one of the first researchers who wrote about immigrants and living conditions. In 1995 they suggested four different explanations of what they call “the low integration level among immigrants” (basically referring to the labour market). The first had to do with the immigrant’s limited resources – income, language, network, education. The second pointed to discrimination. The third pointed to ‘cultural hesitation’- how culture in some instances would restrict people. The fourth emphasised institutional barriers.

All reports agree on a complexity of reasons behind the high rates of unemployment among immigrants, but they all also underline the existence of discrimination and exclusion. NOU 12 clearly states that “there is a reason to believe that discrimination is one of the reasons behind the high unemployment among groups of immigrants” (Authors translation)(NOU 2002:12). According to the statistics at SMED (Center Against Ethnic Discrimination), in 2003 there was an influx of registered legal cases related to the labour market, and also a large amount of cases related to health and social services, police, and immigration authorities (SMED 2003).

Three important responses constitute the prognostic framing of racism and discrimination. As racism and discrimination arose as an issue during the 1990s, many activists and voluntary organisations emerged. Examples of these are the Anti-Racist Centre, OMOD (Organisation against Public Discrimination), NOAS (Norwegian Association for Asylum Seekers), the MIRA Centre (Resource Centre for Minority Women), SEIF (Self-help for Immigrants and Refugees), and many more. Public initiatives came forward both as a result of the EU’s anti-discriminatory frameworks, as mentioned above, and pressures from the organisations and the media. The most important outcome in the process was first the establishment of SMED (the Center Against Ethnic Discrimination) in 1998 and later the preparations for new legislation against discrimination. The anti-discrimination efforts could be seen as an extension of the established gender equality politics that began in 1972 with the establishment of the Gender Equality Council and was followed by other institutions to secure gender equality. In the government session 2004-2005, the government suggested the establishment of a new ombud office to focus on issues of inequality and discrimination along the lines of gender and ethnicity. The Ombud of Equality and Discrimination came into office in 2005 to combat discrimination on a multiplicity of grounds: gender, ethnicity, disability, language, religion, sexual orientation, and age. This ombud was accompanied by a new act, Act Against Discrimination 2005. The purpose of this act was to protect against discrimination and incorporate various laws concerning discrimination, such as the Discrimination Act, the Gender Equality Act, the Work Environment Act, and the Housing Act. The motivational framing of this development relates to the government-proclaimed goal of offering equal opportunities to all members of society. Equal opportunity is incompatible with the existence of discrimination of any kind.

2003 and forward: Living conditions, identity, and belonging

Stortingsmelding 17 (1996–1997) on Power and Democracy describes an unfortunate development for the immigrant population in which a large portion of the population does not participate in the Norwegian system. The report expresses concern that parts of the immigrant population might become a new underclass consisting of people who work in low-income professions or are outside the labour market” (St. meld. 17 (1996-1997)). Moreover, many immigrants experience powerlessness in their encounters with Norwegian society. This might manifest as long waiting periods at asylum centres, dependency on social benefits, language problems, marginalisation in the labour market, and as we have seen various forms of ethnic discrimination (ibid).

The diagnostic framing of the 1970–1980s was related to individuals in need who were of a different cultural background than the majority population. The 1990s had more to do with measurements of living conditions, structural constraints, and the position of minorities as a social group. This approach emphasised that the concept of integration should be understood as a mutual relationship between individual and society. Individual skills and resources mattered, but society also would have to open up to facilitate immigrants’ access to different parts of society (St. meld. 17 (1996-1997)).

At that point there was an overall immigration policy that gradually became more complex, both by the Schengen Agreement and by the introduction of new member countries into the EU, but also by the consequences of war and natural disasters around the world that substantially increased the number of refugees into the country. This meant a strong focus on immigration control. At the beginning of the 2000s there was also a focus on providing new immigrants with a better introduction to society, resulting in the aforementioned Introductory Act of 2003. The process of differentiating the integration policy into various sectors was also underway, so that gradually one would find more references to aims for integration in education policy documents, in documents on urban housing and on health, and especially in policies concerning the labour market.

During the ongoing efforts to develop more sectorial responsibility for integration and create legitimacy for a more ‘colourful community, Norway was in the early 2000’s confronted with shocking news on cultural practices of forced marriages and female genital mutilation in other countries. This knowledge created distance between the majority population and parts of the minority population regarding how to react to certain cultural values and practices. Training programmes were severely criticised. The identification of cultural practices that violated basic human rights seriously challenged the previous glorification of multiculturalism and cultural relativism. It also led to many legal changes. This was not a situation of the majority versus minorities. On the one hand, it had to do with the right to practice one’s own culture and religion, and, on the other hand, it had to do with protecting individuals from practices rooted in culture and religion that violated basic human rights (Brochmann & Kjeldstadli, 2008).

“Diversity through inclusion and participation – responsibility and freedom” (St. meld. 49 (2003-2004)) is a Report to the Storting that attempts to redefine policy by drawing some lines and establishing a new epistemology. It presents the new policy as a politics for inclusion and diversity that aims beyond existing integration measures in the form of language training and qualification programmes.

Society must include everyone to reach the goal of a peaceful coexistence. An effective introduction and integration policy that shortens the time it takes for newcomers to stand on their own two feet without public support will provide great economic benefit for society. (Author’s translation; ibid: 25)

Integration politics here, on the one hand, has a more limited focus and is directed towards newcomers and first-generation immigrants. The politics of inclusion and diversity, on the other hand, is directed at all members of society and emphasises the following:

– the relationship between individual rights and regards for the community,

– the relationship between minority and majority,

– the conditions for harmonious coexistence.

The diagnostic framing of this paper is more complex and brings to the fore some important aspects of the immigrant experience:

– basic variables like gender, age, nationality/ethnicity, education,

– duration of stay in Norway,

– the fact that high participation in one area (like work) could mean low participation in other areas, and vice versa,

– the difference between first-generation immigrants and their descendants.

These considerations were shown by the living conditions surveys presented above.