In 1965, Singapore achieved independence after being expelled from the Federation of Malaysia. Having no natural resources and being one of the smallest countries in the world, Singapore had to shape itself as a State, regional and global player in order not to become, like most micro-states, gobbled up by expanding, neighboring states, or an inaudible voice and non-existing international diplomatic and political structures[1]. To do so, Singapore saw the action of a team led by one man that directed the country for 25 years, shaped its political system, diplomacy, economy and society: Lee Kuan Yew[2]. But to understand Singapore, we must understand its unique conditions that led to a unique economic, political, diplomatic and social system that drove its survival and, later, prosperity.

Singapore: an “Independent Gibraltar” in Asia

From its British colonial past, Singapore inherited the title of “Gibraltar of the East”, an analogy based on geographic, strategic and commercial features both cities enjoy[3]. However, Singapore is an independent country which had to reinvent and adapt itself to a new rising international order, being in a difficult region at the time (and still today): there was war in Vietnam, Communism in Cambodia and China, unstable political and religious conditions in Indonesia, and the United States’ military presence in the region. In order to survive in such a regional context, Singapore crafted what I will call its “Singaporean Survival” philosophy adopting national and diplomatic core values[4]:

- Successful and Vibrant Economy: How?

- Not Being a Vassal State: Why?

- Friendly to All, Enemy of None: Who?

- Global World Governed by the Rule of Law and International Norms: Where and How?

The first core value may be considered as a “How?” in the international relations analysis of the “Singaporean Survival” philosophy. It is the means for Singapore to achieve primary survival as a sovereign nation, ensure an income and opportunities for its inhabitants, as well as ensuring an economic income for the national government with the goal to secure a political system to run the country. The second core value may be considered as a “Why?”, as it reflects Singapore’s fears driven by the concept of Westphalian Statehood: not having full sovereignty within its borders and not having a strong international status. It is a fear driven by the fact that Singapore is a small nation without resources, and with a small population[5], meaning it would be relying on other countries to secure its status as a microstate. The third is a “Who?” in the sense of identity. Singapore had to shape itself as a nation, implying the creation of an international identity that would fit its regional geopolitical context and thus avoiding conflict, as it would not be strong enough to be an international military power. Furthermore, this approach helped Singapore in cooperating with everyone and then shape economic partnerships. It is a barrier-free approach to Liberalism. However, Singapore does not want to have friendly relations at any cost as its primary interest is its own security[6]. Finally, the fourth component is a “Where and How?”. This last point reflects Singapore’s ambition to promote freedom and stability to strengthen its image as a safe State willing to play by the rules. In this sense, this core value shows Singapore’s faith in peace and international cooperation, promoting international institutions as the primary international rule to avoid conflicts of interest by promoting the common international rules for all states and not a particular foreign state’s philosophy.

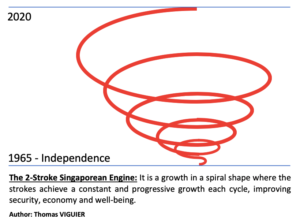

Singapore and International Relations Theories: the 2-Stroke State

Singapore created, through its philosophy, a development structure for its small nation, in which we may identify several points:

From Independence to Security and Stability:

As a small State, Singapore may not be able to compete with other States in terms of military capacity and technology, being rapidly outnumbered and outpowered by larger States due to its relatively small population (around 5,7 million people), small territory and therefore limited natural resources. This implies that the realist definition of power given by Waltz: “size of population and territory, resource endowment, economic capability, military strength, political stability and competence”[7] is overall not favorable to Singapore. This means that Singapore had to find new ways of asserting power while still developing such traditional fields with the development of an army, the implementation of compulsory military service and a constant progression towards cutting-edge military technology[8]. Therefore, Singapore achieved a version of soft Realism to achieve a primary survival: despite being small and limited in resources, be consistent, trustworthy, competent, stable politically, and keep asserting your position in the world as a state[9]. By recognizing its own features and the regional context in which it had to develop itself, Singapore accepted the vision of chaos and State-driven interests, starting with its own[10]. This Singaporean approach targeted the promotion of national wealth through the development of international cooperation where Singapore would play a key role, trying to be a “necessary, competent and wealthy” actor on the international scene. In this sense, the goal was the creation of a strong economy and then transition towards a more liberal approach. The process was a 2-step one: first reaching security, stability and international recognition, and then reaching sustainability and prosperity by using its key status to continue running its economy. I will call this process the 2-Stroke Singaporean Engine: 2 strokes that complement each other and meant to keep the Singaporean ball of survival rolling while increasing its wellbeing, international high-level status as an untouchable state, and therefore security. A philosophy marked by a progressive mix between realism (dominant at the beginning of Singapore’s history for its own survival) and liberalism (a philosophy progressively introduced over time). In this sense, Lee Kuan Yew’s approach to Realism and political stability was based on a hybrid regime[11] with a dominant – party system, a political system that still continues today. This political system would help in controlling all aspects of the State’s development without contestation, building continuity within government policies and society, with strong measures such as implementing compulsory military service to raise an army and to limit freedom of press[12]. In this sense, the shift from Realism to Liberalism is the first of the 2-Stroke Singaporean Engine: materialization of national effort to secure the international position of the State in a chaotic region with almost no natural resources but with a high strategic geographic position.

From Security and Sustainability to Sustainability and Prosperity:

The implementation of a strong liberalist approach to economy mixed with an institutionalist perspective[13] is the second stroke, where Singapore increases its liberal approach by creating and promoting all the required frameworks and values to enhance its economy and take the most out of it[14], frameworks based on the analysis of foreign countries and international companies’ policies[15]. However, the second stroke is still based on soft Realism, where Liberalism plays a stronger role of catalyst than traditional realist concepts of power such as military strength by achieving economic capability and, to some extent, competence. In this sense, Singapore has secured its survival and stability, starting then the building of a wealthy nation that is meant to be a model of sustainability and prosperity, attracting two of the core values promoted by Liberalism: investment and free trade. Singapore progressively achieved this shift, notably with the creation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967[16] and its membership to the General Agreement on tariffs and Trade in 1973 (that would become later the World Trade Organization in 1995)[17]. Therefore, Singapore is promoting a very aggressive form of Liberalism and Pragmatism[18], supported nationally by a hybrid political regime that is still meant to achieve, at the same time, a soft form of Realism. An example and cornerstone of Singapore’s success may be the creation of the Economic Development Board in 1961, which laid the foundations for the economic development of Singapore through industrialization and the import of high-level engineering skills[19]. Therefore, this soft form is diversified in terms of tools used to achieve prosperity while serving the purpose of strengthening constantly the state of security, such as the production of high-level technology and the concentration of financial services and institutions, generating therefore economic, social, industrial and ultimately geopolitical stability for the benefit of all actors connected to the country.

Overall, with this second stroke, Singapore means to increase its wealth and develop its nation, capacity, resources and international gravitas, not forgetting to improve its own security at the same time. In this sense, the second stroke achieves a shift in terms of priorities, in which economic, diplomatic, technological and social development are the first goal, serving at the same time the purpose of security as a secondary but not so far away goal.

Friendly to All, Enemy of None: Is Singapore the Maximum Exponent of the Democratic Peace and Regime Theory?

Singapore’s international approach to diplomacy is mainly cooperative and peace-focused[20]. Despite its larger GDP[21], stronger military alliances (with the US for example) and technological development, Singapore remains a small city-state facing bigger neighbors in case of conflict. Therefore, Singapore developed an international diplomatic policy of “Friendly to All, Enemy of None”[22] to survive as a micro-state in the international scene. This policy might be compared to the democratic peace theory as it promotes a peaceful relationship between Singapore and its regional belligerent and bigger neighbors such as Malaysia and Indonesia[23]. In order to be successful, and not being a full-scale democracy (hybrid regime) by itself, Singapore adopted a dyadic approach to the democratic peace, making no difference between democratic and non-democratic States in its diplomatic and economic relations[24].

However, it can be argued that Singapore, as a hybrid regime, may not be associated with the concept of Democratic Peace. Despite such feature, Singapore still represents, in many aspects, a credible and successful representative of the Democratic Peace. Going further, the country represents a true alternative in terms of governance, stability, prosperity, international relations, social and economic development. In this sense, the country tops the world ranking highlighted in the Global Competitiveness Report from the World Economic Forum since 2019, in which metrics such as health, infrastructures, environment, institutions, skills, education, employment conditions and workers’ rights play a prominent role in evaluating the country’s economy[25]. Therefore, it can be argued that despite being a hybrid regime with a dominant – party syndrome, Singapore is performing pretty close to, or even better than, traditional democracies, as highlighted in the Global Competitiveness Report 2019. This implies that Singapore’s government succeeded in building a strong, stable, sustainable and prosperous country despite being a dominant – party system.

In this sense, despite the political sacrifice of democracy as a cost of opportunity, this effort has been materialized in a successful and innovative model, in which the People’s Action Party (PAP) plays the dominant political party building governmental authority, stability and consistency. Therefore, Singapore’s representation of the Democratic Peace may be justified by the fact that the PAP appears to be largely approved by Singaporeans, as the party won the 2020 general elections[26]. Nevertheless, it may be argued that Singapore is not a democracy and thus the elections may be flawed. However, it is harder to argue Singapore’s success since its independence, outperforming regional and international competitors, leaving a clear legacy and an existential question for other countries: “What is the ultimate purpose of government?”[27].

In this sense, as the goal was to achieve survival and reach a minimum level of security, Singapore’s government efforts were oriented towards the creation of stability and make use of opportunities and commonalities between states to create a fruitful cooperation. The country was ultimately showing to the World that it is safe and profitable to work with them, despite being an atypical country in many aspects above-mentioned.

This perspective is strengthened by the fact that Singapore has shown a strong belief in and commitment towards international institutions, building supra-national protection against its more powerful partners and bringing the necessary stability its cooperation agreements needed to survive[28]. But not confident in its militarily weak situation in Southeast Asia, Singapore nuanced its liberal policy with a strong realist component: military cooperation with the US. In this sense, Singapore is friendly towards the US, perhaps in an attempt of applying the shelter theory, and is definitely frustrating any regional threat to its sovereignty[29][30]. It is a double protection in the end: an economically “necessary” partner and protected militarily by a superpower.

Singaporean Geopolitical Pillars

To understand what the Singaporean interest in the Arctic would be, four geopolitical pillars have been identified: Geography, maritime sector, financial sector, and education sector. Singapore is located right in a key junction of the main international sea routes between Asia and Europe: Malacca. Being the shortest passage for maritime routes between East Asia and Europe, Malacca is a heavy traffic and maritime strategic area as well as a converging point between the Andaman Sea (Indian Ocean) and the South China Sea[31]. The development of harbor facilities, bunkering and a friendly policy towards shipping positioned Singapore to get the most out of its geographic location: becoming a key harbor within the main trade routes as it provides all the shipping-related services before entering the Indian Ocean or the South China Sea[32]. Furthermore, the maritime sector is vital for the country as it allows its industrial and manufacturing sectors to continue developing as it is an important logistic factor for exports and imports. Alongside the maritime sector, which constitutes up to 7% of its GDP[33], the financial sector was developed with tax-friendly policies to attract foreign investments[34]. This policy would bring another nickname for Singapore: the Switzerland of the East[35]. Bank secrecy and favorable tax policies, in addition to its neutrality and stability, would lead Singapore to become a central marketplace and one of the most economically competitive countries in the world[36]. But Singapore did forecast future trends and saw that its citizens would have to follow the country’s growing path, realizing as well that a highly educated population would represent a strong asset to further development of the country. Education was a central social component of the State’s social policy, increasing its budget every year and considerably (up to 70% increase between 2007 and 2018)[37]. It is a way to mitigate or “compensate” the regime theory approach to State, so population would not feel being apart and ignored totally. We may find points of comparison with the famous Roman “Panem et Circenses” (Bread and Circus), best analyzed by Fyodor Dostoevsky in his poem “The Grand Inquisitor”, in which he describes how persons may bow down to the person who will give them bread[38]. However, seduction of mind may constitute a barrier to this “power” given by bread, but Singapore has found the way to achieve both: ensure social security and prosperity (bread) and promote opportunities and provide a strong international status to its citizens[39].

Global Role Translated in Arctic Affairs

Therefore, what are the possible interests of Singapore in the Arctic? According to the previous short analysis, and in light of the recent developments in the Arctic (e.g., the increasing in traffic and tonnage on the Northern Sea Route[40]), we may identify three main fields of interest: diplomacy, shipping and natural resources. As it has been highlighted, Singapore heavily relies on maritime industries. As the Arctic routes represent a strong alternative (despite being still under development and facing great challenges), they constitute a direct threat to the traditional maritime routes passing via Singapore[41]. In this sense, there won’t be a total shift of traffic from these Southern routes to the Arctic ones, as East Asia is still connected to other Southern regions that will continue passing through Malacca Strait: the Persian Gulf and the oil fields; India; Africa; Eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea; etc. In addition, not all companies might be willing to upgrade their fleet, which is very expensive (upgrade to or acquisition of Ice-Class vessels, compliance with the Polar Code, subscribing to particular insurances for Polar waters, paying the Russian fee for the Northern Sea Route, etc.), and may decide to continue sailing the controlled and mastered Southern routes. But Singapore has a long-term economic policy in which it tries to forecast all trends and diversify its assets[42]. In this approach, Singapore follows the move towards the Arctic, where high level investments are required and where opportunities and empty seats are still available. Russia is in need of foreign investments for its mega projects on natural resources (e.g., Yamal LNG and Arctic LNG 2 have French, Chinese and Japanese investments[43]) and for developing infrastructures such as bunkering, harbors, shipyards and trade centers, features in which Singapore is specialized. We may notice the presence of the largest Asian maritime stakeholders like China, Japan and South Korea in such projects (e.g., South Korean Samsung Heavy Industries signed a partnership with Zvezda Shipyard in Bolshoy Kamen, Eastern Russia to develop Arctic shipbuilding[44]), having developed an official Arctic policy[45]. But Singapore has, probably in its flexible and “Friendly to All” policy, not issued an official policy yet, but has developed structured and recognized by the Arctic Council strong diplomatic ties.

However, it is participating actively within the Arctic Council’s Working Groups, as this is the main entrance door for Observers to Arctic Affairs[46]. It demonstrates that Singapore is seeking to strengthen its actions in the Arctic as a future trade place for natural resources (according to a US Geological Survey report, large reserves of oil, gas and minerals are untapped in the Arctic[47) and as a future maritime transit passage. Singapore has developed, in its attempts to reach sustainability and prosperity, education and essential diplomatic, maritime and financial positions that have been the key to be part of large international ventures. The approach to the Arctic is no different. In this sense, Singapore may bring via the Arctic Council’s Working Groups its knowledge power (experience, expertise and education) as a diplomatic way, and its financial and industrial expertise through the private sector for economic ventures. The lack of information regarding Singapore’s moves in the Arctic might be attributed to the geopolitical challenges linked to the region, where its two main partners are in an open front: China and the US (e.g., the construction of airports in Greenland[48]). We might then raise awareness on the Singaporean diplomatic policy: will the Friendly to All survive to the Arctic tensions? Will Singapore be able to keep its neutrality if its steps in Arctic diplomacy and industry? As many Asian countries, governments may issue interventionist policies for their private sector (e.g., the South Korean government urged the merger between Samsung and Daewoo Heavy Industries shipyards[49][50]) to maintain international competitiveness. Singapore is much of the same. Moreover, as a supporter of the regime theory with a dominant – party syndrome, it is known to be highly interventionist[51].

Furthermore, Arctic challenges stress Singapore’s adaptability skills. Its natural economic, political and geopolitical environments are strongly linked to its Asian geography. As a region dominated by sovereign states (which apply a strict Westphalian conception of state and a hard realist approach in the Arctic[52]), the Arctic will oblige Singapore to walk on a thin line between the two facing blocs if it is willing to cooperate on Arctic affairs: East and West. As a regional economic power in Asia, Singapore might be pushed by its neighbor China to take its side, but the US might be willing to see Singapore as an ally or, at least, to continue being neutral economic and diplomatically. However, Singapore may find diplomatic ties in more neutral Arctic States such as Norway or Finland, States that have been through the Cold War and survived to the East-West tensions adopting specific diplomatic approaches such as the Nordic Peace for Norway[53].

Conclusion

Singapore has crafted, applied and enhanced a successful economic, political and social model over the decades to reach the top of the ranking in terms of economy, international influence and wellbeing. Despite the nuances between its national interventionist and regime theorist policy, and its ultra-liberalist international approach, Singapore faces the greater challenge of reinventing itself. Furthermore, a progressive shift of the maritime sector to the Arctic might engage a third stroke in the Singaporean Engine. However, this economic shift is implying a geopolitical shift in its international relations and to adapt to Arctic diplomacy and the emerging opportunities. In this sense, Singapore will play in the same arena as its two major partners: the economic China and the military US. Nonetheless, the past ghosts of the Cold War are reappearing: nuclear accident in the Russian Arctic in 2019[54], China – US confrontation in Greenland[55], progressive military build-up in Russia[56], aggressive Chinese Arctic policy[57], tensions around Svalbard between Russia and Norway[58], to name but a few. In this sense, some of these Arctic challenges and issues may highly benefit from the Singaporean diplomatic and pragmatic approach, giving to Singapore a chance to promote itself as a problem solver. However, Singapore has to find its narrow line to steer gently across the geopolitically stormy Arctic, avoiding losing its neutrality, promoting cooperation and taking the most out of the new markets and economic opportunities. To do so, Singapore may apply to Arctic affairs its savoir-faire and promote its own philosophy through its neutral economic and diplomatic approach, avoiding falling into taking part in geopolitical issues that might have repercussions back in Asia. As a successful path forward in a conflictive region, Singapore represents a lighthouse that may be used in order to navigate the harsh Arctic affairs conditions: avoiding escalation, advancing stability, and ultimately promoting new ways for all States to follow a peaceful cooperation with mutual benefits and respect in the Arctic.

References

[1] Archie W Simpson, ‘Revisiting the United Nations and the Micro-State Problem’ International Relations 8.

[2] ‘Lee Kuan Yew | Biography, Education, Achievements, & Facts’ (Encyclopedia Britannica) <https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lee-Kuan-Yew> accessed 14 May 2020.

[3] ‘Battle of Singapore | Infopedia’ <https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/infopedia/articles/SIP_2013-07-19_113523.html> accessed 14 May 2020.

[4] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (CNA) <https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/singapore/full-speech-vivian-balakrishnan-highlights-principles-9038582> accessed 14 May 2020.

[5] OECD, Southeast Asian Economic Outlook 2013: With Perspectives on China and India (OECD 2013) 191 <https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/southeast-asian-economic-outlook-2013_saeo-2013-en> accessed 14 May 2020.

[6] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[7] ‘Comparing and Contrasting Classical Realism and Neorealism’ <https://www.e-ir.info/2009/07/23/comparing-and-contrasting-classical-realism-and-neo-realism/> accessed 26 May 2021.

[8] Ratnam Saravanan, ‘SHOULD THE SINGAPORE ARMED FORCES CONTINUE TO RELY ON CUTTING-EDGE TECHNOLOGY?’.

[9] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[10] The regional chaos generated by different political movements opposed and in war with both the Malaysian and Indonesian central governments (such as the Second Malayan Emergency 1968 – 1989, the invasion and occupation of East Timor by Indonesia 1975 – 1999 and the still ongoing Papua Conflict which opposes Indonesia to the Free Papua Movement since 1962) deviated these countries’ attention from Singapore’s independence and development.

[11] International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, The Global State of Democracy 2019: Addressing the Ills, Reviving the Promise (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2019) 167 <https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/global-state-of-democracy-2019> accessed 14 May 2020.

[12] ‘Singapore : An Alternative Way to Curtail Press Freedom | Reporters without Borders’ (RSF) <https://rsf.org/en/singapore> accessed 14 May 2020.

[13] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[14] ibid.

[15] Jon ST Quah, ‘Why Singapore Works: Five Secrets of Singapore’s Success’ (2018) 21 Public Administration and Policy 5, 15 <https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/PAP-06-2018-002/full/html> accessed 30 September 2020.

[16] ‘ASEAN’ <http://www.mfa.gov.sg/SINGAPORES-FOREIGN-POLICY/International-Organisations/ASEAN> accessed 26 May 2021.

[17] ‘WTO | Singapore – Member Information’ <https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/singapore_e.htm> accessed 26 May 2021.

[18] Quah (n 15) 6.

[19] ‘Transforming Landscapes, Improving Lives: 50 Years of Economic Development’ <https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/transforming-landscapes-improving-lives-50-years-of-economic-development/story> accessed 26 May 2021.

[20] ‘MINDEF Singapore’ <https://www.mindef.gov.sg/web/portal/mindef/defence-matters/defence-topic/defence-topic-detail/defence-policy-and-diplomacy> accessed 14 May 2020.

[21] ‘Singapore Economy’ (Base) <http://www.singstat.gov.sg/modules/infographics/economy> accessed 14 May 2020.

[22] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[23] ‘The Indonesian Confrontation 1962 to 1966 – Anzac Portal’ <https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/indonesian-confrontation-1962-1966> accessed 26 May 2021.

[24] ‘Democratic Peace | Political Science | Britannica’ <https://www.britannica.com/topic/democratic-peace> accessed 26 May 2021.

[25] Klaus Schwab, ‘The Global Competitiveness Report 2019’ (World Economic Forum 2019) 506–509 <http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TheGlobalCompetitivenessReport2019.pdf>.

[26] rosamir, ‘SINGAPORE 2020 GENERAL ELECTION: The Results’ (The Straits Times, 11 July 2020) <https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/2020-general-election-the-results> accessed 26 May 2021.

[27] Graham Allison, ‘Lee Kuan Yew’s Troubling Legacy for Americans’ (The Atlantic, 30 March 2015) <https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/03/lee-kuan-yew-conundrum-democracy-singapore/388955/> accessed 26 May 2021.

[28] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[29] ibid.

[30] Prashanth Parameswaran, ‘Army Exercise Puts US-Singapore Defense Ties into Focus’ <https://thediplomat.com/2019/07/army-exercise-puts-us-singapore-defense-ties-into-focus/> accessed 15 May 2020.

[31] Xiaobo Qu and Qiang Meng, ‘The Economic Importance of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore: An Extreme-Scenario Analysis’ (2012) 48 Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 258 <https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1366554511001104> accessed 26 May 2021.

[32] ‘Why Is Singapore Port so Successful? A Look at World’s Top Shipping Centre’ (Ship Technology, 24 October 2019) <https://www.ship-technology.com/features/why-is-singapore-port-so-successful/> accessed 14 May 2020.

[33] ‘The Establishment of Maritime Singapore Ecosystem’ (Maritime Singapore) <http://www.maritimesingapore.sg/about-maritime-singapore/> accessed 14 May 2020.

[34] ‘Singapore Tax Rates, Tax System, Tax Incentives – 2020 Guide’ (CorporateServices.com) <https://www.corporateservices.com/singapore/singapore-tax-system/> accessed 14 May 2020.

[35] ‘Singapore, “Switzerland of the East”’ The New York Times (21 January 1973) <https://www.nytimes.com/1973/01/21/archives/singapore-switzerland-of-the-east.html> accessed 14 May 2020.

[36] Schwab (n 25).

[37] ‘MOF | Singapore Budget 2020 | Government Spending On Education And Healthcare’ <https://www.singaporebudget.gov.sg/budget_2020/about-budget/budget-features/govt-spending-on-education-and-healthcare> accessed 14 May 2020.

[38] ‘11. Dostoevsky.Pdf’ <https://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil100/11.%20Dostoevsky.pdf> accessed 14 May 2020.

[39] ‘Full Speech: Vivian Balakrishnan Highlights Principles Underpinning Singapore’s Diplomacy’ (n 4).

[40] ‘Shipping on Northern Sea Route up 40% | The Independent Barents Observer’ <https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic-industry-and-energy/2019/10/shipping-northern-sea-route-40> accessed 5 April 2020.

[41] NSF Abdul Rahman, AH Saharuddin and R Rasdi, ‘Effect of the Northern Sea Route Opening to the Shipping Activities at Malacca Straits’ (2014) 1 International Journal of e-Navigation and Maritime Economy 85 <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405535214000096> accessed 14 September 2019.

[42] ‘Singapore Economy’ (n 21).

[43] Published at: Apr 16 2020-09:17 / Updated at: Apr 16 2020-09:17 From Malte Humpert, ‘Construction of Novatek’s Arctic LNG 2 Project Ahead of Schedule’ <https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/construction-novateks-arctic-lng-2-project-ahead-schedule> accessed 14 May 2020.

[44] MarketScreener, ‘Samsung Heavy Industries : Zvezda Shipbuilding Complex and Samsung Heavy Industries Sign Contract for Arctic LNG 2 Project Gas Carriers Design | MarketScreener’ <https://www.marketscreener.com/SAMSUNG-HEAVY-INDUSTRIES-6491583/news/Samsung-Heavy-Industries-Zvezda-Shipbuilding-Complex-and-Samsung-Heavy-Industries-Sign-Contract-fo-29163839/> accessed 31 March 2020.

[45] ‘Arctic Relevant Policies – Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network’ <https://arcticiceland.is/en/the-arctic/arctic-relevant-policies#japan> accessed 14 May 2020.

[46] ‘Observers’ (Arctic Council) <https://arctic-council.org/en/about/observers/> accessed 14 May 2020.

[47] USGS, ‘Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal: Estimates of Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle’ <https://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3049/fs2008-3049.pdf>.

[48] Published at: Dec 05 2019-08:20 / Updated at: Jan 20 2020-23:55 From Malte Humpert, ‘Greenland’s Kangerlussuaq Airport to Close For Major Commercial Traffic in 2024 Due to Climate Change’ <https://www.highnorthnews.com/en/greenlands-kangerlussuaq-airport-close-major-commercial-traffic-2024-due-climate-change> accessed 6 May 2020.

[49] Richard Luedde-Neurath, ‘State Intervention and Export-Oriented Development in South Korea’ in Gordon White (ed), Developmental States in East Asia (Palgrave Macmillan UK 1988) <http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-1-349-19195-6_3> accessed 14 May 2020.

[50] ‘South Korea to Combine World’s Two Biggest Shipbuilders in $2 Billion Deal’ Reuters (31 January 2019) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-daewoo-s-m-m-a-hyundaiheavyinds-idUSKCN1PO17K> accessed 14 May 2020.

[51] William KM Lee, ‘Economic Growth, Government Intervention, and Ideology in Singapore’ (1996) 12 New Global Development 27 <http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17486839608412592> accessed 14 May 2020.

[52] ‘American Flags in the Barents Sea Is “the New Normal,” Says Defence Analyst’ (The Independent Barents Observer) <https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/security/2020/05/american-flags-new-normal-barents-sea-says-defence-analyst> accessed 14 May 2020.

[53] Gunnar Rekvig, ‘The Legacy of the Nordic Peace and Cold War Trust-Building in the North Atlantic’ (Háskólinn á Akureyri) <https://www.unak.is/is/samfelagid/vidburdir/gunnar-rekvig-a-felagsvisindatorgi> accessed 14 May 2020.

[54] ‘Russia Says New Weapon Blew Up in Nuclear Accident Last Week’ Bloomberg.com (12 August 2019) <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-12/russian-says-small-nuclear-reactor-blew-up-in-deadly-accident> accessed 14 May 2020.

[55] ‘How the Pentagon Countered China’s Designs on Greenland – WSJ’ <https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-the-pentagon-countered-chinas-designs-on-greenland-11549812296> accessed 13 April 2020.

[56] Barbara Padrtova, ‘Russian Military Build-up in the Arctic: Strategic Shift in the Balance of Power or Bellicose Rhetoric Only?’ <https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2014/2014-scholarly-papers/91-russian-military-build-up-in-the-arctic-strategic-shift-in-the-balance-of-power-of-bellicose-rhetoric-only> accessed 14 May 2020.

[57] ‘The Increasing Security Focus in China’s Arctic Policy’ (The Arctic Institute, 16 July 2019) <https://www.thearcticinstitute.org/increasing-security-focus-china-arctic-policy/> accessed 14 May 2020.

[58] ‘Moscow Sends Signal It Might Raise Stakes in Svalbard Waters | The Independent Barents Observer’ <https://thebarentsobserver.com/en/arctic/2020/04/moscow-sends-signal-it-might-raise-stakes-svalbard-waters> accessed 14 May 2020.