The book tells, and documents, the author’s journey following his original intuition: can the geography described by Homer in his epics be related not to the Mediterranean coasts and towns, but to the Scandinavian ones? Vinci pursued such an ‘experiment’: he tried to fit Homer’s places into the Scandinavian context. And according to Vinci’s studies, partially supported by further studies by Nilsson and Tilak, the protagonists of the Iliad and the Odyssey could have actually lived and performed their heroic deeds on the coasts of the Baltic Sea. One of the starting and strongest points of Vinci’s research is already suggested in the ancient historical sources: Plutarch stated that Ogygia island, where Calypso kept Ulysses for several years, was in the Northern Atlantic, five days of navigation away from Britannia. Then, the evidences mingle with an unstoppable sequence of facts and hypotheses, reasonings and dreams. For example, why is it said that the island of Faro, in front of Egyptian Alexandria, took one day of navigation from Egypt?

As Vinci bears witness to with his studies, the names of Homeric places still overlap with the names of Northern villages and cities. The same applies to the distance between towns, the description of the warriors’ garments and habits, as further substantiated by well-documented archaeological and historical studies that match Vinci’s peculiar theory. Furthermore, there is an answer to the issue of the climate described in Homer’s poems: the Baltic Sea was warmer at that time, just before the end of the ‘climatic optimum’ that forced Nordic populations to move to warmer places, i.e. to the Mediterranean area.

As the cooling of the climate is concerned, I must confess that I felt myself shivering: what an intellectual vertigo does induce Vinci’s notion, whereby Europe’s classical culture shifts suddenly northward. Torn between my Mediterranean birth and my sympathy for Nordic countries, having visited Greece and the ‘epic’ places of Achilles and Telemachus, I still find it difficult to accept the idea that Ithaca may be one of the Danish islands, Troy to be in the Gulf of Finland, Crete in Pomerania, and Mycenae, perhaps, the ancestral cradle of today’s Copenhagen. Not to mention Ulysses–thus interpreting Tacitus’ definition–being a forerunner of the Vikings, maybe even the Ull recalled in the Edda.

Yet, as the classical scholar Rosa Calzecchi Onesti states in the foreword to Vinci’s book, none of the great previous researches on Homer’s geography is in doubt, because Vinci argues that such Northern populations recreated a second ‘Baltic’ along the Greek coasts and islands. As historical novelist Franco Cuomo writes in the preface, Vinci’s book must be “read like the memory of a population who, moving elsewhere, brings along its own myths” (p. 9) . Vinci’s book evokes Homer’s epics as a primordial portrait of a ‘greekness’ that we have learned to know and imagine through classical texts, visual arts, movies, travels, etc. We know that history is crowded of misunderstandings and misinterpretations, and Vinci’s theory shall be seriously considered as a new approach to Homeric and classical studies.

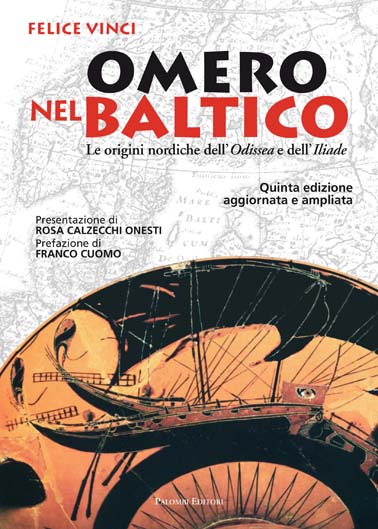

The book suffers from the poor quality of the pictures contained therein. Also, I cannot comment on the conclusiveness of Vinci’s revolutionary thesis. Still, I can appreciate its originality, the personal approach of Vinci when he recalls his journeys throughout Scandinavia, the careful descriptions of the landscapes he visited and their comparison with well-known Homeric places, and the wealth of historical sources cited to support his stance.