Introduction

The Anthropocene confronts people with predominantly man-made problems. On the basis of this realization, it calls on them to change their lives, which goes hand in hand with a resistant change in living habits (Ellis 2020, 24-28). What can be meant by the term resistance? As a working hypothesis for this essay, it is sufficient to define resistant behavior as an active, freedom-oriented and possibly subversive or openly aggressive rejection of repressive, encroaching human behavior on the part of a powerful authority. The philosopher Ernst Bloch names the “duck-mouse” and the opportunist (Bloch 1974, 433) as counterparts of the resistant person, who accept the repressive and violent behavior of other, powerful people for the sake of a “greasy peace” (Bloch 1974, 433). In the 1970s, the psychologist Peter Seidmann attempted to establish a “resistology”, a theory of the evaluation of resistant behavior (Seidmann 1974, 313-315), from the perspective of depth psychology. He tried to prove that resistance must always be judged in terms of responsible ethics. In doing so, he attempted to counter the resistance of the irresponsible neurotic who acts out of a “delusion of salvation and cleansing” (Seidmann 1974, 304) and thus only makes repression even more unbearable under the guise of resistance. Seidmann sees the recognition of human rights as a decisive characteristic of resistance. Resistance has to be learned: as resistance against oppression, resistance has an inherent pedagogical mission according to Paulo Freire: “liberating education” is his keyword here (Freire 1996, 36). However, not much has been achieved with such a formal definition of the concept of resistance. If we look back at the history of resistance, we can identify types of resistance whose structure and individual traits are still very revealing today, especially in the Anthropocene. For the political developments of the European present seem to be pressing:

At a time when military conflicts are once again on the agenda in Europe and when despotic and anti-democratic regimes are behaving in an unrestrained manner and on a global level in a repressive manner towards any form of freedom, it is necessary to take a scientific look at the concept of resistance. This happens unsystematically in everyday reporting. The military and cultural resistance to Putin’s war of aggression against the democratically constituted Ukraine is easy to understand as a resistance of freedom against tyranny. It is more difficult to understand the claim made by the Palestinian Hamas to be a resistance movement (Croitoru 2007, 193) after the completely uninhibited murders, kidnappings and rocket attacks since October 7, 2023.

Many systematic questions need to be asked in view of this situation: Is it compatible with the idea of resistance that the murder of Jews and Israeli non-Jews is seen across the board as a success and a source of pride (Croitoru 2007, 111. 122 and others)? Or is Israel not rather exercising resistance against a global superiority? Further questions follow here: Can militant and media practices of resistance be learned without corrupting the cause of resistance? Is it logically tolerable for resistance to be trained and then exported in countries such as Iran, where even protests of all kinds are violently and autocratically suppressed – as is the case with Hamas (Coitoru 2007, 135)?

In other words, can the type of resistance also discredit the cause and justification of resistance? Is there a legal or moral right to resistance – even against freedom? Is it an option to renounce resistance in favour of a comfortable life? Is there a legitimate form of resistance against the lifestyle of others? What is the relationship between the concepts of resistance and violence? Is climate change a sufficient reason for actions of passive and active resistance? Can we be indifferent to the resistance of others? Is hatred a viable basis for resistance?

Questions such as these make it clear how important the concept of resistance is in today’s everyday media communication and opinion-forming. In addition to these political and cultural issues, resistance practices in other areas of life must also be considered. For example, one can think about forms of economic resistance against the capitalist or state-controlled economy. Practices of resistance are not new in the educational context either. For example, there have always been pupils who have resisted school practices or the content of school lessons.

It can even be seen as part of the school culture to establish resistant practices. Pupils use parodistic practices, for example, to turn against teachers who they perceive as dominant or too tolerant. In this sense, resistance can be seen as a compensatory and, in the best case, innovation-promoting process in the educational context. But even in this sense, it has not yet been possible to generate a productive type of resistant behaviour to a sufficient extent. However, considerable progress has already been made along the way.

Christiane Thompson and Gabriele Weiß, for example, bring together numerous essays in the anthology they edited in 2008 entitled “Widerstände – widerständige Bildung. Blickwechsel zwischen Pädagogik und Philosophie” (Resistance – Resistant Education. An Exchange of Views between Pedagogy and Philosophy), which they edited in 2008, brings together numerous essays that point to the central importance of the term in educational science. Psychological research is also familiar with the concept of resistance. Here, for example, research into resistance to therapies has become increasingly important. In addition, psychological research is also concerned with the causes and consequences of resistant behavior in everyday life and in exceptional political situations. A rather negative concept of resistance seems to prevail in the popular scientific context and in the advice literature (f.ex. Knuf 2018). In the context of company and organizational management, on the other hand, the concept of resistance seems to be viewed increasingly positively as a reason for operational change (Nagel 2021).

However, research in the various disciplines seems to suffer from the fact that very different understandings of resistance exist side by side and that a structural consideration of the phenomenon and the term has not yet been achieved. In view of the significance of resistance, this also appears to be a very extensive undertaking. Seen in this light, this essay can only be seen as a first attempt at a structural systematization. It is not surprising that three historical examples are used here as a starting point for the considerations, all of which can be located in the context of the Second World War. Hardly any other historical context like this has led to a debate on resistance to state violence that is anywhere near as intense and sustained. The historian and demonstrative anti-soldier Carl Erdmann, who was stationed as a German soldier in Italy, Yugoslavia and Albania during the Second World War, is not yet a representative of resistance in the narrow sense. But his recently published notes and the behaviour he documented show how resistant thinking builds on the experience of being reflectively out of place until it brings out resistant traits. More clearly articulated, but based on a similar self-experience, is the attitude of the Danish journalist Vilhelm Bergstrøm. In his case, one can see the gradual development of a new resistant self-awareness in the horizon of journalistic practice and flight. With the third example, the Croatian Jew and resistance fighter Slavko Goldstein, it becomes clear that even a person who basically has no choice but to go to the resistance must move even further into zones of ambivalence.

This can already be asserted on the basis of two very widespread, current comprehensive accounts of the European resistance against Hitler, the overviews Resistance by Halik Kochanski (2022) and “Im Widerstand” by Wolfgang Benz (2018). With regard to this essay, it needs to be explained why three examples have been chosen, all of which are located on the fringes of National Socialist expansion. However, the examples discussed in this essay can easily be linked to one another. They are all located on the borders of the National Socialist empire. As a result, although the repression can be drastic, the alternative, life beyond usurpation, is still within reach in each case. In both cases, the balance of power is also comparatively unstable in comparison to the center of Nazi rule.

Resistance could also count on the support of the population of the occupied or threatened territories, but it was still threatened by ambivalence: the question of the difference between more or less subversive collaboration and more or less effective resistance arose again and again. This could also be expressed as follows: the genesis of patterns of resistance can be studied precisely at the borders of the empire, which are marked not least by the two seas threatened by the Germans in the north and south. The relatively well-researched forms of Italian and French resistance could also be the focus of another, complementary and more comprehensive typological study.

However, it must always be borne in mind that resistance is always a difficult subject of historical research. If it takes place in the repressive context of a regime such as that of National Socialism, resistance often takes place on the basis of spontaneous and very individual decisions (Bosch / Niess 1984, 13). Resistance to Nazi rule seems to have been the concern of sometimes quite ordinary people (Bosch / Niess, 14). Conversely, one could also assume that resistance as a topic is therefore also of interest to everyone today.

The arrangement of the examples follows a logic of escalation. While in the first example it can still rightly be argued whether there is already resistance here, it is clear that at least the path to resistance is not too far away.

The three following case studies can also be seen as attempts to mark the beginnings of resistant consciousness in three selected historical figures. Insofar as one is prepared to accept writing, observing and the willingness to take a personal risk as resistance, then the first two cases can already be subsumed under this heading. In the third case, with Slavko Goldstein, the connection to militant resistance is already clear. However, the first two cases teach us that the emergence of Goldstein’s position of resistance from a personal experience must also be examined more closely.

2. Not yet resistance – but not far from it: the historian Carl Erdmann as a simple German soldier in the former Yugoslavia

Does it make sense to speak of resistance even if the resisting person is part of the army of a repressive occupying power? Can a perpetrator also unconsciously exercise resistance, and if so, how should this borderline case be imagined? The case of the historian Carl Erdmann (1898-1945) is well documented (Reichert 2022a/b) and reveals contours of resistant action and thought in equal measure. On the one hand, he is interesting because of his character disposition. As a scientist who was robbed of his career opportunities by the Nazi regime and the war it instigated, he was not only humiliated in his professionalism. At the same time, he seems to have an unfavourable temper as an interlocutor. Conflicts repeatedly arose in conversations with him, for example with his patron and colleague Paul Friedolin Kehr. And so writes Erdmann’s biographer Folker Reichert:

Erdmann had to apologize because once again he had not been able to rein in his ‘tired habit of always voicing every contradiction immediately’; He was there ‘somewhat impudently’ (Reichert 2022a, 113).

Erdmann is also taking a risk in his assessment of German politics by leaving his circle of acquaintances in no doubt about his opinion of German politics: “[Erdmann] came to the firm conviction that ‘this man [Adolf Hitler] cannot rule us'” (Reichert 2022a, 135).

Erdmann also closely observed the consequences of National Socialist university policy, ultimately seeing himself as its victim. Reichert writes about Erdmann’s observations in the years 1933-1934 as follows:

Erdmann followed the scandalous events [positions of university teachers were filled by NSDAP representatives] to the end, but knew from the first rumors that under these circumstances it would no longer be possible for a scholar to exist at a German university. (Reichert 2022a: 142)

It seems to him that academic intellectuality and National Socialist politics were incompatible in principle. There seems to be another factor regarding the question of Erdmann’s resistance. Erdmann was drafted into military service in the German Wehrmacht in the fall of 1943 at the age of 45 (Reichert 2022a: 14).

Not only his age, but also his skill in practical matters seem to stand in the way of this enlistment. His biographer Reichert emphasizes his military deficits:

[…] Erdmann shot badly and with trembling hands, he failed completely in combat training and was clumsy when cleaning the rifle entrusted to him. […] He was – in his own words – a ‘miserable soldier’, a nuisance to his superiors and a burden to his comrades. […] [Once] because of his unmilitary demeanor in front of the assembled crew, he was insulted as an ‘idiot’ who would have to be court-martialled if he weren’t ‘so stupid’. (Reichert 2022a:15)

As Erdmann’s previous knowledge meant that he was primarily used as an interpreter for Italian (Reichert 2022a: 17), this was of little consequence. In itself, of course, a lack of military aptitude is not a clear indication of resistance. On the other hand, it should be emphasized that Erdmann found the tourist aspects of his stay in Yugoslavia and Albania very gratifying and thus detached himself from the war (Reichert 2022a:20-21). He invested a great deal in learning Albanian – the tenth language he learned (Reichert 2022a: 22-23). This can be understood as an indication that Erdmann may have seen his personal interest in linguistics as a personal constant and resource in a threatening situation. On the other hand, dealing with these languages was also part of his ministry.

As a historian, he repeatedly became an opponent of National Socialist appropriations of historical events and historical figures even before his deployment in the military. In this capacity, he even publicly contradicted the Nazi chief ideologist Alfred Rosenberg and Heinrich Himmler in the only critical academic statement by historians in Germany (Reichert 2023: 367; Reichert 2022a: 231-264). In both cases, it can be said that Erdmann courageously articulated dissent, but that he ultimately did not become a man of resistance (Reichert 2022a: 232). As a historian, Erdmann also wrote a book on the emergence of the crusade idea that is still worth reading and influential today. In it, he emphatically emphasizes the message of love and peace that is fundamental to Christianity (Erdmann 1935/2023:31). The ecclesiastical conception of the crusade idea is therefore ultimately to be understood as its perversion (Reichert 2022a: 122-123). There is thus also a trace in Erdmann’s academic work that points to his negative attitude towards tyranny. This may not be resistance in the narrower sense. But overall, a picture emerges of a resistant person who in a certain way falls out of line, suffers a shift and does not reverse this deviation from expected behaviour. Due to his circumstances, his professional attitude as a historian and his ethos, he moves within the repressive system, first as a young academic and later as a soldier. At the same time, he does not follow the rules of discourse of the Nazi system by publicly taking a stand as a historian against the falsifications of history, as he finds them in Rosenberg and Himmler. He does not become a threat to the system, but with these actions he places himself on the sidelines: a post-collaborative ambivalence arises, which is transformed into resistant dispositions during his deployment in the war.

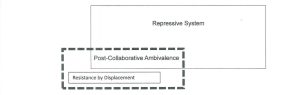

This constellation could be summarized in the following diagram: The field with the solid line encompasses the field of the repressive system of the Nazi state in its totalitarian form. The field enclosed by the thick, dashed line is the space in which Carl Erdmann, who has been pushed into the marginal, symbolically finds himself: beyond the grasp of the state in an ambivalent position, but at the same time, due to his displacement from the state’s sphere of relevance, in a position outside it that can be described as resistant. The element of resistance here is primarily due to a shift that Erdmann could not and did not want to prevent. The case of Erdmann shows in a very impressive way how a person in a zone of ambivalence can approach resistance on the basis of his opinion and his individual disposition. Erdmann did not turn himself into a resistance fighter. But his stigmatization as a non-conformist scientist on the one hand and as an overtaxed soldier on the other set him on a resistant path.

Fig.1.: Situation A: Individual behaviour resembling resistance / resistant character dispositions

3. Resistance and ambivalence of the situation: Denmark in Oktober 1943

If you now look for a historical figure who goes a significant step further in the context of resistance to National Socialism, you may come across the Copenhagen journalist Vilhelm Bergstrøm (1886-1966). He did not engage in violent resistance. However, he set himself the task of documenting the events in occupied Denmark in his diary and thus documenting the existing resistance (Lidegaard 2013:149). Vilhelm Bergstrøm’s resistance during the National Socialist era is more clearly recognizable than in Erdmann’s case. The journalist from occupied Denmark goes a significant step further than the Wehrmacht soldier Erdmann by clearly recognizing his work as a chronicler of events as an act of resistance. This is not only directed against the occupying power, but also against the creation of a legend after the liberation, which he feared, but which was not yet foreseeable. Bergstrøm benefited from Denmark’s special situation during the Second World War, which ensured the continuity of political conditions during the German occupation. Halik Kochanski summarizes this situation as follows:

Denmark had an ambiguous position in German-occupied Europe. It retained its pre-war democratically elected government and its king, Christian X, remained securely on his throne. The Germans deliberately kept their presence at a low level, only guarding the lines of communication to Denmark‘s northern neighbour, Norway. […] There were, however, some Danes who were not satisfied with the comfortable position held by their country in the midst of a brutal world war. (Kochanski 2022: 461)

As a result, a zone of ambivalence emerged in Denmark, which made it the task of the individual to position themselves collaboratively, neutrally or resistively against the occupation. Denmark’s peripheral position in the context of the empire conquered by the Germans should not be underestimated in this situation. The proximity to Sweden made it possible to actively consider the option of fleeing. Even if this was not easy and involved some risks, this option was available to a considerable number of Jewish and non-Jewish Danes. The long crossing from Hellerup in Denmark to Ystad in Sweden, for example, which the Hannover and Marcus families survived, is well documented (Lidegaard 2013: 120. 327-334).

From this perspective, the opportunity to flee across the sea not only enabled the refugees to survive. The survivors’ stories and their perceptions of the occupation and oppression were also preserved. In Sweden, they no longer had to keep anything secret and were able to preserve their impressions of Denmark for posterity. In addition to this archival function, so to speak, Sweden was also important for the resistance in Denmark. On the one hand, Sweden was a country in which the “Danish Brigade” could form as a military and paramilitary resistance organization (Lidegaard 2013: 550). On the other hand, the Swedish government was diplomatically active despite the country’s neutrality, as can be seen, for example, in the case of the so-called White Buses, which were used to evacuate Jews and non-Jews from concentration camps to Sweden (Lidegaard 2013: 533).

Denmark’s peripheral location and the associated maritime proximity to Sweden thus contributed significantly to the development of resistance to National Socialist tyranny, even in its relatively moderate form in Denmark. Vilhelm Bergstrøm was also able to successfully pursue his intention of secretly working on a monumental work (Bergstrøm 2005) about life under occupation (Lidegaard 2013, 336) because Denmark’s specific situation allowed for a wide range of resistance, but also collaboration. The zone of ambivalence was therefore very large here, and it was in this zone that the Danes ultimately had to position themselves.

With his project, Bergstrøm thus embarked on an intellectual, post-factual path of resistance, so to speak, which consisted of documenting the behaviour of others. But the question of the reason for the resistance also arises from his perspective. His work and the actions of his contemporaries observed in it repeatedly refer to the fields of philosophy and anthropology: “Is man basically good but weak? Or are we inherently evil and only held in check by civilization?” (Lidegaard 2013: 541)

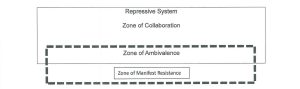

With his decision to document the resistance, however, he takes a position that differs from Carl Erdmann’s unreflected, perpetrator-based and personality-driven resistance in one decisive point: Bergstrøm recognizes the many options of opposing and agreeing from the outside, so to speak. He thus describes the field of resistance as a space of possibility. The diagram of Erdmann’s position (Fig. 1) could be modified in his case, and thus for the situation of the Danes, as follows:

Fig.2.: Situation B: Ambivalence, collaboration, resistance and damage control (Denmark, France)

Situation B is significantly more complex than situation A. And it is so simply because resistant action is recognized as systematically conditioned by the situation. The situation in Denmark allows those who are considering resistance as an option for action to switch between the different zones for reasons of camouflage and security or to stay in different zones at the same time. Significantly, the different ways of expressing resistance or consent basically allowed every Dane to participate in resistance in some form. As late as 1964, Hannah Arendt said that the Danes were the only ones who dared to openly oppose the occupying power (Arendt 1990: 290). The opposition to the Germans’ anti-Semitism was also successful and led to significant changes in the occupying forces’ behavior (Lidegaard 2013: 543).

Of course, much more could be said here about the Danish resistance. In the course of this, one would also have to address the proximity to Norway, already alluded to in Kochanski’s quote, in which the resistance had to unfold in a completely different way. The situation there could be developed into an independent model of resistance as a contrast to the Danish situation. It is even possible that the situation there is more similar to the conditions in Croatia, which will be explored below on the basis of Slavko Goldstein’s life in the resistance.

4. Resistance in a hyper-complex system of heteronomy: Slavko Goldstein

The Croatian Jew Slavko Goldstein is chosen here as the third example of a structurally interesting type of resistant person. This brings us back to the Mediterranean in the logic of this essay. The situation in the Balkans during the German and Italian occupation during the Second World War is much more complex and also much more violent than in the first two examples. While the Danes were largely able to maintain their political system and see their national identity politically anchored to a certain extent, the Nazis installed a vassal in Croatia in 1941, Ante Pavelić, who developed a Croatian form of fascism and thus largely accommodated the occupiers. While in Denmark the population openly or covertly turned against the German occupiers, in Croatia they cheered the occupying power because they hoped it would lead to their own independence (Matzower 2009: 322).

However, this state, which then unfolded in a reign of terror by the ultranationalist Ustaše led by Pavelić, was completely unacceptable, at least for Croatian Jews, but also for many other Croats. However, the situation in 1943 was not only that a separate, Croatian form of repression was established alongside the repression by the occupying power. The resistance did not simply have to turn against the occupation, but against its own countrymen, which made the situation much more complex. Unlike in Denmark, the population is ultimately divided when it comes to opposing the resistance. Resistance against the occupying power also appears obsolete in the historical situation around 1943, as most people in the resistance expected the Germans to be defeated and the overriding problem was therefore the threat of civil war:

There was a real danger that civil war would take precedence over resistance to the Germans. […] The resistance in the Balkans expected an Allied invasion, as indeed did the Germans. When the BLO [British Liaison Officers] made it clear, that no such invasion would take place, it appeared to the various resistance movements that there was little point in taking casualities by fighting the Germans when there were internal enemies to be conquered. (Kochanski 2022: 474)

The work and thoughts of Slavko Goldstein (1928-2017) should be seen in this context. As the son of a Jewish-Croatian bookseller, he experienced the rule of the Ustaše as extremely violent, arbitrary and particularly threatening for him as a Jew. His father was sent to the Danica concentration camp, which had existed since 1941 and in which mainly Serbs, but also Jews and opposition Croats, were imprisoned (Goldstein 2018: 56). He was murdered in the Jadovno camp in July 1941 under circumstances that are no longer entirely clear (Goldstein 2018: 272). Step by step, his son Slavko Goldstein’s life was made more difficult, the bookshop was finally expropriated, but Slavko and his mother managed to maintain a personal connection to it through a ruse (Goldstein 2018: 195-209). Slavko Goldstein joins the resistance after the many humiliations he experiences as a Jew and son of a communist and eventually becomes part of Tito’s partisan army (Goldstein 2018: 496). He not only saw this as the only army in which “Croats and Serbs fought on the same front” (Goldstein 2018: 501), but in which he was also accepted as a communist and a Jew. Looking back, he sees the dark sides of Tito’s partisan army quite clearly and with reflection (Goldstein 2018: 502).

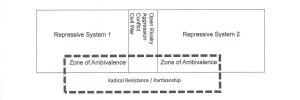

For a systematic consideration of his resistance situation, it should be noted that the third type of resistant action must unfold within at least two repressive reference systems. These are in a physically and symbolically aggressive conflict. Due to this rivalry, the person of resistance is trapped in zones of ambivalence in their everyday life and must relate to them – for example by acting covertly or by being forced to take a clear position. Of course, resistance here depends on how the conflict between the rival systems plays out. In predominantly military rivalries, the person of resistance is a partisan; in symbolic conflicts, for example, he is an intellectual who attacks the symbolic systems.

Fig. 3.: Multidimensionaler Widerstand in komplexen Repressionssystemen (Slavko Goldstein)

Slavko Goldstein is very different from Erdmann and Bergstrøm in terms of the resistance they offer. On the one hand, like Erdmann, he is not forced into passive resistance, so to speak, because he could not be on the side of the perpetrators simply because of his Jewish origins. Similar to Erdmann, however, he is, so to speak, passively pushed into the resistance due to his personal dispositions and his family and political background. The comparison with the situation in Bergstrøm is also interesting. As a journalist and chronicler of the time of German occupation, Bergstrøm documents life under German occupation and the diverse actions of the resistance with a view to the yet-to-be liberation. Goldstein was only able to comment autobiographically on the resistance long after the end of the Second World War.

His situation is highly complex: even in Tito’s Yugoslavia, whom he initially supported at the risk of his life, he quickly becomes a dissident and has to fear for his civil existence. He criticizes Tito’s seizure of power in detail in 35 points and contrasts it with the original concern of the resistance (Goldstein 2018: 502-535). In contrast to Bergstrøm, the resistance’s concern with liberation has not yet been realized. In Goldstein’s case, the retrospective develops into a form of reflection that not only implies an insight into the limits of resistant action, but also leads to basic existential insights. In some places in his autobiography, his retrospect seems almost a little resigned when he writes as follows:

[…] There are moments, even whole periods of life, when our existence is in the hands of other people. Then someone decides relentlessly about us, without us being able to defend ourselves. We can only flee or resign ourselves to the course of life […] Looking back, I tried to understand where the evil that happened to us came from. […] I didn’t get an answer that explained everything, because there definitely isn’t one. But in retrospect I understood the mechanism of evil at that time a little better. (Goldstein 2013: 97)

Seen in this way, his example makes it clear that resistance does not automatically have to end in triumphalism after overcoming what the resistance is against. For Slavko Goldstein, resistance was ultimately a life issue. This could also be the case in a successful and insightful way because he was prepared to question the resistance even after the fact and thereby clarify the issue against which exactly the resistance was directed. This retrospective reflection relating to the present becomes particularly clear in the passage quoted. For Goldstein, there is no “answer that explains everything”. Resistance therefore remains a life impulse that cannot come to an end and yet must be reconciled with biography. Seen in this way, Goldstein indicates a form of resistance that retains a high degree of complexity due to the complex situation in which it emerged and is therefore also highly philosophically reflected. Resistance on the basis of his humanistically oriented Judaism is therefore a life theme that must biographically integrate with other life themes. While for Erdmann the unsystematic but sincere resistance behaviour ultimately causes the biographical decline and the end of his civil life, for Bergstrøm and many other Danes it establishes a new form of self-assertion, for Goldstein it is the overall existential situation that is caused by the resistance a complex situation, particularly clear.

Conclusion

Even if the three cases of resistant action that are at the centre of this article should not be compared with each other historically or played off against each other, it is clear that there is a lot to be learned from them as case studies of the structural diversity of resistant action. Resistance cannot therefore be separated from the biographical work of individual people, even in politically and militarily explosive situations. The decision to go into resistance seems to depend heavily on the context of oppression. With regard to the present essay, it has proven particularly helpful for structural analysis to go to the fringes of a major conflict, for example the Second World War, in search of examples of resistant action, in order to stimulate a typology of the resistant and resistance.

This could allow us to describe and assess resistant actions in politics and pedagogy in a pointed way. In the long term, this could limit misuse of the concept of resistance and perhaps also identify new forms of resistance. There is still a lot to be done here, because addressing resistance will also meet with resistance.

And the Anthropocene?

Slavko Goldstein himself wrote his biography, first published in 2007, in the era of the Anthropocene. At the end of his book, he emphasizes as a lesson from his life “that doubt is not an unforgivable weakness, but a necessary rebellion against fatal convictions” (Goldstein 2013: 575). Goldstein’s book itself describes the laborious path from a fatalistic attitude, which sees the German occupation as a fateful and unavoidable destiny (Goldstein 2013: 13), to an emancipated, resistant attitude, which is also developed at the risk of one’s life. Essentially, Erdmann and Bergstrøm are also following the same path, albeit under very different conditions and on the basis of different character dispositions and thought prerequisites. In this path, there is a possibility of analogy formation. Eva Horn and Hannes Bergthaller provide an indication of this when they write: “Thinking the Anthropocene means thinking along fault lines, tensions and contradictions” (Horn / Bergthaller 2019: 219).

It is precisely this kind of thinking that can be learned from the three people presented in this essay – and even more. All three show that resistance to fateful threats must also be developed and unfolded in people themselves, in their attitudes and practices. Those who engage in resistance must first be able to experience themselves as resistant subjects, so to speak, must be able to grant themselves the human right to resist in order to become resisters. Resistance in the Anthropocene is more than just the appropriate management of undesirable climate impacts; it has an implicit subject-philosophical and subject-cultural aspect.

Literature

Arendt, Hannah (1964 / 1990): Eichmann in Jerusalem. Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen, aus dem Amerikanischen von Brigitte Granzow, mit einem einleitenden Essay von Hans Mommsen, Leipzig: Reclam.

Benz, Wolfgang (2018): Im Widerstand. Größe und Scheitern der Opposition gegen Hitler, München: Beck.

Bloch, Ernst (1970): Widerstand und Friede. In: Politische Messungen. Pestzeit, Vormärz, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, S. 433-445.

Bosch, Michael / Niess, Wolfgang (eds.) (1984): Der Widerstand im deutschen Südwesten 1933-1945, Schriften zur politischen Landeskunde Baden-Württembergs Bd. 10, Stuttgart et al. : Kohlhammer.

Bergstrøm, Vilhelm (2005): En borger i Danmark under krigen : dagbog 1939-45, udgivet af John T. Lauridsen, Kopenhagen: Gad.

Croitoru, Joseph (2007): Hamas. Der islamische Kampf um Palästina, München: Beck.

Erdmann, Carl (1935 / 2023): Die Entstehung des Kreuzzugsgedankens, mit einem Nachwort von Folker Reichert, Darmstadt: WBG.

Evans, Richard J. (2010): Das Dritte Reich. Band III: Krieg, aus dem Englischen von Udo Rennert und Martin Pfeiffer, München: DTV.

Freire, Paulo (1996): Pedagogy of the Oppressed, translated by Myra Bergmann Ramos, London: Penguin.

Goldstein, Slavko (2007/ 2018): 1941. Das Jahr, das nicht vergeht. Die Saat des Hasses auf dem Balkan, aus dem Kroatischen von Marica Bodroži, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

Horn, Eva / Bergthaller, Hannes (2019): Anthropozän zur Einführung, Hamburg: Junius.

Knuf, Andreas (2018): Widerstand zwecklos. Wie unser Leben leichter wird, wenn wir es annehmen, wie es ist, 2. Auflage, München: Kösel.

Kochanski, Halik (2022): Resistance. The Underground War in Europe 1939-45, Dublin: Allen Lane.

Lidegaard, Bo (2013): Die Ausnahme. Oktober 1943: Wie die dänischen Juden mithilfe ihrer Mitbürger der Vernichtung entkamen, aus dem Englischen von Yvonne Badal, München: Blessing.

Lundtofte, Erik (2005): https://www.historie-online.dk/boger/anmeldelser-5-5/besaettelsen/en-borger-i-danmark-under-krigen

Mazower, Mark (2009): Hitlers Imperium. Europa unter der Herrschaft des Nationalsozialismus, aus dem Englischen von Martin Richter, München: Beck.

Mihai, Mihaela (2022): Political Memory and the Aesthetics of Care, Stanford University Press.

Möller, Lenelotte (2017): Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus. Von 1923 bis 1945, 2. Auflage, Wiesbaden: Marix.

Nagel, Erik (2021). Glücksfall Widerstand. Vom produktiven Umgang mit ganz normalen Ausnahmen, Zürich: Versus.

Reichert, Folker (2022a/b): Fackel in der Finsternis. Der Historiker Carl Erdmann und das ‚Dritte Reich‘, Band 1: Die Biographie; Band 2: Briefe 1933-1945, Darmstadt: WBG Academic.

Reichert, Folker (2023): Nachwort zur Neuausgabe. In: Erdmann, Carl (1935 / 2023): Die Entstehung des Kreuzzugsgedankens, mit einem Nachwort von Folker Reichert, Darmstadt: WBG, p. 365-377.

Seidmann, Peter (1974): Der Mensch im Widerstand. Studien zur anthropologischen Psychologie, Bern: Francke.

Thompson, Christiane / Weiß, Gabriele (2008): Zum Widerständigen des Pädagogischen. In: Thompson, Christiane / Weiß, Gabriele (Ed.): Bildende Widerstände – widerständige Bildung. Blickwechsel zwischen Pädagogik und Philosophie, Bielefeld: Transkript, p. 7-22.